In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, February 6, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, February 7, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, February 9, 2025, at 2:00pm

Paavo Järvi conducting

Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Opus 102 (1957)

Allegro

Andante

Allegro

Kirill Gerstein

Intermission

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 7 in E minor (1905)

Slow–Allegro risoluto ma non troppo

Nachtmusik I: Allegro moderato–Molto moderato (Andante)

Scherzo: Schattenhaft (Like a shadow)

Nachtmusik II: Andante amoroso

Rondo–Finale: Allegro ordinario–Allegro moderato ma energico

Paavo Järvi’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

Open rehearsals are endowed by a bequest from the Estate of Katharine Hanrahan.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half is Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 7, the most rarely performed of his 10 symphonies. “Three night pieces; the finale, bright day,” is how Mahler described the piece. It begins with a slow and shadowy first movement, whose dotted rhythms bobbed up from the composer’s subconscious while he was being rowed across an Austrian lake. The experience supplied him with a hook for a new symphony, ending a long bout of writer’s block.

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Opus 102

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg

Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1957

SF Symphony Performances: First and only—July 1993.

Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Dmitri Alexeev as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, timpani, snare drum, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

Soon after Dmitri Shostakovich had been denounced by the Soviet state for his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and temporarily “rehabilitated” through the contrite offering of his Fifth Symphony, he became the father of a son, Maxim, in 1938. Maxim eventually studied piano and conducting at the Moscow Conservatory, and he would enjoy an international conducting career, proving an enthusiastic champion of his father’s music, even leading the world premiere of Shostakovich’s final symphony in 1972. Shostakovich composed his Piano Concerto No. 2 for Maxim to use as he concluded his studies at the Moscow Central Music School, which provided preparatory studies for many young musicians aiming for the Moscow Conservatory. Although Maxim was by then a reasonably accomplished pianist, he had not yet appeared as a soloist with an orchestra. This was rectified on his 19th birthday—May 10, 1957, in the Large Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. He had hounded his father until he got the concerto he wanted. “I kept on and on asking him to compose something for me,” he later recalled. “He didn’t for quite a while. And then suddenly, he told me he’d written the Concerto.”

A new work by Shostakovich—who only the year before had been rapturously applauded by Soviet musical officialdom when he was awarded the Order of Lenin—ensured that Maxim’s debut as a concerto soloist would receive attention. According to Shostakovich biographer Laurel Fay, “critics were greatly taken with the concerto’s charming simplicity, carefree spirit, and lyrical warmth.” Maxim’s impressive debut earned him admission to the Moscow Conservatory. In a letter to his composer colleague Edison Denisov, written just a week after completing the concerto, Shostakovich dismissed his new piece as having no serious artistic merit. It is unclear what inspired him to speak so disparagingly of the work just then, but his comment is belied by the fact that he soon took the work into his own concerto repertoire and not infrequently appeared as the soloist himself.

The Music

The Piano Concerto No. 2 provides an abundance of delight, and its combination of sparkling vigor and technical forthrightness provides a perfect vehicle for younger pianists, as well as satisfaction for more mature ones. The opening Allegro unrolls almost as a series of piano etudes with a subservient accompaniment from the orchestra. The pianist faces a catalogue of technical devices, all of them elevated to a delectable musical context: exposed passages in octaves between the two hands, alertness to quirks of harmony and modernist melodic patterns, holding long notes and tracing melodies with separate fingers of a single hand, navigating scales with unpredictable twists and turns, negotiating wide-ranging arpeggios, close-contact hand-crossings. It is as if the composer were strolling through the halls of a conservatory, hearing a succession of etudes emanating from one practice room after another, and turning the whole thing into a travelogue bound together by his own distinct vocabulary.

Of course, Russian music students would also spend time playing compositions by Russian composers, and in the second movement, we catch a glimpse of earlier Russian Romanticism, sometimes redolent of Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff in its nostalgic mournfulness. The third movement (Allegro, but an Allegro a shade faster than the opening movement) grows out of this without a break. Again the scales and finger exercises seem familiar in their general contours—but woe to any soloist who goes on automatic pilot and is lulled into overlooking the deceptive variations in their intricate gyrations. Just when everything seems to be securely under hand, Shostakovich lurches from predictable 2/4 meter into out-of-kilter 7/8, and then complicates matters further by breaking that pattern with measures in still different meters.

