In This Program

- Welcome

- Feature: Undaunted Enthusiasm

- Feature: Mozart as Mirror

- Community Connections: Acción Latina

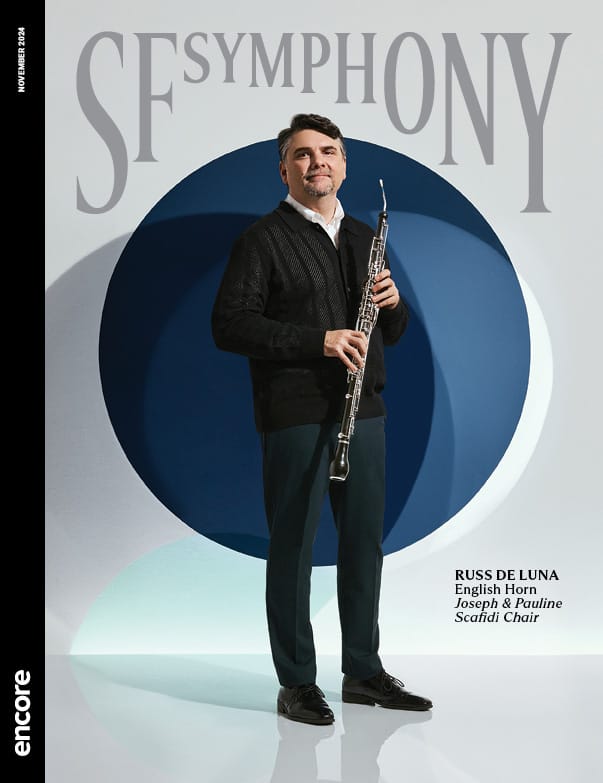

- Meet the Musicians: Russ de Luna

- Print Edition

Welcome

One of the defining characteristics of an orchestra is its ability to take many different shapes and forms. Whether it’s a duo performing a chamber concert at one of San Francisco’s public libraries or the full orchestra unleashing its power in a Mahler symphony at Davies Symphony Hall, the Symphony is an ensemble whose versatility shines both individually and as a group.

Our chamber music series offers a wonderful opportunity to get to know the musicians of our orchestra in an intimate setting. On November 10, you’ll hear our musicians—including several of our newest members—spotlighted in a wide-ranging chamber music concert at Davies Symphony Hall, featuring Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro and chamber arrangements of works by Bach, Strauss, and Mozart.

Chamber music is also at the heart of two of our most important community programs: Music in the Wards offers monthly performances to inspire patients, families, doctors, nurses, and staff of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, while the Community Chamber Concert series brings small ensembles of Symphony musicians to communities across the Bay Area. This month you can catch Symphony musicians in performance at the Ocean View branch of San Francisco Public Library on November 16. To find out when Symphony musicians are coming to your neighborhood, visit sfsymphony.org/communitychamber.

The versatility of our players shines through in their work mentoring young musicians. Nearly 20 members of the Symphony coach the developing musicians of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra each week, offering an unparalleled opportunity for these young players to learn the orchestral repertoire from the foremost musicians in the field. This year, we are pleased to welcome conductor Radu Paponiu as the new Wattis Foundation Music Director of the Youth Orchestra. You can hear Radu and the YO in their debut concert together on November 24, in a program featuring YO Concerto Competition winner Harry Jo as saxophone soloist in Takashi Yoshimatsu’s Cyber Bird Concerto.

Whether shining in orchestral concerts at Davies Symphony Hall, performing in intimate spaces, or guiding young talent, the artistry and commitment of our musicians shines through in everything they do. We invite you to join us for these upcoming events and experience the Symphony’s impact both on stage and throughout the community.

Undaunted Enthusiasm

Conductors Nicholas Collon and Kazuki Yamada debut with the SF Symphony | By Steve Holt

WHEN NICHOLAS COLLON isn’t guest conducting, he has two homebases: He’s chief conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony in Helsinki and founder and principal conductor of the Aurora Orchestra in London, his hometown. That ensemble is renowned for playing masterpieces such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony without a score, an almost unheard-of feat in classical music.

