In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, March 23, 2025, at 7:30pm

Lahav Shani conducting

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

Tzvi Avni

Prayer (1961)

Max Bruch

Kol Nidrei, Opus 47 (1880)

Haran Meltzer cello

Leonard Bernstein

Halil (1981)

Guy Eshed flute

Intermission

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64 (1888)

Andante–Allegro con anima

Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza

Valse: Allegro moderato

Finale: Andante maestoso–Allegro vivace–

Moderato assai e molto maestoso–

Presto–Molto meno mosso

This concert is generously made possible by Nellie and Max Levchin.

The Music for Families Series is supported by

Program Notes

Prayer

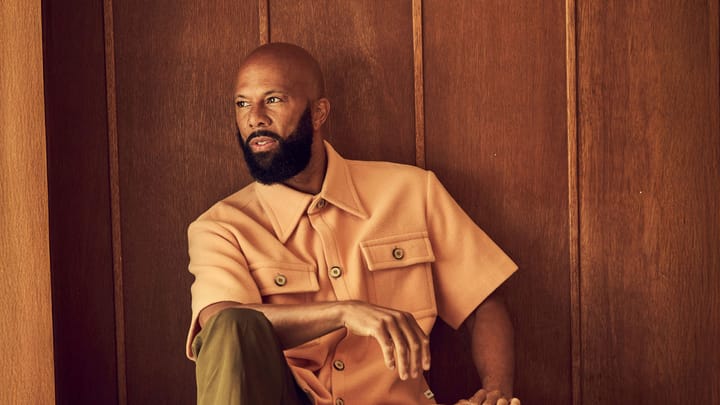

Tzi Avni

Born: September 2, 1927, in Saarbrücken, Germany

Work Composed: 1961

Instrumentation: strings

Duration: About 10 minutes

Tzi Avni was born in 1927 in Saarbrücken, Germany, then under French and British administration following the Treaty of Versailles. In 1935, shortly after the region was reclaimed by Nazi Germany, he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine with his parents. He first studied at the Music Academy in Tel Aviv and Tel Aviv Music Academy, and went on to Columbia University and the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied with Aaron Copland and Lukas Foss.

From 1971 to 2015, Avni taught theory and composition at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. He founded and directed the Academy’s electronic music studio, and in 1976 was appointed professor of theory and composition.

Now in his 10th decade, he is a professor emeritus at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. In 2001 he was awarded the Israel Prize for music.

Avni’s early works were influenced by the Eastern Mediterranean style that was dominant in Israel’s art music scene in those years, characterized by dance rhythms and tonal-modal elements in harmony and melody. In the beginning of the 1960s, his compositions began to be influenced by his interest in electronic music and the more radical approaches he met during his stay in the United States. By the mid-’70s, his works took on a new approach towards more tonal elements.

In his own program note for Prayer, Avni writes:

Prayer for strings was composed in 1961. After re-working it in 1969, I dedicated it in its new form to Fannie and Max Targ of Chicago, who contributed in so many ways towards the fostering of music in Israel.

The work is composed of three main sections: a meditative, prayer-like mood pervades the first and third, whereas in the middle section the flow of the movement increases, transforming the prayer into an ecstatic dance. The texture of this section is woven out of rhythmic martellato passages alternating with others of polyphonic-fugal nature. Interposed here are also short passages which revert to the quieter atmosphere of the prayer. The hushed ending of the work brings with it a feeling of calm and reconciliation.

Prayer was first performed in Israel in 1962 by the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra of the Israel Broadcasting Authority, conducted by Gary Bertini. Since then it has been performed many times in Israel and abroad by orchestras such as the Israel Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Budapest Festival Orchestra, and more.

Adapted from material provided by Tzi Avni.

