In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, March 23, 2025, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Trio in B-flat major, K.502 (1786)

Allegro

Larghetto

Allegretto

Cécile Chaminade

Automne, Étude de concert, Opus 35, no.2 (1886)

Thème varié, Opus 89 (1898)

Anton Nel piano

Intermission

Johannes Brahms

Piano Trio No. 3 in C minor, Opus 101 (1886)

Allegro energico

Presto non assai

Andante grazioso

Allegro molto

The Chamber Music Series at the Legion of Honor is supported by Ann Paras.

This series showcases the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin on loan to Alexander Barantschik and the San Francisco Symphony from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Program Notes

Piano Trio in B-flat major, K.502

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1786

In the early piano trios of Haydn (appearing in the 1760s and ’70s) and Mozart, little in the writing distinguishes the pieces from sonatas for violin and piano, since the cello mostly doubles the bass line played by the pianist’s left hand. But by the mid-1780s, Haydn first, and then Mozart, began endowing the medium with greater equality of parts. Mozart returned to the genre in 1786 to produce two piano trios, completed respectively on July 8 (in G major, K.496), and November 18 (in B-flat major, K.502), the latter being the work played here.

The titles attached to the 1786 trios suggest how the medium was in a moment of flux. On the title page of his manuscript for K.496, Mozart labels the work a “Sonata,” implying the primacy of the violin and piano parts and the secondary nature of the cello. Yet when he finished composing the piece and entered it into the catalogue of his works, he called it instead a Terzett (Trio), which is also the name he attached to K.502 on both its manuscript title page and in his catalogue. The two pieces were published promptly by Franz Anton Hoffmeister, who issued both as Terzette.

The new spirit breathed into keyboard trios in the 1780s corresponded with the supplanting of the harpsichord by the fortepiano and by important technical advances in Viennese piano-building. As an acclaimed keyboard virtuoso, Mozart was exquisitely attuned to the newly developed subtleties of these instruments and made the most of them.

The piano occupies a position of first among equals in K.502, and for considerable expanses one could imagine this work being easily rendered as a concerto or even a solo sonata. The opening movement is tightly constructed, with everything being based on a single melody—a Haydnesque trait but rarely a Mozartian one. It’s a lighthearted, rather nonchalant tune. As the movement unrolls, we are surprised to find that the theme offers as much opportunity as it does for harmonic and contrapuntal elaboration.

The Larghetto is structured as a relaxed rondo. The commentator Arthur Cohn seized on its subdued nature when he wrote, “The slow movement is in major, but is itching to go into minor, not tonally, but with the melos itself.” In the finale we find Mozart working out his material through a sonata-rondo form, in which the principal theme not only recurs but is also subjected to exploration through a finely wrought development section—again with an unassuming theme harboring more possibilities for elaboration than we might have expected at first hearing. The second and third movements of this trio seem not far removed from the piano concertos Mozart was writing at about that time, not only in their formal plans and the flavor of their melodies but also in the way which the principal themes are adorned at their repetitions, not merely in the spirit of forthright decoration but as a means of expanding the emotional terrain.

—James M. Keller

Automne, Étude de concert, Opus 35, no.2

Thème varié, Opus 89

Cécile Chaminade

Born: August 8, 1857, in Paris

Died: April 13, 1944, in Monte Carlo, Monaco

Works Composed: Automne—1886. Thème varié—1898.

The Chaminade Music Club of Yonkers, New York, was founded in 1895 by music lovers “for the sole purpose of participating in piano and voice recitals to entertain themselves and others.” Still active today, the group was one of dozens formed in the late 19th century in honor of French composer Cécile Chaminade, whose music was a fixture at such gatherings. Chaminade’s heyday coincided with the Belle Époque and the flourishing of Paris’s salon scene, where her elegantly crafted piano miniatures found a natural home.

As a young musician, Chaminade was prohibited by her father from entering the Paris Conservatory, so she trained privately with esteemed composers such as Benjamin Godard. While she composed several symphonic works, including the Concertstück for piano and orchestra and a popular concertino for flute, she ultimately focused on the smaller-scale pieces that became her livelihood. She published nearly 400 works—primarily songs and piano pieces—building a devoted following through sheet-music sales, piano recitals, and piano roll recordings. This was a savvy strategy for a composer navigating the barriers of Paris’s musical establishment, where tradition and connections often dictated success.

Chaminade’s popularity extended beyond France to England and the United States, where she toured to great success in 1908, including a sold-out engagement at Carnegie Hall and a luncheon with President Theodore Roosevelt. Though she lived through both World Wars and the musical upheavals of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, her compositional style remained rooted in the melodic French Romanticism exemplified by her contemporaries Fauré, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns.

