In This Program

The Concert

Friday, December 6, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, December 7, 2024, at 7:30pm

Stephen Stubbs conducting

George Frideric Handel

Messiah, A Sacred Oratorio (1741)

Part One

Intermission

Part Two

Part Three

Amanda Forsythe soprano

John Holiday countertenor

Aaron Sheehan tenor

Douglas Williams baritone

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

These concerts are sponsored by the James Schwabacher Vocal Artists Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

The text was adapted for Handel by Charles Jennens (1700–73), who creatively assembled passages from the King James Bible and Book of Common Prayer into a three-part libretto. Part One includes the prophecy of Christ’s birth and the Nativity story, including such highlights as “For unto us a Child is born.” Part Two tells of his life on earth and the spreading of his message by the Apostles, ending with the famous “Hallelujah” chorus. Part Three focuses on the response of believers and the promise of salvation, with the aria and trumpet solo “The trumpet shall sound” and a glorious Amen.

Messiah, A Sacred Oratorio

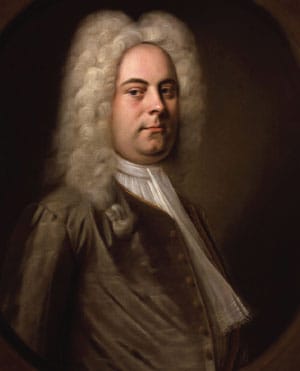

George Frideric Handel

Born: February 23, 1685, in Halle, Margraviate of Brandenburg

Died: April 14, 1759, in London

Composed: 1741

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1925. Alfred Hertz conducted with the San Francisco Municipal Chorus and Lorna Lachmund, Paul Althouse, Belle Montgomery, and Arthur Middleton as soloists. Most recent—December 2023. Jonathan Cohen conducted with the San Francisco Symphony Chorus and Joélle Harvey, Jennifer Johnson Cano, Nicholas Phan, and Michael Sumuel as soloists.

Instrumentation: 4 vocal soloists (soprano, alto [countertenor], tenor, and bass [baritone]), chorus, 2 oboes, bassoon, 2 trumpets, timpani, basso continuo (harpsichord and organ), and strings

Duration: About 150 minutes (including intermission)

George Frideric Handel was at heart a man of the theater, whether the opera stage or the “ecclesiastical theater” of the oratorio. He infused everything he wrote with drama. That’s one of the qualities that makes his music so memorable: his arias, vocal ensembles, and choruses, not to mention his concertos, sonatas, and sinfonias, contain emphatic turns of phrase that engrave themselves on the mind. In an age that valued adherence to Classical standards and, by extension, did not disdain a certain interchangeability of style, Handel exhibited brash independence of musical character. In his mature works, he rarely sounds like anybody else. “Handel understands effect better than any of us,” wrote Mozart, one of his dedicated admirers. “When he chooses, he strikes like a thunderbolt.” Other qualified listeners concurred. When asked to name the all-time greatest composer, Beethoven exclaimed, “Handel—to him I bow the knee.” (Lying on his deathbed, Beethoven asked for a volume of Handel to console him.)

Handel’s oratorio Messiah dates from a crucial moment in his career. The work’s success in turn proved crucial to the history of the oratorio as a genre. While Handel composed his first oratorios during his early years in Rome, he did not write an oratorio in English until he composed Esther in 1718, by which time he had already achieved distinction as an opera composer. Italian opera would be his principal concern for 36 years, during which time he rode both the waves of success and the troughs of indifference that seem always to have marked the topsy-turvy world of lyric theater. By the late 1730s, however, Handel had his fill with the high-stress management of opera productions, and the opera he wrote for the 1740–41 season, Deidamia, was his last.

Just then he received an invitation to produce a series of concerts in Dublin in 1741, and the idea of a change of scenery appealed to him. He traveled from London to Dublin in mid-November 1741 and remained until August 13, 1742. The high point of Handel’s Dublin season was without a doubt the premiere of his new oratorio Messiah. He had composed it while still in London during the summer of 1741, over the course of about three weeks. His librettist, Charles Jennens, had been pressed into service to assemble a text for the new work. This he apparently did in the early summer of 1741, drawing creatively on Biblical passages from the Books of Isaiah, Haggai, Malachi, Matthew, Luke, Zechariah, John, Psalms, Lamentations, Hebrews, Romans, I Corinthians, and Revelation to create a loose story comprising historical narrative about the life of Jesus and reflections on his life by Christian believers. He organized his texts in three discrete sections, the first relating to the prophecy of Christ’s coming and the circumstances of his birth, the second to the vicissitudes of his life on earth, and the third to the events surrounding the resurrection and the promise of redemption. With the libretto in hand, Handel leapt into action on August 22. He finished the draft of Part One on August 28, of Part Two on September 6, and of Part Three on September 12—and then he took another two days to polish details on the whole score.

