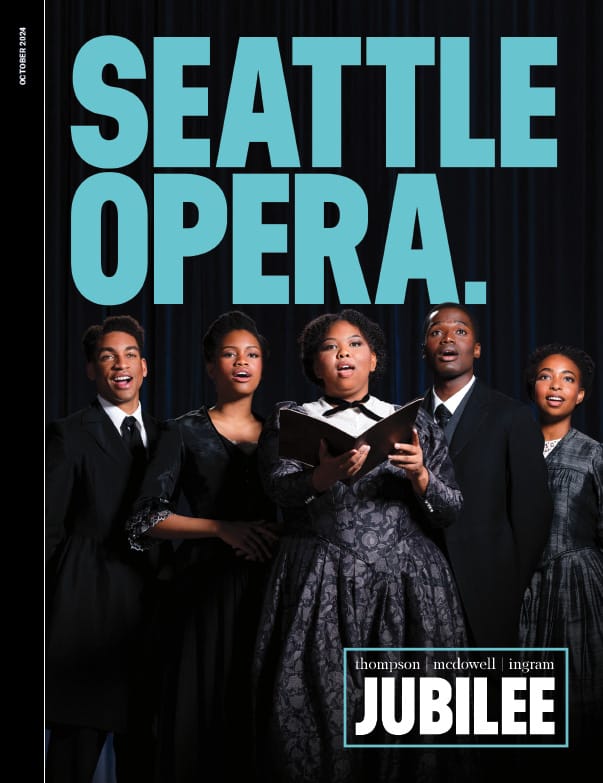

October 12–26, 2024 | World Premiere

In This Program

- Show Information

- Who’s Who

- Letters

- Features

- Additional Information

Jubilee

Production Sponsors

Principal Singer Season Sponsor

Joan Watjen

in Memory of Craig M. Watjen

Production Sponsors

Microsoft

Artist Sponsor

Brian LaMacchia

Shawn Duan, Projection Designer

We are deeply grateful to you, Seattle Opera’s 3,600+ Annual Fund Donors. Your passion for opera and contributions at every dollar amount inspire great performances in McCaw Hall and support engaging activities at the Opera Center and throughout Washington State all season long!

Thank you!

Created and Directed by Tazewell Thompson

Vocal Arrangements, Additional Music, Lyrics by Dianne Adams McDowell †

Orchestrations by Michael Ellis Ingram †

World Premiere

Performances at McCaw Hall: October 12, 13, 16, 19, 20, 22, 25, & 26, 2024

Evening Performances: 7:30 PM

Matinees: 2:00 PM

School Matinee: 10:30 AM

Act I: 64 minutes

Intermission: 25 minutes

Act II: 68 minutes

In English with English captions

CONDUCTOR

Kellen Gray †

CREATOR & DIRECTOR

Tazewell Thompson

VOCAL ARRANGER

Dianne Adams McDowell †

ORCHESTRATOR

Michael Ellis Ingram †

SET DESIGNER

Donald Eastman

COSTUME DESIGNER

Harry Nadal †

LIGHTING DESIGNER

Robert Wierzel

SOUND DESIGNER

Robertson Witmer

PROJECTION DESIGNER

Shawn Duan †

WIGS, HAIR, & MAKEUP DESIGNER

Ashlee Naegle

FIGHT DIRECTOR

Geoffrey Alm

ENGLISH CAPTIONS

Jonathan Dean

Cast

AMERICA ROBINSON

Tiffany Townsend †

MAGGIE PORTER

Aundi Marie Moore †

MINNIE TATE

Sarah Joyce Cooper †

MABEL LEWIS

Ibidunni Ojikutu

JENNIE JACKSON

Hannah Jones †

GEORGIA GORDON

Natalie Lewis †

ELLA SHEPPARD

Lisa Arrindell †

ISAAC DICKERSON

Tyrone W. Chambers II †

FREDERICK LOUDIN

Martin Luther Clark †

GREENE EVANS

Martin Bakari

EDMUND WATKINS

Darren Drone

BENJAMIN HOLMES

Greg Watkins †

THOMAS RUTLING

Aubrey Allicock

ASSISTANT CONDUCTOR

Philip A. Kelsey

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

Mike Janney

ENSEMBLE COACH

Michaella Calzaretta

MUSIC PREPARATION

Philip A. Kelsey

David McDade

Jay Rozendaal

STAGE MANAGER

Keri Muir

ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGERS

Quinn Chase

Bethany Windham

Jubilee was originally commissioned by South Coast Repertory

Jubilee Premiered at the Arena Stage, Washington, DC, May 2019

Molly Smith, Artistic Director, and Edgar Dobie, Executive Director

Produced by arrangement with The Barbara Hogenson Agency, Inc. All rights reserved.

† Seattle Opera mainstage debut

Opera presentation and production © Seattle Opera 2024. Copying of any performance by camera, audio, or video recording equipment, and by any other copying device, and any other use of such copying devices during the performance is prohibited.

The Story

Act I

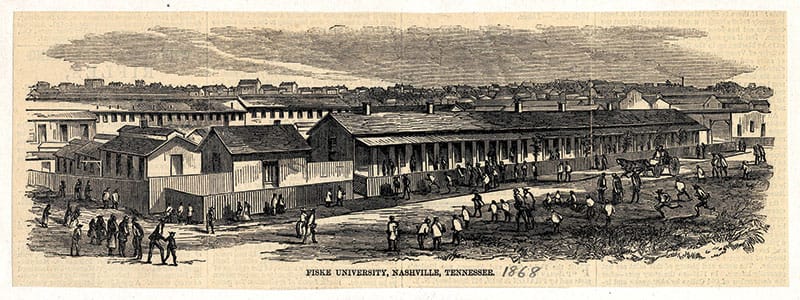

Nineteenth century. A theater in Nashville, Tennessee.

Thirteen members of the Fisk Jubilee Singers are gathering behind the curtain in vocal warmups, preparing to perform their concert of spirituals. Post show, the singers retreat to the old military barracks set aside by northern abolitionists to house those who were formerly enslaved, now students and teachers of Fisk University.

While turning over the earth in their pitiful vegetable garden, their excavation makes a gruesome discovery. Buried beneath the surface of the ground, instruments of slavery and bondage: chains, manacles, shackles, harnesses, iron masks, and mouth muzzles. The singers sell them for Bibles and spellers. To raise funds for their school, the singers sing at a ladies’ tea, in a fashionable part of Nashville.

They sing for funds in small towns and on street corners, through all kinds of weather. Stranded at a railway depot, a jeering white mob attacks the singers and beat them, mercilessly. Undaunted, the singers pack their meager belongings and continue their fundraising tours. In a church basement practice hall rehearsal, the singers receive news of an invitation from Queen Victoria to sing at a command performance in England. The singers rehearse their program for the Queen.

Intermission

Act II

The Fisk Jubilee Singers arrive in London and, at Buckingham Palace, perform for Queen Victoria. They return home to Tennessee by ship, train, and horse-drawn carriage. Projecting into the future, the men sing at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, NYC. The women sing at a special church service. The singers gather and listen, as a first recording of the Fisk Jubilee Singers is released. In the epilogue we hear their individual postmortems.

From the President of Fisk University

On Friday, October 6, 1871, the day that nine Fisk University students embarked on a journey “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” they could not have imagined that the spirituals they had learned from the enslaved, during secret religious services, and inside slave cabins would be the cornerstone of a musical style that is performed throughout the world as well as the foundation for a striving university community. Carrying their few belongings, the group that would become the Fisk Jubilee Singers walked from the grounds of an abandoned army hospital to the train station armed with faith and hope.

I’m not surprised that Tazewell Thompson and Seattle Opera are sharing the story of these early Jubilees; the ensemble’s triumphs and hardships are tremendous, a narrative fitting of grand opera. Maggie Porter, Thomas Rutling, Ella Sheppard, Minnie Tate, Isaac Dickerson, and the other students who took part in the first three tours were champions who fought bitter conditions each day they were away from their community in Nashville, Tennessee. A courageous troupe—some formerly enslaved, a few barely teenagers, several skilled speakers, and one a talented pianist—they believed that songs like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Balm in Gilead,” “Go Down, Moses,” and others could help build the foundation of a new school. Today, Fisk University still enjoys usage of the magnificent Jubilee Hall, built in 1876, and was the first permanent structure erected on campus. Their musicianship and dignity impressed religious leaders, activists, heads of states, royalty, and everyday people across the United States, Great Britain, and Europe.

Thanks, in part, to the singers’ courage and ingenuity, Fisk University is Nashville’s first institution of higher education as well as a top-ten historically Black university, according to US News and World Report. Our more than twenty areas of study are grounded in the liberal arts with emphasis in the natural and social sciences, business, and the humanities. A Fisk education prepares students to be beacons in servicing the community and well-rounded leaders and scholars in their respective fields. Our graduates are doctors and lawyers, entrepreneurs and innovators, educators and scholars, artists and musicians, and more.

The entire Fisk University community, which includes more than 1,000 current students, the alumni, board of trustees, faculty, and staff, is grateful to Seattle Opera and Tazewell, especially, for finding inspiration in the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Sincerely,

Dr. Agenia Walker Clark

Bringing Jubilee to Opera

By Tazewell Thompson

“over my head, i hear music in the air;

over my head, i hear music in the air;

there must be a god somewhere.”

That spiritual begins my opera, Jubilee.

My earliest memories are of being constantly engulfed with music, sounds, lyrics, words. Rarely did a moment of silence interrupt this overwhelmingly awesome orchestral assault!

“dere’s no hidin’ place down here;

i went to the rock to hide my face;

the rock cried out—‘no hidin’ place’;

dere’s no hidin’ place down here!”

I was taken from my mother and father at a very early age. Made a ward of the state. They were deemed irresponsible, unsafe, unsuitable, unfit to raise children. Under a not so fatalistic star, they might’ve led, separately, respectable lives and contributed, in some way, to my upbringing and to society. On their wedding day, unborn me in my mother’s belly, they fought while walking down the aisle in the storefront church after exchanging vows.

“sometimes i feel

like a motherless child;

a long way from home...”

My drifter-dreamer father was a struggling pick-up band alto saxophonist. My startlingly beautiful mother, with a voice to match, and visions of stardom, devoured Jet, Ebony, movie magazines. Both allergic to earning an honest paycheck. They unlawfully lifted anything not tied down. From their aggressive klepting, they possessed an enormous collection of records they treasured. My father’s favorites: Coltrane, Ellington, Basie, Monk, Armstrong. My mother’s: Ella, Billie, Dinah, Sarah, Lena.

