In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, March 27, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, March 29, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, March 30, 2025, at 2:00pm

Juraj Valčuha conducting

Johannes Brahms

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 77 (1878)

Allegro non troppo

Adagio

Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace

Gil Shaham

Intermission

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Opus 93 (1953)

Moderato

Allegro

Allegretto–Lento–Allegretto

Andante–Allegro

Juraj Valčuha’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half of the program is Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10, written shortly after the death of Joseph Stalin. The first movement broods darkly, while the relentless Scherzo is equally exhilarating and terrifying. In the final movements, the composer inserts himself through the first prominent appearance of his recurring note-name monogram, D-S-C-H.

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 77

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Composed: 1878

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1915. Henry Hadley conducted with Efrem Zimbalist as soloist. Most recent—June 2021. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted with Augustin Hadelich as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 35 mins

For most of his life and about a half-century after his death, Johannes Brahms was considered a superb craftsman but something of a fusty relic. Now that we don’t adhere to the strict binaries that polarized music fans during the so-called War of the Romantics—a mostly bloodless, decades-long ideological battle that required concertgoers to declare their loyalty to either radical Team Wagner or conservative Team Brahms—we can see Brahms in all of his complexity.

Brahms was at once an antiquarian and an experimentalist, a conservative classicist and a singular Romantic. One of his more surprising champions, the composer Arnold Schoenberg, delivered a lecture in 1933, 100 years after Brahms’s birth, titled “Brahms the Progressive.” In this appreciation, which Schoenberg revised and expanded in 1947, the cutting-edge serialist reclaims “Brahms, the classicist, the academician,” calling him “a great innovator in the realm of musical language.”

Brahms was a brilliant pianist, but unlike Beethoven, Mendels-sohn, and Mozart, he couldn’t play the violin. Fortunately, he was close friends with Joseph Joachim, the Hungarian-born violinist, composer, and conductor who ranks among the most influential musicians of the 19th century. Although Joachim was only two years older than Brahms, he was already an established performer when he befriended the young Hamburg native in 1853. A child prodigy, Joachim was mentored by Felix Mendelssohn; it was his 1844 performance of Beethoven’s violin concerto, under Mendelssohn’s baton, that cemented the work as a staple of the repertoire. Through Joachim, Brahms met Robert and Clara Schumann, who promoted him tirelessly.

In summer 1878, when Brahms began working on his violin concerto, he was 45 years old, with two formidable symphonies and one piano concerto under his belt. Despite his lack of proficiency on violin, he wasn’t especially anxious about the project. His models were the same two violin concertos that inspired and intimidated most of his serious contemporaries: Beethoven’s urgently expressive contribution to the genre, championed by both Joachim and Felix Mendelssohn, and Mendelssohn’s lustrously lyrical one. Joachim, whose own Hungarian Concerto remained popular, was generous with his time and talent. For the rest of that year, the two men composed by correspondence, with Joachim offering technical advice, rewriting tricky passages, and even composing the only cadenza, in the first movement.

Brahms was a relentless perfectionist and he irritated Joachim by soliciting feedback only to ignore it. More annoying still, Brahms announced that he was deleting the two middle movements, which Joachim had been diligently practicing for weeks. “I’m writing a wretched adagio instead,” the composer explained with his usual irony.

He finished the concerto by the deadline, but just barely. The four-movement work that he and Joachim had originally envisioned now comprised a more conventional three movements, but it was far from conventional in most other respects. His loyal ally Joachim pronounced it a masterpiece, but few of their peers seemed to agree. Most people were put off by its daring, destabilizing rhythms and its oddly egalitarian orchestration. The wider public was simply not ready for a symphonic concerto in which the soloist and orchestra are equal partners, not star and supporting players, or rivals.

The 1879 premiere was disappointing. The Leipzig audience was politely underwhelmed. In fact, for decades after the composer’s death, the violin concerto was widely dismissed as a failed experiment: dry, severe, pointlessly difficult. The conductor Josef Hellmesberger famously dubbed it “a concerto not for, but against, the violin.” Brahms was so dismayed by its reception that he destroyed his second violin concerto before allowing anyone to hear it, and he never composed another.

The Music

The opening Allegro non troppo builds slowly to its lyrical climax, with numerous Romani-style excursions in honor of its dedicatee’s Hungarian roots, where such folk music was common. This unusually long movement begins in its home key—pretty, pastoral D major—but the solo violin, accompanied by timpani in an obvious nod to Beethoven, enters in a deliberately jarring D minor.

