In This Program

- The Concert

- At a Glance

- Program Notes

- About the Artists

- San Francisco Symphony Chorus

- San Francisco Girls’ Chorus

- About San Francisco Symphony

The Concert

Thursday, January 16, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, January 18, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, January 19, 2025, at 2:00pm

David Robertson conducting

Charles Ives

The Unanswered Question (1906)

John Adams

After the Fall (2024)

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Víkingur Ólafsson piano

Intermission

Carl Orff

Carmina burana (1936)

Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World)

O Fortuna–Fortune plango vulnera

I. Primo Vere (In Spring)

Veris leta facies–Omnia Sol temperat–Ecce gratum

Uf Dem Anger (In the Meadow)

Dance–Floret silva–Chramer, gip die varwe mir–Reie–Swaz hie gat umbe–Were diu werlt alle min

II. In Taberna (In the Tavern)

Estuans interius–Olim lacus colueram–Ego sum abbas–

In taberna quando sumus

III. Cour d’amours (Court of Love)

Amor volat undique–Dies, nox et omnia–Stetit puella–Circa mea pectora–Si puer cum puellula–Veni, veni, venias–In trutina–Tempus est iocundum–Dulcissime

Blanziflor et Helena

Ave formosissima

Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi

O Fortuna

Susanna Phillips soprano

Arnold Livingston Geis tenor

Will Liverman baritone

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

San Francisco Girls Chorus

Valérie Sainte-Agathe artistic director

Lead support for the San Francisco Symphony Chorus this season is provided through a visionary gift from an anonymous donor.

David Robertson’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

The commissioning of John Adams’s Piano Concerto for Víkingur Ólafsson is supported by the Ralph I. Dorfman Commissioning Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by Claudine Cheng.

Susanna Phillips’s performance is made possible by the Mrs. George J. Otto Memorial Vocalist Fund.

Supporting the SF Symphony Chorus

Our artists are the lifeblood of our mission to bring meaningful, high-caliber musical experiences to our community. Philanthropic support is essential to this work.

We are deeply grateful for an extraordinary $4 million gift from an anonymous donor, providing vital annual operating support to the Chorus and establishing a dedicated endowment fund to ensure the San Francisco Symphony Chorus’s longevity.

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus Fund enables additional supporters to contribute and amplify its impact. Patrons interested in making a donation towards the San Francisco Symphony Chorus Fund are encouraged to contact us at support@sfsymphony.org.

We hope this donor’s impactful generosity inspires others to help sustain excellent choral programming and strengthen the San Francisco Symphony Chorus for generations.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Next, Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson premieres John Adams’s newest piano concerto, After the Fall. It is the Bay Area composer’s ninth work commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony and incorporates part of J.S. Bach’s C-minor Prelude from Book I of The Well-Tempered Clavier in its culmination. The title refers both to the season and to an artistic fall from Paradise.

Carl Orff’s pseudo-medieval cantata Carmina burana completes the program. No one who has heard the opening movement “O Fortuna” even once, whether live or on a film soundtrack, could question the eternal-earworm status of this banger of all choral bangers. But does it remain politically and aesthetically controversial despite, or because of, its rah-rah popularity?

The Unanswered Question

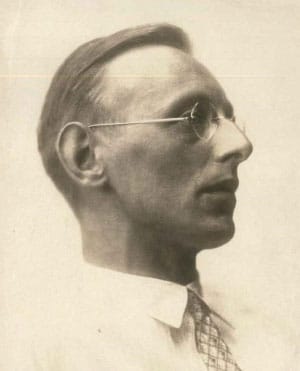

Charles Ives

Born: October 20, 1874, in Danbury, Connecticut

Died: May 19, 1954, in New York

Work Composed: 1906 (rev. 1941)

SF Symphony Performances: First—May 1960. Enrique Jordá conducted. Most recent—June 2017. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 4 flutes, trumpet, and strings

Duration: About 6 minutes

Charles Ives went to college at Yale where he managed to graduate in 1898 after holding on with a D-plus grade-point average. Following graduation, he sensibly took a position with an insurance firm. He proved exceptionally adept in that field, and in 1906 he began planning the creation of his own company, the eventual Ives & Myrick, in New York City. In 1905 he had entered into a courtship with Harmony Twitchell, “the most beautiful girl in Hartford,” whom he would marry in 1908. At about this time he also let loose a succession of wildly adventurous compositions, the most enduring of which is The Unanswered Question.