“ezekiel saw the wheel, way in the middle of the air.”

I have fond memories of their singing (my mother) and playing (my father) along with these beautiful classic jazz and blues recordings. Sounds and lyrics were interrupted by their frequent bouts of verbal fisticuffs. As a pair they were incorrigible. I so loved them both.

“it’s me, it’s me, it’s me, oh, lord,

standin’ in the need of prayer.”

As parents: A disaster. Five and four years after bringing, respectively, myself and my younger sibling into the world, I was saved, from a fire, but through their tragic team negligence, the fire took my brother’s life.

“nobody knows the trouble i’ve see, lord; nobody knows my sorrow.”

I was placed and spent seven years of my childhood living at St. Dominic’s Convent in Blauvelt, New York. I was in a home, protected and loved by a progressive Dominican order of nuns. I was the only Black boy in my class of thirty.

“there is a balm in gilead to make the wounded whole. there is a balm in

gilead to heal the sin-sick soul.”

I was an altar boy and a boy soprano learning the music of my new religion—Roman Catholic—baptized, first communion, and confirmation, all in the same year. I learned how to read music, read and write Latin. Was I learning and knowing the Gregorian chants, liturgical music, or hymns? Yes. Was it deep and in detail? No. It was opera.

“pace, pace mio dio! crudo sventura

m’astringe, ahimè, a languira ...”

Sister Benvenuta taught music on Tuesdays and Thursdays. A tall, elegant, thin figure behind her white Dominican Sisters habit; black hard-arched veil, black laced-up chunky practical heels, long, boney fingers with a pitch pipe eternally clutched to her like a third hand; a smooth, comforting whisper of a voice; herself, a sweet soprano.

“o mio babbino caro; mi piace, e bello

bello; vo ‘andare in porta rossa ...”

Sister Benvenuta would wheel a metal, cage-like trolley that contained on top a record player, and housed in the two compartments below, her prized possession of long-playing opera records, compliments of The Longines Symphonette Society. Sister acquainted us with the synopses of the great opera warhorses. She played particular selections and taught us what to listen for. She waxed ecstatic over the voices that filled the classroom: Callas, Caruso, Tebaldi, Sutherland, Corelli, Nilsson, Merrill, Lanza, Tucker, Sills. She would speak of style, size, and range; use expressions like, “silvery, silky, shimmering, bell-like, brassy, breathy, coloratura, vibrato, trills, timbre, tremolo, agile, angelic, lilting, ringing, fireworks, bombastic” and one that scarified me: “Castrato!”

“gonna ride up in the chariot soon-a in the morning; and i hope i’ll join the band!”

One Tuesday morning, Sister Benvenuta called, “Mr. Thompson.” (For seven years I almost forgot I had a given first name, always addressed by my surname.) “Mr. Thompson, please see me in my office after class. I want you to hear something that personally connects and concerns you.”

“what lies over the ocean, lord?

what lies over the sea?

who is this hand that reaches out, lord?

is this hand for me?”

Sister Benvenuta played, for my benefit, records she acquired of great Black artists: Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Roland Hayes, Leontyne Price, Mahalia Jackson. “They are singing Negro Spirituals, introduced by a group called The Fisk Jubilee Singers. When you leave us and move on with your life, you must find out more about this astonishing group, that created music in your image. They inspired the work of some of my closest ‘friends’, Dvorak, Delius, Gershwin.”

“go down, moses; let my people go.”

I listened and loved it all: the abundant fund of compelling, addictive, syncopated melody; personally lived storytelling. Songs that are spare, precise, emotionally soaring, gut-wrenching, heartfelt, and heartbreaking; themes of pride, fear, faith, courage, loss, renewal, joy, celebration, and community. A full circle re-introduction to the music, blues and jazz—all with echoes of spirituals—like my parents shared with me. A fulsome introduction to the earliest music of my people.

“lord, i got a right, lord,

i got a right to sing in the tree of life!”

As I “moved on,” I rediscovered, deeper, the source of spirituals. I saw a documentary about the Fisk Jubilee Singers. I was intrigued by the story of these extraordinarily courageous and gifted, hitherto enslaved human beings, who set off from Nashville, Tennessee, on fundraising concerts, touring America and Europe performing spirituals to save their crumbling, beloved Fisk Free Colored School—eventually renamed Fisk University. The Jubilees sacrificed, going without food, freezing in the winter, often suffering from illnesses and violent hostility on a punishing tour schedule—because they knew that education was the path to real power and individual personhood.

“set down, servant! i can’t set down!

my soul’s so heavy that i can’t set down.”

I became obsessed, was determined, wanting to know more. I began to collect anything related to spirituals: old vinyl, CDs, books, and sheet music. I thought of an opera around the spirituals. When a commission to write a play was offered, I knew I wanted to tell the story of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. After a highly successful and extended run of Jubilee, my a capella musical at Arena Stage in Washington D.C., I spoke with Christina Scheppelmann of Seattle Opera about Jubilee. She instantly saw it as an opera. A major American opera house. A cause for celebration!

“great day! great day!

great day, the righteous marching!”

The journey of the Fisk Jubilee Singers is very much the story of the Negro Spiritual. Why do these songs matter, why do they endure? The earliest songs sung in America are those songs sung by the enslaved—as early as the beginning of the 17th century—known as field songs, folk hymns, cabin songs, secret songs, sorrow songs, plantation melodies, hand-me-down songs, shouts, spirituals, or jubilees.

“didn’t my lord deliver daniel; deliver daniel; then why not every man?”

The songs matter because the men and women who sang and “composed” them expressed their faith, pain, anguish, hope, loss, love, and resilience in these songs as they struggled from day to day—even as they labored to help shape and build this country, they planted the roots, erected the scaffold, designed a blueprint, added a spine—it was the heart and soul of what became gospel, blues, jazz, R&B, country, folk, and hip-hop.

“there’s plenty good room; plenty good room; in my father’s kingdom.”

These glorious spirituals, songs of certain proportion and dimension, worthy of unearthing, not once, but time after time again, provide an intense work of the human spirit that has within it a deep accumulation of human substance, both of belief and empathy. It is from this richness that it derives both its power to entertain and captivate and, simultaneously, to change people’s recognition of themselves and their world. To see ourselves more in each other. To educate. That was what those young, intrepid students sought as they sang their songs to the world: Leaving a legacy to educate and save their institution of education.

“do lord, do lord; do remember me;

oh, when i am gone, lord;

do remember me.”

Reprinted with permission from Opera Magazine.

Notes From the Vocal Arranger

By Dianne Adams McDowell

The score of Jubilee is a reflection of a tiny seed that was planted in the mind of Tazewell Thompson. He promised that, someday—when the time was right—we would embark on it together. Many years later, when that seed finally sprouted, I instinctively knew that each and every spiritual setting had to be drawn directly from the dramatic moments which Tazewell so carefully curated. And, musically speaking, I wanted to respect the rich tradition of the spirituals while, at the same time, opening them up to new engaging rhythms and fresh harmonic colors—a little gospel, R&B, and a smattering of the blues!

By the time Tazewell had finished the first draft of the libretto, he had amassed a veritable library on the lives, struggles, and music of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. With all of this wonderful material at my fingertips, I immersed myself in it, learning about these talented, courageous, and dedicated young individuals, listening to their stories, hearing their voices and, through them, finding my own inspiration to bring the fully a cappella score to life. With the addition of glorious orchestrations by Michael Ellis Ingram, Tazewell and I watched the seed that was Jubilee blossom into a beautiful tree.

Notes From the Orchestrator

By Michael Ellis Ingram

I have spent the last two years inside of Tazewell Thompson’s mind. It started off with our 2022 production of Porgy & Bess at Des Moines Metro Opera, where we became fast friends who relished each other’s approach to theater. When I was asked to lead Blue at New Orleans Opera in 2023, I jumped at the opportunity to visit Tazewell in Harlem beforehand to discuss his libretto. Jubilee is now our third collaboration, and to vamp on our beloved Sondheim, we got a good thing going. Black people have been making every kind of music for as long as music has existed.

That’s why I folded every style imaginable into the orchestration that accompanies Dianne Adams McDowell’s stunning vocal arrangements for Jubilee. Sweeping symphonic gestures dissolve into fragile madrigals. A raucous second line prances past an aria. A hushed chorale shimmers like an impressionist tone poem while a sultry monologue shimmies into a night club jazz ballad. I even included what may be the first ever symphonic praise break. (Please bring your fans and your tambourines.)

The music that was most moving for me to write was the underscore to the mob scene. I tried to channel the fear and rage of all who came before me and suffered in my place by skewing the various spiritual melodies beyond all recognition. Grimacing atonal fragments are punctuated by the most violent sounds I could conjure from the orchestra. As the violence subsides and a single voice rises from the ashes, the accompaniment continues to quiver in the shadows, even as the radiant hope that defines the opera dawns on the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Who’s Who

Artists

TAZEWELL THOMPSON

Creator and Director (Harlem, NY)

Seattle Opera Debut: Stage Director, Blue (’22)

Tazewell Thompson is the 2020 Music Critics Association of North America award recipient with Jeanine Tesori for Best New Opera in North America for Blue; The New York Times, Washington Post: Best in Classical Music 2019, and The Guardian 2023. He has over 150 directing credits in opera houses and theaters in the US, France, Spain, Italy, Africa, Japan, Netherlands, and Canada. EMMY Nominations for Best Director and Best Classical Production for Porgy and Bess Live from Lincoln Center. Blue productions include: Glimmerglass Festival, Washington National Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Toledo Opera, Michigan Opera, New Orleans Opera, English National Opera, and Dutch National Opera.

DIANNE ADAMS MCDOWELL

Vocal Arranger (Fairmont, VA)

Seattle Opera Debut

Dianne Adams McDowell is the vocal arranger of A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder, with seven Drama Desk Awards; four Tony Awards (including Best Musical), and 2015 Grammy nomination. Her commissions include Radio City Music Hall’s Magnificent Christmas Spectacular, The Wind in the Willows at New Victory Theatre, and the Gospel Mass at St. Paul & the Redeemer in Chicago. She received the Philadelphia Barrymore Award, the Beverly Hills/Hollywood NAACP Award, and a Helen Hayes Award nomination for Tazewell Thompson’s Constant Star. Her vocal arrangements have been performed at Lincoln Center, Hartford Stage, Actors’ Theatre of Louisville, Syracuse Stage, Avery Fisher Hall, The Old Globe Theatre and abroad in Tokyo, Shanghai, Seoul, Melbourne, and Stockholm.