Kol Nidrei, Opus 47

Max Bruch

Born: January 6, 1838, in Cologne

Died: October 2, 1920, in Berlin

Work Composed: 1880

Instrumentation: solo cello, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, harp, and strings

Duration: About 10 minutes

Kol Nidrei is one of the first works Bruch composed after assuming the position of principal conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. Written in 1880, the piece was commissioned from the composer by Liverpool’s Jewish community. Bruch, a Protestant, had long been interested in folk music from various cultures, including Jewish music. He was not the only one, as this period saw many composers who, in addition to the unique music of their own nationalities, showed interest in the music of other cultures and minorities. Composers from central Europe created works influenced by Spanish, Turkish, Romani, and Jewish music.

Kol Nidrei for cello and orchestra is a “mashup” combination of two sections, each based on a different Jewish source. Bruch got to know these sources a few years before composing the piece, when he was an independent musician in Berlin. The first section, in minor key, is based on the Ashkenazi tune of Kol Nidrei (All Vows), a prayer sung on Yom Kippur eve. The strings, followed by a few wind instruments, play a short introduction preparing the ground for the soloist who joins with the moving melody of the prayer. The melody opens with a descending semitone, a highly expressive gesture associated with sighing. This gesture is also known as the pianto (crying) motive. This section has an introverted atmosphere; the cello is accompanied solely by the strings, which play a static part, allowing interpretative freedom for the soloist, while the rest of the orchestra remains silent. Three plucks heard by the harp, playing now for the first time, end the first section and prepare us for the next, harmonically and emotionally.

The second section opens with a great light; the entire orchestra (except for the timpani) enters in a major key. High pitches in the woodwinds and a constant arpeggio movement in the harp and violins color the music in bright shades. The theme of this section is based on the middle section of the song “Oh! weep for those that wept on Babel’s stream,” composed by the Jewish-British 19th-century composer Isaac Nathan. Texts of the original melodies disappear from Bruch’s concert music, in which only the music remains. The Jewish musicologist Abraham Zevi Idelsohn wrote that “Bruch displayed a fine art, masterly technique and fantasy, but not Jewish sentiments. It is not a Jewish Kol-Nidre which Bruch composed.” Is this a completely universal piece, or perhaps, something of the particular meanings of the original texts remains?

—Oded Shnei-Dor

Halil

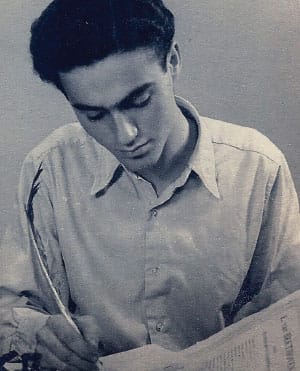

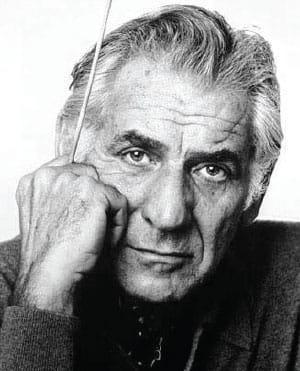

Leonard Bernstein

Born: August 25, 1918, in Lawrence, Massachusetts

Died: October 14, 1990, in New York

Work Composed: 1981

Instrumentation: solo flute, piccolo (doubling alto flute), timpani, percussion (vibraphone, snare drums, bass drum, suspended cymbals, gongs, glockenspiel, xylophone, triangles, chimes, tom-toms, cymbals, tam-tam, whip, and woodblocks), harp, and strings

Duration: About 16 minutes

Leonard Bernstein was a world-renowned musician throughout his entire adult life. He served as music director of the New York Philharmonic and conducted the world’s major orchestras, recording hundreds of performances. His books and the televised Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic established him as a leading educator.