Throughout his career, Ives jotted memos to himself to capture thoughts on his music, his intended projects, his experiences, and a plethora of other topics. Here’s what Ives jotted down at some point about The Unanswered Question:

Around this time, running from say 1906. . . up to about 1912–14 or so, things like. . . The Unanswered Question, etc. were made. Some of them were played—or better tried out—usually ending in a fight or hiss. . . . I must say that many of those things were started as kinds [of] studies, or rather trying out sounds, beats, etc., usually by what is called politely “improvisations on the keyboard”—what classmates in the flat called “resident disturbances.”

In a list of works that he included with the memos, Ives identified the piece as The Unanswered Question, A Cosmic Landscape, and he noted that he had written it “some time before June, 1908.” However, Ives’s sketch for the piece bears an address that was only valid through 1906; this, along with other biographical data, helps date the genesis of the piece more precisely to July 1906.

In its first incarnation, The Unanswered Question took the form of a one-page sketch. Nonetheless, its essential character was already well in place: three distinct sonic levels, each with its own unvarying instrumentation and melodic style, overlapping in a way that is both loosely controlled and fraught with programmatic implications. In the mid-1930s, Ives took up his early sketch and fashioned it into completed form, in which guise it was published (without authorization) in the October 1941 edition of the Boletín Latino-Americano de Música, under the title La Pregunta Incontestada. In 1953 it was finally released in a more broadly available format by Southern Music Publishing Co. In any case, it’s surprising to think that this work occupies only five far-from-dense pages of full orchestral score.

The Music

In an extensive prose forward to his published score, Ives described:

The strings play ppp [extremely quiet] throughout with no change in tempo. They are to represent “The Silences of the Druids—Who Know, See, and Hear Nothing.” The trumpet intones “The Perennial Question of Existence,” and states it in the same tone of voice each time. But the hunt for “The Invisible Answer” undertaken by the flutes and other human beings, becomes gradually more active, faster and louder through an animando to a con fuoco. . . . “The Fighting Answers,” as the time goes on, and after a “secret conference,” seem to realize a futility, and begin to mock “The Question”—the strife is over for the moment. After they disappear, “The Question” is asked for the last time, and “The Silences” are heard beyond in “Undisturbed Solitude.”

—James M. Keller

After the Fall

John Adams

Born: February 15, 1947, in Worcester, Massachusetts

Work Composed: 2023–24

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: solo piano, 3 flutes (2nd doubling alto flute and 3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion (tam-tam, bass drum, vibraphone, chimes, and 8 tuned gongs), 2 harps, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 27 minutes

With its inherent malleability, the concerto format has proved especially attractive to John Adams. Concertos figure conspicuously among his orchestral compositions, each one involving a unique approach to the genre’s fundamental scenario of a virtuoso protagonist.

Even Adams’s concertos for the same instrument differ strikingly one from the other. After the Fall is the composer’s third full-scale concerto for solo piano, following Century Rolls (1996), which he wrote for Emanuel Ax, and Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? (2018), a concerto premiered by Yuja Wang. It also marks his ninth work to be commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony (the first, Harmonium, goes back to 1981).

By taking into account the personalities and specific strengths of the keyboard virtuosos for whom each piece was originally tailored, Adams demonstrates a compositional virtuosity all his own. Víkingur Ólafsson, to whom After the Fall is dedicated, has become an acclaimed interpreter of J.S. Bach, and Adams alludes to this extraordinary Bachian affinity in his score.

