In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, March 13, 2025, at 2:00pm

Friday, March 14, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, March 15, 2025, at 7:30pm

Preconcert talk by Scott Foglesong: on stage Thursday at 1:00pm

Elim Chan conducting

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Selections from Swan Lake, Opus 20 (1876)

Scène moderato

Valse

Danse des cygnes (Allegro moderato)–Pas d’action (Andante)

Scène finale

Intermission

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Opus 74, Pathétique (1893)

Adagio–Allegro non troppo

Allegro con grazia

Allegro molto vivace

Adagio lamentoso–Andante

Elim Chan’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Thursday matinee concerts are endowed by a gift in memory of Rhoda Goldman.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Symphony No. 6, Pathétique, was Tchaikovsky’s final work. Just nine days after he conducted the premiere, he died unexpectedly. The nickname may have been suggested by the composer’s brother, Modest, to convey the work’s mood of exquisite longing. Tchaikovsky himself suggested there was a secret story behind the music, but he never revealed what it was: “let them guess.”

Selections from Swan Lake, Opus 20

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1875–76

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1937. Efrem Kurtz conducted excerpts with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Most Recent—June 2011. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted music from Act III. (MTT more recently conducted the International Dances from Swan Lake in January 2015.)

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, castanets, snare drum, bass drum, chimes, and glockenspiel), harp, and strings

Duration: About 25 minutes

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s path as a composer was often difficult and came about after an earlier career change. He was a precocious child, not only in music, but in poetry, French, and other topics. But he was placed on a track outside of music at the age of 12. He spent seven years at the school of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg, from 1852 through 1859, and was even assigned a job at the Ministry of Justice before he realized he needed to devote his life to music. He took music lessons during his time at the School of Jurisprudence, but it was not until the fall of 1862 when he began his studies at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory that his world as a composer began to expand. Under his teacher Anton Rubinstein, he worked tirelessly to hone the skills he needed to forge his way as a composer. He studied theory, composition, piano, flute, and organ. Eventually he was introduced to Rubinstein’s younger brother, Nicolai, who had founded the Moscow Conservatory. Tchaikovsky accepted a job at the Moscow Conservatory despite his disdain for teaching, and would spend much of the rest of his life in that city and its surrounding environs.

Tchaikovsky was no stranger to the theater when he composed his first ballet, Lebedinoe ozoe (Swan Lake) in 1875–76. He had written operas and other incidental music, but Swan Lake was his first ballet. It was also his first work for the theater to garner wider attention, and is today one of the most often performed ballets in the repertoire. The composer had been commissioned by the beleaguered Bolshoi Theatre in 1875, whose budget had been slashed due to poor ticket sales. The Bolshoi lacked solid leadership, but gave Tchaikovsky the opportunity to score a ballet. Tchaikovsky wrote to fellow composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1875, “I accepted the work partly because I need the money, and because I long cherished a desire to try my hand at this type of music.”

Swan Lake’s plot has a murky genesis, as the original scenario has no attribution. It bears a resemblance to Wagnerian opera (Swan Lake’s hero, Siegfried, shares the same name as the titular character in Wagner’s Siegfried, swans and a flood as with Götterdämmerung), as well as similarities to the Brothers Grimm, Ovid, and the stories of Johann Musäus. A recent discovery of previously missing archival materials during a 2015 renovation at the Bolshoi Theatre has established Vladimir Begichev (1838–91), a Bolshoi official and a Moscow noble, as the actual author of the ballet’s scenario. Begichev had encouraged Tchaikovsky’s interest in ballet, and the composer was happy to compose the score to Begichev’s story.

Ever the conflicted individual, Tchaikovsky later had mixed feelings about Swan Lake. In his diary, he wrote that hearing it at an 1888 Prague performance gave him “a moment—just one—of absolute happiness.” He also wrote in 1877 that he was “ashamed” of the work when it was panned by critics during early performances. The early critical reception was lukewarm in part because of the choreography, a confusing plot line, and all-out chaos onstage during parts of the ballet.

The version of Swan Lake that balletgoers hear today is most often not that which was performed in Tchaikovsky’s lifetime. The choreographer of the premiere, Wenzel Reisinger (1828–93), found the score difficult to work with and postponed the premiere from December 1876 to February 1877. His choreography was described as “bland” and “boring,” and not commensurate with the seriousness of Tchaikovsky’s music. In 1895, after the composer’s death, the original Bolshoi version of 1877 was reworked by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, who staged a new version of Swan Lake with music arranged by Riccardo Drigo. Most modern productions are based on this version.