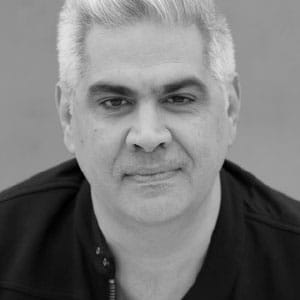

MICHAEL ELLIS INGRAM

Orchestrator (Dresden, Germany)

Seattle Opera Debut

Composer and orchestrator Michael Ellis Ingram celebrates simultaneous world premieres on two continents with Seattle Opera’s production of Jubilee and Theater Bremen’s production of his musical

The 35th of May. He also wrote book, music, and lyrics and debuted as stage director of the musical Erwin and Elmire, which opened in June 2024 at the Mecklenburgisches Staatstheater Schwerin. He currently serves as Chief Conductor of the Staatsoperette Dresden. Ingram conducts opera in Boston, New York, New Orleans, Chicago, Portland, and Des Moines, and he has taught conducting in Dresden, Leipzig, Hamburg, and Salzburg.

AUBREY ALLICOCK

Thomas Rutling

Bass-Baritone (Tucson, AZ)

Seattle Opera Debut: Cesare Angelotti, Tosca (’15)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Figaro, The Marriage of Figaro (’16); Minskman, Flight (’21)

Engagements: Tiridate, Radamisto (Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra); Dick Hallorann, The Shining (Lyric Opera Kansas City and Atlanta Opera); Alberich, Das Rheingold (Dayton Opera); Leporello, Don Giovanni (Sacramento Opera and Philharmonic); Don Alfonso, Così fan tutte (Opera Saratoga)

Geoffrey Alm

Fight Director (Seattle, WA)

Seattle Opera Debut: War and Peace (’90)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Pagliacci (’24), A Thousand Splendid Suns (’23); Il trovatore (’19); The Ring (’13, ’00)

Engagements: Fat Ham (Seattle Rep); Sweat (ACT Theatre); Macbeth (Seattle Shakespeare Company)

LISA ARRINDELL

Ella Sheppard

Soprano (Brooklyn, NY)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Ella Sheppard, Jubilee (Arena Stage); Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (Broadway); Tyler Perry’s Madea’s Family Reunion (Lionsgate); Law & Order (NBC); Watson (CBS); Carol, Albany Road (Faith Filmworks)

MARTIN BAKARI

Greene Evans

Tenor (Yellow Springs, OH)

Seattle Opera Debut: Peter the Honeyman, Porgy and Bess (’18)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Mime, Das Rheingold (’23); Jalil/Wakil/Guard, A Thousand Splendid Suns (’23); Don Basilio, The Marriage of Figaro (’22)

Engagements: Charlie Parker, Charlie Parker’s Yardbird (Atlanta Opera, Arizona Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Dayton Opera, New Orleans Opera, and Indianapolis Opera); Tenor Soloist, Messiah (Oratorio Society of NY at Carnegie Hall); Tenor Soloist, Carmina Burana (Cecilia Chorus of NY at Carnegie Hall); Dr. Caius, Falstaff (Houston Grand Opera); Frederic, The Pirates of Penzance (Virginia Opera and Kentucky Opera); Tenor, United Kingdom Recital Tour (Mirror Visions Ensemble)

TYRONE W. CHAMBERS II

Isaac Dickerson

Tenor (New Orleans, LA)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Police #1/Buddy #1, Blue, Don Basilio, The Marriage of Figaro (New Orleans Opera); Pasterz, Król Roger, Dele Piebald, Quamino’s Map, Russell Davenport, Freedom Ride (Chicago Opera Theater); Buddy Sorrell, Life and Love of Joe Coogan (Lehigh University)

MARTIN LUTHER CLARK

Frederick Loudin

Tenor (Marshall, TX)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Walther, Tannhäuser (Houston Grand Opera); Candide, Candide (Madison Opera); Luis Rodrigo Griffith, Champion and CJ, The Factotum (Lyric Opera of Chicago); Jonathan Dale, Silent Night, and Brother, Seven Deadly Sins (Wolf Trap Opera); Master Slender, Sir John in Love (Bard Music Festival)

SARAH JOYCE COOPER

Minnie Tate

Soprano (Lincoln, MA)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Soloist, John Rutter’s Magnificat (Carnegie Hall); Soloist, Mass in Blue (Harvard Radcliffe Chorus); Recital and Concert Soloist, Mozart, Songs, and Spirituals (Bar Harbor Music Festival); Clorinda, La Cenerentola (Tri-Cities Opera and Syracuse Opera); Anne Hutchinson, American Jezebel (Harvard University); Tebaldo, Don Carlo (Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra)

DARREN DRONE

Edmund Watkins

Baritone (Sherwood, AR)

Seattle Opera Debut: Baron Douphol, La traviata (’23)

Engagements: Adult James/Foreman, Fire Shut Up in My Bones (Metropolitan Opera); Belcore, The Elixir of Love (Florentine Opera Company); Marcello, La bohème (Glimmerglass Festival); Falstaff, Falstaff (Portland Opera); Alfio, Cavalleria rusticana (Utah Opera); Germont, La traviata (Berkshire Opera Festival)

SHAWN DUAN

Projection Designer (New York, NY)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Mother Play (Broadway: Helen Hayes); Between Two Knees (Perelman Performing Arts Center, Seattle Repertory Theatre, and Oregon Shakespeare Festival); Letters of Suresh (Second Stage Theater); Paulownia (Crystal Bridges Museum); Bruce (Seattle Rep); Chinglish (Broadway: Longacre Theatre)

DONALD EASTMAN

Set Designer (Houston, TX)

Seattle Opera Debut: Falstaff (’10)

Young Artists Program Designer (’06–’12)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Blue (’22); Don Quichotte (’11)

Engagements: Set Designer, Blue (Washington National Opera and Chicago Lyric Opera); Evelyn Brown (Princeton University, La MaMa ETC); The Rake’s Progress (Opera Omaha)

KELLEN GRAY

Conductor (Rock Hill, SC)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Guest Conductor, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Houston Symphony Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, and Philharmonia Orchestra; Associate Artist, Royal Scottish National Orchestra

HANNAH JONES

Jennie Jackson

Mezzo-soprano (Houston, TX)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Soloist, 2024 Summer Recital Series (Metropolitan Opera); Madame de la Haltière, Cendrillon, Hermia, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Maman/La Libellule, L’enfant et les sortilèges (Manhattan School of Music); La Zia Principessa, Suor Angelica (Seagle Festival)

Hannah Jones appears by kind permission of the Metropolitan Opera Lindemann Young Artist Development Program.

NATALIE LEWIS

Georgia Gordon

Mezzo-soprano (Bedford, MA)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: La Frugola, Il tabarro, La Zelatrice, Suor Angelica, Zita, Gianni Schicchi (Deutsche Oper Berlin); Kate Pinkerton, Madame Butterfly, Governess, Pique Dame (Bayerische Staatsoper); Lucretia, The Rape of Lucretia (Merola Opera)

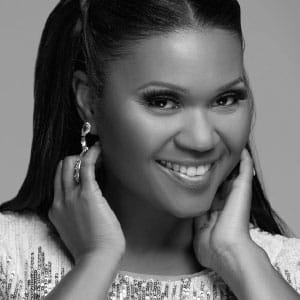

AUNDI MARIE MOORE

Maggie Porter

Soprano (Bowie, MD)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Strawberry Woman, Porgy and Bess (Metropolitan Opera); Mother Abbess, The Sound of Music (Virginia Arts Festival); Mother, Blue (Toledo Opera and Dutch National Opera); Soprano Soloist, Cantata for a more Hopeful Tomorrow (The Washington Chorus); Guest Soprano, Haydn + Price (Pacific Chorale)

HARRY NADAL

Costume Designer (San Juan, Puerto Rico)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Costume Designer, Dial M for Murder (Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center); Laughs in Spanish (Hartford Stage); Parrots at the Pagoda (Pregones/PRTT); It Happened in Key West (Fulton Theatre); And the World Goes Round (Florida Studio Theatre); Porgy & Bess (Des Moines Metro Opera)

ASHLEE NAEGLE

Wig, Hair, and Makeup Designer (Las Vegas, NV)

Seattle Opera Debut: Hair and Makeup Intern Julius Ceasar (’07)

Ashlee Naegle made a name for herself early on in her career by mastering the dying art of wig building. She created and designed for several companies around town until the Seattle Opera created an in-house Hair and Makeup Designer position for her in 2017. During her time as the in-house Hair and Makeup Designer, she has built a sizable wig collection, built a department, and set high standards for wigs, hair, and makeup. With each production, her designs are custom built for the performers and their characters to create a believable façade for the audience as well as to complement the costumes and production as a whole.

IBIDUNNI OJIKUTU

Mabel Lewis

Soprano (Bellingham, WA)

Seattle Opera Debut: Strawberry Woman, Porgy and Bess (’11)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Neighbor/Ensemble, X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X (’24); Soloist, The Human Family: A Recital (’24); Wife #2/Market Woman #2, A Thousand Splendid Suns (’23)

Engagements: Antron’s Mother, The Central Park Five (Portland Opera); Soprano Soloist, Holiday Concert (Bellingham Symphony Orchestra); Recitalist, Wisdom (The Lincoln Theater), Featured Artist, In the Garden of Sonder (Lakewold Gardens); Recitalist, The Earth is a Living Thing (Jansen Art Center)

TIFFANY TOWNSEND

America Robinson

Soprano (Jackson, MS)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Idleness, The Romance of the Rose (Long Beach Opera); Soprano Soloist, Verdi’s Requiem (Bakersfield Symphony and New Jersey Symphony); Soprano Soloist, George Walker’s Lilacs (New Jersey Symphony); Donna Elvira, Don Giovanni, First Playmate Der Zwerg (LA Opera)

GREG WATKINS

Benjamin Holmes

Baritone (Washington, DC)

Seattle Opera Debut

Engagements: Benjamin Holmes, Jubilee (Arena Stage and Alabama Shakespeare Festival); Professor Callahan, Legally Blonde (Keegan Theatre); Zoser, Aida (Constellation Theatre Company); Curtis Jackson, Sister Act (Arts Centric); Polyneices, Gospel at Colonus (Avant Bard); Governor Von Richterhenkenflichtgetruber, Desperate Measures (Constellation Theatre Company)

ROBERT WIERZEL

Lighting Designer (Branford, CT)

