In This Program

The Concert

Wednesday, April 9, 2025, at 7:30pm

Martin James Bartlett piano

François Couperin

Les Baricades mystérieuses

from Second livre de pièces de clavecin (ca. 1717)

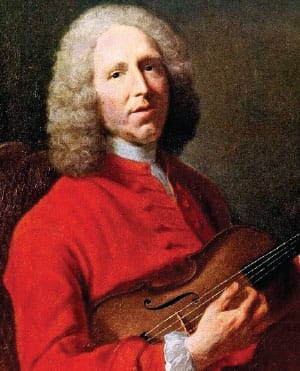

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Gavotte and Six Doubles from Suite in A minor, RCT 5 (ca. 1726)

Robert Schumann

Kinderszenen, Opus 15 (1838)

Von fremden Ländern und Menschen (Of Foreign Lands and People)

Kuriose Geschichte (Curious Story)

Hasche-Mann (Blind Man’s Bluff)

Bittendes Kind (Pleading Child)

Glückes genug (Happy Enough)

Wichtige Begebenheit (Important Event)

Träumerei (Dreaming)

Am Kamin (At the Fireside)

Ritter vom Steckenpferd (Knight of the Hobbyhorse)

Fast zu ernst (Almost Too Serious)

Fürchtenmachen (Fearmongering)

Kind im Einschlummern (Child Falling Asleep)

Der Dichter spricht (The Poet Speaks)

Robert Schumann

(trans. Franz Liszt)

Widmung, Opus 25, no.1 (1840/48)

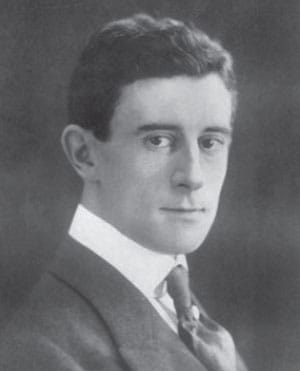

Maurice Ravel

Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899)

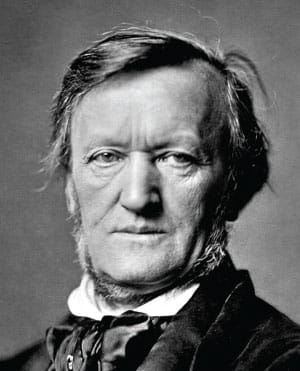

Richard Wagner

(trans. Franz Liszt)

Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde (1859/68)

Maurice Ravel

La Valse (1920)

This program is performed without intermission.

Program Notes

Les Baricades mystérieuses

from Second livre de pièces de clavecin

François Couperin

Born: November 10, 1668, in Paris

Died: September 11, 1733, in Paris

Work Composed: ca. 1717

François Couperin was the most illustrious member of a musical dynasty that flourished from the 17th century through the 19th. For 170 years, one Couperin after another served as organist at the Church of St. Gervais in Paris. Some were also appointed musiciens du roi, including François, who earned the sobriquet “Le Grand.” He married into relative wealth, and in 1690 he obtained a royal privilege to print and sell music. This enabled him to publish a good-sized catalogue that would include organ works, motets (and some secular songs and ensembles), pieces of chamber music, and a large body of harpsichord music. He published his principal harpsichord compositions in four volumes, each containing a handful of suites (ordres, he called them), their movements headed by often cryptic titles.

Les baricades mystérieuses, from the sixth ordre in his Second livre de pièces de clavecin (Second Book of Harpsichord Pieces, 1717), is a rondeau—a principal paragraph of music returns a number of times, its reiterations separated by novel material that is nonetheless related in its melody and figuration. In this enchanting movement, Couperin creates a broken-chord texture rich in harmonic suspensions that maximizes the harpsichord’s resonant possibilities. What does the title mean? The Couperin biographer Wilfrid Mellers hewed to a technical explanation, “the continuous suspensions in lute style being a barricade to the basic harmony.” Other commentators have opined that it suggests winemakers rhythmically stomping grapes (une barrique is a barrel), the barrier between life and death (or past and future), or perhaps even something involving sexual liaison or abstention.

Gavotte and Six Doubles from Suite in A minor, RCT 5

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Baptized: September 25, 1683, in Dijon, France

Died: September 12, 1764, in Paris

Work Composed: ca. 1726

Although Jean-Philippe Rameau’s solo harpsichord music constitutes a small niche of his oeuvre when compared to his stage works, it is an impressive chapter in the output of the French clavecinistes, the harpsichordist-composers (like Couperin) who produced a large repertoire of suites, mostly comprising dances and character pieces, from the mid-17th century until the French Revolution. Rameau’s three collections of harpsichord pieces were published in 1706, 1724, and ca. 1729/30. The Gavotte and Six Doubles appears in the last of these, the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin, standing as the final movement of its imposing first suite.

