In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, November 7, 2023, at 7:30pm

Friday, November 8, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, November 9, 2024, at 7:30pm

Nicholas Collon conducting

Thomas Adès

Three-piece Suite from Powder Her Face (2007)

Overture

Waltz

Finale

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 23 (1875)

Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso–Allegro con spirito

Andantino semplice–Prestissimo

Allegro con fuoco

Conrad Tao

Intermission

Edward Elgar

Enigma Variations, Opus 36 (1898)

Theme: Andante

C.A.E. (Andante)

H.D.S.-P. (Allegro)

R.B.T. (Allegretto)

W.M.B. (Allegro di molto)

R.P.A. (Moderato)

Ysobel (Andantino)

Troyte (Presto)

W.N. (Allegretto)

Nimrod (Adagio)

Dorabella–Intermezzo (Allegretto)

G.R.S. (Allegro di molto)

B.G.N. (Andante)

***Romanza (Moderato)

E.D.U.–Finale (Allegro)

Nicholas Collon’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Three-piece Suite from Powder Her Face

Thomas Adès

Born: March 1, 1971, in London

Work Composed: 1994–95 (Suite arr. 2007)

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, 2 clarinets,

bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, suspended cymbals, high-hat, antique cymbal, tam-tam, tambourine, snare drum, small bongo, roto toms, brake drum, monkey drum, bass drum, pedal bass drum, wood block, temple blocks, guiro, rattle, vibraslap, pop gun, washboard, whip, glockenspiel, and xylophone), and strings

Duration: About 12 minutes

Powder Her Face is a 1995 chamber opera by Thomas Adès based on Margaret Campbell, the duchess of Argyll, whose real-life 1963 divorce created a sensational sex scandal in England. Her husband accused her of infidelity, introducing a set of explicit Polaroid photos as evidence in court. Later in life, she squandered her fortune and ended up living in a hotel suite. This is where the opera finds her, as she slips into the past, conjuring scenes from the 1930s through ’70s.

Both the 24-year-old Adès and his librettist, Philip Hensher, were drawn to the tabloid tale when they were commissioned by London’s Almeida Opera. “The Almeida didn’t disguise their complete bewilderment at what we were proposing,” Hensher told The Guardian in 2008. “The director of opera said he had no idea what I meant when I said I wanted it to seem like scenes from the life of a medieval saint, only with shopping expeditions instead of miracles.” The opera was met with a mix of outrage and admiration after its premiere—and is now one of the most frequently produced operas of the late 20th century.

Since then, Adès has become one of Britain’s most popular composers, writing two more operas: The Tempest (2003) for the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and The Exterminating Angel (2016) for the Salzburg Festival, Royal Opera House, Metropolitan Opera, and Royal Danish Opera. He has also written extensively for the concert hall, including a recently acclaimed piano concerto for the Boston Symphony, and he performs internationally as a conductor and pianist.

Alongside these new works, Adès has revisited Powder Her Face over the years, first extracting three movements in 2007 as Dances from Powder Her Face. Since the original score used only a small pit band, he rescored the music for large orchestra, creating lusher sonorities and arranging some of the vocal lines for instruments. The suite was premiered by the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Aldeburgh Festival in June 2007, where Adès was artistic director. Later he created two longer suites from the opera, and in 2018 lightly retouched the original and renamed it Three-piece Suite (Suite No. 1).

The Music

The Overture and Finale are the opera’s first and last numbers, so we hear its heart-racing opening and spluttering ending on either side of a radically condensed middle. Adès’s music is so vivid it keeps its narrative coherence even in this shortened form.

In the Overture, a maid and an electrician fool around in the duchess’s hotel room, laughing and mocking the destitute old woman behind her back. A woozy tango evokes her glamorous youth through the fog of memory, while two clarinets set the tawdry tone that defines the whole suite.

The Waltz flashes back to her 1934 wedding. In the original aria, a sardonic waitress observes, “Fancy being rich. Fancy being lovely. Fancy having money to waste, and not minding it . . . She doesn’t look happy. She looks rich.”

The Finale returns to the hotel room in 1990, where the elderly duchess is being evicted. The music comes apart at the seams, disintegrating as she slips into denial. In what Adès originally termed the “Ghost Epilogue,” the maid and electrician continue to fool around as they strip the bed, fold the sheets, quit their hijinks, and turn out the lights.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Previous versions of this note appeared in the program books of the St. Louis Symphony and Melbourne Symphony.