This prodigious pace was not exceptional for Handel, and it is no more than Romantic fantasy to view it (as it once was routinely) as a fever of divine inspiration peculiar to the composition of Messiah. At least some of Handel’s fluency can be attributed to the fact that Messiah borrows liberally (albeit ingeniously) from his earlier vocal works. As further evidence of Handel’s facility, the composer allowed himself about a week’s rest after finishing Messiah before embarking on his next oratorio, Samson, which he wrote in the relatively leisurely span of five weeks.

Handel’s Dublin season began auspiciously with performances of several earlier works—L’Allegro, Acis and Galatea, Esther, Alexander’s Feast—that paved the way for the excitement attending the premiere of Messiah. An open rehearsal on April 9 was followed by two official performances, on April 13 and June 3. The first performance was given as a benefit, organized with the assistance of the Charitable Musical Society, “For Relief of the Prisoners in the several Gaols, and for the Support of Mercer’s Hospital in St. Stephen’s street, and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inns Quay” (as The Dublin Journal announced it a couple of weeks in advance). After the open rehearsal The Dublin News Letter pronounced that the new oratorio “in the opinion of the best judges, far surpasses anything of that Nature, which has been performed in this or any other Kingdom.” The Journal concurred that it “was allowed by the greatest Judges to be the finest Composition of Musick that ever was heard, and the sacred Words as properly adapted for the Occasion.” It continued with a bit of advice for persons lucky enough to hold tickets for the official premiere, a matinee on April 13: “Many Ladies and Gentlemen who are well-wishers to the Noble and Grand Charity for which this Oratorio was composed, request it as a Favour, that the Ladies who honour this Performance with their Presence would be pleased to come without Hoops as it will greatly encrease the Charity, by making Room for more Company.” To which it added in a follow-up article: “The Gentlemen are desired to come without their Swords’, to increase audience accommodation yet further.” Messiah was an immense success, and its reputation spread quickly to London, which had to wait nearly a year to hear it, and where some controversy erupted over whether sacred texts had a place in an “entertainment.”

An Enduring Classic

The work gradually established itself as a classic. It was revived in London in 1745, again in 1749, and again in 1750—in this last year at both Covent Garden and as a benefit for the Foundling Hospital, which would make Messiah performances an Easter tradition. By the 1750s Messiah was becoming widely performed. For many of the early productions Handel revised his score, largely to fulfill the practical demands of differing soloists and instrumental ensembles, although partly (many argue) to reflect his changing conception of the piece. Surely no work in the standard repertory offers so vast a buffet of performing possibilities to choose from. From one version to the next, we find variations in which numbers are sung and in what order, which solo parts are assigned to which vocal soloist, even which competing versions of individual movements should be used. There are no easy answers, although performers should not discount that practical considerations are as important today as they were in Handel’s time.

In the 1780s England began giving free rein to presenting Messiah with ever-increasing masses of performers: 513 in Westminster Abbey in 1784, 616 the next year, and so on until the forces reached 1,068 musicians in 1791, when an ecstatic Franz Joseph Haydn happened to be in attendance. That marked a temporary climax in Messiah interpretation for Londoners, but by that time the Handel mania had begun to radiate out from London to Birmingham, Sheffield, York, and Manchester, all homes to major choral societies. The piece was also becoming famous elsewhere. It was an Englishman—Michael Arne, son of the composer (and Handel contemporary) Thomas Augustine Arne—who introduced Messiah to Germany, leading a performance in Hamburg in 1772. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach introduced it to Berlin audiences three years later, in a German translation, and in 1777 it reached Mannheim.