The central Adagio, with its blissful oboe melody suspended over gossamer wind harmonies, is dreamy, delicate, and anything but “wretched.” The oboe tune elicits the solo violin’s variation, and the new idea inspires a stormy middle section (in minor) before circling back to serenity.

Brahms marked the finale “Allegro giocoso ma non troppo vivace,” (jocularly cheerful, but not too lively). This lusty quasi-

rondo is a technical terror, peppered with tricky double-stops, harrowing rhythmic tension, and Hungarian fireworks. Even Joachim had to perform it several times before he felt comfortable with the breakneck passagework. “One enjoys getting hot fingers playing it,” he later declared, “because it’s worth it.”

—René Spencer Saller

Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Opus 93

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg

Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1953

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1969. Peter Erös conducted. Most recent—April 2022. Klaus Mäkelä conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo (2nd flute doubling 2nd piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn (doubling 3rd oboe), 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet (doubling 3rd clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon (doubling 3rd bassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, tambourine, cymbals, tam-tam, snare drum, bass drum, and xylophone), and strings

Duration: About 53 minutes

The longest gap in Dmitri Shostakovich’s symphonic output was the eight years between his Symphony No. 9 in 1945 and No. 10 in 1953. In between, he was denounced by Soviet authorities for the second time, accused of “formalism”—writing music without a proper social purpose. He lost his teaching posts at the Leningrad and Moscow conservatories and many of his pieces were blacklisted. He turned to writing film music for money and composed grand “politically correct” (in the original sense) cantatas with an eye toward rehabilitation.

Then on March 5, 1953, Joseph Stalin died, and soon censorship lessened, ushering in what became known as the Khrushchev Thaw. That summer, Shostakovich set to work on his 10th Symphony, finishing the first movement on August 5 and the last on October 25. Some parts may have earlier origins—a colleague said he showed her portions in 1951, and an unfinished violin sonata from 1945 explored similar material. The symphony was premiered on December 17, 1953, by the Leningrad Philharmonic.

Solomon Volkov’s 1979 book Testimony, which purports to be Shostakovich’s memoir smuggled out of the Soviet Union, describes the symphony as a “portrait of Stalin and the Stalin years,” with the second movement Scherzo specifically intended as an effigy of the dictator himself. The authenticity of the posthumously published book, which paints Shostakovich as a secret dissident writing cryptic protests, is widely disputed, particularly by biographer Laurel E. Fay and the late musicologist Richard Taruskin. Certainly Shostakovich recognized absurdities in Soviet ideology and at times satirized and pushed against then in his music. However during his life, he was viewed in both Russia and the West as a loyal Communist who twice fell out of favor (not uncommon under a mercurial regime), and never as an anti-government artist.

A 1969 program note for the San Francisco Symphony was typical in describing Shostakovich as composing “music he felt served the ideal of his country, which he seems whole-heartedly to have accepted as his own ideal.” Discussing the 10th Symphony for its first San Francisco performance a decade before Testimony, that writer saw no portrait of Stalin, only noting that the piece’s tragic tone conflicted with the Soviet mandate for optimism, and concluding that the work’s obvious musical merit forced the censors to accept it anyway.

Indeed, in April 1954, the Composer’s Union combed through the 10th Symphony and reluctantly approved it. Listeners today might reasonably intuit that its grimness reflects the abuse and terror Shostakovich experienced under Stalinism, but to take it as a subversive statement, one must consider whether something that slipped past both Soviet authorities and American commentators at the time can be meaningfully subversive at all.

The Music

The first movement is a magnificently paced Moderato that builds tension in a single-minded expanse through a series of harrowing climaxes. It begins in the cellos and basses and grows into a string chorale that is somehow both calm and deeply uneasy at the same time. A winding clarinet solo feels like the first utterance of what had so far only been internal; a horn cry introduces fuller symphonic writing, before falling back with a quiet brass chorale and the lonesome clarinet again. Then a new element: a wry little flute solo, accompanied by plucked strings. Slowly this builds up to an overwhelming fortissimo, and just when it seems like there’s no more room to crescendo, Shostakovich brings in military drums and then three devastating crashes on the tam-tam. He follows with an organ-like falloff before touching on the opening again, now in the bassoons. This time, instead of clarinet, the movement dissolves in the eerie whistle of piccolo and thump of timpani.

The seething scherzo reworks material from the first movement at about five times the speed in one-sixth the time. Pages of fortissimo rush across the conductor’s desk as the orchestra drives relentlessly forward. In a stomach-dropping instant, the strings are hushed into near silence without breaking their frantic flight. They re-crescendo to a savage cutoff.