In April 1981, while in West Germany directing a tour of the USSR State Radio and Television Orchestra, Maxim Shostakovich defected from the Soviet Union. He settled in the United States and was warmly welcomed when he conducted the National Symphony, on Memorial Day of 1981, on the West Lawn of the United States Capitol. His emigration led to the curious fact that when the State Music Publishing House in Moscow issued the score of the Piano Concerto No. 2 that year, as part of the complete works of Dmitri Shostakovich, the editors provided information about the date of the premiere but did not mention who the performers were on that occasion. As a defector, Maxim Shostakovich had achieved the rank of non-person in the Soviet Union, and as such, his performance had officially disappeared from Soviet history.

—James M. Keller

Symphony No. 7 in E minor

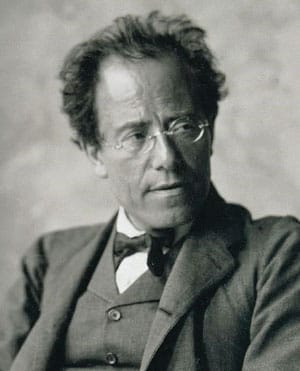

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1904–05

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1976. Seiji Ozawa conducted. Most recent—May 2019. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 4 flutes (4th doubling 2nd piccolo), piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tenor horn, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tambourine, cowbells, tam-tam, bass drum, small bells, orchestra bells, and glockenspiel), 2 harps, guitar, mandolin, and strings

Duration: About 75 minutes

Gustav Mahler began the Seventh Symphony in the middle. As a glance at the program page and Mahler’s own summary tell us, the structure is symmetrical. The first and last movements—both on a large scale—flank three character pieces, which are themselves symmetrical in that the first and third are each called Nachtmusik.

It was with these two night musics that Mahler began this score in the summer of 1904. But with summer’s end, a typically busy year began for Mahler, whose work as Europe’s most famous conductor occupied him throughout the concert season. In June 1905, Mahler headed back to his summer residence at Maiernigg, on the Wörther See, to continue work on his Seventh Symphony. He could not find the way into the composition. He took off for the Dolomites, hoping to release his creative energies, but nothing happened. Profoundly depressed, he returned. He stepped from the train and was rowed across the lake. With the first dipping of the oars into the water, he recalled later, “the theme of the introduction (or rather, its rhythm, its atmosphere) came to me.”

From that moment forward he worked like a man possessed, as indeed he must have been to bring this gigantic structure under control, even if not finished in detail, by mid-August. Thinking about the first performance, Mahler considered the New York Symphony, which he would be conducting in the 1907–08 season, but soon realized that this would be madness in a city and a country that knew so little of his music. A festival in Prague to celebrate the 60th year on the throne of Emperor Franz Joseph provided a more suitable occasion. Prague offered a less than first-rate orchestra; on the other hand, Mahler had ample rehearsal time, and the worshipful young conductors—among them Artur Bodanzky, Otto Klemperer, and Bruno Walter—who attended the preparations recounted how, refusing all help, he used every night to make revisions on the basis of that day’s experience. He was always the most pragmatic of composer-conductors.

The Nachtmusiken and the Scherzo made their effect at once; the first and last movements were harder nuts to crack. In Prague the reception was more respectful than enthusiastic. Mahler himself conducted the Seventh only once more, in Munich, a few weeks after the concert at Prague. It is still the least known of his symphonies.

The Music

The Seventh is a victory symphony, not a personal narrative but a journey from night to day. The focus is on nature. The opening is music in which we may hear not only the stroke of oars, but the suggestion of cortège. Here Mahler carries us from a slow introduction into the main body of a sonata-allegro movement. Settling into a new key, he brings in a gorgeous theme, a highly inflected violin melody full of yearning and verve, rising to a tremendous climax, to merge into the music of the second of the three marches we have heard. More such merges lie ahead. At the focal point of the development comes what must be the most enchanted minute in all Mahler, a transformation of the second march from focused to veiled, and an ecstatic vision of the glorious lyric theme. A sudden plunge of violins returns us, shockingly, to the slow introduction. The recapitulation has begun. It is tautly compressed. The coda is fierce and abrupt.