Ólafsson first made a powerful impression on Adams when he played Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? across Europe with the composer conducting. He also introduced the concerto to San Francisco Symphony audiences in 2022. Ólafsson’s deep and thorough knowledge of his music additionally impressed Adams: “He genuinely loves my music and knows all of it, not just my concertos.” When writing for a particular performer, he adds, “that makes a difference.”

Adams in turn became a fan of Ólafsson. “The extraordinary thing about him is that he has such a wide bandwidth of expressive possibility,” the composer says. “His Rameau and Bach and Mozart have incredible delicacy, and at the same time he can make the piano sound huge without banging it. I tried to incorporate that awareness into After the Fall.”

The title of the new concerto is a multi-layered pun. Adams recalls hearing the piano concerto No Such Spring by his son, Samuel Carl Adams (also an SF Symphony commission), which was premiered by the pianist Conor Hanick and Esa-Pekka Salonen in early 2023. “I was so overwhelmed by it that I really didn’t think I could ever write another piano concerto,” Adams recalls. “So the title is partly a tip of the hat to Sam’s piece: there is no such spring after the fall.”

The double entendre of “fall”—as both the season and the “loss of Paradise”—led Adams to think of the role Pierre Boulez (1925–2016) once played in attempting to dictate the future of contemporary music. Boulez declared his dystopian view that “the era of avant-gardes and exploration being definitely over, what follows is the era of perpetual return, consolidation, citation. . . An ideal or imaginary library provides us with a plethora of models, endless choices and means of exploitation.”

From Boulez’s strict modernist perspective, Adams says, the fall from grace for the present-day artist “is like some Miltonian catastrophe where the nobility of the avant-garde posture is surrendered in favor of some sort of sentimental clinging to archetypes from the past, to a retreat into nostalgia and quotation.” While the ideal of the avant-garde was “to push the limit on everything, whether in terms of comprehensibility, of loudness and softness, or of length or density,” Adams points out that he has long felt, when composing, that “there is an aspect in which so many of the fundamental tools of music—harmony, rhythm, timbre, etc.—have in a certain sense already been discovered. What to me is meaningful and touches people is music that does have roots in the past, but that sees the musical experience from a different point of view.”

After the Fall, like all of Adams’s music, embraces the very things Boulez pronounced to be signs of the fall: “perpetual return, consolidation, citation.” But risks must still be taken—all the more so. In the culminating section of After the Fall, Adams stages the infiltration of the C-minor Prelude from Book I of Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier. The composer wryly notes that while at work on the piece last season, Ólafsson was engaged in an international tour comprising 88 performances of the Goldberg Variations: “Something of Bach was bound to leak into my piece, I guess.”

The Music

Adams embeds the outline of an archetypal three-movement design within a single large structure. Instead of breaks between sections, they meld together subtly. After the Fall opens in a dreamy trance of densely textured strings spread over octaves, with harps, celesta, vibraphone, and tuned gongs producing delicate bell-like sounds.

The solo piano enters almost at once, reshaping the mysterious chord sequence laid out here into brittle, erratic rhythmic shapes. The soloist remains active throughout, with few passages of respite. The tempo eventually slows as a descending theme is presented, like an angular falling gymnopédie. After an agitated central episode, the falling music returns, varied with ever-more-elaborate rhythmic subdivisions and textural accents.

About two-thirds of the way through the concerto, a recurring quintuplet pattern in the woodwinds remolds itself into the 16th-note perpetuum mobile phrases of the Bach prelude. The solo piano placidly takes up the thread to traverse a new harmonic labyrinth. Rather than a straightforward quotation, Adams makes the familiar strains feel like a destination that has always been there, buried in the layers of the music. At the same time, its persistence ushers in a sense of enigma.

Originally, Adams planned a “more glamorous ending,” but he decided that “it just didn’t feel right. The ending of a piece is so important, because, in a sense, you’re really saying what it was about.” The tempo accelerates in a dramatically agitated coda, but the music suddenly wanes, leaving a lone harp to pluck out a quiet, bell-like alarm against sustained string chords—an unresolved echo of the beginning.