“We do something like that two or three times a year,” Collon says. “It’s some extra stress for the players. They spend a lot of time learning the music, but that’s the joy of it, going so deeply into that incredible music.

“It also opens the door for other possibilities in how you present the music. For example, in the first half of the Beethoven Ninth concert, we did a big, 45-minute long, almost a play. It was me and two actors exploring Beethoven at the time he composed it, and his deafness, all the context of him writing the symphony.

“In 10 years we’ve probably done about 100 performances from memory, and there’ve never been any big mistakes. I’ve had many more mistakes from orchestras playing with music than without!”

What should the audience know about his conducting? “I guess I’m somewhat defined by the work I do. I cover a huge range of repertoire: I’ve done lots of contemporary music, but I do Baroque music, lots of traditional, Romantic repertoire. I think I’m curious—that’s probably the best way of putting it—curious about what music can do, and very passionate, really, about what music can bring to people and the power that it has.”

For Collon’s debut with the San Francisco Symphony, November 7–9, there will be scores on the music stands. He’s leading off with a suite from Powder Her Face, an opera by Thomas Adès. “It’s quite an amazing story, based on a famous, scandalous affair,” which involved the Duchess of Argyll, whose divorce proceedings appalled and titillated the British in the 1960s. “Adès is one of the great contemporary composers for me, and he knows exactly how to write brilliant music for orchestra. This suite makes a really good concert opener, to show off what an orchestra can do.”

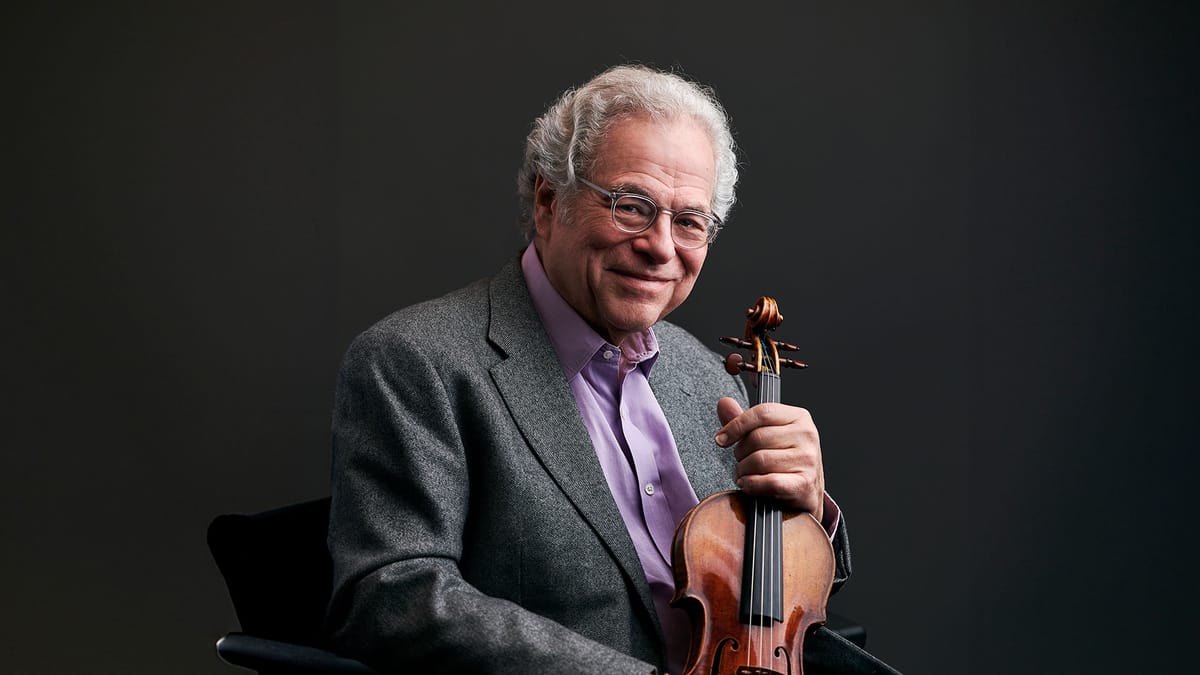

Next on the bill: Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, featuring soloist Conrad Tao, an award-winning pianist and composer who has been heard at Davies Symphony Hall several times in recent seasons. “He performed with my orchestra in Helsinki, and they really liked him,” Collon says. “He’s very well-respected, and of course the Tchaikovsky is a fantastic piece of music.”