In other European countries, Handel remained a harder sell. The French viewed his music as simply not to their taste. Hector Berlioz dismissed Handel as “a barrel of pork and beer,” and Messiah didn’t get a French performance until 1873. The Italians seem to have lost track of Handel almost entirely once he completed his apprentice years in their country. America showed enthusiasm, as might be expected from a land still dominated by British cultural taste, and already in the 1770s and ’80s Messiah had become a staple of concert life in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, sometimes with the more modest American equivalent of the familiar massed forces of Britain.

Back to England. The grand Handel festivals at Westminster Abbey dropped off after 1791 but started again in 1834, presenting Handel spectacles to a new generation of listeners and sparking the Messiah tradition. Armed with cheaply printed scores or librettos, audiences devoutly followed the performances of their favorite choral societies. The Crystal Palace in London became the site of choice for Handel displays in the second half of the 19th century. In 1883 Sir Michael Costa stood on the podium before an ocean of 500 players and 4,000 singers. Behind him was an audience of 87,769. Thomas Edison’s phonograph had just been introduced, and somebody thought to record one of these mammoth Handel performances. The Edison cylinder made at the Crystal Palace on June 29, 1888, a similarly grandiose interpretation of the composer’s Israel in Egypt, became not only the first recording of classical music ever made, but also the first on-location recording. It had to be on location, of course, since 4,500 performers could not quite have fit into a recording studio.

This account hardly begins to suggest the scope of what must be classical music’s most beloved masterpiece. Messiah has captivated audiences since it was first heard, and it has been reinvented often since, made new to meet the exigencies of specific performers and evolving generations. Through all its changes it has remained pure, powerful, and moving: a classic.

—James M. Keller

Messiah

Text taken from the Scriptures by Charles Jennens (1700–73)

PART ONE

Sinfonia

Accompagnato (tenor)

Comfort ye, comfort ye, my people, saith your God:

Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplish’d, that her iniquity is pardoned.

The voice of Him that crieth in the wilderness: Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. (Isaiah 40:1–3)

Aria (tenor)

Ev’ry valley shall be exalted, and ev’ry mountain and hill made low, the crooked straight and the rough places plain. (Isaiah 40:4)

Chorus

And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed. And all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. (Isaiah 40:5)

Accompagnato (baritone)

Thus saith the Lord of Hosts:

Yet once a little while, and I will shake the heav’ns and the earth, the sea, and the dry land, all nations I’ll shake; and the desire of all nations shall come.

The Lord, whom ye seek, shall suddenly come to His temple; even the messenger of the Covenant whom ye delight in, behold,

He shall come, saith the Lord of Hosts. (Haggai 2:6–7, Malachi 3:1)

Aria (countertenor)

But who may abide the day of His coming, and who shall stand when He appeareth? For He is like a refiner’s fire. (Malachi 3:2)

Chorus

And He shall purify the sons of Levi, that they may offer unto the Lord an offering in righteousness. (Malachi 3:3)

Recitative (countertenor)

Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call His name Emmanuel, “God with us.” (Isaiah 7:14, Matthew 1:23)

Aria (countertenor) and Chorus

O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion get Thee up into the high mountain; O thou that tellest good tidings to Jerusalem lift up thy voice with strength, lift it up, be not afraid; say unto the cities of Judah: Behold your God!

Arise, shine, for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee. (Isaiah 40:9, 40:1)

Accompagnato (baritone)

For behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the people: but the Lord shall arise upon thee, and His glory shall be seen upon thee.

And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising. (Isaiah 60:2–3)

Aria (baritone)

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light. And they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined. (Isaiah 9:2)

Chorus

For unto us a Child is born, unto us a Son is given and the government shall be upon His shoulder, and His name shall be called: Wonderful Counsellor, The Mighty God, The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace! (Isaiah 9:6)

Pifa (orchestra)

Recitative (soprano)

There were shepherds abiding in the field,

keeping watch over their flock by night. (Luke 2:8)

Accompagnato (soprano)

And lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them,

and the glory of the Lord shone round about them,

and they were sore afraid. (Luke 2:9)

Recitative (soprano)

And the angel said unto them: Fear not; for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.

For unto you is born this day, in the city of David, a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. (Luke 2:10–11)

Accompagnato (soprano)

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heav’nly host, praising God, and saying:

(Luke 2:13)

Chorus

“Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth,

good will toward men.” (Luke 2:14)

Aria (soprano)

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout, O daughter of Jerusalem! Behold, thy King com’th unto thee.