—Thomas May

Carmina burana

Carl Orff

Born: July 10, 1895, in Munich

Died: March 29, 1982, in Munich

Work Composed: 1935–36

SF Symphony Performances: First—August 1978. John Nelson conducted with Kathleen Battle, William Harness, and Brent Ellis as soloists and the SF Symphony Chorus. Most recent—June 2019. Christian Reif conducted with Nikki Einfeld, Nicholas Phan, and Hadleigh Adams as soloists and the SF Symphony Chorus.

(In 2022 and 2024 Jenny Wong directed the SF Symphony Chorus in the Wilhelm Killmayer arrangement for 2 pianos and percussion.)

Instrumentation: 3 soloists (soprano, tenor, and baritone), chorus, children’s chorus, 3 flutes (2nd and 3rd doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (3rd doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (2nd doubling bass clarinet and 3rd doubling E-flat clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani (2 players), percussion (antique cymbals, bass drum, castanets, chimes, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, ratchet, sleigh bells, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, tubular bells, and xylophone), 2 pianos, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 60 minutes

If you are alive today, chances are you have been exposed to Carl Orff. Don’t recognize the name? Doesn’t matter. You probably had a grade-school music teacher who did. Maybe you attended an elementary school with a collection of Orff instruments: special xylophones and glockenspiels tuned to sound harmonious in untrained children’s hands. And maybe you learned about pitch and meter by playing Orff-prescribed games and using your body in motion to express these abstractions. All this was part of Orff’s pedagogical theory, which he called Schulwerk, and which remains influential today.

But even if you never took a music class, you can surely hum the main hook to Orff’s “O Fortuna” from Carmina burana. After the cantata’s successful premiere at the Frankfurt Opera on June 8, 1937, Orff issued the following instructions to his music publisher: “Everything I have written to date, and which you have, unfortunately, printed, can be destroyed. With Carmina burana, my collected works begin.”

The text—in Medieval Latin, Old French, and Middle-High German—comes from a 13th-century poetry collection by a motley assortment of itinerant monks and scholars. These stubbornly secular, often bawdy verses touch on the corruption of the clergy, the benefits of intoxication, the sorrow of love, the glories of nature, and the pitiless wheel of fortune that determines our destinies. Lost for centuries before being rediscovered at a Benedictine abbey near Munich, the collection was first published as a book in 1847. Orff selected two dozen poems from it to set to music. He went on to create a conceptual trilogy called Trionfi, including the subsequent cantatas Catulli Carmina (1943) and Trionfo di Afrodite (1951), but the two later installments never took off and are virtually unknown today.

The Backstory

Orff was brought up in a Bavarian military family, in a culture that understood itself to be the natural extension of both Athens and Rome, an aspirational lineage connecting the recently unified Germany with the ancient Greco-Roman world. Even as a young composer in the interwar period, as modernism triumphed across all artforms, Orff was a devoted antiquarian who preferred engaging with centuries-old literature. For musical enjoyment, he pored over the scores of J.S. Bach, Monteverdi, and other Baroque composers of choral music.

Orff remained in Germany during the rise of the Third Reich, and although he did not join the Nazi Party, he was a member of the Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Chamber of Music), a requirement for all active musicians. One Nazi critic condemned Carmina burana for its “jazzy atmosphere” and “incomprehensible” text, which were seen as reflecting the decadence of the Weimar Republic rather than the athleticism that the Nazis celebrated in their racist and revisionist interpretation of ancient history. That was the exception, however: in general, the Nazis loved Carmina burana and programmed it repeatedly.

The commentator Anne-Charlotte Rémond of France Musique recently wrote that if Orff’s music isn’t “Nazi art,” it’s art “made for Nazis.” For many that’s a distinction with no real difference. On the other hand, Alex Ross in the New Yorker quipped that Carmina’s enduring status in popular culture is “proof that it contains no diabolical message, indeed that it contains no message whatsoever.”