The opening of the first of the Nachtmusiken is a minute of preparation and search. A tremendous skid downwards through five-and-a-half octaves calls the proceedings to order. This artfully stylized version of an orchestra warming up turns into a tidy presentation of the theme that has been adumbrated. The theme itself is part march, part song, given a piquant flavor by that mix of major and minor we find so often in Mahler’s music. In later years, the Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg said that in this movement Mahler had been inspired by Rembrandt’s so-called Night Watch, but the composer Alphons Diepenbrock, also one of Mahler’s Amsterdam friends, both clarified and subtilized the issue: “It is not true that [Mahler] wanted actually to depict The Night Watch. He cited the painting only as a point of comparison. [This movement] is a walk at night, and he said himself that he thought of it as a patrol. Beyond that he said something different every time. What is certain is that it is a march, full of fantastic chiaroscuro—hence the Rembrandt parallel.”

The initial march theme is succeeded by a broadly swinging cello tune. Like many such themes by Mahler, this one, heard casually, seems utterly naïve; closely attended to, it proves to be full of asymmetries and surprises of every kind. Watch for the return of this tune, even more lusciously scored and with a new counter-theme in the woodwind. Distant cowbells become part of the texture, suggesting the Sixth Symphony, in which they play such a prominent part. Suddenly that great tragedy-in-music intrudes even more as a fortissimo trumpet chord of C major droops into minor. The string figurations collapse, there is a stroke of cymbals and tam-tam, and then nothing is left but a cello harmonic and a ping on the harp.

Mahler’s direction for the next movement, the Scherzo, is schattenhaft, literally “like a shadow” but perhaps better rendered as “spectral.” Drums and low strings disagree about what the opening note should be. Notes scurry about, cobwebs brush the face, witches step out in a ghostly parody of a waltz. The Trio is consoling—almost. The Scherzo returns, finally to unravel and disintegrate.

The first Nachtmusik was a nocturnal patrol, the second is a serenade that Mahler marks Andante amoroso. William Ritter, nearly alone in his time in his understanding of Mahler, gives a wonderful description of the way the second Nachtmusik begins: “Heavy with passion, the violin solo falls, like a turtledove aswoon with tenderness, down onto the chords of the harp. For a moment one hears only heartbeats. It is a serenade, voluptuously soft, moist with languor and reverie, pearly with the dew of silvery tears falling drop by drop from guitar and mandolin.” Those instruments, together with the harp, create a magical atmosphere.

After these four so differentiated night scenes comes the brightness of day, with a thunderous tattoo of drums to waken us. Horns and bassoon are the first instruments to be roused, and they lead the orchestra in a spirited fanfare whose trills put it on the edge of parody. Mahler’s humor gave trouble to many of his first listeners. Sometimes he maneuvers so near the edge of parody or of irony that, unless you know his language and his temperament, it is possible to misunderstand him completely, for example to mistake humor for ineptness. Few listeners here will fail to be reminded of Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger.

But what is that about? Again, Ritter understood right away, pointing out that Mahler never quotes Wagner but “re-begins” the Overture to take it far beyond. The triumphant C-major finale is itself a kind of cliché stemming from the Beethoven Fifth and transmitted by way of the Brahms First and, much more significantly for this context, Die Meistersinger. Mahler uses Die Meistersinger as a symbol for a good-humored victory finale. Other Meistersinger references occur, for instance the chorale to which the prize song is baptized, and even the deceptive cadence to which Wagner frequently resorts to keep the music flowing.

This Finale is a wild and wonderful movement. The Meistersinger idea turns out to be a whole boxful of ideas that, to an adroitly and wittily inventive builder like Mahler, suggest endless possibilities for combining and recombining, shuffling and reshuffling. To the city square music of Mahlerized Meistersinger he adds stomping country music. No part of the harmonic map is untouched, while the rhythms sway in untamed abandon.

Then we hear music we have not heard for a long time—the fiery march from the first movement. Or rather, we hear a series of attempts to inject it into the proceedings. Just as we think the attempt has been abandoned, the drums stir everything up again, and finally the theme enters in glory.