The Enigma Variations have delighted and puzzled classical music lovers for over a century. Elgar described the piece as a series of portraits of some of his closest musical friends. “It is such an enigma that people have tried to work out: what is the secret code behind the principal theme?” Collon notes. “Is there a love interest? Is it something else? Every year or so, I see another article in the newspaper claiming to have discovered what the enigma is. But musically, it’s a wonderful set of variations that just explores every kind of color of being human, through music. It’s beautifully put together, and it’s great fun to play as well.

Collon’s history with the piece stretches back to a youth orchestra performance he played when he was 11. “I very clearly remember just being totally bowled over by the music. And then, probably 10 years later, I conducted it for the first time, and I’ve been conducting it ever since. I’m very much looking forward to conducting it, and the rest of the program, in San Francisco. I’ve never been to the city, and I know from Esa-Pekka Salonen what a great orchestra it is.”

Collon takes an organic approach to rehearsing with an orchestra for the first time. “First, I like to see what they bring for me to hear. That’s always an interesting moment. Then you have to be quite laser focused. What do they need? What can I bring? How can I be efficient? But I also ask how I can bring this music to life in my own way. And of course, these three pieces we’ll be doing have different challenges. The Adès piece has quite a lot of difficult changes in time, meter, and rhythm. Sometimes it depends if the orchestra knows a piece or not, and whether they’ve played it recently.”

When asked if he has time for sightseeing in his busy schedule, Collon laughs. “I wish I did. The problem with guest conducting is, you’re always learning new music. If you’re not rehearsing or performing, you’re back in the hotel, studying scores. But I do get to go to amazing places. I’ll try to immerse myself in San Francisco. And of course, it’s such a great pleasure to bring this brilliant music to an audience.”

KAZUKI YAMADA IS DELIGHTED to be making his conducting debut with the San Francisco Symphony, November 15–17. “It’s such a great orchestra,” he notes. “When I got the invitation, I just thought ‘Wow, really, wow!’ To be with this group that’s been led by people like Seiji Ozawa, Michael Tilson Thomas, and so many others, I’m very honored.”

Born in Kanagawa, Japan, Yamada initially studied at the Tokyo University of the Arts, later working closely with Ozawa to refine his conducting skills. He is currently the music director of the Monte-Carlo Philharmonic and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; he also keeps up a busy schedule of guest conducting appearances. He has spent the past decade or so conducting mostly in Europe, but lately has been invited to lead several prominent US orchestras, including those of Boston, New York, Chicago, and Cleveland.

His San Francisco program begins with the United States premiere of Dai Fujikura’s Entwine. “Dai is a very close friend of mine, and I’ve conducted his other works many times,” Yamada says. “All of his pieces have a special sound, being rhythmic, enthusiastic, and totally beautiful. His pieces are challenging for the musicians, but afterwards, everybody can be smiling: the musicians, the audience, and the conductor.”

As for playing with Hélène Grimaud, soloist in Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major, Yamada says, “I’ve wanted to perform with her for such a long time, and now it’s finally happened. The Ravel is a very colorful piece and an iconic part for the pianist of course, but it also puts orchestra members in the spotlight. Many of the musicians have solos: the piccolo, the English horn, the trumpet. It’s a little difficult technically, but it’s a balanced piece. There’s even a jazz feel to it.”

The concert closes with Fauré’s Requiem, featuring soprano Liv Redpath, baritone Michael Sumuel, and the San Francisco Symphony Chorus, under the direction of Jenny Wong. “This is music anchored in the Christian religion. I’m a Buddhist, but I feel something special in it: It’s very open and welcoming to everyone. It’s scored for a small orchestra, but every note has deep meaning. I’m also very much looking forward to working with the SF Symphony Chorus for the first time as choral conducting is very important to me. I love the human voice, and I want to do something special with them.”