Bernstein’s compositions include Jeremiah, The Age of Anxiety, Kaddish, Serenade, Five Anniversaries, Mass, Chichester Psalms, Slava!, Songfest, Divertimento for Orchestra, Missa Brevis, Arias and Barcarolles, Concerto for Orchestra, and A Quiet Place. He also composed for the Broadway musical stage, creating masterpieces such as On the Town, Wonderful Town, Candide, and the immensely popular West Side Story. In addition to the West Side Story collaboration, Bernstein worked with choreographer Jerome Robbins on three major ballets: Fancy Free, Facsimile, and Dybbk. Bernstein was the recipient of many honors, including the Antoinette Perry Tony Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Theater, 11 Emmy Awards, the Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award, and the Kennedy Center Honors.

About Halil, Bernstein wrote:

This work is dedicated “To the Spirit of Yadin and to his Fallen Brothers.” The reference is to Yadin Tanenbaum, a 19-year-old Israeli flutist who, in 1973, at the height of his musical powers, was killed in his tank in the Sinai. He would have been 27 years old at the time this piece was written.

Halil (the Hebrew word for “flute”) is formally unlike any other work I have written, but is like much of my music in its struggle between tonal and non-tonal forces. In this case, I sense that struggle as involving wars and the threat of wars, the overwhelming desire to live, and the consolations of art, love and the hope for peace. It is a kind of night-music which, from its opening 12-tone row to its ambiguously diatonic final cadence, is an ongoing conflict of nocturnal images: wish-dreams, nightmares, repose, sleeplessness, night-terrors and sleep itself, Death’s twin brother.

I never knew Yadin Tanenbaum, but I know his spirit.

Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes.

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64

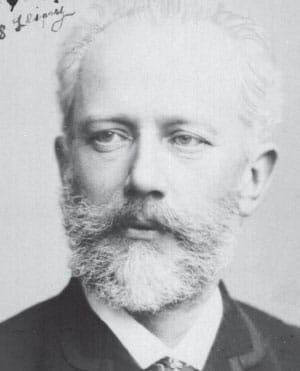

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1888

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 50 minutes

Tchaikovsky’s feelings about the Fifth Symphony blew hot and cold, as they did about so many of his works: “I am dreadfully anxious to prove not only to others, but also to myself, that I am not yet played out as a composer. . . . The beginning was difficult; now, however, inspiration seems to have come. . . . I have to squeeze it from my dulled brain. . . . It seems to me that I have not blundered, that it has turned out well.”

Ten years had gone by since the Fourth Symphony, ten years in which Tchaikovsky’s international reputation was consolidated. The Fourth had been the symphony of triumph over fate and was in that sense, admittedly, an imitation of the Beethoven Fifth. For Tchaikovsky’s own Fifth we have nothing as explicitly revealing as the correspondence in which he set out the program of the Fourth for his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck. There is, however, a notebook page dated April 15, 1888, which is about a month before Tchaikovsky began work on his new symphony, and here he outlines a scenario for the first movement: “Intr[oduction]. Complete resignation before Fate, or, which is the same, before the inscrut[able] predestination of Providence. Allegro. (1) Murmurs of doubt, complaints, reproaches against XXX. (2) Shall I throw myself in the embraces of faith??? A wonderful program, if only it can be carried out.”

This is not helpful. Furthermore, we have no idea whom or what Tchaikovsky meant by “XXX.” Some writers have suggested that it might be what he usually referred to in his diary as Z or THAT, his homosexuality, but in this context that makes little sense. To pursue the verbal plan as it appears in the notebook through the first movement as he finally composed it is fruitless. Clearly, though, the theme with which the clarinets in their lowest register begin the symphony has a function other than its musical one. It will recur as a catastrophic interruption of the second movement’s love song, as an enervated ghost that approaches the languid dancers of the waltz, and—in a metamorphosis that is perhaps the symphony’s least convincing musical and expressive gesture—in majestic and blazing E-major triumph.

The Music

Tchaikovsky begins the Fifth with a portentous introduction. The tempo is fairly slow, the colors (low clarinets and low strings) are dark. The theme, suggestive here of a funeral march, sticks easily in the memory. Let us call it the Fate theme. Its rhythm is distinctive enough to be recognizable by itself, and that will prove useful. The introduction gradually subsides, coming to a suspenseful halt.