The Story and Music

The scenario for Swan Lake is a story of love, deception, and ultimately, sacrifice. The innocent princess Odette has been cursed by her evil stepmother to live out her days as a swan, alongside a flock of her maiden friends. They swim in a lake of tears shed over the death of Odette’s mother, transforming into their human figures only at night. Although she is protected by a crown given to her by her grandfather, Odette’s curse can only be broken by a promise of everlasting love by one who has never been in love before. Enter Prince Siegfried, who has recently been informed by his mother that now that he is 21, it is time for him to get married. His mother arranges a matchmaking ball for him the next evening. He takes his crossbow and goes hunting at the lake, where he spies a flock of swans. Siegfried is about to loose an arrow when Odette appears in human form and tells him about her curse. He falls instantly in love and agrees to pledge his undying love to her at his mother’s ball, thereby freeing her from her curse.

If only it were that easy. At the ball, the nefarious Baron von Rothbart appears with his proxy Odile, an evil Odette doppelgänger, to deceive the prince. One cannot blame Siegfried for declaring his undying love to the wrong swan maiden as the two roles are almost always performed by the same dancer. As soon as Siegfried utters his oath, Baron von Rothbart uncovers the deception and reveals Odile for who she truly is. Siegfried rushes to the lake and apologizes to Odette. She accepts his apology but cannot live with her curse any longer and decides to throw herself into the lake. There are several versions of the ending, some happy, and others not so much. In the original Begichev scenario, Siegfried throws the crown into the water, and the evil stepmother, in the form of an owl, snatches it up. A storm swallows the lovers to their watery deaths.

The musical selections on this concert, compiled by conductor Elim Chan, include some of the most recognizable themes from the ballet. The first number, from the beginning of Act II, opens with the famous “swan theme.” A tenuous arpeggio in the harp beckons the plaintive oboe to play the famous melody for the first time, as Odette appears. The Valse in Act I is one of the iconic numbers from the ballet, a waltz performed by the villagers in celebration of Prince Siegfried’s coming of age. It is graceful and warm, a naïve dance before the main action of the ballet unfolds. The Danse de cygnes of Act II includes the “dance of the little swans,” in which four members of the corps de ballet clasp hands and dance close to each other, turning and bowing their heads in perfect unison. They seem to be huddled together like cygnets trying to keep warm from the cold. Immediately following the cygnets is a pas d’action between Odette and Prince Siegfried, with material borrowed from Tchaikovsky’s earlier opera Undine. A sonorous violin solo accompanies the two lovers. The suite closes with the final scene of the ballet, in which both Odette and Siegfried meet their end, or find their happy ending as spirits in the afterlife after breaking the curse through giving up their lives.

Like the Pathétique Symphony on this concert’s second half, Swan Lake deals with universal themes of life and death. As Tchaikovsky scholar Simon Morrison notes, “death is compulsory; there’s no avoiding it; no happy endings, neither love nor religion nor art nor psychiatric counseling nor healthy living, can transcend it.”

The lovers believe that they can break the curse, that love prevails over all. But in the end, love cannot transcend the inevitable. Although some productions provide a lieto fine, where Siegfried defeats von Rothbart and is reunited with Odette for them to live happily ever after, the original, more tragic version provides a window into the beauty of love over life.

—Alicia Mastromonaco

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Opus 74, Pathétique

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Work Composed: 1893

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1911.

Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—May 2022.

Nathalie Stutzmann conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, bass drum, and tam-tam), and strings

Duration: About 45 minutes

The sixth and final symphony Tchaikovsky wrote, the Pathétique, has come to symbolize notions surrounding the composer’s death just as much as it epitomizes his late compositional style. He conducted the premiere in Saint Petersburg in October 1893, and nine days later he was dead. His stylistic precarity between the Russian folk-art music of the Mighty Handful (his more nationalistic colleagues Balakirev, Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Borodin) and late 19th-century central European Romanticism is on full display here, in his final published work. Amid the intrigue of the composer’s untimely death at age 53, there was much speculation over whether the composer wrote this symphony as his musical farewell, as if he knew somehow he was about to die (he did not, and in fact feared a sudden death). The Russian title, Pateticheskaya, translated into the French Pathétique, alludes to the pathos, the hyper-emotionality throughout the work. But beyond that, it is difficult to surmise whether the symphony had a deeper storyline. It was Tchaikovsky himself who teased at a program for his Sixth Symphony, in an 1893 letter to his nephew Vladimir “Bob” Davidov, to whom the symphony is dedicated. He confided to his nephew that the symphony he was working on would have a program, “but such a program that will remain an enigma to everyone—let them guess.” Whether he wrote this because he actually had a program in mind or to generate interest remains the true mystery.

The Sixth Symphony as we know it is not the first version of the work. He first sketched music that he hoped would be a “grandiose” symphony between April and June 1891, but put it away until 1892, when he composed the first and last movements. He continued on the symphony until December, when he abruptly canned the entire work. Rather than actually destroy all the music, however, he repurposed some of it, turning one movement into part of his Piano Concerto No. 3, and using other music in an Andante and Finale, which was published as Opus 79. The music that would become his Sixth Symphony was composed swiftly between February and March of 1893, the first movement of which he told his nephew he composed over the course of merely five days.