Perhaps the late musicologist Richard Taruskin had the most nuanced, yet ultimately damning take. He found Orff’s music—relentless rhythms, hammered-home melodies, crude harmonies—“obviously” suited to propaganda, citing “its ubiquitous employment for such purposes even today . . . in commercials for chocolate, beer and juvenile action heroes.” He concluded that, without questioning our right to perform and listen to it, “one may still regard his music as toxic, whether it does its animalizing work at Nazi rallies, in school auditoriums, at rock concerts, in films, in the soundtracks that accompany commercials, or in [the concert hall].”

Orff completed the denazification process in 1946 and an American officer rated him “Grey C, acceptable,” a designation intended for Germans who were “compromised by their actions during the Nazi period but not subscribers to Nazi doctrine.” It’s a situation similar to that of Richard Strauss, who actually headed the Reichsmusikkammer for a time, but was found “not incriminated” by the Allies. (Though his poet colleague Hermann Hesse was more equivocal: “We have no right to level accusations, yet we do have the right to distance ourselves from him.”) The special scrutiny of Carmina burana seems less motivated by politics and history than by an aesthetic—even moral—concern for its musical content. No other piece invites quite the same fist-pumping involvement from its listeners, something viewed dubiously in the classical tradition.

The Music

Orff’s score bears a lengthy Latin subtitle, which, in translation, reads: “Profane songs to be sung by soloists and chorus with an accompaniment of instruments and magic tableaux.” It comprises a brief prologue (Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi, or Fortune, Empress of the World) succeeded by three main sections demonstrating the forces of fate. The first section is in two parts: Primo Vere (In Spring) and Uf Dem Anger (In the Meadow). The second and third sections are, respectively, In taberna (In the Tavern) and Cours d’amours (The Court of Love). A chorus celebrates the lovers Blanziflor and Helena, and then Orff concludes with a reprise of his O Fortuna theme.

By turns crude and celestial, the songs reflect Orff’s passion for the plainchant of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. As anyone who has ever sung it will attest, some of it amounts to vocal-cord torture. The aria “Olim lacus colueram,” for instance, is sung almost entirely in falsetto, straining the solo tenor’s voice to the breaking point—which makes sense when you remember that the lines are sung from the perspective of a roasting swan. A wildly erotic passage in “Cours d’amour” forces the soprano soloist to reach into the upper limits of her range, creating an exquisite tension.

“In all my work,” Orff wrote, “my final concern is not with musical but with spiritual exposition.” This claim might seem at odds with the visceral, almost orgiastic sonic thrust of Carmina burana, but Orff, like the medieval poets who inspired him, saw the spiritual and the profane as different spokes of the same cosmic wheel.

—René Spencer Saller

Hear the San Francisco Symphony and Chorus’s Grammy Award–winning Carmina burana with Herbert Blomstedt (Decca, 1991) on all popular streaming services.

A version of this note originally appeared in the program book of the Dallas Symphony.

About the Artists

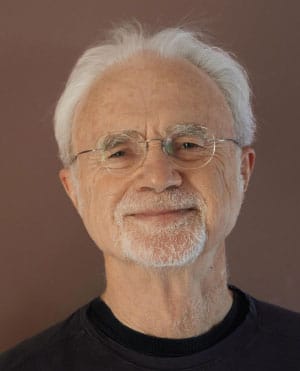

David Robertson

David Robertson—conductor, artist, composer, thinker, American musical visionary—occupies the most prominent podiums in orchestral music, new music, and opera. He is a champion of contemporary composers and an adventurous programmer. He has served in numerous artistic leadership positions, including chief conductor and artistic director of the Sydney Symphony; a transformative 13-year tenure as music director of the St. Louis Symphony; music director of the Orchestre National de Lyon; principal guest conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra; and, as a protégé of Pierre Boulez, music director of the Ensemble InterContemporain.