—Michael Steinberg

About the Artists

Paavo Järvi

Grammy Award-winning conductor Paavo Järvi serves as music director of the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, as the long-standing artistic director of the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, and as both the founder and artistic director of the Estonian Festival Orchestra.

As a guest conductor, Järvi regularly appears with the Berlin Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonia, and New York Philharmonic. This season, he conducts the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Berlin Staatskapelle, NDR Elbphilharmonie, Shanghai Symphony, and Hong Kong Philharmonic. He also continues to enjoy close relationships with many of the orchestras of which he was previously music director, including Orchestre de Paris, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, and Tokyo’s NHK Symphony Orchestra. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in April 2000.

In 2024, Järvi and the Tonhalle Orchestra received an International Classical Music Award for their recording of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 on Alpha Classics. Last September, the label released Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9, coinciding with the 200th anniversary of the composer’s birth. This spring, they release Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, the first release in a complete cycle which will span the seasons to follow.

With the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Järvi has won both the 2024 Opus Klassik and 2023 Gramophone Orchestra of the Year awards, as well as the 2019 Rheingau Music Prize and Opus Klassik Conductor of the Year. Other honors include a Grammy Award for his recording of Sibelius’s cantatas with the Estonian National Symphony, Gramophone and Diapason Artist of the Year, and Commandeur de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres awarded by the French Ministry of Culture. In 2015 Järvi was presented with the Sibelius Medal and in 2012 received the Hindemith Prize for Art and Humanity. As a dedicated supporter of Estonian culture, Järvi was awarded the Order of the White Star by the President of Estonia in 2013.

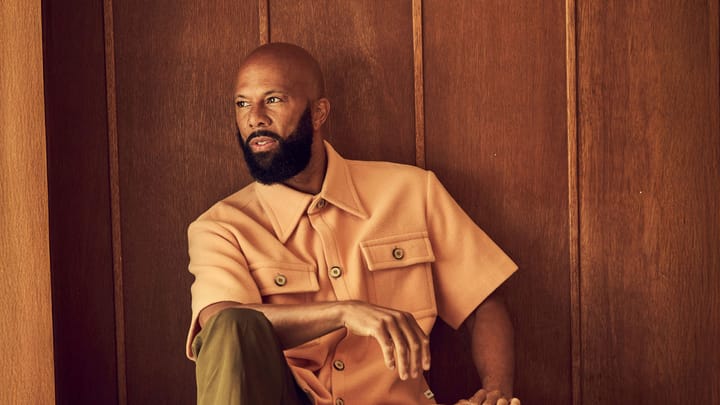

Kirill Gerstein

As a pianist, curator, educator, musical leader, and artistic collaborator, Kirill Gerstein explores resonant themes across a vast spectrum of repertoire—from Baroque suites and Classical concertos to contemporary creations, jazz, and cabaret.

Recently, Gerstein was artist in residence with the Bavarian Radio Symphony, a spotlight artist with the London Symphony Orchestra, a resident artist at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, and a curator at Wigmore Hall. Highlights of the current season include appearances with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Berlin Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, BBC Symphony, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, Dresden Staatskapelle, St. Louis Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, and Atlanta Symphony. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in July 2005.

Media projects, broadcasts, and digital innovation represent an integral part of Gerstein’s creativity. He has recorded for Platoon/Apple Music, Myrios, Deutsche Grammophon, Decca, and Berlin Philharmonic Recordings. Gerstein’s world premiere recording of Thomas Adès’s Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony was nominated for three Grammys and received the 2020 Gramophone Award. Since giving the world premiere, he has performed the work more than 50 times, with 20 different orchestras. Gerstein has also commissioned and premiered new works by Timo Andres, Chick Corea, Alexander Goehr, Oliver Knussen, and Brad Mehldau, among others.

At the age of 16, Gerstein completed his undergraduate and graduate degrees at the Manhattan School of Music. In 2001, he won the 10th Arthur Rubinstein Competition, and has also received the Gilmore Artist Award and an Avery Fisher Career Grant. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Manhattan School of Music in 2021 and serves on the faculty of Berlin’s Hanns Eisler Hochschule and the Kronberg Academy.