When the main part of the first movement begins, the tempo is quicker and the theme is new; nonetheless, we hear a connection because the alternating chords of E minor and A minor in the first 12 measures are the very ones with which the Fate theme was harmonized. Clarinet and bassoon play the theme, a melancholy and graceful song.

Tchaikovsky boils this up to a fortississimo climax, then goes without break into a new, anguished theme for strings with characteristic little punctuation marks for the woodwinds. With these materials he builds a strong, highly energized movement, which, however, vanishes in utter darkness.

In 1939, Mack David, Mack Davis, and André Kostelanetz came out with a song called “Moon Love.” It had a great tune—by Tchaikovsky. It is the one you now hear the French horn play, better harmonized and with a better continuation. When he has built some grand paragraphs out of the horn melody and its various continuations, Tchaikovsky speeds up the music still more, at which point the clarinet introduces an entirely new and wistful phrase, which is picked up and carried further by the bassoon and then the several string sections. The spinning out of this idea is brutally interrupted by the Fate theme. The music stops in shocked silence. Great pizzicato chords restore order, the violins take up the horn melody, which other instruments decorate richly. Once again, there is a great cresting, and once again the Fate theme intervenes. This time there is no real recovery. With a final appearance of what was originally the oboe’s continuation of the horn melody, the movement sinks to an exhausted close. “Resignation before Fate”?

Functioning in the place of a scherzo, Tchaikovsky gives us a graceful, somewhat melancholic waltz. Varied and inventive interludes separate the returns of the initial melody, and just before the end the Fate theme ghosts softly over the stage.

The Finale begins with the Fate theme, but heard now in a quietly sonorous E major. This opening corresponds to the introduction of the first movement. This time, though, the increase in tempo is greater, and the new theme is possessed by an almost violent energy. A highly charged sonata form movement unfolds. Toward the end of the recapitulation, Fate reappears, now just as a rhythm. This leads to an exciting and suspenseful buildup, whose tensions are resolved when the Fate theme marches forward in its most triumphant form—in major, fortissimo, broad, majestic. The moment of suspense just before this grand arrival has turned out to be a famous audience trap. People who haven’t really been listening but have noticed that the music has stopped are liable to begin their applause at this point. After the Fate theme has made its splendid entrance, the music moves forward into a headlong Presto, broadening again for the rousing final pages.

—Michael Steinberg

About the Artists

Lahav Shani

Lahav Shani, music director of the Israel Philharmonic, has been chief conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic since 2018 and was previously principal guest conductor of the Vienna Symphony. In February 2023, the Munich Philharmonic appointed him as their new chief conductor, starting from September 2026. His close relationship with the Israel Philharmonic begain in 2007, when he performed Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto under the baton of Zubin Mehta, and continued in 2010, when Mehta invited him to join the Israel Philharmonic on tour as pianist, assistant conductor, and double bass player. In 2013, after winning the Gustav Mahler International Conducting Competition in Bamberg, the orchestra invited him to step in to conduct their season opening concerts.

Shani has also appeared with the Vienna Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Symphony, London Symphony, La Scala Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and Philharmonia Orchestra.

Born in Tel Aviv in 1989, Shani began his piano studies aged six before continuing at the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music. He went on to study at the Hanns Eisler Academy of Music in Berlin, and was mentored by Daniel Barenboim.

Israel Philharmonic

The Israel Philharmonic is one of Israel’s oldest and most influential cultural institutions. Since 1936, it has dedicated itself to presenting the world’s greatest music to audiences in Israel and around the world. Founded by the Polish violinist Bronisław Huberman, the Israel Philharmonic represents the fulfillment of his dream “to unite the desire of the country for an orchestra with the desire of the Jewish musicians for a country.” Huberman persuaded first-chair musicians of Eastern European and German orchestras who had lost their jobs as a result of Nazism to immigrate to Palestine. In doing so, Huberman created an “orchestra of soloists,” which continues to act as a dynamic global community for musicians from across the world. Huberman invited Arturo Toscanini to conduct the opening concert, performed at the Levant Fair in Tel Aviv on December 26, 1936.

