In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, November 10, 2024, at 7:30pm

Itzhak Perlman violin

Emanuel Ax piano

Jean-Yves Thibaudet piano

Juilliard String Quartet

Areta Zhulla violin

Ronald Copes violin

Molly Carr viola

Astrid Schween cello

Jean-Marie Leclair

Sonata for Two Violins in E minor, Opus 3, no.5 (ca. 1734)

Allegro ma poco

Andante (Gavotta, gratiosa)

Presto

Itzhak Perlman violin

Areta Zhulla violin

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493 (1786)

Allegro

Larghetto

Allegretto

Itzhak Perlman violin

Molly Carr viola

Astrid Schween cello

Emanuel Ax piano

Intermission

Ernest Chausson

Concert in D major, Opus 21 (1891)

Décidé

Sicilienne

Grave

Finale

Itzhak Perlman violin

Jean-Yves Thibaudet piano

Juilliard String Quartet

Presenting Sponsor of the Great Performers Series

Program Notes

Sonata for Two Violins in E minor, Opus 3, no.5

Jean-Marie Leclair

Born: May 10, 1697 in Lyon

Died: October 22, 1764, in Paris

Work Composed: ca. 1734

On the modest roster of concert composers who met their end through homicide, Jean-Marie Leclair holds a place of continuing intrigue because for 260 years his demise has remained an open case in the files of the Prefecture of Police of Paris.

He began life innocently enough, mastering the arts of violin-playing, dancing, and lace-making in his native Lyon. He surfaced in Paris in 1723, and the publication of his first set of violin sonatas that year earned him accolades, although they were judged to be immensely difficult: one writer described them as “a sort of musical algebra capable of rebuffing the most courageous musicians.” A peripatetic career ensued—Turin, London, Kassel, Amsterdam, back to Paris, where he settled for good in about 1745. There he produced an opera in 1746—it met with slight success—and served as music director for the private opera theatre of the Duc de Gramont. He published his Opus 13, the final collection of his lifetime, in 1753.

Toward the end of this span, Leclair’s life was not headed in a good direction. In about 1758 he separated from his second wife, Louise, whom he had married in 1730. He set up housekeeping on his own at a small home in an unsavory neighborhood, and it was there that he was found, thrice stabbed and lying in a pool of blood, early on the morning of October 23, 1764. The police narrowed the short-list to three suspects: the gardener who discovered the body; the composer’s nephew, with whom he had a hostile relationship and who resented that his uncle failed to help promote his career as a violinist; and Louise, who inherited his estate and relieved her own financial crisis by auctioning off his possessions. The musicologist Neal Zaslaw, writing in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, avers that “the murder is often said to be shrouded in mystery, but the evidence (in the French Archives Nationales) is so clearly against the nephew . . . that the only remaining mystery is that he was never brought to trial.”

Although Leclair’s life and death inevitably attract unusual interest, what he accomplished as a composer was far from negligible, although, as Zaslaw remarks, “his remarkably consistent style was as advanced in 1723 as it was outmoded in 1753.” As a violinist, he was noted for left-hand mastery; forays into high positions and extended double-stopped passages are typical in his writing. He was honored as a paragon of the French style of string playing, and when, in the late 1720s, he appeared in a sort of musical duel with the also vaunted violinist Pietro Locatelli, he was judged to play “like an angel” with a singing tone, while the Italian was said to play “like the devil” with a technique that stressed fireworks over timbral finesse.

Apart from his opera, Leclair’s published catalogue was given over almost entirely to works for violin. His Opus 3, a group of six duo sonatas, was printed around 1734, when French and Italian style were beginning to hybridize. The E-minor Sonata, Opus 3, no.5, is cast in three movements, beginning with a highly decorated Allegro ma poco, an appealing middle-ground between French and Italian styles, leaning toward the latter. The second movement, a relaxed “gracious gavotte,” lands more decisively in French territory, and the finale more on the Italianate side.

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1786

Franz Anton Hoffmeister had high hopes when he commissioned Mozart to write three piano quartets in 1785, but things didn’t go as planned. According to Mozart’s biographer Georg Nicolaus von Nissen, “Mozart’s first piano quartet, in G minor, was thought so little of at first that the publisher Hoffmeister gave the master the advance portion of the honorarium on the condition that he not compose the other two agreed-upon quartets and that Hoffmeister should be released from his contract.”