He is the righteous Saviour, and He shall speak peace unto the heathen. (Zechariah 9:9–10)

Recitative (countertenor)

Then shall the eyes of the blind be open’d, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then shall the lame man leap as an hart, and the tongue of the dumb shall sing. (Isaiah 35:5–6)

Aria (countertenor and soprano)

He shall feed His flock like a shepherd: and He shall gather the lambs with His arm, and carry them in His bosom, and gently lead those that are with young.

Come unto Him, all ye that labour, come unto Him all ye that are heavy laden, and He will give you rest.

Take His yoke upon you, and learn of Him; for He is meek and lowly of heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls.

(Isaiah 40:11, Matthew 11:28–9)

Chorus

His yoke is easy, and His burden is light. (Matthew 11:30)

Intermission

PART TWO

Chorus

Behold the Lamb of God, that taketh away the sin of the world.

(John 1:29)

Aria (countertenor)

He was despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief.

He gave His back to the smiters, and His cheeks to them that plucked off the hair: He hid not His face from shame and spitting. (Isaiah 53:3, John 1:6)

Chorus

Surely He hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows;

He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities; the chastisement of our peace was upon Him.

(Isaiah 53:4–5)

Chorus

And with His stripes we are healed. (Isaiah 53:5)

Chorus

All we, like sheep, have gone astray,

we have turned ev’ry one to his own way;

and the Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all. (Isaiah 53:6)

Accompagnato (tenor)

All they that see Him laugh Him to scorn;

they shoot out their lips, and shake their heads, saying:

(Psalm 22:7)

Chorus

He trusted in God that He would deliver Him;

let Him deliver Him, if He delight in Him. (Psalm 22:8)

Accompagnato (tenor)

Thy rebuke hath broken His heart; He is full of heaviness;

He looked for some to have pity on him, but there was no man, neither found He any to comfort Him. (Psalm 69:20)

Aria (tenor)

Behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto His sorrow.

(Lamentations 1:12)

Accompagnato (soprano)

He was cut off out of the land of the living: for the transgression of Thy people was He stricken. (Isaiah 53:8)

Aria (soprano)

But Thou didst not leave His soul in hell; nor didst Thou suffer thy Holy One to see corruption. (Psalm 16:10)

Chorus

Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of Glory shall come in.

Who is this King of Glory?

The Lord of Hosts: He is the King of Glory.

(Psalm 24:7–10)

Aria (soprano)

How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things. (Romans 10:15)

Aria (baritone)

Why do the nations so furiously rage together, and why do the people imagine a vain thing?

The kings of the earth rise up, and the rulers take counsel together against the Lord and His anointed. (Psalm 2:1–2)

Chorus

Let us break their bonds asunder,

and cast away their yokes from us. (Psalm 2:3)

Recitative (tenor)

He that dwelleth in heaven shall laugh them to scorn,

the Lord shall have them in derision. (Psalm 2:4)

Aria (tenor)

Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron;

Thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel. (Psalm 2:9)

Chorus

Hallelujah, for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.

The Kingdom of this world is become the Kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ; and He shall reign forever and ever.

King of Kings, and Lord of Lords. Hallelujah!

(Revelation 19:6, 11:5, 19:16)

PART THREE

Aria (soprano)

I know that my Redeemer liveth,

and that He shall stand at the latter day upon the earth:

And tho’ worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God. For now is Christ risen from the dead, the first fruits of them that sleep. (Job 19, 25–26, I Corinthians 15:20)

Chorus

Since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection

of the dead.

For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.

(I Corinthians 15:21–22)

Accompagnato (baritone)

Behold, I tell you a mystery: we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be chang’d, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. (I Corinthians 15:51–52)

Aria (baritone)

The trumpet shall sound and the dead shall be rais’d incorruptible, and we shall be chang’d.

(I Corinthians 15:52)

Chorus

Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by His blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing.

Blessing, and honour, glory, and pow’r be unto Him that sitteth upon the throne and unto the Lamb for ever and ever.

(Revelation 5:9, 12–13)

Chorus

Amen.