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 23

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1874–75

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1912. Henry Hadley conducted with Tina Lerner as soloist. Most recent—September 2013. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Yefim Bronfman as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto in B-flat minor was his first of three in that genre, though his other two are nearly as obscure as the first is famous. Though he was already 34 when he wrote this work, in late 1874, he had not quite reached the tipping point in his career. He had received a good education in Saint Petersburg. After studies at the School for Jurisprudence, which channeled its students towards legal and civil-service careers, he entered the Saint Petersburg Conservatory when it opened in 1862 and graduated in 1865. His principal teacher was the highly respected Anton Rubinstein, an acclaimed pianist and the school’s director.

Anton’s younger brother, Nicolai, was by all reports also a stupendous pianist. His work in Moscow served as a sort of counterpart to Anton’s in Saint Petersburg, and in the mid-1860s he founded a school there, destined to become the Moscow Conservatory. He recruited Tchaikovsky as a professor of music theory, sweetening the deal by throwing in free lodging at his own home. Tchaikovsky accepted and moved to Moscow in January 1866.

If Anton Rubinstein had been most responsible for refining Tchaikovsky’s skill as a composer, Nicolai was the figure most responsible for championing his music and disseminating his growing fame. By the end of 1874, Nicolai had conducted not only the premiere of Romeo and Juliet but also the premieres of his first two symphonies and the symphonic poems Fatum and The Tempest. Tchaikovsky appreciated his boss’s advocacy, and in 1872 he composed a serenade for chamber orchestra to mark Nicolai’s name day. When Tchaikovsky bravely forged into the genre of the piano concerto, in late 1874, it was perfectly logical on a musical, professional, and personal level that he should run his new piece past Nicolai Rubinstein.

The two decided to have a look at the score just before a Christmas Eve party. In 1878, the composer recounted the experience in a letter to his elusive patron, Nadezhda von Meck. His account reveals how vividly the event was seared into his memory.

I played the first movement. Not a word, not a single observation! If you only knew how uncomfortably foolish one feels when one places before a friend a dish one has prepared with one’s own hands, and he eats thereof and—is silent! At least say something: if you must, find fault in a friendly way, but, for heaven’s sake, speak—say something, no matter what! But Rubinstein said nothing; he was preparing his thunder. . . .

He spoke quietly at first, but by degrees his passion rose, and finally he resembled Zeus hurling thunderbolts. It appeared that my Concerto was worthless and absolutely unplayable, that the passages were contrived and so clumsy as to be beyond correction, that the composition itself was bad, trivial, and commonplace, that I had stolen this point from somebody and that point from somebody else, that only two or three pages had any value whatsoever, and all the rest should be either destroyed or entirely remodeled. . . .

He repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places where it would have to be completely revised, and said that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing this thing of mine at his concert. “I shall not alter a single note,” I replied. “I shall publish the work exactly as it stands!” And this I did.

Unlike Rubinstein, the German pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow could scarcely have been more delighted with the work, and he resolved to unveil it during his upcoming North American tour—which explains why this ultra-familiar emblem of the “Russian style” received its premiere in 1875 in Boston, played by a German pianist on an American Chickering piano with an orchestra of Massachusetts freelancers. The piece created a sensation throughout the North American tour, and its popularity has never faded since.

In fact, the score Rubinstein revealed was not exactly the score as we know it today. Apparently there was considerable room for improvement—including details of the keyboard writing—and Tchaikovsky would go on to put his piece through two revisions, the second of which, from 1889, brought the work into the form in which it is nearly always heard today.

The Music

At this distance we can look back on Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 as the breakthrough work into his entirely mature style. It’s packed with memorable melodies, it’s generous with virtuosic display, its rhythmic impulse is so buoyant as to suggest ballet, and it wears its heart on its sleeve.

The Allegro begins with the horns intoning a somewhat stern motif of four falling notes, which the full orchestra punctuates with crashing commas. It is one of the great openings, and it would require something similarly out-of-the-ordinary to proceed without a let-down. This Tchaikovsky manages, thanks to his first theme, which is an expansion of the horns’ opening motif. Given the magnificence of this theme, it is astonishing how little use Tchaikovsky makes of it. It dominates the first ten pages of the score and then simply evaporates, not to be heard again. The introduction is rounded off to some extent in the way it began, which is to say with the sound of the horns—though what was a forceful horn pronouncement at the opening is, at the introduction’s end, a quiet, haunting, repeated horn note. The remainder of the movement unrolls in Tchaikovsky’s typically rhapsodic fashion. The piano tune that takes over where the introduction leaves off has a skipping quality, and Tchaikovsky reported that he owed this nervous, stumbling allegro melody to a blind beggar he heard singing at a fair. Other themes are introduced, most developed only slightly, and finally the movement cascades into a hugely demanding cadenza for the soloist, a passage requiring sharpshooter aim and wrists of steel.