Yes, you read that right: Nissen said that Hoffmeister paid Mozart to not write any more piano quartets than the one he had already finished. Although this recollection may be accurate in spirit, it seems to be slightly off in factual accuracy. It seems that by the time this arrangement was proposed, Mozart—thank heavens!—must have already gone on to complete the second of the three projected works, his Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493. He entered it on June 3, 1786, in the catalogue he kept of his musical compositions, immediately following his opera Le nozze di Figaro. When the E-flat–major piano quartet was published the next year, by the rival firm of Artaria, that company seems to have printed the piano, viola, and cello parts from plates it had purchased from Hoffmeister. That’s a strong indictment, since it suggests that Hoffmeister decided to withdraw from the project even if it meant sacrificing a good deal of nuts-and-bolts work that had already been expended on an edition. Artaria also made no money from the venture, and the third piano quartet was never written. In June 1788, the Journal des Luxus und der Moden pointed to the problem: it was too difficult for amateurs. “Many another piece keeps some countenance, even when indifferently performed; but in truth one can hardly bear listening to this product of Mozart’s when it falls into mediocre amateurish hands and is negligently played.”

One senses a dreamy quality in the opening movement, nowhere more than in the surprising modulation that heralds the development section. The melody at that point is a motif that pervades this movement, a figure that begins with a falling sixth, first heard as the second theme of the exposition. In the course of the movement, it is transposed to many keys and is heard in various instrumental combinations; at the very end, it even overlaps with itself in a bit of contrapuntal imitation. Where the G-minor piano quartet is taut and tense, the one in E-flat major tends towards luxuriance, which reaches its peak in the Larghetto. This is one of Mozart’s most eloquent slow movements, so rich in reiterations that it truly seems a conversation among the four participants.

Mozart had second thoughts about how to conclude this piece. He sketched out some delightful material that he decided not to follow through with; like the finale he did end up composing, it begins with a half-measure’s upbeat. The finale as it stands is essentially a rondo, but Mozart grafts onto it aspects of a sonata structure as well. A second principal theme, replete with a touch of characterful syncopation, follows the initial rondo melody, and later a blustery minor-mode passage, sounding ever so much like a development section, provides an occasion for the pianist to sweep up and down the keyboard with impressively virtuosic figuration while pursuing harmonic modulations. Throughout this movement, we find Mozart practically on the verge of a piano concerto, with the piano “soloist” and the strings operating in the back-and-forth contrast found in a concerto more than in the integrated style more typical of chamber music.

Concert in D major, Opus 21

Ernest Chausson

Born: January 20, 1855, in Paris

Died: June 10, 1899, in Limay, France

Work Composed: 1889–91

Ernest Chausson wrote mostly music of morbid melancholy though he enjoyed the sort of charmed existence that most artists could only dream of. The third child of the aptly named Prosper Chausson, a public-works contractor whose formative business years opportunely coincided with Baron Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris, the composer-to-be was schooled by a private tutor and developed such remarkable skills in writing and drawing that he had a hard time deciding which to pursue—or, indeed, whether he should seek a proper education in music. Instead, he went to law school. In 1877 he was sworn in as a barrister in Paris, but he never practiced. His more significant achievement that year was the composition of his first song, “Les Lilas” (The Lilacs).

Only in 1879, when he was 24 years old, did Chausson commit to studying music seriously. He enrolled at the Paris Conservatory as a composition student of Jules Massenet, who judged him to be “an exceptional person and a true artist.” But after failing to succeed at the annual Prix de Rome competition, a stepping-stone for French composers, he withdrew from the school, instead attaching himself to the circle that surrounded César Franck. It was Franck who ultimately provided the instruction and encouragement that enabled him to make a mark in the musical world despite his late start.

Chausson’s life unrolled with few frustrations apart from a brief period of military conscription. Generous as well as wealthy, he quietly funneled much-needed funds to less fortunate composer colleagues. He and his wife lived in urban comfort at their Parisian home in the affluent Parc Monceau neighborhood, which became a magnet for salon-seeking artistic types. It was during a quick retreat to the country in June 1899 that the composer, then 44 years old, headed out to exercise on that newly popular contraption, the bicycle. No one witnessed him lose control and crash into a brick wall, but the skull fracture he sustained was so severe that he must have died instantly. Claude Debussy, Gabriel Fauré, Henri Duparc, Albéric Magnard, and Paul Dukas were among the composers who occupied the pews at his funeral, and their ranks were filled out by such eminent figures as the artists Auguste Rodin, Eugène Carrière, and Edgar Degas.