About the Artists

Stephen Stubbs

Stephen Stubbs won a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording and maintains a busy calendar as a guest conductor specializing in Baroque opera and oratorio. He began his career as an opera conductor at the 1987 Bruges Festival, which led to the founding of the ensemble Tragicomedia. Since 1997 he has codirected opera productions at the biannual Boston Early Music Festival, where he serves as artistic codirector. BEMF has been nominated for six Grammy Awards and won a Grammy for their recording of Charpentier’s La descente d’Orphée aux enfers. Stubbs is also the founding director of Pacific MusicWorks, a touring company with a core group of musicians who have worked together for more than 15 years.

Stubbs has conducted Handel’s Messiah with the Seattle Symphony, Houston Symphony, Alabama Symphony, Edmonton Symphony, and Symphony Nova Scotia. Other guest conducting appearances include the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Baroque Chamber Orchestra of Colorado, Musica Angelica, and Early Music Vancouver. On the opera stage, he has made multiple appearances with Opera Omaha, as well as with Seattle Opera, Los Angeles Opera, and Dutch National Opera. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Amanda Forsythe

Amanda Forsythe is a regular soloist with Baroque ensembles and festivals including Les Talens Lyriques, Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra, Boston Early Music Festival, Handel and Haydn Society, Boston Baroque, Tafelmusik, Apollo’s Fire, Opera Prima, Pacific Musicworks, Early Music Vancouver, and Philharmonia Baroque. This season she performs with the Chicago Symphony, Royal Northern Sinfonia, Victoria Symphony, Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Boston Baroque, Tucson Baroque Festival, and Boston Early Music Festival. In recent seasons she has also appeared with the Boston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Orchestra Sinfonica Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Moscow Philharmonic, Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano, Academy of Ancient Music, St. Louis Symphony, Music of the Baroque, and Lucerne Symphony Orchestra. She makes her San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Forsythe sang Euridice on the recording of Charpentier’s La descente d’Orphée aux enfers with the Boston Early Music Festival that won a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording. Her discography includes more than 25 albums and DVDs, many of them premiere recordings. Forthcoming discs include Handel’s Roman Cantatas, Pergolesi’s La serva padrona, and a solo Telemann album.

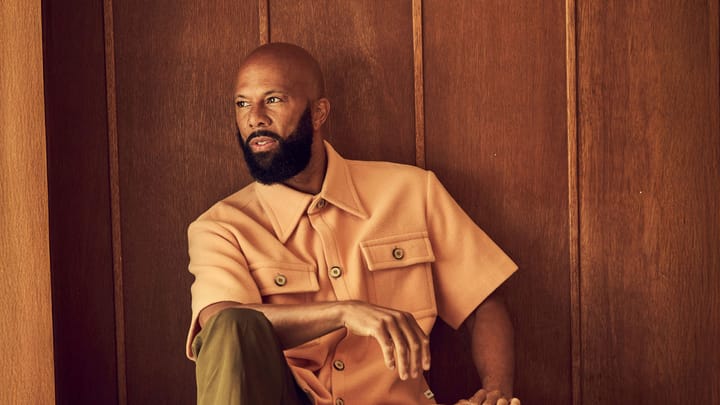

John Holiday

Highlights of John Holiday’s 2024–25 season include roles at Boston Lyric Opera, Berlin Comic Opera, Bavarian State Opera, and a tour with the English Concert to Carnegie Hall and the Barbican. He also performs with the New Jersey Symphony, Apollo Chamber Players, gives a solo recital at Wolf Trap, and recently appeared on NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

In recent seasons, Holiday has appeared with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, Glimmerglass Festival, Wolf Trap Opera, Handel and Haydn Society, Dutch National Opera, and Arizona Opera. In addition to concerts and recitals, he has curated The John Holiday Experience to showcase his affinity for many different styles including classical, pop, jazz, and R&B.

Holiday has been the recipient of numerous awards including the 2017 Marian Anderson Vocal Award; the 2014 Richard Tucker Foundation’s Sara Tucker Award; and first place wins at the 2013 Gerda Lissner International Vocal Competition, 2012 Sullivan Foundation Awards, and 2011 Dallas Opera Guild Vocal Competition. He was selected among WQXR’s “20 for ’20 Artists to Watch,” nominated for “Newcomer of the Year” by the German magazine Opernwelt, and listed as one of Yerba Buena Center for the Arts’ 100 honorees for 2018.