Like all guest conductors, Yamada must be very efficient with his rehearsal time. “First, I like to respect the way the players make music. Of course, I can watch videos and listen to CDs but I can’t really get a sense of the orchestra’s atmosphere until I’m on the rehearsal stage with them. I want to feel their atmosphere and share it with them. After that, I’ll make suggestions and try out different approaches. Sometimes the reaction is great; sometimes not, so I make adjustments.”

Like Nicholas Collon, Yamada wishes he had more time to enjoy the cities on his globe-trotting itinerary. “Sometimes, unfortunately, I have a very tight schedule for rehearsals and performances, so there’s no time for sightseeing. However, I recently conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood, and my family and I had three or four days to discover Boston, which was very nice.”

Assuming he can make the time, what’s on the agenda for his first visit to San Francisco?

“I want to see and ride the cable cars. Is it true that sometimes the people have to get out and push? I want to walk around the city but I hear it’s not so flat!”

Mozart as Mirror

The Making of a Reputation | Adapted from an essay by Thomas May

Consider a persistently popular (although misleading) image surrounding the story of Mozart’s death. On a miserably cold, rainy day, the great composer (so the story goes) is unceremoniously tossed into an unmarked “pauper’s grave”—the final indignity heaped on a creative spirit whose true worth it will be left for posterity to fathom. As with so many assumptions about Mozart, the actual events have become almost inextricably entangled with a profusion of myths from the past two centuries (and counting).

Take that trope of the neglected genius. There’s no question that some of what we’ve since come to revere as most valuable about Mozart failed to gain appreciation in his lifetime. Yet his contemporaries (both fellow professionals and ordinary music lovers) cherished Mozart and his artistry right up to the untimely end of his career—not just the sensational memories of his bygone youth as a prodigy. Nor (pace Pushkin—the first to dramatize the baseless rumor that Salieri had poisoned Mozart) did it require a jealous disposition to understand the composer’s uniqueness. Indeed, within a month of Mozart’s burial, one of the Viennese papers suggested an epitaph for that now-notorious grave: “As a child, he who lies here, through his harmonies, added to the wonders of the world; as a man, he surpassed Orpheus. Go your way and pray earnestly for his soul.”

Yet Mozart’s reputation not only spread rapidly (foregoing the pattern of a lengthy period of neglect followed by “revival”). From the start, it also fragmented into sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory myths that began to compete with each other: Mozart as the flawless, angelic vessel of timeless beauty; the visionary who expressed “demonic” passions; the innocent or even idiot savant with no idea what he was about; and—most enduring of all—what biographer Maynard Solomon has characterized as “the eternal child,” a myth in itself replete with all manner of contradictions (from the golem-like child prodigy to the scatological and polymorphous bon vivant glorified in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus).

One constant, however, amid all the competing narratives, is that each of these myths tends to focus on a particular aspect of Mozart’s output—whether drawing attention to a few specific works or to certain traits that appear across genres. Mozart’s reputation is thus continually re-assessed and redefined, its ever-changing images serving as a mirror to the preoccupations of his admirers.

This is the case, to be sure, with all great artists. But the situation with the Mozart myth(s) becomes especially intriguing when we take into account some of the reasons behind the shifts in how the composer is appraised.

An important key is the revolution in how music history itself came to be conceived as the 19th century advanced. The change from previous patterns was as profound a rupture in its own way as the French Revolution punctuating the end of Mozart’s life. Richard Taruskin (in his Oxford History of Western Music) points out that Mozart died just as new social and economic forces were beginning to shape the need for a musical repertory or canon.

Mozart’s reputation thus becomes bound up in a tension between two conflicting impulses. One is toward a sharpened awareness of his position as an artist bound by the conventions of his time; the other fixates on Mozart as transcending time, not only prophesying the future in bold ways but becoming “timeless.”