Seattle Opera Debut: Turn of the Screw (’94)

Previously at Seattle Opera: Blue (’22); Don Giovanni (’21); Eugene Onegin (’20)

Engagements: Still/Here (Brooklyn Academy of Music); Blue, The Marriage of Figaro (Lyric Opera of Chicago); Siegfried (The Atlanta Opera); The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs (Washington National Opera); Leopoldstadt (The Huntington & Shakespeare Theatre Company); Rigoletto (LA Opera)

ROBERTSON WITMER

Sound Designer (Seattle, WA)

Seattle Opera Debut: The Falling and the Rising (’19)

Previously at Seattle Opera: X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X (’24); Das Rheingold (’23); A Thousand Splendid Suns (’23)

Engagements: Sound Designer, Camelot (Village Theatre); Composer, Murder in the Alps (Laguna Playhouse)

Orchestra

Violin I

Noah Geller, Concertmaster

Emerson Millar, Assistant Concertmaster

Jacqueline Audas

Jennifer Bai

Leonid Keylin

Ji Yeon Lee

Andy Liang

Caitlin Kelley

Violin II

Cameron Daly, Principal

Gennady Filimonov, Asst. Principal

Natasha Bazhanov

Brittany Breeden

Xiao-po Fei

Seunghoon Lee

Victoria Parker

Viola

Katie Liu, Principal

Timothy Hale, Asst. Principal

Wesley Dyring

Ursula Steele

Daniel Stone

Jordan Voelker

Cello

Meeka Quan DiLorenzo, Principal

Eric Han, Asst. Principal

Sunnat Ibragimov

Emily Hu

Charles Jacot

Double Bass

Jordan Anderson, Principal

Travis Gore, Asst. Principal

Jennifer Godfrey

Todd Larsen

Flute

Demarre McGill, Principal

Robin Peery

Piccolo

Robin Peery

Oboe

Ben Hausmann, Principal

Stefan Farkas

English Horn

Stefan Farkas

Clarinet

Emil Khudyev, Principal

Eric Jacobs

Bass Clarinet

Eric Jacobs

Bassoon

Seth Krimsky, Principal

Kipras Mažeika

Contrabassoon

Kipras Mažeika

Horn

Mark Robbins, Principal

Jenna Breen

Trumpet

David Gordon, Principal

Mike Myers

Trombone

Ko-ichiro Yamamoto, Principal

Carson Keeble

Eden Garza

Timpani

Matt Decker, Principal

Percussion

Michael Werner, Principal

Rob Tucker

Personnel Manager

Constance Aguocha

Assistant Personnel Manager

Keith Higgins

Rotating members of the string section are listed alphabetically.

Letters

From the General & Artistic Director

As Seattle Opera’s new General and Artistic Director, I am honored to welcome you to McCaw Hall to experience the world premiere of Jubilee. Tazewell Thompson has created an inspiring and compelling work that tells the story of the early years of the groundbreaking Fisk Jubilee Singers as they performed spirituals for audiences across the United States and the world.

I am delighted to be joining Seattle’s rich performing arts community. As I’ve said many times (and you will probably hear me repeat it): Seattle is an “Opera Town.” Your dedication, your curiosity, your enthusiasm, and your investment in opera is unique. I would like to share my excitement in leading the Seattle Opera and to express my gratitude to the remarkable Board of Directors of the opera for this prestigious opportunity. I would also like to thank Christina Scheppelmann—someone I have known for many years—for her support during this time of transition, and I am so appreciative of the warm welcome shown me by the entire staff of Seattle Opera.

This is a very exciting time to be coming to Seattle. The city’s cultural scene has tremendous momentum and there is a great appetite within the community to explore all that it has to offer. The symphony’s own appointment of Xian Zhang as their new Music Director is cause for great celebration for our Seattle Symphony partner and I know this will only strengthen the bonds between our organizations. I also recently had the pleasure of meeting the Seattle Art Museum’s new leader, Scott Stulen. I look forward to meeting and to collaborating with other arts organizations in the coming years.

Prior to coming to Seattle, I served as the Artistic Director at Opera Theatre of St. Louis where the company became a leader in producing new works. Over the sixteen years of my tenure, we presented world premieres by such composers as Huang Ruo, Tobias Picker, Ricky Ian Gordon, and Terence Blanchard. While I do have a keen interest in creating and presenting new works, I also have a passion for the great classics. Like many of you, I wear my heart on my sleeve when it comes to such titles as Madame Butterfly, La traviata, Tristan and Isolde, and just about anything by Mozart. Rest assured that my goal is to present compelling and balanced seasons of the new, the newer, and, of course, the core repertoire.

I look forward to meeting you, the opera-going community and the new-to-opera audience, at McCaw Hall and around this great city. As I am still finding my way around, please do not hesitate to share your favorite coffee places, restaurants, and suggestions for things to explore in Seattle. But for now, I invite you to enjoy Jubilee. I know this new opera will open your hearts to such spirituals as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Deep River,” and “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel.”

With sincerest thanks,

James Robinson

From the President

Welcome to the world premiere of Jubilee!

A whole evening of story and spirituals…forty of them! Many familiar, some less; all raw with emotion and loaded with the hope of heaven. Passionate. Lifechanging. Lifesaving. History making.

With their story, artistry, and passion, the Fisk Jubilee Singers changed the world. They were students, working hard to create the educational opportunities that would be the key to their futures. And in so doing, they created one of the first of the nation’s HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), graduates of which include American powerhouses like John Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois, Spike Lee, Thurgood Marshall, Toni Morrison, and Kamala Harris.

Are you seeing a link to opera? I certainly am.

Passion begets an energetic response. Opera is exciting. It draws people in. It changes minds and foments action. And the most effective medium for the expression of passion is the arts. The arts have power, importance, and permanence.

At Seattle Opera, we embrace the responsibility associated with the art we create. We recognize that our civic responsibility includes presenting stories to challenge, illuminate, and bring people together. If we do this well (and we do!), we will produce exciting live events that invite attendance and drive a reinvigoration of our urban center.

In this, we are delighted that Seattle Opera’s new General and Artistic Director, James Robinson, joins Seattle Art Museum’s new Director and CEO, Scott Stulen, and the Seattle Symphony Orchestra’s incoming Music Director, Xian Zhang in forming a new generation of leaders in the anchor arts institutions in the region. What a team! We look forward to a thrilling new chapter for the arts in Seattle.

As we eagerly greet the new, we applaud the firm foundation upon which it will be built. It is fitting that Christina Scheppelmann’s last production at Seattle Opera is a world premiere, as she has again and again forged new ground during her tenure here. Fittingly, her last is a first! And because her roots are deep in Seattle, in the language of her new appointment as General and Artistic Director of La Monnaie/De Munt in Brussels, we bid her au revoir, not adieu. We look forward to seeing her again soon!

Finally, a poignant change. The opera’s Board of Director and the larger community recently lost three of our best: Tom Allen, Bruce Johnson, and Tom Lemly. All were valued long-time board members, community champions, and wonderful humans who have left a lasting mark on our region’s institutions and hearts. We remember them with great affection and gratitude for the legacies they leave.

Like them, won’t you commit to our region’s arts? Be a page in this new chapter for Seattle Opera and the community. Here’s how: talk about Jubilee with your family, at the office, at social events. Come again and bring a friend—what a great introductory opera! Buy a subscription for the rest of the season for yourself or as a holiday gift, available now at seattleopera.org. Don’t miss a thing! And please remember Seattle Opera in your year-end generosity.

Thank you for all you do for Seattle Opera!

Lesley Chapin Wyckoff, President

Seattle Opera Board of Directors

Meet Seattle Opera’s New General & Artistic Director

Last month, James Robinson became Seattle Opera’s fifth General and Artistic Director.

We asked James why he’s eager to come to Seattle Opera, his philosophy for creating new works and his approach to the standard repertory, his drive towards artistic excellence, and what he enjoys doing in his free time.

Seattle Opera: What excites you about being Seattle Opera’s next General Artistic Director?

James Robinson: I’m excited because Seattle is an “Opera Town”! That’s not true for every American city. It’s in the city’s DNA, and I’m honored to be able to build on that rich tradition. I can’t wait to get to work creating art with and for the passionate audiences that have made Seattle Opera into the company it is today.

And Seattle is a spectacularly beautiful city. It’s a dynamic city—a growing and youthful city. I can’t wait to be a full-time member of the community.

Seattle Opera: How would you define your approach to artistic excellence?

James Robinson: Artistic excellence starts with getting the best people in place for their respective roles. Fortunately, in my thirty-plus years in this business, I’ve worked at the finest opera companies with many of the best conductors, designers, singers, and others. My number one goal is to maintain the high artistic standards Seattle Opera already has and add my experiences to that.

Seattle Opera: You’ve built your career, in part, on creating new works and taking on newer works. Tell us about your philosophy on commissioning new work.

James Robinson: When I started at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, I was passionate about raising the profile of the company. We began by looking at adventurous programming: creating new operas and doing productions of newer works that may have been neglected. We started the New Works, Bold Voices initiative and produced completely new works likes Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones. We also offered several contemporary works a second look. Tobias Picker’s Emmeline was one of those pieces, a revised and expanded version of Huang Ruo’s An American Soldier, and a new version of Ricky Ian Gordon’s The Grapes of Wrath, among many others.

We developed the New Works, Bold Voices in such a way to support creators who could embark on their first operas and write the stories they wanted to write. It was important to lay the groundwork with our local communities as the operas were being developed so they had some insights into the process, but also to generate enthusiasm. Lately, we have been working with community members to identify stories that they wanted to see on stage. That was an offshoot of New Works, Bold Voices called the New Works Collective. As I always say: Like politics, all arts are local. So, it’s vital to include the community during the development process on many levels.

Seattle Opera: Why is it important to create new and newer operas?

James Robinson: All operas were new at one point! I’d like to think that we’re not just in business of historic preservation. New works are vital to the art form in general and incredibly important to the development of audiences.

Seattle Opera: Then how do you balance the old with the new?

James Robinson: Familiarity breeds familiarity. Meaning audiences love the classics and they come back to what they know and admire, and there’s nothing wrong with that. I love them too. But I don’t think you can build an entire season with the traditional repertoire. You’d exhaust that rep really fast! Nevertheless, for many people those pieces are the entry points to opera. But it’s also a fact that new works bring in new people. You can’t ignore that new pieces can sell incredibly well. I’ve seen them outpace standard rep on many occasions at the box office. Balancing the traditional with the new must be approached strategically. And we must realize that one size doesn’t fit most. We have to offer many types of experiences.