The unusual title of this piece, Concert, had been used for certain chamber works by such late-Baroque figures as François Couperin, and the combination of solo violin and piano with an ensemble (string quartet) summons up something of the disposition of a Baroque concerto grosso. Nonetheless, Chausson’s writing reveals a deep sensitivity to a later chamber-music ideal, and the thematic linkage of its four movements shows how he absorbed the principles of thematic transformation and cyclic structures advanced by his mentor Franck. The lyrical, Fauré-like Sicilienne and the despondent Grave are outstanding by all counts, but the outer movements are not less impressive, with the Finale deftly manipulating themes heard earlier to bring this masterwork to a finely knit conclusion.

The Concert was premiered March 4, 1892, at a gathering of “Les XX” in Brussels; the performers were Ysaÿe (its dedicatee), pianist Auguste Pierret, and the Crickboom Quartet. The 37-year-old Chausson was so accustomed to failure by this point in his career that he scarcely knew what to make of the triumph this work scored. “Never have I had such a success!” he wrote in his diary. “I can’t get over it. Everyone seems to love the Concert. . . . I feel light and joyful, something I haven’t been for a long time. . . . I believe I’ll work with greater confidence in the future.”

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

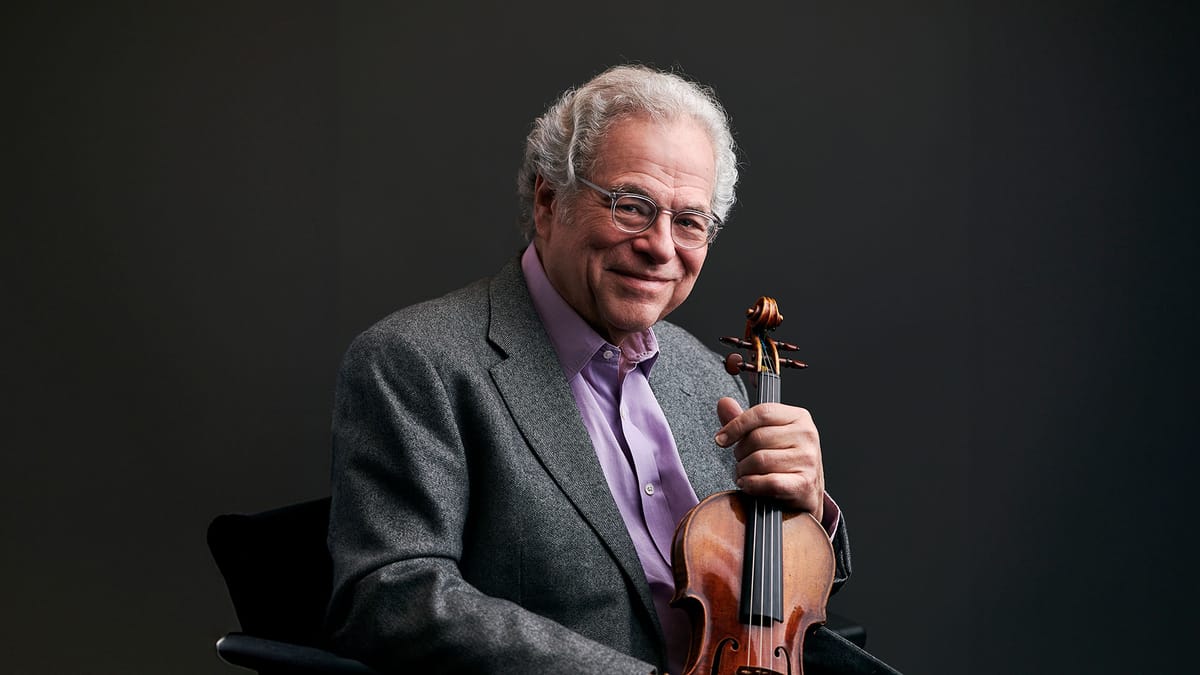

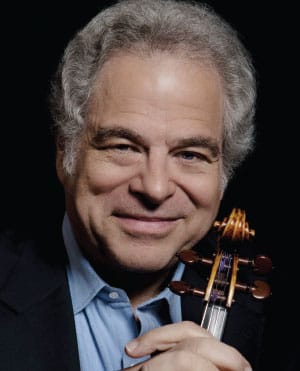

Itzhak Perlman

Having performed with every major orchestra and at concert halls around the globe, Itzhak Perlman was granted a Presidential Medal of Freedom–the nation’s highest civilian honor–by President Obama in 2015, a National Medal of Arts by President Clinton in 2000, and a Medal of Liberty by President Reagan in 1986. He has been honored with 16 Grammy Awards, four Emmy Awards, a Kennedy Center Honor, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and a Genesis Prize. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 1969.