The gavotte was a commonly encountered courtly dance, usually more cheerful than this one is; but it also existed in a slower style called the gavotte tendre, of which this is an example. What make this expanse extraordinary are the ensuing variations (or doubles, as Rameau calls them), each working out the implications of a different sort of figuration while embellishing the main melody. This piece does not sound very French. Handel comes to mind instead, and particularly the third of his so-called “Eight Great Suites” for the harpsichord, an imposing work in D minor that includes an Air with five variations that unroll much as Rameau’s do, and with largely parallel technical demands. Handel published his suites in London in 1720, and Rameau doubtless seized on them by the time he came to write his own Suite in A minor. It is no stretch to consider this Gavotte with doubles either an homage to Handel or an act of one-upmanship, since Rameau wrote a further variation beyond Handel’s five.

Kinderszenen, Opus 15

Robert Schumann

Born: June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony

Died: July 29, 1856, in Endenich, Germany

Work Composed: 1838

Robert Schumann was practically without peer when it came to telling stories through instrumental music, and especially telling stories to the unbiased ears of children. His piano works include a great deal of program music geared to young listeners, some of it crafted to be within reach of student pianists, including collections such as his Kinderszenen (Scenes of Childhood), Album for the Young, and Three Piano Sonatas for the Young. Igor Stravinsky, in his book Retrospectives and Conclusions (1969), said, “Schumann is the composer of childhood . . . both because he created a children’s imaginative world and because children learn some of their first music in his marvelous piano albums.”

Of the three collections mentioned above, Schumann composed the latter two for the use of his own children, whereas Kinderszenen was born of a distinct impulse. Joan Chissell, in her classic study of Schumann’s piano music, observed: “Despite technical simplicity, the 13 pieces of Kinderszenen are an adult’s recollection of childhood, for adult performers,” echoing Schumann’s own description of them, to his fellow composer Carl Reinecke, as “reflections of an adult for adults.” In March 1838, Robert wrote to his beloved Clara Wieck, not yet his wife: “Whether it was an echo of what you said to me once, ‘that sometimes I seemed to you like a child,’ anyhow, I suddenly got an inspiration, and knocked off about 30 quaint little things, from which I have selected 12 [sic] and called them Kinderszenen. . . . Well, they all explain themselves, and what’s more are as easy as possible.” In fact, his set comprised 13 pieces, not 12. The rest of the “about 30” pieces he wrote in that spurt of creativity live on, since he incorporated them years later into other collections.

Widmung, Opus 25, no.1

Robert Schumann (trans. Liszt)

Work Composed: 1840 (trans. 1848)

We move ahead to 1840, a year in which Robert Schumann unleashed a torrent of lieder—nearly 170 of them, setting texts by German Romantic poets. His “Year of Song” was indeed miraculous, yielding not only small song-sets but also several of his most enduring cycles and collections: the two Liederkreis, Frauenliebe und -leben, and Dichterliebe. In March and April of that year he produced a set of 26 songs envisaged as a gift for Clara, and he presented them to her that September, on the day before their marriage. The published score was headed with the inscription Seiner geliebten Braut (to his beloved bride). He called the collection Myrthen (Myrtles), the reference being to sprigs used for wedding finery to symbolize the bride’s chastity. Themes of nature and the fulfillment of love run through the collection, and they are announced in the opening item, “Widmung” (Dedication), to a poem by Friedrich Rückert, which remains one of his most cherished songs.

Franz Liszt published his solo piano transcription of “Widmung” in October 1848. We might do well to think of it as an interpretation rather than a strict transcription, since Liszt expands the original structure and adorns the whole with keyboard filigree. The following year, Reinecke issued piano transcriptions of eight songs from Myrthen, including this one, which Schumann himself edited; and in 1873, Clara Schumann published her own very literal piano version. The composer wrote to Reinecke: “Basically, as you suspect, I am not a fan of song transcriptions and the Liszt ones are a real annoyance for me. Under your hands, however, I feel quite at ease, and this is because you understand me like few others, pouring the music into another vessel, as it were, without pepper and spice à la Liszt.” The Liszt transcription became a classic, while the Reinecke and Clara Schumann versions are forgotten.

Pavane pour une infante défunte

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1899

Maurice Ravel, whose 150th birthday was celebrated last month, was a capable pianist, but as a student at the Paris Conservatory he did not display the keyboard panache required of a top-flight concert virtuoso at the turn of the 20th century. He left the school in 1895 but returned in 1897 to study composition with Gabriel Fauré and counterpoint and fugue with André Gédalge, both of whom he acknowledged as formative mentors. He failed (after five attempts) to secure the Prix de Rome, the distinction that served as a seal of approval for emerging composers. He didn’t need it. Already in the late 1890s he was making a mark.

He apparently unveiled his Pavane pour une infante défunte at the socially stratospheric Paris salon of the Princesse de Polignac in 1899, although its public premiere (by his lifelong friend Ricardo Viñes) would not take place until a few years later. Its title is often rendered in English as “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” but it’s a poor translation. Ravel pointedly uses the word “infante” rather than “princesse,” and there is no reason not to employ the closer translation of “Infanta,” redolent of a rather exotic form of Iberian aristocracy. In fact, the title was selected for the sound of the words rather than their meaning. The critic Alexis Roland-Manuel quoted him as insisting, “When I put together the words that make up this title, my only thought was the pleasure of alliteration.” A piece that everybody recognizes instantly, its emotional coolness and restrained melancholy lend it a unique personality.

Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde

Richard Wagner (trans. Liszt)

Born: May 22, 1813, in Leipzig, Saxony (Germany)

Died: February 13, 1883, in Venice, Italy

Work Composed: 1858–59 (trans. 1868)

Richard Wagner’s earliest operas amalgamated more-or-less standard traditions of German Romantic opera (as codified in the works of Weber, Marschner, and others) and French Grand Opera (typified by Meyerbeer and his contemporaries in Paris). As his career progressed, he moved increasingly toward realizing his concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, a work synthesized from disparate artistic disciplines, including music, literature, the visual arts, ballet, and architecture—an ideal he reached fully in Tristan und Isolde.

Consonance and dissonance reside in close quarters here, lending an uncanny sense of ambivalence and yearning through the opera’s immense, chromatic span. Liebestod (Love-Death) is today understood to refer to the opera’s final section, in which the heroine expires in ecstasy over her lover’s corpse. Wagner himself connected that title to the opera’s prelude and called the final scene Verklärung (Transfiguration). But, in popular usage, the name Liebestod took over for the ending, and it was absolutely cemented when Liszt placed the title at the top of his magisterial piano transcription of that conclusion, published in 1868.

Liszt possessed considerable authority on matters Wagnerian: in addition to being an ardent champion of Wagner’s works, he would also become his father-in-law. When Wagner got romantically involved with Liszt’s daughter Cosima, in 1864, they were both married, she to the Liszt pupil Hans von Bülow. Richard and Cosima married in 1870, after Bülow granted her a divorce and Wagner’s first wife died. Bülow conducted the world premiere of Tristan und Isolde in 1865—two months after Cosima gave birth to a daughter. For a while Bülow claimed that he was the baby’s father, but it soon became clear that Wagner was the real father. The child was named Isolde.

La Valse

Maurice Ravel

Work Composed: 1920

As early as 1906, Ravel was thinking about composing a tribute to Johann Strauss, Jr., the famous “Waltz King” of 19th-century Austria, but he didn’t get much farther than selecting its title: Wien (Vienna). Years passed and Ravel was continually distracted by other projects, and then Europe crumbled under the calamity of World War I, during which he served as a driver in the motor transport corps and witnessed the horror of combat up close. When the War ended, Ravel retained his admiration for the waltz as a musical genre, but its sociological implications had changed. What had formerly signified joie de vivre was tainted by national hubris and international catastrophe. La Valse, finally composed in 1919–20, therefore reveals itself, ever so gradually, to be a danse macabre. The interval of the tritone (the augmented fourth or diminished fifth), historically signifying some diabolical connotation, is shot through the melodies, yielding a bitonal sense of something being out of kilter. In the final minutes we are forced to accept that the waltz has run seriously amok—irretrievably so at the conclusion, which is nothing short of violent, terrifying, and bitterly final.

Ravel envisaged La Valse as a ballet score for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, but when he and his pianist-colleague Marcelle Meyer played it in a two-piano arrangement for him, the great impresario said (according to Francis Poulenc, who was present), “Ravel, it’s a masterpiece, but it’s not a ballet. . . . It’s the portrait of a ballet, a painting of a ballet.” The work sometimes serves as a ballet score today, but is more often heard as an orchestral showpiece, occasionally in Ravel’s two-piano setting, and more rarely in the composer’s solo-piano version of 1920.

—James M. Keller

About the Artist

Martin James Bartlett

Martin James Bartlett was the inaugural recipient of the Prix Serdang in 2022, a Swiss prize curated by Rudolf Buchbinder. Highlights of Bartlett’s 2024–25 season include debuts at the Lucerne and Moritzburg festivals, a return to the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, and two chamber music recitals at Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie. He also returns to the Bournemouth Symphony and Nordwestdeutsche Philhamonie. Recent concerto highlights included a UK tour with the Sinfonia of London and a European tour with the LGT Young Soloists, which included performances at the Berlin Konzerthaus and Vienna Musikverein. Past seasons have seen Bartlett in recital at Wigmore Hall and Paris’s Salle Cortot.

An exclusive recording artist with Warner Classics, Bartlett has released three widely acclaimed albums on the label. La Danse (2024) focuses on solo works by Couperin, Debussy, Hahn, Rameau, and Ravel, and received five-star reviews in The Times, as well as Editor’s Choice in Gramophone. Rhapsody (2022), recorded with the London Philharmonic, featured concertos by Rachmaninoff and Gershwin. The recording was released to critical acclaim, also receiving Gramophone’s Editor’s Choice accolade and a five-star review in BBC Music Magazine.

Bartlett was named the BBC Young Musician of the Year in 2014, leading to engagements with the BBC Symphony, BBC Scottish Symphony, Bournemouth Symphony, and Ulster Orchestra. In 2015, he made his BBC Proms debut performing Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. And in 2019, Bartlett was awarded first place at the Young Concert Artists International Auditions in New York.

Learn more about Martin James Bartlett in our April feature.