Seattle Opera: Among the traditional repertoire, what are some of your favorites?

James Robinson: Where to start? I’m a huge Handel fan and consider Julius Caesar one of the greatest operas ever written. Madame Butterfly and La bohème still go right to my heart. Tristan is a personal favorite, especially Act Three. I think The Marriage of Figaro is an opera I can’t live without.

Seattle Opera: What would you say are opera’s biggest challenges?

James Robinson: I say this jokingly: Opera was invented in 1607; in 1608, opera was in crisis. Opera has always faced challenges, but it has soldiered on. More than that, it has continued to transform itself over the centuries and has always found new voices. Coming out of the pandemic, our largest task is just getting people to come back to the opera house. Opera isn’t an experience you can get on Netflix. It’s our job to remind people of the great time they’ll experience in the opera house. We must create buzz about every single project that’s done. But look, opera isn’t the only industry facing this dilemma. Symphony orchestras and theatre companies are struggling a bit, too. The movie industry and other forms of entertainment are going through the same thing.

Seattle Opera: On the opposite side of that coin, what excites you about opera’s future?

James Robinson: My goodness, live opera is one of the most spectacular experiences anyone can have! The great singing, the great music, the great stories all working together to make great LIVE performances. There is nothing like it.

Seattle Opera: What do you like to do when you’re not thinking about opera?

James Robinson: I’m an avid outdoor person. To stay sane, I work out at Orange Theory. There is an Orange Theory studio near the Opera Center! I’m also a runner. I’m big into cooking. My husband and I are both cooks, and my signature dish is veal osso buco. I also make a mean Moroccan tagine.

I’m a classic movie buff. Two of my favorites are A Place in the Sun and All About Eve. But now that I’m thinking about it, there are twelve other films that I could add to that list. Every Hitchcock film! And I like different types of music—everything from Wagner to Sarah Vaughan to Nirvana. My new obsession is the singer, Samara Joy.

Seattle Opera: What’s the last piece of music you added to your play list?

James Robinson: Philip Glass’s Piano Etudes performed by the composer. I read in The New York Times that Glass wrote the etudes to improve his own piano skills. At the same time, I was at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis directing Glass’s Galileo Galilei. Philip Glass filled my head, and I played the recording of the etudes over and over.

Seattle Opera: This is a tough question. What would you say is your favorite opera?

James Robinson: I hope this will not scare folks, but I just love Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress. I think it’s one of the most beautiful scores ever written and the moral fable it’s based on is so touching. It’s funny, poignant, and harrowing. It also has a perfect libretto. I think people think of Stravinsky as a thorny modernist, but this opera has such heart and emotion.

A Brief History of the Fisk Jubilee Singers

1863–1870

January 1, 1863: President Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people in Confederate-controlled areas.

January 9, 1866: On the grounds of a former Union Army hospital in Nashville, TN, Fisk Free Colored School opens.

August 22, 1867: Fisk Free Colored School incorporates as Fisk University.

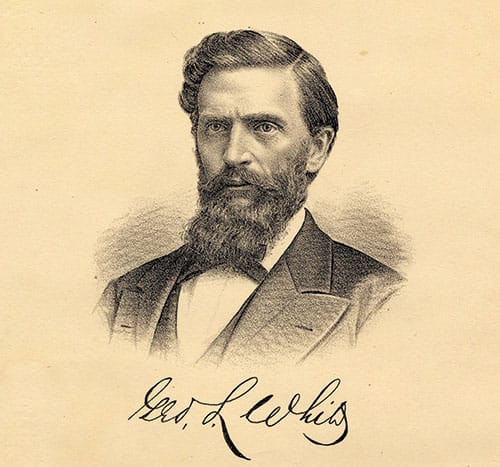

Spring 1870: Fisk Treasurer and self-appointed choir master George White, a white Northern missionary, organizes a group of singers to perform a cantata called Esther, the Beautiful Queen. The performance featured several future Jubilee Singers.

1871–1872: First Tour

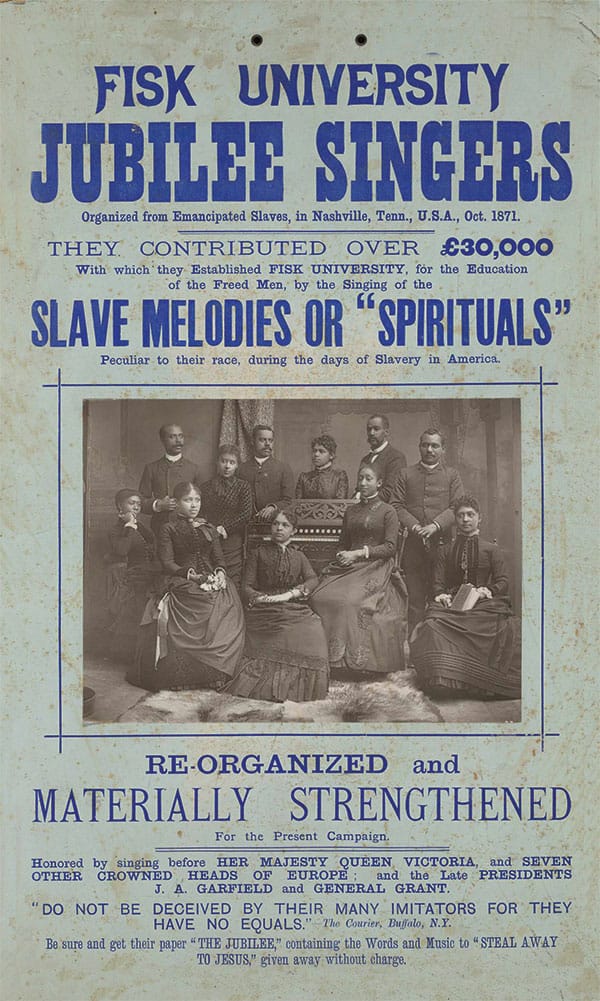

Fisk University faces bankruptcy and closure. White organizes a group of singers and (with Ella Sheppard) arranges traditional music for them to perform: African American spirituals. Originally created at informal gatherings of enslaved Africans, these spirituals—also known as field songs, secret songs, and plantation melodies—are some of the most significant bodies of American folksong.

October 6, 1871: Nine student singers embark on a fundraising tour of the Midwest and New England.

They call themselves the Fisk Jubilee Singers, in memory of the Jewish year of Jubilee (Leviticus 25:10: “And ye shall hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof: it shall be a jubilee unto you…”).

Early performances in Ohio and elsewhere raised hostility, as well as low attendance and raised little funds.

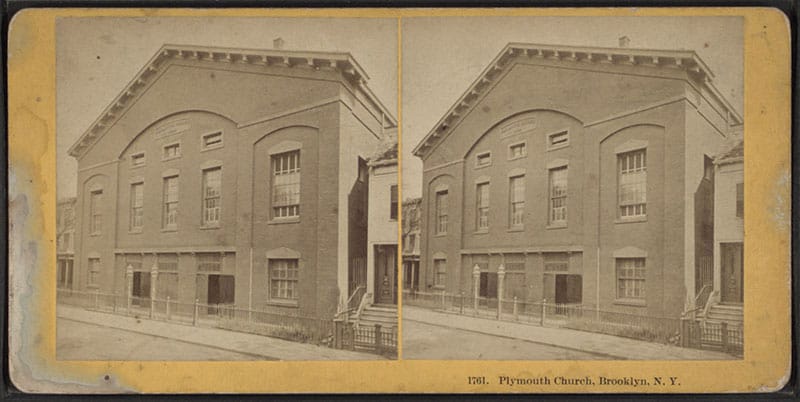

Reaching New York City, the singers perform at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn and Steinway Hall in Manhattan. These concerts were a great success.

1872-1873: Second Tour

The group performs at the World’s Peace Jubilee and International Music Festival in Boston and at the White House for President Ulysses S. Grant.

The Jubilees sail to Great Britain and sing throughout England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Prime Minister William Gladstone, Queen Victoria, and other dignitaries witness their performances.

1875-1878: Third Tour

The troupe performs in Chicago, Detroit, and other mid-western metropolises before heading back to Great Britain.

New Years Day 1876: Jubilee Hall, the first permanent structure of the university, is dedicated.

The singers tour Holland and Germany, where they perform for Kaiser Wilhelm II.

July 1878: Fisk University President E. M. Cravath disbands the original Fisk Jubilee Singers. It would not reform under the auspices of the school for 20 years; however, independent groups continue the name and the legacy.

The Original Jubilee Singers

Jubilee is the story of thirteen original members of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Discover who they were and the lives they lived before and after their time as Jubilee Singers.

Isaac Dickerson (1852–1900)

Born enslaved in Wytheville, Virginia, Isaac Dickerson’s earliest memory was the sale of his father to a slave trader. Dickerson was freed by his owner at the end of the Civil War and eventually made his way to Tennessee. Dickerson was among the first students to join the Fisk Jubilee Singers. During the ensemble’s tour of Britain, his oratory impressed the Dean of Westminster, who sponsored Dickerson’s education at the University of Edinburgh. Dickerson quit the troupe to pursue his studies. He lived the rest of his life preaching to the poor and downtrodden. He traveled through France, Italy, and Palestine.

Greene Evans (1848–1914)

Greene Evans was born into slavery and emancipated after the Civil War. He entered Fisk in 1868, paying his way by working as a groundskeeper and other odd jobs. Selected as one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, he traveled with the group on their first tour. Described as a “gifted extemporaneous speaker,” he was often called upon to address audiences. Quitting the ensemble at the beginning of the second tour, Evans entered politics, serving as a Memphis City Councilman and in the Tennessee General Assembly for two terms. Constantly hounded by white supremacists, he migrated north to Chicago.

Georgia Gordon (1855–1913)

Georgia Gordon was born in Nashville, Tennessee. In her youth, Gordon learned to read by studying the Bible. She entered Fisk in 1868, where she studied literature. Gordon set out with the Jubilees on two overseas tours but was sent home in disgrace after her affair with Frederick Loudin was discovered. After leaving public life, she married a minister and worked alongside him in the church. When her husband fell in love with a younger woman, Gordon died of a broken heart.