This season, Robertson celebrates the Boulez centennial with the New York Philharmonic, Juilliard Orchestra, Aspen Music Festival, and Lucerne Festival Contemporary Orchestra. He also conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Seattle Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Seoul Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, NDR Elbphilharmonie, and Bavarian Radio Orchestra. He leads European tours with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and Australian Youth Orchestra, and continues his three-year project as the inaugural creative partner of the Utah Symphony and Opera, where his guitar ensemble, Another Night on Earth, made its US debut. In previous seasons, he has appeared with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Vienna Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic, São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra, and many other major ensembles and festivals on five continents. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in January 1997.

Since his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1996, Robertson has conducted the 2019–20 season opening premiere production of Porgy and Bess, for which he shared a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. In 2022, he conducted the Met revival of the production, in addition to making his Rome Opera debut conducting Janáček’s Káťa Kabanová. Robertson is the director of conducting studies at the Juilliard School and serves on the Tianjin Juilliard Advisory Council. He is a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of France, and is the recipient of numerous artistic awards.

Víkingur Ólafsson

Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson has captured the public and critical imagination with profound musicianship and visionary programs. One of the most sought-after artists of today, Ólafsson’s recordings for Deutsche Grammophon have led to almost one billion streams and garnered numerous awards, including BBC Music Magazine Album of the Year and Opus Klassik Solo Recording of the Year, twice. Other notable honors include the Rolf Schock Music Prize, Gramophone’s Artist of the Year, Order of the Falcon (Iceland’s order of chivalry), as well as the Icelandic Export Award, given by the president of Iceland. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist in June 2022 performing John Adams’s Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?. He returns to the SF Symphony later this winter for a Great Performers Series duo recital with Yuja Wang (March 2).

Ólafsson devoted his entire 2023–24 season to a world tour of a single work: J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, performing it 88 times to great critical acclaim. This season sees Ólafsson as artist in residence with the Tonhalle Zurich and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, as well as “artist in focus” at Vienna Musikverein. He tours Europe with the Cleveland Orchestra, London Philharmonic, and Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra; performs with the Berlin Philharmonic at the BBC Proms; and returns to the New York Philharmonic. This spring, Ólafsson will perform the last three Beethoven piano sonatas on multiple dates across the United States and Europe.

Read more about Víkingur Ólafsson.

Susanna Phillips

Susanna Phillips sings this season with the Seattle Symphony, Musica Sacra, Oratorio Society of New York, and St. Louis Symphony. Her career highlights include numerous appearances at the Metropolitan Opera, where she recently made a role debut as Mimì in La bohème; leading roles with Boston Baroque; and appearances at Lyric Opera of Chicago, Cincinnati Opera, Dallas Opera, Minnesota Opera, Fort Worth Opera Festival, Boston Lyric Opera, Gran Teatro del Liceu, and Oper Frankfurt. In concert, she has collaborated with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Santa Fe Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Gulbenkian Orchestra, Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and her native Huntsville Symphony. An avid chamber music collaborator, she has sung alongside Eric Owens in a program co-curated by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for Washington Performing Arts.

Phillips is a winner of the Met’s Beverly Sills Artist Award; first prize and audience prize at Operalia; and top prizes from the American Opera Society Competition, the Musicians Club of Women in Chicago, and the Marilyn Horne Foundation Competition. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in December 2012.

Arnold Livingston Geis

This season, tenor Arnold Livingston Geis returns to the role of Josef Bader in Aaron Zigman’s Emigré with the Beijing Music Festival, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and Hong Kong Philharmonic. He also joins Opera Carolina as Rodolfo in La bohème, Cincinnati Opera as Motel in Fiddler on the Roof, Opera in the Heights for his role debut as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, and the Baltimore Symphony for Stravinsky’s Renard. Recent appearances include the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and LA Master Chorale. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Geis made his Lincoln Center debut creating the role of Mr. Marks in Ricky Ian Gordon’s Intimate Apparel and joined esperanza spalding as Agamemnon in her and Wayne Shorter’s opera Iphigenia. He recently joined Washington National Opera as Jonathan Dale in Silent Night, Gastone in La traviata, and Busdriver/New Preacher in the world premiere of Taking Up Serpents. He also sang Nikolaus Sprink in Silent Night with Glimmerglass Opera, Arnold Murray in The Life and Death(s) of Alan Turing with Chicago Opera Theater, and Tamino in The Magic Flute with Pacific Opera Project. He has sung on film and television soundtracks including Tom and Jerry, Family Guy, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Fifty Shades of Grey, Minions, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, and Disney’s live-action The Lion King.

