In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, December 1, 2024, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano

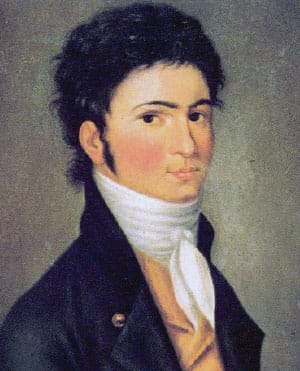

Ludwig van Beethoven

Violin Sonata No. 1 in D major, Opus 12, no.1 (ca. 1798)

Allegro con brio

Tema con Variazioni–Andante con moto

Rondo–Allegro

Cello Sonata No. 1 in F major, Opus 5, no.1 (1796)

Adagio sostenuto–Allegro

Allegro vivace

Intermission

Piano Trio in E-flat major, Opus 70, no.2 (1808)

Poco sostenuto–Allegro ma non troppo

Allegretto

Allegretto ma non troppo

Finale: Allegro

This series showcases the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin on loan to Alexander Barantschik and the San Francisco Symphony from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Program Notes

Violin Sonata No. 1 in D major, Opus 12, no.1

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1798

Ludwig van Beethoven studied the violin as a young man in Bonn and spent a stint as an orchestral violist before moving to Vienna to seek his fortune as a pianist and composer. In his diary for the year 1794, he wrote of meeting three times a week with Schuppanzigh, quite possibly referring to lessons with Ignaz Schuppanzigh, the violinist who would champion many of his compositions, including the groundbreaking string quartets. Even if he didn’t study violin with Schuppanzigh, he almost certainly did with Wenzel Krumpholz, who had been appointed violinist with the Vienna court orchestra following a period of service under Haydn at the Esterházy court. Beethoven was also active composing music with violin during those years, including an incomplete violin concerto in the early 1790s, two single-movement romances for violin and orchestra around the turn of the century, and many chamber pieces; by the time he got around to writing his famous D-major Violin Concerto, in 1806, he had completed all but the last of his 10 violin sonatas. Beethoven knew his way around a violin almost as well as he knew his way around a piano, a fact that is most happily put on display in his violin sonatas.

Typical of Classical violin sonatas, Beethoven identified his first set of three (Opus 12) as being written “for the Harpsichord or the Pianoforte with Violin.” In many earlier sonatas, the violin often did play “second fiddle” to the keyboard instrument; indeed, many composers designed their sonatas so that the violin could be omitted with no deleterious effect. But with Beethoven that designation is little more than a remnant: in each of the three Opus 12 sonatas we find true dialogue between the violin and the piano. That surely characterizes the opening movement of the D-major sonata, where the conversation sometimes even grows to resemble confrontation, so strongly does Beethoven etch the dramatic roles his two protagonists play.

Of Beethoven’s first set of sonatas, this is the only one to present a theme with variations as its second movement. It is a straightforward movement in which the violin and the piano embellish the simple, folk-like melody—though not at the same time, carefully keeping out of each other’s way when it comes to elaborations. The finale is a buoyant rondo: but for a touch of syncopation in the principal theme one might imagine that Beethoven had lifted the melody from Mozart.

Antonio Salieri, the rather conservative imperial kapellmeister of Vienna to whom Beethoven had turned for coaching in vocal composition, received the dedication of the Opus 12 sonatas when they were published, and he may well have raised an eyebrow at some of their more daring passages. The critic of Leipzig’s Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung certainly did. In June 1799 he found, “after having looked through these strange sonatas, overladen with difficulties, that after diligent and strenuous labor he [the critic] felt like a man who had hoped to make a promenade with a genial friend through a tempting forest and found himself barred every minute by inimical barriers, returning at last exhausted and without having had any pleasure.” Perhaps such music is not for everybody, he suggests. “There are always many who love difficulties in invention and composition, what we might call perversities, and if they play these Sonatas with great precision they may derive delight in the music as well as an agreeable feeling of satisfaction. If Herr v. B. wished to deny himself a bit more and follow the course of nature he might, with his talent and industry, do a great deal for an instrument which he seems to have so wonderfully under his control.” As it happened, Herr v. B did not so wish, and his Opus 12 sonatas stand not only as beacons of late Classicism but also as harbingers of the “course of nature” to come.

Cello Sonata No. 1 in F major, Opus 5, no.1

Ludwig van Beethoven

Work Composed: 1796

The eight works for cello and piano by Ludwig van Beethoven—five sonatas, three sets of variations—add up to an unusually interesting volume of chamber music, remarkable not only for the quality and variety of the individual pieces but also for how they illuminate the distance the composer traveled in the 19 years that separate the first works from the last. His two sonatas (Opus 5) and his Variations on a Theme from Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus date from 1796, just when his career as a composer was beginning to take off. In fact, he was not yet earning his living as a full-time composer, and wrote—or at least unveiled—the first two sonatas in Berlin, while touring there as a pianist. Two further sets of variations, both on themes from Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte, followed shortly, the “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” Variations sometime between 1796 and 1798, and the “Bei Männern” Variations in 1801, reaching the era of Beethoven’s first two symphonies and the culmination of what is widely considered his early style. Three further works for cello and piano would follow. His A-major sonata (Opus 69), written in 1807–08, is one of the crowning glories of his middle period; and his final two sonatas (Opus 102) were composed in 1815, just as he was entering his visionary late period.