Benjamin Holmes (c. 1846–1875)

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Benjamin Holmes taught himself to read and write while apprenticed to a tailor. He was sold to a man in Chattanooga, Tennesee, where he worked as a hotel clerk. During the Civil War, Holmes volunteered his services as a valet to a Union Army general. Later, he entered Fisk University, where he studied Latin, history, and pedagogy. He toured America and Great Britain with the Jubilee Singers. As the group’s most eloquent spokesman, he advocated for better pay and—at the conclusion of the second tour—arranged his own farewell concert in London to benefit the singers, to the ire of ensemble leader

George White.

Jennie Jackson (c. 1852–1910)

Jennie Jackson’s parents were enslaved in Tennesse, in the household of Andrew Jackson; she, however, was raised in freedom. She joined the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1872. Her voice dazzled audiences. Jackson participated in the second and third tours. In Europe she was a sensation, much pursued by admirers. Fellow Jubilee Singer Mabel Lewis said that Jackson had no peace: “she would take her umbrella and beat her way along with it.” Jackson left the group due to ill health. Years later, she and other former members would organize vocal ensembles including the Jennie Jackson DeHart Jubilee Club.

Mabel Lewis (1860–1935)

Mabel Lewis was born to an enslaved woman from New Orleans who had an affair with a Frenchman. Her mother’s owner gave the girl to a Catholic general, who took her to New York, where he enrolled her in a convent. Eventually reared in Massachusetts by relatives of the general—a wealthy French family—she spoke French at home and was prohibited from having any interactions with Black people. At the age of ten, she ran away and was taken in by another White family. After hearing Lewis sing, this Massachusetts family arranged for her to receive an education and vocal lessons. The Jubilees were rehearsing nearby and invited her to join the troupe when they heard her impressive voice. She completed two tours. Later in life, she performed often at Fisk University.

Frederick Loudin (1840–1904)

Though born a free man in Ohio, Frederick Loudin experienced the sting of racism. After a short time in Philadelphia, where he married, Loudin went to Tennessee where he gained a reputation as a singer and music teacher. He joined the Jubilees, though he was considerably older and experienced than the other singers. After the troupe disbanded, he formed his own ensemble which circumnavigated the world, performing in India, China, Japan, and throughout Australia. With his earnings he moved back to Ohio, where he became a successful entrepreneur, inventor of the keychain, and manufacturer. At his death, he left his collection objets d’art, tapestries, and other mementos to Fisk University.

Maggie Porter (1853–1942)

Born in Lebanon, Tennessee, Maggie Porter was freed from slavery by her owner upon the publication of the Emancipation Proclamation. Porter attended a missionary school before entering the Fisk Free Colored School, where she became the leading diva of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Porter’s temperament matched her prima donna role and, at one point, she was kicked out; but the group, who needed her irreplaceable voice, took her back when she apologized for her unruly behavior. Porter performed in the first three tours, and briefly sang in Frederick Loudin’s ensemble before founding her own successful Original Jubilee Singers with her husband. Vowing to never set foot in the South, Porter’s only return to Nashville was in 1931 after the University convinced her to return to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Jubilees’ first tour. She died in 1942, at 89, the longest-living member of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers.

America Robinson (c. 1855–1920)

Born to enslaved parents in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, America Robinson’s entire family was sold when her owner ran into financial difficulty, being among the few fortunate families to remain together throughout bondage. She enrolled at the Fisk Free Colored School on the day it opened. A dedicated student, Robinson and her fiancé James Burrus were set to graduate when she was recruited to join the Jubilee Singers’ third tour. Her letters to Burrus stand as an account of that tour. When the tour ended, Robinson remained in Strasbourg to study music, French, and German. Although she would not make it to her commencement, Robinson would become the only Jubilee to earn a bachelor’s degree from Fisk University. Unfortunately, her romance with Burrus ultimately ended.

Thomas Rutling (1854–1915)

Born into slavery in Wilson County, Tennessee, Thomas Rutling was one of only four Fisk Jubilee Singers who remained with the company through all three pioneering tours. As a young table servant, Rutling often overheard his owners talking about the Civil War and relayed their news to his fellow slaves. At the end of the war, a Union Army surgeon recommended him to the president of the newly established Fisk Free Colored School. Rutling was a loyal follower of George White, who was impressed by his tenor voice. At the end of the third tour of Europe, he refused to return to America. He spent the rest of his life as a soloist and music teacher

in England.

Ella Sheppard (1851–1915)

Arranger & Assistant Conductor

Ella Sheppard was born enslaved on Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage plantation near Nashville, Tennessee. Her father purchased the family’s freedom then moved them to Ohio. Sheppard convinced two women to give her piano and voice lessons. After her father’s death, Sheppard supported her family by teaching the formerly enslaved. In 1868, she enrolled at the Fisk Free Colored School. Thanks to her musical skills she became assistant conductor of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Sheppard collected spirituals and wrote some of the arrangements used by the group. She participated in the first three tours. And as one of the most distinguished African American women of her generation, Sheppard was a tireless reformer and a confidant of Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.

Minnie Tate (1857–1899)

Minnie Tate was born free in Nashville, Tennessee. Her mother, a teacher, taught Tate to read and write. The youngest Jubilee Singer, she enrolled at Fisk at the age of 13. Tate was noted for her “astonishingly rich and pure voice.” She left the choir after the second tour, exhausted from the extensive traveling. Later, she sang with the ensemble organized by Frederick Loudin.

Edmund Watkins (D. 1929)

It is believed Edmund Watkins was born in Alabama. When very young, Watkins’ father was sold into slavery in Texas. His mother was a field hand—mother and son picked cotton together. After emancipation, his owner refused to pay him wages and continued to treat him as captive labor. Watkins escaped but was later captured while sneaking back to visit his mother and whipped—the only one of the Jubilee Singers to have been whipped. Watkins escaped a second time and worked his way through two years at Talladega College. Watkins completed two tours with the Jubilee Singers but stayed in England after the second tour. He feared he might be enslaved again if he returned to the South. Eventually, he moved to New York, where as an old man he was looked after by Erastus Cravath, the former President of Fisk University, and Cravath’s son, a Fisk University trustee.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in History & Memory

By Mark Burford, PhD

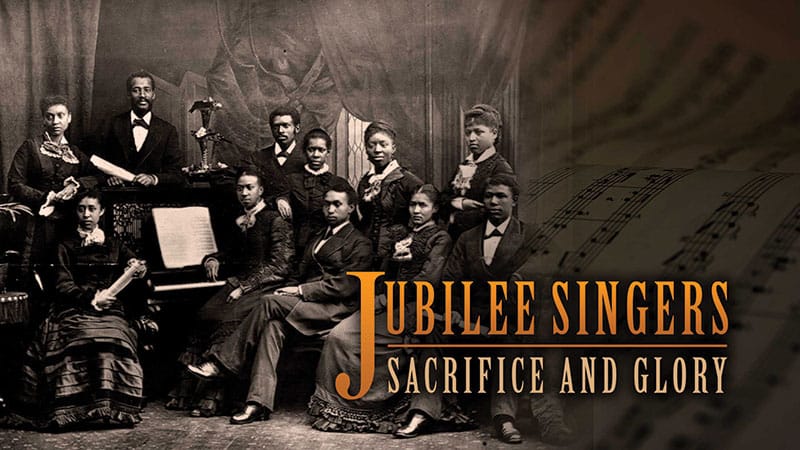

The metamorphosis of the Fisk Jubilee Singers from a Black college choir into the seminal group remembered today began with soul-searching “kitchen table” conversations.

The ensemble was formed in 1871 at Nashville’s Fisk University by its white music-loving Treasurer George White, who recruited nine of the school’s strongest singers, including pianist Ella Sheppard, to perform what Sheppard described as “the usual choruses, duets, solos, etc., learned at school.” Overhearing the singers swapping the religious folksongs of their enslaved ancestors—now known as spirituals—White was eager to fold these into the group’s repertory. Even before emancipation, abolitionists interpreted spirituals not only as testimony—underscoring the double meaning of such biblically-inspired lyrics as “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel” and “Tell Old Pharaoh To Let My People Go”—but also as evidence of African American religiosity, creative capacity, and humanity.

For White’s singers, however, spirituals were a cultural and historical inheritance still under negotiation. At first rejecting the idea outright (“We did not dream of ever using them in public”), then rehearsing, speculatively, on their own behind closed doors as they weighed the stakes of publicly performing songs that were both “sacred to our parents” and “associated with slavery and the dark past,” the young singers eventually decided, more momentously than perhaps even they understood, to share this musical heritage with the world. “It was only after many months that gradually our hearts were opened,” Sheppard remembered, “and we began to appreciate the wonderful beauty and power of our songs.”