The two works on this program were presumably written for Chaminade to perform herself, featuring a level of virtuosity beyond the reach of the amateur musicians who revered her. Automne, the second of Six Études de Concert, Opus 35, is a lyrical song without words, marked by a dramatic middle section full of stormy, Lisztian flourishes. In Thème varié, Opus 89, Chaminade takes a lilting Couperin-like theme of her own devising through a series of gracefully embroidered variations.

—Steven Ziegler

Piano Trio No. 3 in C minor, Opus 101

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1886

Johannes Brahms often found himself at his most productive during his summer vacations at some bucolic location distant from his Vienna home. The three summer months of 1886 he spent at Hofstetten, near Lake Thun in Switzerland, and in that short span he produced a remarkable freshet of masterworks: his F-major Cello Sonata, his A-major Violin Sonata, his C-minor Piano Trio, most of his D-minor Violin Sonata, and several songs. This is an extraordinary lineup by any measure, not just for its consistently superb quality but also for the density of achievement in so little time and the variety of emotional terrain these pieces cover.

The C-minor Piano Trio is a tightly-coiled composition, tense, nervous, and compact. It springs into action with a furious outburst, rather in the mode of a Beethovenian eruption, and Brahms then provides contrast through a second theme, played in octaves by the violin and cello, that encapsulates aristocratic poise. These materials are worked out with extreme economy and in a way that seems unusually abstracted, to the extent that the rhythmic pulse sometimes is obscured into apparent irrelevance in the face of contrapuntal push-and-pull. “Smaller men,” wrote Brahms’s friend Heinrich von Herzogenberg, “will hardly trust themselves to proceed so laconically without forfeiting some of what they have to say.” Indeed, Brahms says what he needs to with exceptional concentration here, even to the extent of pointedly deleting the traditional repetition of the exposition section.

The second movement is so reticent as to seem almost to apologize for its existence, the more so in light of the granitic toughness of the first movement. Here we have a mere will-o’-the-wisp of a scherzo, and if we sometimes glimpse it only indistinctly—its evanescence underscored by the muting of the strings—at least we are back on firm ground so far as the rhythm is concerned, since Brahms casts this in a more reliably discernable duple meter.

With the third movement we turn to an ultra-familiar Brahmsian landscape: an intermezzo, characteristically marked Andante grazioso. But where most Brahms intermezzos are calm and consoling, perhaps dreamy, this one may leave listeners feeling uneasy in a way that seems hard to pin down. It’s the rhythm that is unstable. Brahms sets his music in groupings of three measures—specifically, a measure in 3/4 meter followed by two measures in 2/4 meter, with that pattern then repeated over and over. The Brahms biographer Jan Swafford wondered if this rhythmic bravery might reflect Brahms’s appreciation of Hungarian traditional music, with its complex rhythmic juxtapositions, and the musicologist Michael Musgrave avers that this movement testifies to Brahms’s “love of the irregular meters of Serbian folk song.” By now we will understand that this piano trio is to a large extent “about” rhythmic variety, and the finale carries that idea through to the end.

One of Brahms’s favorite rhythmic hallmarks is the hemiola, which is, as The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians defines it, “the articulation of two units of triple meter as if they were notated as three units of duple meter.” Hemiolas abound in this final movement, as do other falsely placed accents, and the cross-rhythms can throw a listener into rhythmic puzzlement at times. Finally at the end, the rhythmic restiveness is tamed into regularity and a brief coda, now in the major mode, brings to the work to a relatively upbeat end.

—J.M.K.

About the Artists

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

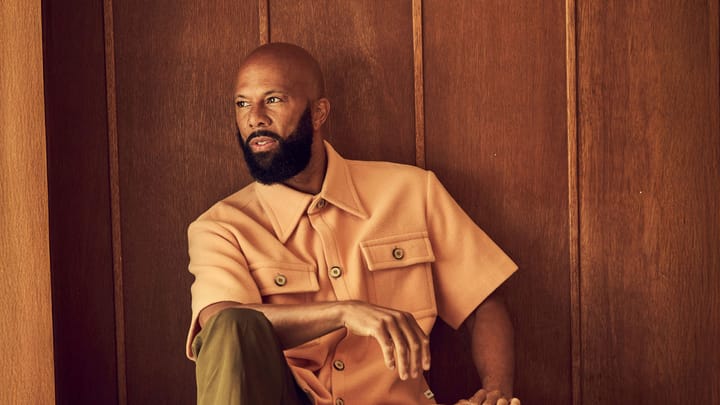

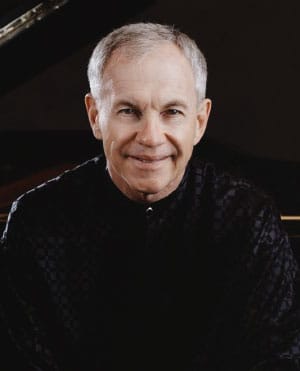

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of last season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.