The Israel Philharmonic is Israel’s premier cultural ambassador and travels extensively throughout the world, particularly to countries where there is little or no Israeli representation. In December 2022, the Israel Philharmonic performed a historic concert in Abu Dhabi at the invitation of the Abu Dhabi Ministry of Culture, celebrating the Abraham Accords. Other historical visits include the orchestra’s first tour to Russia in April 1990 and the first tour to India in December 1960. The orchestra performs in the most important venues and festivals in Europe, the United States, South America, China, and Japan. The orchestra gives more than 100 performances each year in Israel, where concert series are presented in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa.

In 1969, Zubin Mehta was appointed music advisor to the IPO and in 1977 he became its music director. Mehta retired in October 2019 and the IPO named him music director emeritus. Lahav Shani became music director in the 2020–21 season.

The Israel Philharmonic’s 2025 US tour is underwritten by American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic and sponsored by Pfizer.

Exclusive Tour Management and Representation: Opus 3 Artists

Haran Meltzer

Haran Meltzer is principal cello of the Israel Philharmonic. He won first prizes in the Aviv Competition, Davidov Competition, and Gabrielli Competition, and has received scholarships from the America-Israel Cultural Foundation and the Zfunot Tarbut Foundation. As a chamber musician, he collaborated with Itzhak Perlman, among many other prominent musicians. Meltzer studied at the Kfar Saba Conservatory, Israel Conservatory of Music, and Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin. He plays on a cello loaned by the Israel Philharmonic and a bow loaned to him by the America-Israel Cultural Foundation.

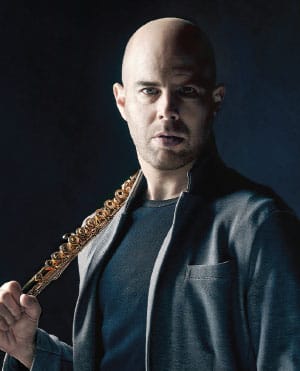

Guy Eshed

Guy Eshed is principal flutist of the Israel Philharmonic and has been principal of several other orchestras internationally. After his military service, he was principal in the Haifa Symphony Orchestra and since 2001 has been principal of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, directed by Daniel Barenboim. He has received scholarships from the America-Israel Cultural Foundation and received a special grant of excellence from the Toepfer Foundation in Hamburg.

IPO Management: Yuval Shapiro (Chair), Jonathan Gertner, and Boaz Meirovitch

Secretary General: Yair Mashiach

Artistic Director: Alisa Meves

Musicians’ Council: Sharon Cohen (Chair), Jonathan Gertner, Noam Massarik, Boaz Meirovitch, Dan Moshayev, Gili Radian-Sade, Hagai Shalom, Yuval Shapiro, and Ari Þór Vilhjálmsson