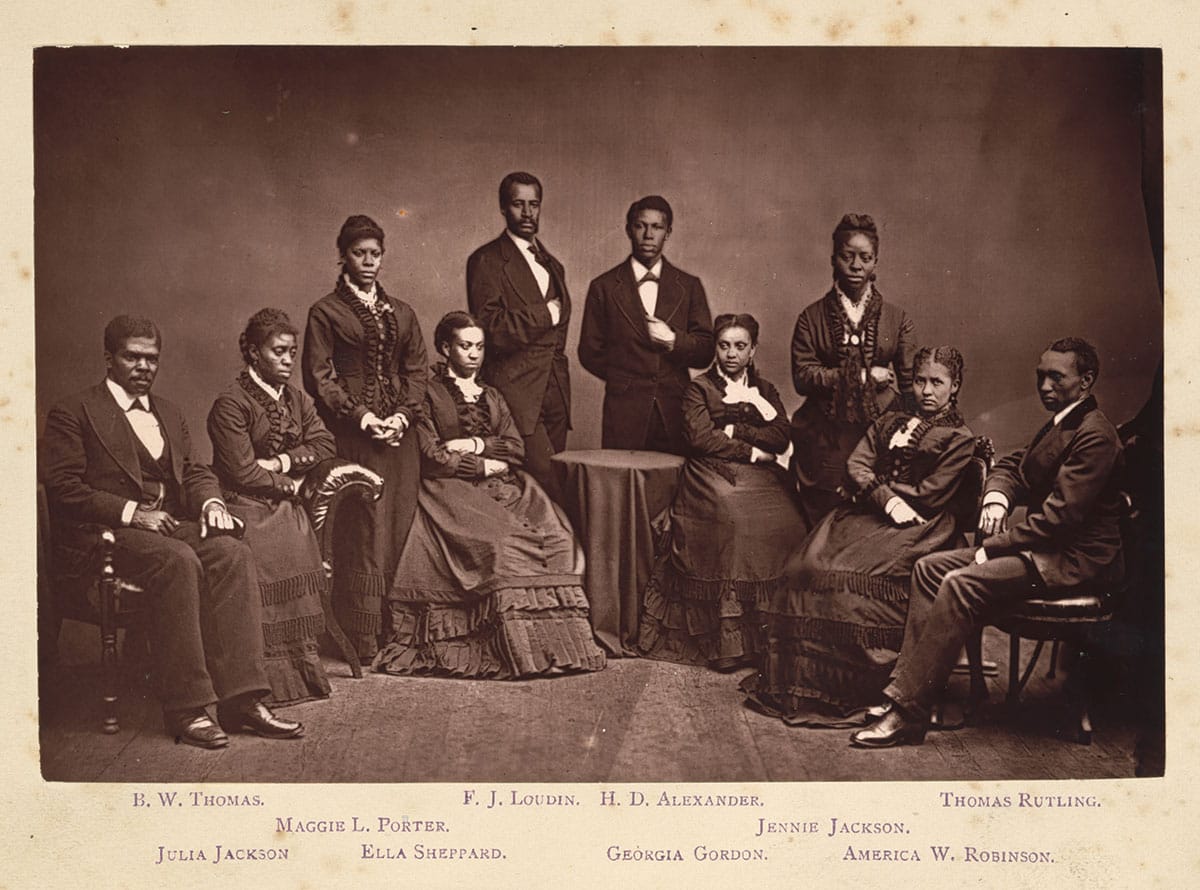

Catalyzed by this profound pivot—one that transformed “slave songs” into concert repertory and newly emancipated African Americans into influential transatlantic figures—the Fisk Jubilee Singers have become a fixed plot point in narratives about Black music. The group’s significance is grounded in their still resonant historical moment. Founded in 1866, The Fisk Free Colored School (incorporated as Fisk University the following year) was a product of the stubbornly misunderstood years of Reconstruction, the post–Civil War period of extraordinary African American opportunity and optimism, during which the country’s first historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were established to educate freedmen and their children. Of the nine original members, five Jubilee Singers—Maggie Porter, Thomas Rutling, Benjamin Holmes, Greene Evans, and Sheppard—had been born enslaved. The remaining four—Jennie Jackson, Minnie Tate, Mary Eliza Walker, and Isaac Dickerson—were the children of formerly enslaved parents. Seven of the nine were born in Tennessee.

The group’s early years, the topic of Tazewell Thompson’s play and now opera Jubilee—with vocal arrangements by Dianne Adams McDowell and orchestration by Michael Ellis Ingram—span their first three now-historic tours: an initial flurry of concertizing concentrated in the Northeast in 1871–72, launched as a desperate fundraising effort to save the near-bankrupt school; and two extended, wildly successful European sojourns later that decade. These involved a shifting roster of singers that came to include such substitutes and additions as Georgia Gordon, Edmund Watkins, America Robinson, Mabel Lewis, and Frederick Loudin. Despite the incessant and dispiriting indignities of touring while Black, their reputation and fame eventually took shape through a breakthrough endorsement from progressive Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward Beecher and their later reception by Queen Victoria in England and by cognoscenti in Germany, then popularly venerated as “the land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms.” Even as he drove the singers like a team of horses with a nonstop itinerary, White soon began paying them a salary—$500 for the first year and a raise to $700 annually for returning members—a not insignificant sum at the time. The estimated $150,000 earned during the three tours was enough to ensure Fisk’s solvency and build the school’s first permanent building, Jubilee Hall, which still stands today.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers forged their path in an age of empire and in counterpoint with prevailing assumptions of US popular culture. Like several other HBCUs, Fisk was launched and supported by the abolitionist American Missionary Association, which shaped the singers’ sense of purpose and immersed them in international networks of Protestant evangelism. This also endowed the Jubilee Singers with the added appeal of being heard as potential missionaries at a time of voraciously expanding interest among European powers in the joint projects of Christianizing and colonizing the African continent. At the same time, African American musicians on the concert stage were extraordinarily rare. “Black music”—an idea that was still in conceptual flux and was often rendered by blacked-up white men—was almost invariably experienced in the context of minstrelsy, nineteenth-century America’s most popular form of entertainment. The Fisk Jubilee Singers constantly navigated the expectations of perplexed white audiences and music critics accustomed to vaudeville’s comedic and histrionic fantasies of Blackness.

Instead, what listeners, often moved to tears, heard were spiritual settings sung, according to a steady stream of newspaper reports, with exquisite vocal blend, spellbinding dynamic control, and classicizing decorum. The eventual domination of spirituals on Jubilee Singers programs meant a new role for Sheppard, who was responsible for crafting the tunes into choral arrangements, making her White’s indispensable assistant music director. Exposing white audiences to spirituals and to Black dignity was a notable byproduct of the group’s work and, with this terrain opened, the late nineteenth-century explosion of spiritual-singing ensembles and copycat groups—some falsely passing themselves off as the Fisk Jubilee Singers—created what one music historian has described as a turn-of-the-century “jubilee industry.” But the literal invention of the concert spiritual by the Fisk Jubilee Singers is arguably their most tangible and lasting bequest. There is hardly a choir today, of any kind, that does not program choral spirituals, cultivated by an unbroken and artistically inventive tradition of Black arrangers and choral directors stretching from R. Nathaniel Dett, Hall Johnson, and Eva Jessye to Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, and Stacey V. Gibbs. Spirituals remain a pillar of HBCU–based choirs, including the still-active Jubilee Singers at Fisk.

In the final chapter of his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, scholar-activist W. E. B. Du Bois ruminated that whatever nineteenth-century audiences may have known about spirituals, “the world listened only half credulously until the Fisk Jubilee Singers sang the slave songs so deeply into the world’s heart that it can never forget them again.” Persevering with talent, courage, vision, indefatigable labor, personal sacrifice, and the precious legacy of their forebears, the Fisk Jubilee Singers saved their school, but, more importantly, they built a powerful legacy of their own, one that beseeches us, like the words they sing as the curtain falls: Do remember me.

Spirituals As a Living Tradition

By Mark Burford, PhD

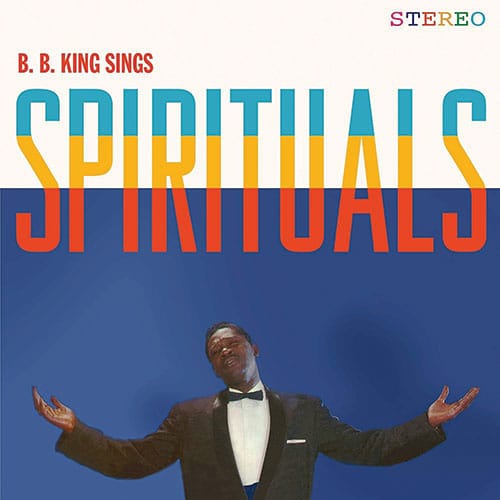

Beyond the concert stage, spirituals have maintained their relevance and cultural vitality through continuous reinterpretation by Black musicians in a range of stylistic idioms. In the 1930s, singer-guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe earned acclaim, though also criticism, for “swinging spirituals,” which some heard as a desecration of sacred Black heritage. But, over the years, a diverse array of Black jazz, rhythm and blues, pop, and folk artists—including Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan, Nat King Cole, B. B. King, Harry Belafonte, and Odetta, among many others—have made recordings, and in some cases entire albums, of familiar spirituals, delivering them in their respective musical dialect.

The well-known spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” exemplifies the mobility, malleability, and transmission of African American spirituals. Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson was fond of performing “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” in a mashup with “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess to demonstrate the Gershwin song’s indebtedness to Black southern traditions. In 1965, O. V. Wright recorded a brooding soul version of “Motherless Child.”

Decades later, Wright’s recording, in turn, became an inspiration for rapper Ghostface Killah, who sampled it on his 1996 cut “Motherless Child.” Hip-hop artists continue to tap spirituals for their symbolic meanings. In his 2009 song “Vanity Slaves,” Kendrick Lamar, reflecting on “slavery times,” observed how “Negro spiritual songs gave us some type of sanity.”

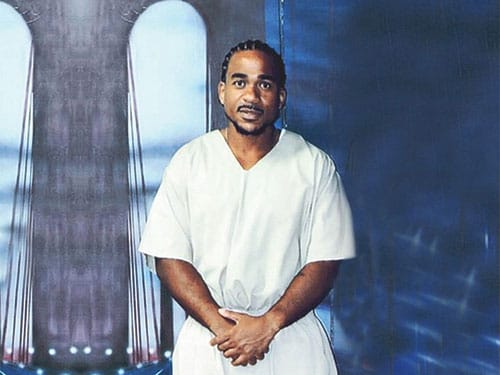

More recently, in 2021, incarcerated rapper and singer Max B released an album titled Negro Spirituals while still in prison. His explanation of its motivating concept conveys the ongoing investment in the spiritual as an enduring cultural and political touchstone: “I just wanted to be free. They got my body in captivity, but they ain’t got my soul. My mind was free and full of music.”