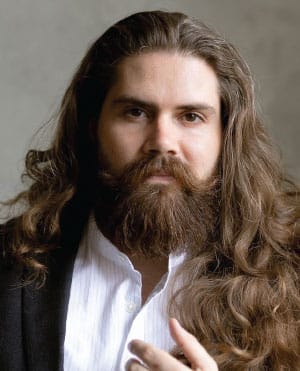

Will Liverman

Last summer, baritone Will Liverman appeared at the BBC Proms, Tanglewood, and Aspen Music Festival, and this season reprises the role of Papageno at the Metropolitan Opera, returns to Lyric Opera of Chicago as Marcello in La bohème, and joins Dutch National Opera as Ned in Peter Grimes. In June, he will make his house debut at San Francisco Opera, also portraying Marcello in La bohème. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

At the Met, Liverman starred last season in the title role of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, and in 2021 headlined Fire Shut Up in My Bones, which won the 2023 Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. In 2023, Lyric Opera of Chicago presented the world premiere of Liverman’s new opera, The Factotum, which he starred in and composed with DJ King Rico. Inspired by Rossini’s Barber of Seville, Liverman and Rico place the story in a present-day Black barbershop on Chicago’s South Side. Houston Grand Opera, Portland Opera, and Washington National Opera are all slated to produce The Factotum in future seasons.

Liverman’s recordings are available on Cedille Records, including Dreams of a New Day: Songs by Black Composers, which was nominated for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album at the Grammy Awards. His other accolades include a Sphinx MPower Artist Grant, Marian Anderson Vocal Award, and Richard Tucker Career Grant, among many others.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

Under Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance. She has also prepared choruses for the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and Music Academy of the West.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

Valérie Sainte-Agathe

San Francisco Girls Chorus artistic director Valérie Sainte-Agathe has prepared and conducted the San Francisco Girls Chorus since 2013, including performances with renowned ensembles throughout the United States and beyond. Through transformative choral music training, education, and performance, she empowers young women and champions the music of today throughout the choral world.

With SFGC, Sainte-Agathe has collaborated with San Francisco Opera, Chanticleer, Opera Parallèle, and folk singer Aoife O’Donovan. Sainte-Agathe joined Philharmonia Baroque as their chorale director in 2022 and was featured in the 2022 book Music Mavens: 15 Women of Note. Further career highlights include her Carnegie Hall and Barbican Centre debuts with the Philip Glass Ensemble, conducting with Michael Riesman in Glass’s Music with Changing Parts; conducting SFGC for the New York Philharmonic Biennial Festival at Lincoln Center; and collaborating with the Knights for the Shift Festival at the Kennedy Center.

San Francisco Girls Chorus

Established in 1978, the mission of the San Francisco Girls Chorus is to create outstanding performances featuring the unique and compelling sound of young women’s voices. Under artistic director Valérie Sainte-Agathe, the SFGMC performs choral masterworks from plainchant to the most challenging and nuanced contemporary works created expressly for them.

Each year, hundreds of singers from 45 Bay Area cities, ranging in age from 4–18, participate in the SFGC’s programs. The chorus has won five Grammy Awards, four ASCAP/Chorus America Awards for Adventurous Programming, and was the first youth chorus to receive Chorus America’s Margaret Hillis Achievement Award for Choral Excellence.