Orchestra Personnel Manager: Michal Bach

Asst. Personnel Managers: Yael Glazer and Katya Dashkov Totev

Inspector: Hadar Cohen

Librarian: Akkad Izre’el

Operational and Stage Management: Amit Cohen and Denis Rubin

Project Manager: Iris Abramovici

Artistic Operations Department: Nitzan Vardi

Marketing Manager: Yael Yardeni-Sela

Marketing: Liz Fisher and Ohad Dan

For Opus 3 Artists

Robert Berretta, Managing Director

Benjamin Maimin, Chief Operating Officer

Jemma Lehner, Associate Manager

Miles Bentley, Administrative Assistant

For the Israel Philharmonic Tour

Leonard Stein, Consulting Producer

Peter Katz, Touring Coordinator

John Pendleton, Company Manager

Sarah Vardigans, Advance Company Manager

Carol Patella, Assistant Company Manager

Don Irving, Stage Manager

Israel Philharmonic

First Violins

Ilya Konovalov, Concertmaster

Canada Concertmaster Chair

Dumitru Pocitari*, Concertmaster

Canada Concertmaster Chair

Saida Bar-Lev, Assistant Concertmaster

Polina Yehudin, Acting Assistant Concertmaster

Daniel Aizenshtadt

Nitzan Canetty

Sharon Cohen

Adelina Grodsky

Genadi Gurevich

Lev Iomdin

Andrei Kuznetsov

Eleonora Lutsky

Solomon Markman

Shai Nakash

Gilad Rivkin

Anna Siegreich

Yelena Tishin

Drorit Valk

Nasif Francis, The Academy Program

Second Violins

Yevgenia Pikovsky, Principal

Ari Þór Vilhjálmsson, Principal

Amnon Valk, Assistant Principal

Liora Altschuler

Alina Boyarkina

Hadar Cohen

Alexander Dobrinsky

Anna Doulov

Shmuel Glaser

Yuki Ishizaka

Sivann Maayani

Tomoko Malkin

Asaf Maoz

Marianna Povolotzky

Avital Steiner Tuneh

Olga Stern

Albatina Rachmanina,

The Academy Program

Violas

Miriam Hartman, Principal

Dmitri Ratush, Principal

Amir van der Hal, Assistant Principal

Lotem Beider Ben Aharon

Jonathan Gertner

Yeshaayahu Ginzburg

Vladislav Krasnov

Sofia Lebed

Klara Nosovitsky

Matan Noussimovitch

Evgenia Oren

Gili Radian-Sade

Inbar Segev Susar, The Academy Program

Cellos

Haran Meltzer, Principal

Lia Chen Perlov, Principal

Gal Nyska, Assistant Principal

Dmitri Golderman

Iakov Kashin

Linor Katz

Enrique Maltz

Kirill Mihanovsky

Felix Nemirovsky

Tamar Deutsch, The Academy Program

Basses

Nir Comforty, Assistant Principal

Brad Annis

Uri Arbel*

Nimrod Kling

Noam Massarik

David Segal

Kirill Sobolev

Omry Weinberger

Harp

Sophie Baird-Daniel, Principal

Flutes

Guy Eshed, Principal

Tomer Amrani, Principal

Boaz Meirovitch

Lior Eitan

Piccolo

Lior Eitan

Oboes

Dudu Carmel, Principal

Lior Michel Virot, Principal

Dmitry Malkin

Tamar Narkiss-Meltzer

English Horn

Dmitry Malkin

Clarinets

Ron Selka, Principal

Yevgeny Yehudin, Principal

Rashelly Davis

Jonathan Hadas

Clarinets in E-flat

Ron Selka

Yevgeny Yehudin

Bass Clarinet

Jonathan Hadas

Bassoons

Daniel Mazaki, Principal

Uzi Shalev, Assistant Principal

Gad Lederman*

Yael Falik

Gal Varon

Contrabassoons

Yael Falik

Gal Varon

Trumpets

Yigal Meltzer, Principal

Zachary Silberschlag

Eran Reemy

Yuval Shapiro

Horns

Dalit Segal, Assistant Principal

Michael Slatkin, Assistant Principal

Yoel Abadi

Michal Mossek

Gal Raviv

Hagai Shalom

Trombones

Nir Erez, Principal

Tal Ben Rei, Assistant Principal

Micha Davis

Bass Trombone

Micha Davis

Tuba

Itai Agmon, Principal

Timpani

Dan Moshayev, Principal

Ziv Stein, Assistant Principal

Percussion

Ziv Stein, Principal

Alexander Nemirovsky

Ayal Rafiah

Principal Librarian

Tal Rockman

Assistant Principal Librarian

Akkad Izre’el

Batya Frenklakh

Operational & Stage Manager

Amit Cohen

Technical Assistants

Denis Rubin

Noam Polonsky