Aaron Sheehan

Aaron Sheehan made his professional operatic debut with the Boston Early Music Festival in the 2005 world premiere staging of Mattheson’s Boris Gudenow, and went on to further roles with BEMF in Lully’s Psyché; Charpentier’s Actéon; Monteverdi’s Orfeo, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, and L’incoronazione di Poppea; Steffani’s Orlando; Desmarest’s Circé; and Handel’s Acis and Galatea.

Sheehan appears on more than 35 recordings, including Handel’s Acis and Galatea with Boston Early Music Festival, Rameau’s Le Temple de la Gloire and Handel’s Saul with Philharmonia Baroque, and Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria with Boston Baroque. He sang the title role in BEMF’s recording of Charpentier’s La Descente d’Orphée aux enfers, which won Best Opera Recording at the 2015 Grammy Awards.

Recent appearances include the Seattle Symphony, Armenian Philharmonic, Smithsonian Museum, American Bach Soloists, Handel and Haydn Society, Boston Baroque, and National Symphony Orchestra of Peru. He has also been heard with Pacific Music Works, Blue Heron Choir, Bach Collegium San Diego, Paul Hillier’s Theater of Voices, Royal Opera at Versailles, Tanglewood Music Festival, New Zealand Festival of the Arts, San Francisco Early Music Festival, and Vancouver Early Music Festival. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Douglas Williams

Douglas Williams has appeared in leading opera roles including Figaro in Le nozze di Figaro with the Milwaukee Symphony, Don Giovanni with Opera Atelier, and Nick Shadow in The Rake’s Progress with the Munich Philharmonic. Recent highlights include the premiere of a new work by Matthew Barnson with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and a debut recording of Henry Desmarest’s Circé with the Boston Early Music Festival. In concert, he has appeared with the Berlin Philharmonic, NDR Radio Philharmonic, Houston Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, Detroit Symphony, National Symphony, and Nashville Symphony. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Williams has also been cast in opera productions by choreographers Mark Morris and Sasha Waltz, and he is currently creating a choreographic Die schöne Müllerin for himself and three dancers. In chamber music, he has sung with Igor Levit and the Jack Quartet at the Tanglewood Festival, with the Signal Ensemble in the world premiere of Charles Wuorinen’s It Happens Like This, and recently as a guest recitalist with the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society. He trained at the New England Conservatory and Yale School of Music.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

Under Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

SOPRANOS

Morgan Balfour*

Arlene Boyd

Laura Canavan

Phoebe Chee*

Tonia D’Amelio*

Amy Foote*

Cara Gabrielson*

Susanna Gilbert

Julia Hall

Ashley Hecht

Elizabeth Heckmann

Becky Lau

Kyounghee Lee

Ellen Leslie*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Natalia Salemmo*

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Sigrid Van Bladel

Lauren Wilbanks

ALTOS

Terry A. Alvord*

Celeste Camarena

Enrica Casucci

Nicole Daamen

Shauna Fallihee*

Stacey L. Helley

Amy L. Hespenheide

Kelsey M. Ishimatsu Jacobson

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen Josaitis

Gretchen Klein

Katherine M. Lilly

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Kimberly J. Orbik

Leandra Ramm*

Linda J. Randall

Celeste Riepe

Dr. Meghan Spyker*

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

TENORS

Carl A. Boe

Todd Bradley

Seth Brenzel*

Daniel J. Costa

Thomas L. Ellison

Elliott JG Encarnación*

Sam Faustine*

Kevin Gibbs*

Kevin Gino*

Alec Jeong

James Lee

Benjamin Liupaogo*

Joachim Luis*

Justin Farrell Marsh

Andrew P. McIver

Jack O’Reilly

Ryan S. Peterson

John A. Vlahides

Jack Wilkins*

Weichen Winston Yin

Jakob Zwiener

BASSES

Josh Bozich

Sean Brooks

Phil Buonadonna

Robert Calvert

Adam Cole*

Noam Cook

James Radcliffe Cowing III

Malcolm Gaines

Harlan J. Hays*

Rob Lloyd Huber

Tim Marson

Richard Mix*

James Monios*

Clayton Moser*

Julian Nesbitt

Chung-Wai Soong*

Storm K. Staley

Michael Taylor*

Connor Tench

Nick Volkert*

Goangshiuan Shawn Ying

Jenny Wong

Chorus Director

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist

*Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists