In This Program

Thursday, February 13, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, February 14, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, February 15, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, February 16, 2025, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Claude Debussy

Gigues from Images pour orchestre (1912)

Claude Debussy

Rondes de printemps from Images pour orchestre (1909)

Maurice Ravel

Piano Concerto in D major for the Left Hand (1930)

Yuja Wang

Intermission

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Piano Concerto No. 1, Opus 45 (1969)

Con grandezza

Andante (ma rubato)

Molto vivace

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Yuja Wang

Claude Debussy

Ibéria from Images pour orchestre (1908)

Par les Rues et par les chemins

Les Parfums de la nuit

Le Matin d’un jour de fête

These concerts are generously sponsored by the William and Gretchen Kimball Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Ravel wrote his Left-Hand Concerto for Paul Wittgenstein, a pianist who lost his right arm in the First World War. Rautavaara was the most prominent Finnish composer of the mid-20th century, with a strikingly original voice. In an intriguing link between past and present, he was once recommended for a scholarship by the elderly Jean Sibelius, and went on to be the first composition teacher of a young Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Images pour orchestre

Claude Debussy

Born: August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Died: March 25, 1918, in Paris

Work Composed: 1905–12

SF Symphony Performances: First complete—October 1986. Erich Leinsdorf conducted. (Ibéria was first performed in November 1916 with Alfred Hertz conducting, while Gigues was first performed in March 1938 and Rondes de printemps in January 1946, both with Pierre Monteux conducting.)

Most recent complete—May 2014. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted. (Ibéria was more recently performed in October 2018 with Pablo Heras-Casado conducting.)

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 2 piccolos, 2 oboes, English horn, oboe d’amore, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tambourine, castanets, chimes, drum, snare drum, tenor drum, and xylophone), 2 harps, celesta, and strings

Duration: Gigues—About 8 minutes.

Rondes de printemps—About 8 minutes. Ibéria—About 20 minutes.

Claude Debussy’s Images for Orchestra underwent a protracted gestation that extended across seven years, from 1905, when the composer conceived of Rondes de printemps and Ibéria as pieces for two pianos (settings he would never realize), until late 1912, when he completed Gigues. He considered these works a cycle in only the loosest sense, and he voiced no objections to their being performed as standalone pieces even after the complete set was played together in 1913. He expressed no strong preference about the order in which the three works should be presented, and he stated that the decision to place them as they appeared when they were printed as a group—Gigues, Ibéria, Rondes de printemps—was an arbitrary choice made by his publisher, Jacques Durand, and need not be followed in performance.

Durand’s ordering makes sense if one chooses to view the pieces as a set. While Gigues and Rondes de printemps are single movements, Ibéria is itself a three-movement suite. Placing it in the middle therefore yields an overall design that is symmetrical in a Palladian way; but then, maybe Classical balance is not what one is after in a Debussy performance. Since the tripartite Ibéria is so much longer, it can build its momentum without overwhelming its companions, and playing it separately and last doesn’t contravene the composer’s wishes.

Each of the component pieces of Images is based on a different national music: England for Gigues, which makes much use of a folk tune known as “The Keel Row”; France for Rondes de printemps; and Spain for Ibéria. Disparate opinions greeted these pieces when they were new. Ibéria was the first to be premiered, with Gabriel Pierné conducting the Orchestra of the Concerts Colonne in Paris on February 20, 1910. Pierné was about to repeat it when a counter-demonstration broke out in the hall, and the critics were similarly divided. Ten days later, when Rondes de printemps was unveiled (March 2, 1910, by the Orchestra of the Concerts Durand, with Debussy conducting), the audience reception was muted and reviewers were almost unified in their disapproval. Possibly they didn’t find the piece as sensuous as they might have expected of a “springtime” piece—one that spends a good deal of time quoting the French traditional song “Nous n’irons plus au bois” and that is headed by a couplet that exuberantly proclaims, “Vive le mai, bienvenu soit le mai / Avec son gonfalon sauvage!” (Long live May, let it be welcomed / With its rustic banner!).

Gigues was the last of the pieces to be written and premiered, led by Pierné at the Concerts Colonne on January 26, 1913, which was the first performance of the complete set. This time Debussy leaned on his colleague André Caplet for help with the orchestration, as he often did. In 1923, Caplet would publish an article in which he wrote of “Gigues . . . sad Gigues . . . tragic Gigues . . . The portrait of a soul in pain, uttering its slow, lingering lamentation on the reed of an oboe d’amore.” He continued: “Underneath the convulsive shudderings, the sudden efforts at restraint, the pitiful grimaces, which serve as a kind of disguise, we recognize . . . the spirit of sadness, infinite sadness.”

The movements of Ibéria do not quote actual folksongs; in fact, the composer’s early biographer Léon Vallas insisted that “it was not Debussy’s aim to write Spanish music, but rather to express truthfully his own impressions of Spain, a Spain of which he knew little or nothing, but which his imagination depicted with marvelous accuracy.” The piece was extolled by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla: “The echoes from the villages, a kind of sevillana—the generic theme of the work—which seems to float in a clear atmosphere of scintillating light; the intoxicating spell of Andalusian nights, the festive gaiety of a people dancing to the joyous strains of a banda of guitars and bandurrias . . . all this whirls in the air, approaches and recedes, and our imagination is continually kept awake and dazzled by the power of an intensely expressive and varied music.”

—James M. Keller

Piano Concerto in D major for the Left Hand

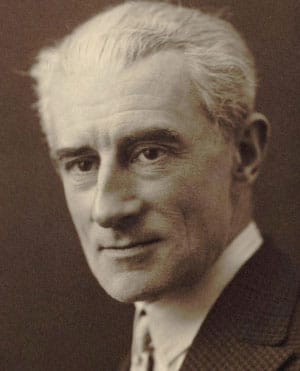

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1929–30

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1943. Pierre Monteux conducted with Maxim Shapiro as soloist. Most recent—April 2024. Karina Canellakis conducted with Cédric Tiberghien as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano (left hand), 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, wood block, snare drum, and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

Before they were musical collaborators, Maurice Ravel and Paul Wittgenstein served on opposing sides of the First World War. Ravel, nearly 40, hoped to be a pilot in the French Air Force but ended up as a supply vehicle driver because of his age and health. Wittgenstein, who had recently made his solo debut as a pianist, was called up to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Army. In late August 1914, during the Battle of Galicia in southern Poland, he was scouting Russian positions when he was shot in the elbow. He managed to return with his intelligence report before falling unconscious. When he woke up, he learned that doctors had amputated his right arm, and that during the surgery, the Russians had seized the field hospital and taken everyone there as prisoners of war.

Wittgenstein survived a grueling journey to Omsk, Siberia, where he was treated at a POW hospital and resolved to resume his musical career against all odds. First he drew a piano keyboard on a crate and practiced drumming his fingers on it, imagining how he could rework well-known pieces for one hand alone. Then for a few lucky months, he was interned at hotel where he was able to practice on an upright piano, but was eventually transferred to a fearsome gulag that had inspired Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The House of the Dead. At last he was returned to Vienna in a prisoner exchange.

Wittgenstein’s wartime ordeal was a world apart from the incredible material comfort and privilege with which he had grown up. His father, Karl Wittgenstein, made such a fortune in steel that he was called the “Austrian Andrew Carnegie.” Their palatial home was furnished with seven grand pianos and the children became deeply involved with music, art, and mathematics. Paul’s savant-like brother, Ludwig Wittgenstein, gave away his inheritance and became one of the 20th century’s most important philosophers. Their sister Margaret was painted by Gustav Klimt and analyzed by Sigmund Freud. But the family was troubled and visited by tragedy—three older brothers, as well as Margaret’s husband, all committed suicide.

In the decades after the war, Paul used his familial wealth to commission left-hand pieces from Ravel, Richard Strauss, Benjamin Britten, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Paul Hindemith, and Sergei Prokofiev. Despite working with such distinguished composers, he took a surprisingly transactional approach, treating the resulting works as his own property. This led to conflict with Ravel, who was incensed by Wittgenstein’s requests and criticisms over the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

In August 1929, at their first meeting to work through the music, Wittgenstein objected to a long solo passage, remarking, “If I had wanted to play without the orchestra I would not have commissioned a concerto!” Three years later, when Ravel heard Wittgenstein perform it in Vienna, he was shocked that the soloist had changed entire passages. “But that is not [what I composed] at all!” Ravel objected. “What you composed does not sound right,” Wittgenstein retorted.

Ravel demanded that Wittgenstein stick to the notes on the page, but the pianist countered: “No self-respecting artist could accept such a condition. All pianists make modifications, large or small, in each concerto they play.” Eventually the argument cooled and Wittgenstein came to see it as a “great work” without any changes. He toured with it widely, including a performance with the San Francisco Symphony and Pierre Monteux at the War Memorial Opera House in November 1946.

The Music

In a 1931 interview for London’s Daily Telegraph, Ravel explained: “In a work of this kind it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands.” And he succeeded—with athletic leaps and clever use of the piano’s sustain pedal, even a single hand can create layers of sound and both melody and accompaniment at the same time.

The concerto’s growling introduction features one of the few contrabassoon solos in the orchestral repertoire. This grows into a fanfare, which leads to the extended solo passage Wittgenstein had objected to. Ravel described the concerto’s one-movement strucutre: “After a first part in [a] traditional style, a sudden change occurs and the jazz music begins. Only later does it become evident that this jazz music is really built on the same theme as the opening part.”

—Benjamin Pesetsky

This note previously appeared in the program book of the St. Louis Symphony.

Piano Concerto No. 1, Opus 45

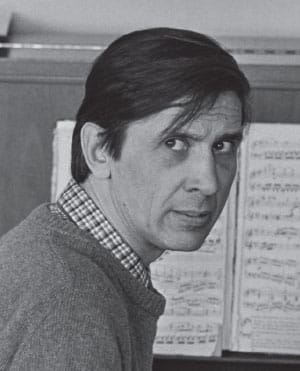

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Born: October 9, 1928, in Helsinki

Died: July 27, 2016, in Helsinki

Work Composed: 1969

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 clarinets, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, snare drum, and wood blocks), and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

Einojuhani Rautavaara came of age in Finland in the chaotic aftermath of World War II. He was no musical prodigy: by his own report, when he entered the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki to study with composer Aarre Merikanto, he “could only play the piano in a rudimentary fashion.” Still, he had felt musical stirrings early on. “When I was a small boy,” he wrote, “with no personal contact with music as yet, I painted ‘music’ on paper with watercolors and put these paintings on display as ‘compositions.’” In 1957, he graduated with a master’s degree from the Sibelius Academy. Three years earlier, in honor of Sibelius’s 90th birthday, the Koussevitsky Music Foundation had awarded that towering figure a study grant that he would bestow in turn on a promising young composer of his choice. He chose Rautavaara.

The grant enabled Rautavaara to leave for the United States to study with Roger Sessions (in 1955) and Aaron Copland (in 1956) at the Berkshire Music Center (Tanglewood). Work ensued at the Juilliard School, in Switzerland, and in Cologne. Rautavaara’s oeuvre emerged less from a conscious will toward eclecticism than from a voracious interest to keep current to all streams of musical modernity. His earlier works sometimes reflected neoclassicism in the style of Stravinsky, satirical parody à la Shostakovich, collage in the manner of Ives, or 12-tone serialism that recalls Schoenberg or Webern. His later pieces, from the 1970s, sometimes suggest Sibelius himself, and Messiaen’s influence also became apparent, particularly in Rautavaara’s penchant for birdsong and angel-infused mysticism.

Avant-gardists could be guarded about Rautavaara’s music after he rejected doctrinaire serialism, but gradually he became the most famous Finnish composer of his generation internationally—even the object of a cult following. In 1966, he returned to the Sibelius Academy; his pupils there included Esa-Pekka Salonen. Many awards came his way, including the Sibelius Prize (1965) and the Pro Finlandia Medal (1968). He was inducted into the Royal Swedish Academy in 1975, was named Commander of the Order of the Finnish Lion in 1985, and received the Finland Prize in 1997.

Rautavaara completed eight full-scale symphonies and some 40 other orchestral works, including many concertos: three for piano, two for cello, and others featuring flute, clarinet, violin, double bass, harp, organ, and percussion, in addition to his much-loved Cantus Arcticus, a concerto for (taped) birds and orchestra. He had grown into an impressive pianist by the time he wrote his Piano Concerto No. 1, in 1969. “I composed it for my own piano technique,” he later wrote, “and I performed it on several occasions as an orchestral soloist. It seems to me that it is important for a composer to serve in the capacity of a performing musician, at least at some stage.” It emerged at the point in his career when he had grown dissatisfied with the possibilities of highly regulated serialism and was discovering an idiosyncratic neo-Romanticism that could include Sibelian fervor. “I was also disappointed . . . with the then fashionable ‘ascetic’—and to my mind anemic—piano style, and I wanted in my concerto to restore the entire rich grandeur of the instrument, to write a concerto ‘in the grand style.’”

—J.M.K.

About the Artists

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

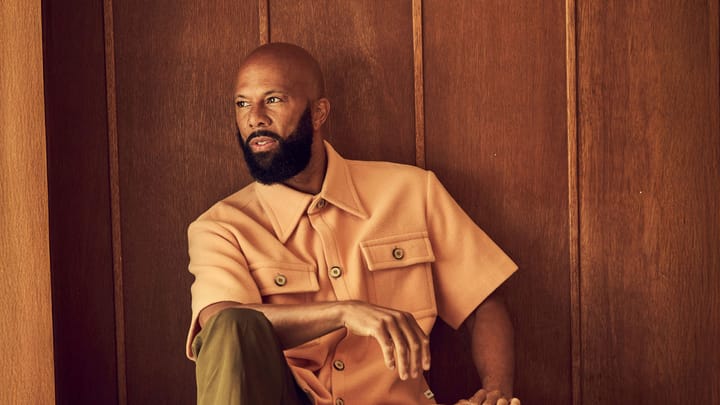

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang is celebrated for her charismatic artistry, emotional honesty, and captivating stage presence. She has performed with the world’s most venerated conductors, musicians, and ensembles, and is renowned not only for her virtuosity, but her spontaneous and lively performances.

Her skill and charisma were recently demonstrated in a marathon Rachmaninoff performance at Carnegie Hall with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Yannick Nézet-Séguin. This historic event celebrating 150 years since the birth of Rachmaninoff included performances of all four of his concertos plus the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. The 2022–23 season also saw Wang performing the world premiere of Magnus Lindberg’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the San Francisco Symphony and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Wang was born into a musical family in Beijing. After childhood piano studies in China, she received advanced training in Canada and at the Curtis Institute of Music under Gary Graffman. Her international breakthrough came in 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich as soloist with the Boston Symphony. Two years later, she signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and has since established her place among the world’s leading artists, with a succession of critically acclaimed performances and recordings. She was named Musical America’s Artist of the Year in 2017, and in 2021 received an Opus Klassik Award for her world-premiere recording of John Adams’s Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel.

As a chamber musician, Wang has developed long-lasting partnerships with several leading artists. This season, she embarks on an international duo-recital tour with pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, including a return to the Great Performers Series at Davies Symphony Hall (March 2). Wang made her San Francisco Symphony debut in February 2006 and became a Shenson Young Artist later that year. She can be heard on the Masterpieces in Miniature album on SFS Media.