The Power of Jubilee

By Lauren Eldridge Stewart, PhD

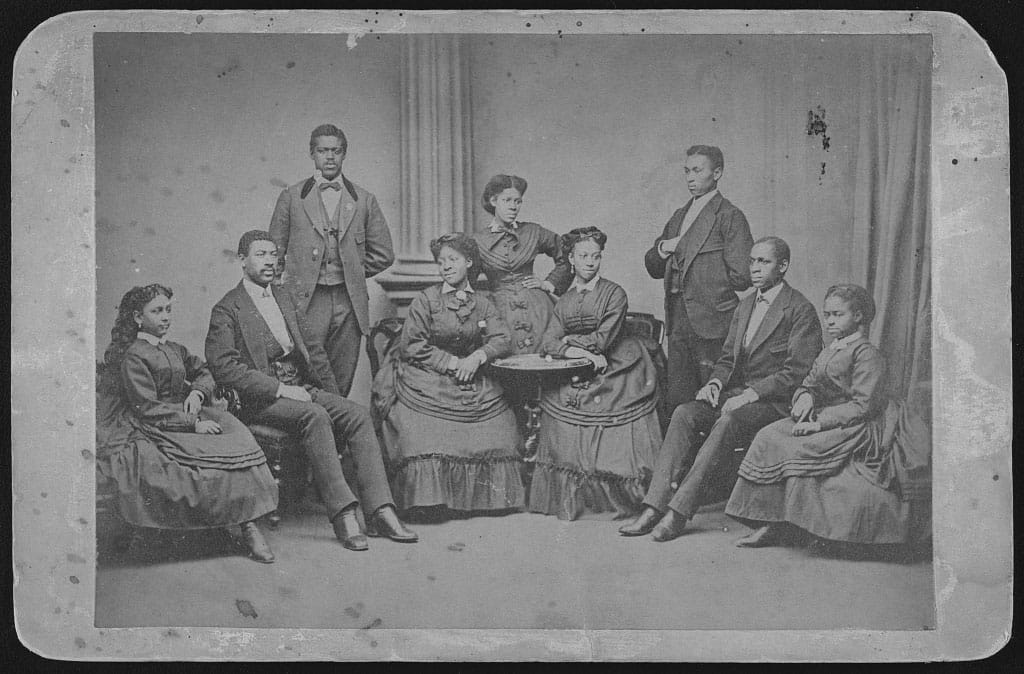

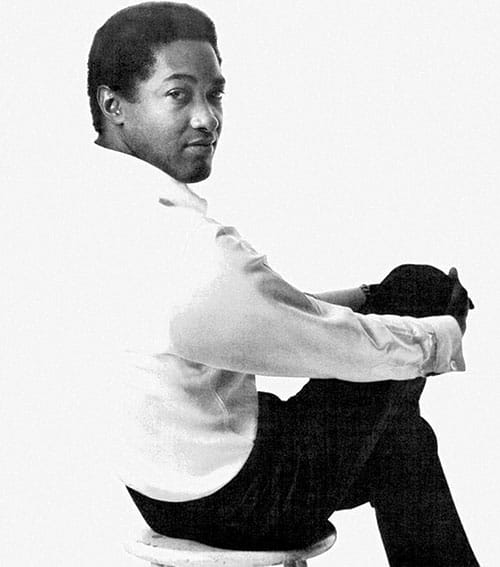

Above: A 1875 studio photograph of the Fisk Jubilee Singers

i’m going to sing ‘til the spirit moves in my heart.

In 1872, Dr. Cuyler, a reverend at the Thirteenth Street Presbyterian Church, upon hearing the Fisk Jubilee Singers in New York, said “I never saw a cultivated Brooklyn assemblage so moved and melted under the magnetism of music before. The wild melodies of these emancipated slaves touched the fount of tears, and gray-haired men wept like children.”

At this point in history, the repertoire of the Fisk Jubilee Singers primarily featured what W. E. B. Du Bois termed the “sorrow songs,” but also turned frequently to joy, and the type of energy that is infectious and inspiring, and that incentivized the early postbellum audiences to give toward the cause of education and to support the singers. When those audiences heard concertized spirituals, the subject matter, singing style, and song forms felt otherworldly. Through attending these performances, concertgoers not only felt deep emotion, but also found themselves in a space where they could express that deep emotion publicly.

What was it about this music that audiences found so compelling? And how have spirituals remained powerful to this day?

The concertized spirituals can be directly tied to folk spirituals, which evolved from a combination of the ring shout ritual and Protestant hymns during enslavement. The ring shout featured rhythmic movement in a circle, accompanied by call-and-response singing of sacred music and clapping. Much of what we hear today in the spirituals has evolved from this ritual: the repetition, the syncopation, and the coordination of movement and singing are all important aspects that have influenced many subsequent genres of Black music. There’s a beautiful duality and contrast in this music—the ring shout brings the kinetic energy and compels both the performer and the listener to move, while the hymn comforts and inspires.

The reverend’s statement also tells us a lot about the experience of attending a performance. The type of audiences that the ensemble performed for, audiences that would be both sympathetic to their cause and wealthy enough to contribute, were quite a bit removed from the impoverished realities of slavery. The spirituals painted a sympathetic picture for these listeners, animated and sung by stately-dressed Black people, people who embodied respectability and appeared deserving of education. The spirituals dramatize both Old and New Testament biblical stories often featuring ordinary people overcoming extraordinary circumstances. The lyrics of “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel” come to mind as a roll call of this type of story—

he delivered daniel

from the lion’s den

jonah from the belly

of the whale

and the hebrew children from the fiery furnace

then why not every man?

It is also evident from this stanza that these lyrics and the lyrics to many other spirituals were subversive and rather clever. The above lyrics quickly cite three separate stories as an argument for deliverance for every man. Deliverance can be understood in a variety of ways, but it is not a stretch to say that enslaved persons sang of a deliverance from slavery in a way that could be covered up in front of slaveholders as meaning a deliverance from sin.

it was grace that kept me, and it’s grace

that will lead me home

can’t you feel it move?

The repertoire that charmed audiences around the world in the late nineteenth century was rooted in the folk spirituals described earlier. The ensemble transformed these songs by locking in voice parts and tempo, adding drama through dynamic variation and vocal articulation, and presenting a rigorously rehearsed routine. The sound that began as an informal group tradition was meticulously shaped into a formal genre that appealed to moneyed donors. The combination of folk roots and educated polish moved audiences and garnered support across the northern United States and Europe.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ tours of Europe are particularly well-documented. Kira Thurman begins her profile of the Jubilee Singers’ 1877 tour of Germany with the account of Princess Victoria weeping at a performance and Ella Sheppard, the ensemble’s pianist, writing about it in her diary that night. The emotional power of their performances became legendary, leaving a paper trail of positive reviews. They played both small towns and big cities in Germany and the Netherlands that year, proving that their music was strong enough to overcome a language barrier.

This style of music remained in circulation long after the initial world tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. The ensemble, and several like them at other historically Black Colleges and Universities, continued the tradition, through evolutions of hairstyles, trends, and social justice movements. The ability of the spirituals to move people, to draw on something within them and pull them together, came to the forefront of public consciousness during the civil rights movement. Spirituals were sung during mass meetings, in a call-and-response style that focused the attendees on the plans being made and generated solidarity. The use of spirituals as freedom songs started in the mass meeting, spread to well-known folk singers like Odetta and Pete Seeger, and eventually became a feature in Black popular music of the 1960s and 70s. The soundtrack of those two decades, from Sam Cooke singing “A Change is Gonna Come” in 1964 to Donny Hathaway singing “Someday We’ll All Be Free” in 1973, resonates throughout subsequent social movements. The ethos of this music, from spirituals to freedom songs, echoes when people come together in search of answers and transformation—consider the footage of Black Lives Matter protests and demonstrations against police brutality. The spiritual as freedom song has become part of the DNA of the modern social movement.

The Jubilee Singers’ impact continues to the present day, although a contemporary writer might not describe these spirituals as having “wild melodies.” So much of the power in the Jubilee Singers’ sound emerges from the intricate harmonies and the warmth of blended voices. The arrangers throughout the ensemble’s history have been highly skilled and intentional about placing a lot of detail and nuance in the way traditional music is sung so that it constantly feels fresh. The arrangements of the spirituals have not remained static, and neither has the ensemble. With each new class of singers attending Fisk University, the Jubilee Singers are renewed. Their balance of tradition and innovation, looking back and moving forward, is a testament to the power of song.

Building Communities Through Music

By Glenn Hare

In a city like Seattle, musicians come together all the time to jam—to play familiar tunes or to learn new ones. A few times each month artists meet at Couth Buzzard Books and Community in Greenwood to celebrate Klezmer music, an Eastern European musical tradition that features the clarinet, violin, accordion, and other instruments like the tuba, and hammered dulcimer.

The Klezmer Jam is an initiative of The Rhapsody Project, a Seattle-based organization that honors, preserves, and teaches folk and roots music as well as empowers individuals and communities to use music as a tool for social change and cultural understanding.

“What differentiates us from other music organizations,” explains Joe Seamons, a co-founder and musician, “is that we not only play music and teach music but build community with music.”

At Couth Buzzard Sarah Larrson, Yiddish vocalist and percussionist, and Josh Rosard, accordionist, guide four first-time participant through Klezmer tunes. And as the musicians learn the notes and chords a new “ensemble” is formed and friendships are started. “Learning together and being together is what this is all about,” says Larrson.

A New Partnership

As a prelude to the world premiere of Jubilee, Seattle Opera joined with The Rhapsody Project to offer Face the Music, a virtual class that explores Black American music history, focusing especially on artists and ensembles that have been erased or hidden. Each session delved into the lives of artists like Bessie Jones (1902–1984), a gospel and folk singer credited with bringing the music of her community to a wider audience; Bert Williams (1874–1922), a Bahamian-born American entertainer who was among the leading vaudevillians of his era; and the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the ensemble that introduced spirituals to audiences across the US and the world not long after Emancipation.

In addition, to prepare students for a special student matinee performance of Jubilee on October 22, The Rhapsody Project and the opera co-developed and taught a curriculum used in Seattle schools and the Highline School District that introduced the history of spirituals and the legacy of the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

“We’re empowering young people to connect deeply with a cultural heritage they may or may not have experienced and understand it ongoing relevance,” explains Lady A, a Pacific Northwest teaching artist and performer, who co-wrote the curriculum.

“These activities underscore the shared commitment of our two organizations to appreciating American music history,” says Dennis Robinson, Jr., the opera’s Director of Programs and Partnerships. “Through them we hope to spark dialogues that will resonate throughout the community long after the world premiere of Jubilee.”

Back at the Klezmer Jam, between learning notes to “Dos Bisele Shpayz” (“This Little Food”) the conversation turned to borsht, schmaltz, kraut, and other Jewish foodways.

“I’ve listened to Klezmer music for a long time,” adds clarinetist Shaun Burley. “Tonight, I was the first time that I’ve actually played it with others. Best of all, I made new friends. Hopefully, I’ll see them again next month.”

Photo: At a recent Klezmer Jam, vocalist Sarah Larrson and accordionist Josh Rosard lead violinist Christopher Mena, keyboardist Fiore Grey, clarinetist Shaun Burley, and guitarist Jeff Treistman through several Yiddish tunes.

Reflections of Black Opera Administrators

Robert Babs and Symone Sanz are Black opera professionals at Seattle Opera. They both attended the Black Administrators of Opera Symposium that happened in Seattle in August. BAO is dedicated to the professional development, healing, advocacy, advancement, and collaboration of opera administrators who identify as members of the African diaspora working toward greater equity in the opera field. Robert and Symone share poignant memories from the gathering of more than 25 of their peers from around the country and Canada.

“For me, opening session and healing space was the most meaningful activity of the symposium. We spent nearly two hours introducing ourselves in detailed ways. Each person shared what brings them joy, how they came to opera, what they did in their roles, whatever else they felt meaningful at the time. It was time well spent and all the more impactful, to where we truly felt like we knew each other beyond our jobs and areas of professional expertise.