The third movement, Allegretto, cautiously peaks out to look around. Along comes an ironic parade, with piccolo and flute accompanied by timpani and triangle. The pitches spell out an emblem—D-S-C-H. “Dmitri Schostakowitsch” (in German spelling, where S means E-flat and H means B-natural). It became a recurring hallmark in his later works, and appears prominently here for the first time.

There’s a second name hidden in lonesome horn calls: E-La-Mi-Re-A. “Elmira” (in a mix of German and French note names). She was Elmira Nazirova, a Jewish Azerbaijani pianist and composer who had studied with Shostakovich in the late 1940s. They reconnected when he visited Baku in 1952, and in April 1953, he pursued a one-sided emotional affair with her by mail. She accepted his invitation to attend the symphony’s first Moscow performance, and he gave her an autographed copy of the score. Between its pages, their musical monograms mingle and slip apart.

The last movement, like the first, begins with cellos and basses. A familiar color, but this time with different, vaguer music. Then we hear the oboe—an instrument hardly used lyrically in the previous movements, but one that often appears in Shostakovich’s music at moments of transformation or rebirth. From the Andante introduction, a flute solo bridges into a darting Allegro, channeling a lively klezmer wedding dance. Yet its materials are not so different from those of the terrifying Scherzo, just as the triumphant D-S-C-H ending recontextualizes elements from the first and third movements, turning calamity into catharsis.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

A previous version of this note appeared in the program book of the Melbourne Symphony.

About the Artists

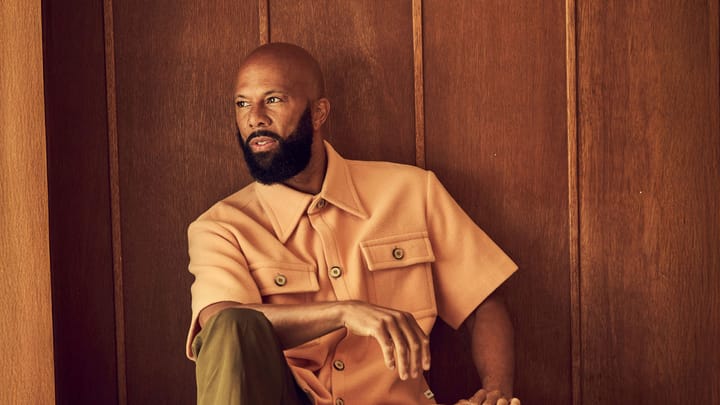

Juraj Valčuha

Juraj Valčuha has been music director of the Houston Symphony since June 2022. He was previously music director of the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples from 2016 to 2022, chief conductor of the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della Rai from 2009 to 2016, and first guest conductor of the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra.

Valčuha’s recent engagements include the Chicago Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Orchestra dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia, Orchestre National de France, and Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra. On the opera stage, he has led productions at the Bavarian State Opera, Deutsche Oper Berlin, and Opera di Roma. He has also appeared with the New York Philharmonic, Pittsburgh Symphony, Berlin Philharmonic, Dresden Staatskapelle, Munich Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, BBC Symphony, London Philharmonia, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Filarmonica della Scala, and NHK Symphony.

Born in Bratislava, Slovakia, Valčuha studied composition and conducting in his hometown as well as in Saint Petersburg and Paris. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in May 2013 as a Shenson Young Artist.

Gil Shaham

Gil Shaham regularly appears with the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Israel Philharmonic, and has had multi-year residencies with the Montreal Symphony, Stuttgart Philharmonic, and Singapore Symphony. Recent highlights including performances and a recording of Bach’s complete sonatas and partitas for solo violin, as well as recitals with his longtime duo partner, pianist Akira Eguchi.

Shaham has more than two dozen recordings to his name, earning a Grammy Award, a Grand Prix du Disque, Diapason d’Or, and Gramophone Editor’s Choice. Many of these recordings appear on Canary Classics, the label he founded in 2004. His 2016 recording 1930s Violin Concertos Vol. 2 as well as his 2021 recording with the Knights were nominated for Grammys.

Shaham was awarded an Avery Fisher Career Grant in 1990 and in 2008 received the Avery Fisher Prize. In 2012, he was named Instrumentalist of the Year by Musical America. He plays the 1699 “Countess Polignac” Stradivarius and performs on another Antonio Stradivari violin, ca. 1719, with the assistance of Rare Violins In Consortium, Artists and Benefactors Collaborative. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in July 1990 and became a Shenson Young Artist in 2005.