This season, Perlman celebrates the 30th anniversary of his PBS special In the Fiddler’s House with performances across the country alongside today’s klezmer stars. He continues touring An Evening with Itzhak Perlman, and plays recitals across North America with pianist Rohan De Silva in their 25th anniversary season.

Over the past 30 years, Perlman has been devoted to music education, mentoring gifted young string players alongside his wife, Toby, in the Perlman Music Program. With close to 800 alumni, PMP is shaping the future landscape of classical music worldwide. Perlman also has an exclusive series of classes as the first classical music presenter with Masterclass.com.

Emanuel Ax

Born to Polish parents in what is today Lviv, Ukraine, Emanuel Ax moved to Winnipeg, Canada, with his family when he was a young boy. Ax made his New York debut in the Young Concert Artists Series, and in 1974 won the first Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Tel Aviv. In 1975 he won the Michaels Award of Young Concert Artists, followed four years later by the Avery Fisher Prize. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 1979.

His 2024–25 season began with a continuation of the Beethoven for Three touring and recording project with Leonidas Kavakos and Yo-Yo Ma. He recently appeared during the New York Philharmonic’s opening week, and returns to the Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, National Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Nashville Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, and Rochester Philharmonic.

Ax has been an exclusive Sony Classical recording artist since 1987. He has received Grammy Awards for the second and third volumes of his cycle of Haydn’s piano sonatas and made a series of Grammy-winning recordings with Ma of the Beethoven and Brahms cello sonatas.

Ax is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary doctorates from Skidmore College, New England Conservatory, Yale University, and Columbia University.

Jean-Yves Thibaudet

Jean-Yves Thibaudet is known for his diverse interests beyond the classical world—in addition to forays into jazz and opera, he has collaborated with film, fashion, and visual art. Recent appearances include the Boston Symphony on a European tour, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Houston Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Montreal Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, and Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France.

Thibaudet records exclusively for Decca and his extensive catalogue has received two Grammy nominations, two Echo Awards, Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik, Diapason d’Or, Choc du Monde de la Musique, Edison Prize, and Gramophone awards.

Born in Lyon, France, Thibaudet began his piano studies at age five, and entered the Paris Conservatory at 12. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994. Among his awards are the Victoire d’Honneur, induction into the Hollywood Bowl Hall of Fame, and being named an Officier by the French Ministry of Culture in 2012.

Juilliard String Quartet

Founded in 1946, the Juilliard String Quartet draws on a deep and vital engagement to the classics while embracing the mission of championing new works, a vibrant combination of the familiar and the daring. This season, the quartet tours to Amherst College, Chamber Music Monterey Bay, Musco Center, Concord Chamber Music Society, ATX Chamber Music and Jazz in Austin, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and People’s Symphony Concerts at New York’s Town Hall. European highlights include Wigmore Hall and Berlin Konzerthaus.

Sony Masterworks released The Early Juilliard Recordings in June 2021, and the quartet’s recordings of the Bartók and Schoenberg quartets, as well as those of Debussy, Ravel, and Beethoven, have won Grammy Awards. In 2011 the JSQ became the first classical music ensemble to receive a lifetime achievement award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

The JSQ is in residence at the Juilliard School and its members—Areta Zhulla, Ronald Copes, Molly Carr, and Astrid Schween—are all members of the string and chamber music faculties. The JSQ made its debut at the San Francisco Symphony in 1983.

Emanuel Ax’s recordings can be found on the Sony Classical and RCA labels.

Jean-Yves Thibaudet’s recordings can be found on the Decca, Warner/EMI Classics, Columbia, Universal Music, REM, and Naxos labels.

The Juilliard String Quartet’s recordings can be found on the Sony Classical label.

Management for Itzhak Perlman: Primo Artists (New York)

Management for Emanuel Ax: Opus 3 Artists (New York)

Management for Jean-Yves Thibaudet: HarrisonParrott (London)

Management for the Juilliard String Quartet: Colbert Artists Management (Pittsfield, Massachusetts)