Knowing as we do that Tchaikovsky would soon emerge as one of history’s finest ballet composers, it is easy for us to imagine the opening of the second movement as a prima ballerina’s gravity-free adagio. The fact that the strings play with mutes installed throughout this movement adds to the spectral quality.

The opening of the finale is based on a Ukrainian folk dance. After this, the violins are given a tender tune that, towards the movement’s end, will be transformed into a sweeping song of triumph.

—James M. Keller

Enigma Variations, Opus 36

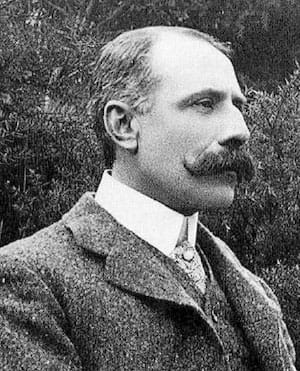

Edward Elgar

Born: June 2, 1857, in Broadheath, Worcestershire, England

Died: February 23, 1934, in Worcester, England

Work Composed: 1898

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1925. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—July 2023. Anna Rakitina conducted.Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (snare drum, triangle, bass drum, and cymbals), organ, and strings

Duration: About 30 mins

It’s not the Enigma that has made Edward Elgar’s Variations endure for more than a century. It’s the warmth and sincerity with which he portrays real people who were important to him. Friendship, after all, is a fundamental human need, but it ranks far behind romantic love in terms of musical tributes.

Elgar stumbled on the theme on October 21, 1898, while improvising at the piano. Alice, his wife, was listening, and called out that it was a good melody. He began to vary it, imagining how his friends might write it “if they were asses enough to compose.” At first it was just a parlor trick, but then he began to wonder if it could be the framework for a real piece. Years later, he described the variations as “begun in a spirit of humor and continued in deep seriousness.”

The word “Enigma” was scrawled on the first page of Elgar’s manuscript, above the theme. It was jotted there by August Jaeger, Elgar’s close friend and the subject of the Nimrod variation. Early performances were simply labeled “Variations on an Original Theme,” but soon “Enigma” became part of the accepted title. Elgar stated:

The Enigma I will not explain—its “dark saying” must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connection between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme “goes,” but is not played. So the principal Theme never appears . . . the chief character is never on the stage.

Taken literally, Elgar seems to be saying there is a secret musical theme that can be played over the music, in synch with its harmony and rhythm. “The theme is so well known that it is extraordinary that no one has spotted it,” Elgar later added. But the fact is, nobody in 125 years has ever found a very compelling, let alone definitive, solution. Another possibility is that there is no hidden tune, just an abstract “theme”: perhaps something as anticlimactic as “friendship” or some kind of inside joke. (More elaborate theories based on mathematics, Bible codes, or Shakespearian allusions should be approached with skepticism.)

Elgar was 41 when he began the variations. He already had a publishing deal with Novello and had written a number of successful choral works, but was hardly a household name. The Enigma Variations made him suddenly famous after the premiere led by Hans Richter at St. James Hall in London on June 18, 1899—it became (and arguably remains) the most celebrated piece of British orchestral music of all time.

The Variations

The piece unfolds as a theme and 14 short variations. Most are labeled with initials, lending an even more enigmatic appearance—but the subjects were easily identified and confirmed by Elgar. The theme itself is cool and gray.

C.A.E. This is Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer’s wife. They were happy together, and when she died in 1920, he mostly stopped composing.

H.D.S.-P. Hew David Steuart-Powell was a pianist Elgar often played chamber music with. His variation is perky and excited.

R.B.T. Richard Baxter Townshend was an Oxford classicist who also performed in amateur theater productions and rode a bicycle around town. Here he seems a little pompous, in a good-natured way—an eccentric professor.

W.M.B. Here we have William Meath Baker, a country squire, in a brief, bombastic variation.

R.P.A. Richard Penrose Arnold was the son of the poet Matthew Arnold and also a pianist. “His serious conversation was continually broken up by whimsical and witty remarks,” Elgar recalled.

Ysobel This time Elgar offers a respelling instead of initials for Isabel Fitton, an amateur violist he played chamber music with. Naturally the viola section takes the starring role with an easy-going attitude.

Troyte was the middle name of Arthur Griffith, an architect and watercolorist. He was apparently profoundly unmusical, and this noisy variation imagines Elgar attempting to teach him to play the piano in vain.