Supertitles: Ron Valentino

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

SOPRANOS

Elaine Abigail

Sylvia V. Baba

Alexis Wong Baird

Morgan Balfour*

Arlene Boyd

Olivia T. Brown

Helen J. Burns

Laura Canavan

Rebecca Capriulo

Sara Chalk

Phoebe Chee*

Francielle De Barros

Lauren Diez

Andrea Drummond

Tonia D’Amelio*

Elizabeth Emigh

Amy Foote*

Cara Gabrielson*

Tiffany Gao

Susanna Gilbert

Julia Hall

Ashley Hecht

Elizabeth Heckmann

Betsy Johnsmiller

Kate Juliana

Anna Keyta*

Jocelyn Queen Lambert

Becky Lau

Kyounghee Lee

Ellen Leslie*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Laura Stanfield Prichard

Bethany R. Procopio

Shroothi P. Ramesh

Hallie Randel

Rebecca Shipan

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Sarah Vig

Lauren Wilbanks

ALTOS

Carolyn Alexander

Terry A. Alvord*

Christina E. F. Barbaro

Melissa Butcher

Celeste Camarena

Enrica Casucci

Carol Copperud

Nicole Daamen

Corty Fengler

Stacey L. Helley

Kelsey M. Ishimatsu Jacobson

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen Josaitis

Gretchen Klein

Donna Kulkarni

Joyce Lin-Conrad

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Kimberly J. Orbik

Lindsay Marie Rader

Leandra Ramm*

Linda J. Randall

Meredith Riekse

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Kathryn Schumacher

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Sandy Sellin

Dr. Meghan Spyker*

Kyle S. Tingzon*

Mayo Tsuzuki

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

Hannah J. Wolf

TENORS

Paul Angelo

Alexander P. Bonner

Todd Bradley

Seth Brenzel*

Dean Christman

Scott Dickerman

Thomas L. Ellison

Sam Faustine*

Patrick Fu

Kevin Gibbs*

Kevin Gino*

Edward Im

Alec Jeong

Drew Kravin

James Lee

Benjamin Liupaogo*

Benjamin S. Lorenzoni

Joachim Luis*

Monty M. Maisano

Andrew P. McIver

Jack O'Reilly

Darita Seth*

Tetsuya Taura

John A. Vlahides

Jack Wilkins*

Weichen Winston Yin

John Paul Young

Jakob Zwiener

BASSES

Simon Barrad*

Josh Bozich

Sean Brooks

Phil Buonadonna

Robert Calvert

Sean Casey

Adam Cole*

Noam Cook

James Radcliffe Cowing III

Malcolm Gaines

Rick Galbreath

Richard M. Glendening

Harlan J. Hays*

Bradley A. Irving

Roderick Lowe

Tim Marson

Clayton Moser*

Case Nafziger

Julian Nesbitt

Chengrui Pan

Bradley C. Parese

Jess Green Perry

Michael Prichard

Mark E. Rubin

Chung-Wai Soong*

Storm K. Staley

Michael Taylor*

Connor Tench

David Varnum*

Julia Vetter

Nick Volkert*

Jenny Wong

Chorus Director

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist

* Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists

San Francisco Girls’ Chorus

Premier Ensemble

Ayve Algazi

Meher Arvind

Georgia Madland

Sofía Bourgon-Trujillo

Avery Brandstetter

Gloria Cebrian

Anushka Chandran

Ella Cody

Maya Cody

Cate Cross

Samsara Zofia Dluzak

Sadie Dobbs

Lillian Escher

Ariana Frey

Sofia Fung-Lee

Leena Heck

Julia Howe

Sofia Jun

Addison Li

Jessie Li

Sierra Valencia Lyon

Gitanjali Menon

Zara Nelson

Lily Grace Normanly

Genevieve Ooi

Mackenzie Pederson

Shayna Phillips

Wilhelmina Naumann Ratto

Elizabeth Rogers

Vianza Felisa Ruelos

Carissa Satuito

Sophia Shiller

Paloma Anais Siliezar

Vibhu Singh

Leonora Steward

Sophia Stolte

Calista Stone

Madeline Swain

Shiva Swaminathan Strickland

Anna Tanner

Shunnisha Tate

Anayah Tin

Kiyomi Treanor

Sara Wolfe

Violet Wolfe

Ellie Jung Si Wong

Grace Zhao

Valérie Sainte-Agathe,

Artistic Director