But while Mozart became enshrined in the canon as a musical “absolute,” there developed a paradoxical tendency to relativize his legacy in light of the newly emerging model of musical progress. The Romantic generation saw him as a figure bounded on one side by Bach’s complexity and on the other by the towering might of Beethoven. What got lost in this view is Mozart’s profound incorporation of Baroque contrapuntal texture, as well as Beethoven’s own anxiety of influence vis-à-vis such works as the Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor—one of the handful of Mozart’s instrumental compositions on which the 19th century became fixated.

A curious twist occurred as the premium on originality increased during the first decades of the 19th century. In some quarters at least, recognition veered away from Mozart’s astonishing originality in, for example, establishing the template for the Romantic concerto. Music scholar John Daverio acutely observes the contradiction that developed as Mozart’s time receded into the distance, while his music assumed a more comfortable presence: “With increased understanding…comes loss—of the sense for precisely those idiosyncrasies that made Mozart’s music such a challenge for early audiences.”

With the composer’s “strangeness” smoothed over, an especially persuasive myth developed, inspired by contemporary concepts of classical art from ancient Greece. This is the Mozart of Apollonian order and beauty. This Mozart of classical grace represents one of the strategies for reclaiming him as “timeless.” It is also, unfortunately, easily degraded into the later insipidly piped-in wallpaper Mozart, an aural valium to induce tranquility.

Mozart’s significance for the new century became firmly established. But there was a tradeoff: Only a select few works enjoyed this high level of adulation, as if the majority of the composer’s output (especially the earlier instrumental music) were essentially superfluous—too reminiscent of the era of periwigs and snuff boxes in which Mozart was chronologically bound (as it was perceived).

E.T.A. Hoffmann—a synthetic artist (fiction writer, critic, and composer all in one) who even changed his name in homage to his idol (the A standing for “Amadeus”)—offered another strategy for “rescuing” Mozart from his time: recasting him as a Romantic. In this way, Mozart was seen to foreshadow the path toward the full blossoming of instrumental music attained by Beethoven. Consider Hoffmann on the Symphony No. 39: “Mozart leads us into the realm of spirits, but, without pain; it is more of an anticipation of the infinite. Love and melancholy sound in lovely spirit voices; night arrives in a purple glow, and with unspeakable longing, we move towards them who wave at us to join their ranks and to fly with them through the clouds in their eternal dance of the spheres.”

Hoffmann’s evocative language hints at a basic ambivalence in approaching Mozart. It foreshadows the conflict to come later in the century between program music and “absolute” music. This comes to the fore in Wagner, who sees Mozart as all-too-trapped in his era, writing “music which, between attractive melodies, also offers an attractive hubbub for conversation’s sake…[so that] the perpetually recurring and noisily garrulous half-closes of the Mozartian Symphony make the impression as if I were hearing the clatter of a prince’s plates and dishes set to music.”

From the start, Mozart’s reputation fragmented into sometimes complementary, sometimes contradictory myths that began to compete with each other.

The highly influential critic Eduard Hanslick championed Mozart as the quintessence of absolute music. But even Hanslick complained about the composer’s “foursquareness.” In other words: Accompanying the dominant myth of Mozart as a time-transcending genius (whether by those inclined to the Apollonian view or by the expressive proto-Romantic camp) came a dissonant undertow of frustration with what were seen as the restrictions of his age. That frustration became projected onto Mozart himself in the film Amadeus as the composer protests stuffy bores who “sound as if they sh-t marble.”

At the far extreme from this reluctance to listen to Mozart sympathetically is the worship one finds among those who idealize the composer. The autograph score of Don Giovanni was treated as a sacred relic, while Tchaikovsky described his admiration in overtly religious terms. Mahler directed a pivotal series of productions that refurbished the vitality of Mozart’s operas. He declared that the contemporary symphonic composer should strive for “the polyphony of Bach combined with melody of Mozart.”

Yet it is Tchaikovsky who also opened the door to a rich new way of appraising Mozart. The extraordinary stylistic range of his opera The Queen of Spades includes an elaborate Mozartian pastorale that anticipates the neoclassical aesthetic. Instead of being “rescued” from his own time, Mozart becomes incorporated in a fresh approach to creativity. Richard Strauss, another ardent Mozartian, does something similar in the synthesis of his late Romantic ripeness with the operatic humanity of Mozart in his Hoffmansthal collaborations.