W.N. is Winifred Norbury, an upper-class woman who lived in a grand Georgian-era house. The movement reflects her stately demeanor and decorative sense.

Nimrod is a character from Genesis, “a mighty hunter before the Lord.” In a translation pun, Elgar uses it to refer to August Jaeger, whose last name means “hunter” in German. This is the most substantial movement and the centerpiece of the set. Jaeger worked in the office of Elgar’s publisher, Novello, and became a close confidante who supported the composer through stretches of depression.

Dorabella (Intermezzo) This is Dora Penny, whose stepmother was friends with Alice. Elgar grew close to the young woman, and probably found her attractive. The variation suggests a little bit of flirting. A few years later he would send her the “Dorabella Cipher,” a letter with three lines of curlicues containing another uncracked message.

G.R.S. George Robertson Sinclair was the organist at Hereford Cathedral, but Elgar’s music portrays his dog, Dan. “The first few bars were suggested by a great bulldog . . . falling down the steep bank into the River Wye; his paddling up stream to find a landing place; and his rejoicing bark on landing.”

B.G.N. Basil Nevinson was a scientist and artist. This lyrical variation captures someone sensitive and a bit sad.

***Romanza is a portrait of Lady Mary Lygon, who was sailing to Australia as Elgar wrote the Variations. He quotes from Felix Mendelssohn’s overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, and you can hear the churning of the ocean liner and surrounding waves.

E.D.U. This is not a friend at all, but rather Elgar himself. The regal, march-like music recalls the English festival pieces he had written earlier in his career. At the end of the score, he wrote a quote from Tasso, the Italian Renaissance poet: “Bramo assai, poco spero, nulla chieggio.”

“I long for much, hope for little, and ask for nothing.”

—B.P.

About the Artists

Nicholas Collon

Nicholas Collon is the founder and principal conductor of Aurora Orchestra and has been chief conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony since 2021. He was chief conductor of the Residentie Orkest The Hague from 2016–21, and was principal guest of the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne from 2017–22. With the Finnish Radio Symphony, he has toured to the BBC Proms, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, and to Germany and Estonia. Their expanding discography together for Ondine includes discs of Sibelius, Lutosławski, Adès, and Wennäkoski, which won the 2023 Gramophone Award for Best Contemporary Recording. Aurora Orchestra is in residence at Kings Place and the Southbank Centre, and has recorded for Deutsche Grammophon and Warner, winning the Echo Klassik Award for Classical Without Borders in 2015.

Collon debuted with the Dresden Staatskapelle last spring, and this season appears with the Munich Philharmonic, WDR Symphony, and Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin. He regularly conducts the BBC Philharmonic, City of Birmingham Symphony, Orchestre National de France, Danish National Symphony, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, and Dresden Philharmonic, and has also guested with the Philharmonia Orchestra, London Philharmonic, Minnesota Orchestra, Toronto Symphony, Vienna Radio Symphony, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and Chamber Orchestra of Europe, among many others. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

In opera, he has led Peter Grimes and Don Giovanni for Oper Köln, Magic Flute at English National Opera, Wagner Dream at Welsh National Opera, Rape of Lucretia for Glyndebourne Touring Opera, and Turn of the Screw at the Aldeburgh Festival with Aurora Orchestra. Born in London, Collon is a violist, pianist, and organist by training, and studied at Clare College, Cambridge.

Conrad Tao

Conrad Tao’s 2024–25 season includes a return to Carnegie Hall performing Debussy’s 12 Études alongside Keyed In, a work arranged and improvised by Tao on the Lumatone keyboard. He also returns to the Dallas Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, and Baltimore Symphony. Further appearances include the Indianapolis Symphony’s opening gala, as well as performances with the Seoul Philharmonic and NDR Radiophilharmonie. He also continues his collaboration with dancer Caleb Teicher in a nationwide US tour.

Last season, Tao made his subscription debut with the Chicago Symphony and returned to the New York Philharmonic. He also celebrated Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary with recitals presented by the Cleveland Orchestra and Klavierfestival Ruhr. The season also saw concerts with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony, as well as performances celebrating the 100th anniversary of Rhapsody in Blue at the Berlin Philharmonie, Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, and Amsterdam Concertgebouw with the Kansas City Symphony. His companion piece to Gershwin’s Rhapsody, Flung Out, was commissioned by the Santa Rosa Symphony, Aspen Music Festival, and Omaha Symphony.

Tao was the recipient of a New York Dance and Performance Bessie Award for Outstanding Sound Design / Music Composition. He is also the recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant and was named a Gilmore Young Artist. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 2008 and became a Shenson Young Artist in 2023.