The Music

The Pathétique is a continuation of Tchaikovsky’s approach to the symphony in some ways, and a striking departure in others. The first movement is densely packed with allusions to both Western classical forms and Russian liturgical quotation. The middle of the first movement quotes a hymn from the Orthodox service for the departed, the panikhida. “With the saints, give rest, Christ, to the souls of Thy servant,” is the line to help the soul of the deceased into the realm beyond.

The first movement contains the double nature of the heaviness of mortal drudgery and the ephemerality and radiance of the afterlife. The second movement is a waltz, albeit in an undanceable 5/4 time signature. It is as beautiful as it is perplexing, a lilting melody that is memorable, and seeming to be missing something. The third movement is a scurrying scherzo with march-like fanfares throughout. It is a cyclical movement, “endlessly iterated,” a “perpetuo moto,” writes Simon Morrison.

The Adagio lamentoso is the only final movement of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies to end in a minor key. The falling theme attempts to right itself throughout the movement, to claw its way back from the precipice of nonexistence. But in the end, the unavoidable becomes inevitable; the symphony goes gently into the passive embrace of night.

Tchaikovsky’s death is surrounded by intrigue, mystery, and whispers of its planned occurrence by the composer himself. While it does make for a far more interesting story to believe that Tchaikovsky wrote the symphony as a musical suicide note, this theory has been discredited. Scholars now believe that Tchaikovsky was likely one of the many Russians who perished of cholera during the epidemic of 1892–93. That he succumbed to the disease just nine days after the premiere of his Pathétique Symphony is a tragic coincidence.

Tchaikovsky was intently focused on his legacy, his desire to reach the pinnacle of his compositional abilities, and his sense of valediction in this symphony, from a philosophical and musical perspective. To inextricably link this symphony so directly with the composer’s death is to do the work a disservice. It is true that the composer conceived of the piece as the conclusion of his compositional career, a grand symphony that would be part of his legacy. But taken on its own, outside of any extramusical context, the symphony is a masterwork in and of itself. Even Tchaikovsky, as hypercritical as he could be, wrote in a letter to his nephew Bob Davidov, “I absolutely consider it to be the best, and in particular, the most sincere of all my creations. I love it as I have never loved any of my other musical offspring.”

—A.M.

About the Artist

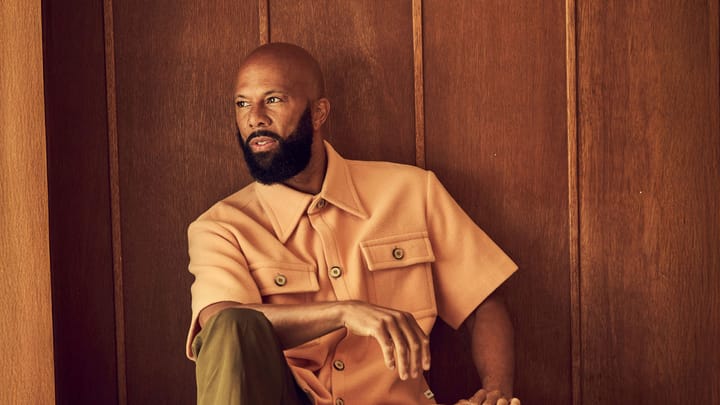

Elim Chan

Elim Chan served as principal conductor of the Antwerp Symphony between 2019 and 2024 and as Principal Guest Conductor of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra between 2018 and 2023. She debuted at the BBC Proms with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 2023, and returned for the First Night of the Proms 2024. Last summer also saw her reunite with the Los Angeles Philharmonic for the opening of the Hollywood Bowl’s classical summer season and with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra at the Edinburgh International Festival, as well as her debuts with the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra for the opening of the Salzburg Festival and with the Potsdam Kammerakademie for the opening of Beethovenfest Bonn.

Highlights of Chan’s 2024–25 season include two tours with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra as well as return engagements with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Vienna Symphony, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Finnish Radio Symphony, and Sydney Symphony. She also debuts with the Pittsburgh Symphony, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia, and Melbourne Symphony. Previous debuts include the Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Boston Symphony, Staatskapelle Berlin, Staatskapelle Dresden, Philharmonia Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in January 2023.

Born in Hong Kong, Chan studied at Smith College and at the University of Michigan. In 2014 she became the first female winner of the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition and went on to spend her 2015–16 season as assistant conductor at the London Symphony, where she worked closely with Valery Gergiev. In the following season, Elim Chan joined the Dudamel Fellowship program of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. She also owes much to the support and encouragement of Bernard Haitink, whose masterclasses she attended in Lucerne.