When the two Opus 5 sonatas were published, in February 1797, they bore a dedication to Friedrich Wilhelm II, king of Prussia, a music-loving, cello-playing monarch who was also the dedicatee of Haydn’s six Prussian Quartets (Opus 50) and Mozart’s three Prussian Quartets (K. 575, 589, and 590). Beethoven played for him several times during his 1796 visit to Berlin and was the pianist when this piece was premiered at court. The composer’s secretary Ferdinand Ries wrote in his Biographical Reminiscences of Beethoven (1838) that the cellist on that occasion was “Duport, first cellist of the king.” There were two Duport cellists at the court—brothers, both born in Paris. Friedrich Wilhelm II appointed the older, Jean-Pierre, as his orchestra’s principal cellist in 1773 and elevated him to become intendant (director of entertainment) in 1787, at which point the younger brother, Jean-Louis, became principal cellist. Both remained until 1806, when they returned to Paris. It is assumed that Beethoven’s cellist was Jean-Louis, who was the first cellist at that time. The king apparently liked what he heard, and Ries reported: “On his departure he received a gold snuff-box filled with louis d’ors. Beethoven declared with pride that it was not an ordinary snuff-box, but one that it might have been customary to give to an ambassador.”

The F-major cello sonata unrolls over two movements. That strikes one as surprisingly telescoped in comparison to normal sonatas of the day, but in fact the work’s slow introduction (Adagio sostenuto) is so substantial as to suggest a movement in its right. That introduction has an improvisatory quality, with themes touched upon but not really developed. When the music breaks into Allegro for the main part of the movement, the theme is entrusted to the piano and is then handed off to the cello. This begins as very Mozartian music, but Beethoven puts his personal stamp on it soon enough thanks to his signature punchiness and his penchant for developing his material at length. Near the movement’s end he writes out a cadenza for both instruments; it wends its way into a few measures of enervated Adagio and then on to a Presto conclusion. The second (and concluding) movement is a playful rondo. It keeps up its unflagging energy nearly without a break until, after five minutes or so, the mechanism seems to wind down in a huge ritardando. It’s a feint, and it makes the final burst of energy seem all the more explosive.

Piano Trio in E-flat major, Opus 70, no.2

Ludwig van Beethoven

Work Composed: 1808

In late 1808, the Vienna home of Countess Anna Maria von Erdödy resounded with the first performance of Beethoven’s two Opus 70 piano trios, which were dedicated to her when they were published in the summer of 1809. An accomplished pianist, she was a devoted friend and supportive patron of Beethoven’s at that time—he is said to have referred to her as his “Father Confessor”—and she included his music in her frequent musical soirées, where Beethoven himself sometimes performed. She achieved further immortality in 1815 as the dedicatee of Beethoven’s Opus 102 Cello Sonatas, which were premiered at her country house outside Vienna.

The first of the Opus 70 trios is the more famous: the Ghost Trio. The second is overwhelmingly genial and warm-hearted: a yin-and-yang dyad. At least on an emotional plane, Opus 70, no.2, seems more connected to the patrician Archduke Trio, which lay two years in the future, or, for that matter, to the style of the composer’s younger years, although the harmonic subtlety of this trio surpasses anything Beethoven achieved a decade earlier. This work entirely lacks a slow movement, which would have been a natural repository for deep thoughts, and the whole four-movement span remains within the bounds of relatively moderate tempos. An elegant, if not entirely unruffled, introduction launches the piece. Its carefully plotted, step-wise lines in slow but flowing counterpoint, canonic at the outset, invest this opening with a searching quality. This leads to the main section of the movement, a lyrical effusion with an aristocratic bearing. Just before the end, the composer brings back a reminiscence of the “searching music” of the introduction, this time with the scoring altered.

Both of the middle movements are Allegrettos but they have quite different characters. The second movement sounds resolutely old-fashioned, beginning with a modern take on a Baroque gavotte. Major-key variations on this alternate with minor-key sections based on a more vehement element. The marking Allegretto already represents a moderate tempo: adding ma non troppo (“but not too much”), as Beethoven does in the third movement, seems not particularly helpful: does he mean that players should shade the Allegretto to the fast or the slow side? Perhaps the former, as this spot in a composition would most characteristically have been the place for a triple-meter minuet—or, at this point in Beethoven’s career, a scherzo—and the movement is cast in the meter and structure of those forms, though with the main episode and the “trio” repeated, extending the movement from the usual A-B-A of a scherzo to a five-section A-B-A-B-A structure. But at heart we have no scherzo here. The spirit is Apollonian rather than Bacchic, and the phrases are studiously symmetrical, again displaying something of an antique character.

With the finale, we finally have a full-fledged fast movement. And yet, hardly does it get started with energetic, ascending piano flourishes than the strings pull on the reins, an interruption Beethoven will continue to try out later. In general, though, the movement proceeds apace as it works through its episodes. “It is a continuous, ever mounting bustle and commotion—ideas, images chase by in a restless flight, and sparkle and disappear like flashes of lightning—it is a free play of the most highly aroused imagination”: so wrote E.T.A. Hoffmann in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1813. Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny maintained that in the G-major section in the middle of this finale Beethoven drew on Croatian melodies that were popular in Hungary, which would have been an appropriate nod from the composer to Countess Erdödy, who belonged to a family of Hungarian aristocrats.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri “del Gesù” violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

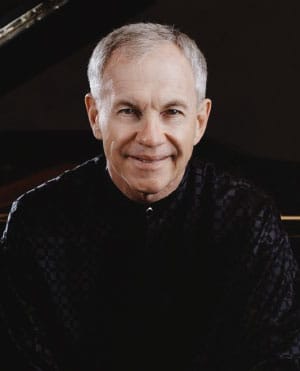

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of last season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.