Even if we’ve been liberated from the illusion of musical progress, it’s difficult to avoid the fallacy that we can understand Mozart better in hindsight than could past music lovers: We are, after all, as susceptible to the myth-making. The truly wonderful thing is how Mozart’s music can contain all this plenitude and all these contradictions. It’s not a coincidence that the most haunting likeness of Mozart—this “remarkably small man, very thin and pale, with a profusion of fine fair hair, of which he was rather vain,” as the tenor Michael Kelly recalled him—is the unfinished painting by Joseph Lange: as if it is left to us to complete the image in our imaginations. As Anthony Burgess has put it so beautifully, Mozart “reminds us of human possibilities. He presents the whole compass of life and intimates that noble visions exist only because they can be realized.”

Wearing his hat as music critic, George Bernard Shaw observed a danger that confronts audiences today as much as it did in his time: Mozart’s very omnipresence can lull us into ignoring just what is so great about his music. In his coverage of the 1891 concerts marking the centenary of the composer’s death, Shaw notes how difficult it is to hear good Mozart. The strategy to avoid rote performances that take him for granted is to approach Mozart in a way that allows the music simply to speak for itself: “[When we] have become conscious that there are grades of quality in emotion as well as variations of intensity, then we shall be on our way to become true Mozart connoisseurs.”

Photo: Unfinished portrait of Mozart by Joseph Lange, 1782–83

Community Connections

Acción Latina

Acción Latina promotes cultural arts, community media, and civic engagement as a way of building healthy and empowered Latino communities.

Acción Latina’s cornerstone media project, El Tecolote, founded in 1970, has served San Francisco for more than five decades. With a circulation of 7,000, El Tecolote is the longest running bilingual (English/Spanish) newspaper in California. The digital reach of the publication has expanded via its daily website, social media, and weekly newsletter.

Acción Latina is also home to the Juan R. Fuentes Art Gallery, which features emerging and established Latinx artists. It has produced the annual Encuentro del Canto Popular social justice concert for more than four decades. Along with a dozen cultural organizations and small businesses, Acción Latina produces the Paseo Artístico series, a recurring community art stroll that brings free arts programming and multidisciplinary performances to the Calle 24 Latino Cultural District in San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood.

Through its community-based media and arts programming, Acción Latina strives toward its vision of a community where art and culture are robust, quality bilingual news is accessible, civic engagement and participation thrives, and where local Latinx history is documented and celebrated.

To learn more about Acción Latina’s programming, visit accionlatina.org and check out eltecolote.org for the latest news.

Meet the Musicians

Russ de Luna, English Horn • Joseph & Pauline Scafidi Chair

Russ de Luna joined the San Francisco Symphony as English Horn in 2007. He has appeared as a soloist with the orchestra in the US premiere of Outi Tarkiainen’s Milky Ways, as well as in Copland’s Quiet City and Sibelius’s The Swan of Tuonela. He has also performed with the orchestras of Atlanta, St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, and New York, and the Saito Kinen Orchestra in Japan.

How did you begin playing oboe and English horn?

It all started in sixth grade for me, playing saxophone and then piano. Around eighth grade my band director suggested I could probably get a good scholarship if I switched to oboe. I didn’t know what that was, so they gave me an oboe and a fingering chart and I fell in love with the instrument.

Did you have some important teachers after that?

I studied at Northwestern University with Ray Still, who was the principal of the Chicago Symphony for 40 years. And after that I studied with John Dlouhy, who was the principal of the Atlanta Symphony. And finally I went to Boston University, where I studied with Ralph Gomberg, who had been principal of the Boston Symphony.

Do you remember your first concert with the SF Symphony?

I won the job in 2006 on Halloween day, but couldn’t start until August 2007, so my first week as a member of the orchestra was a tour to Europe with MTT. We played Mahler 7.

What are some of your favorite English horn solos… besides Dvořak’s New World Symphony?

Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde has a huge off-stage solo, which I got to play with the Cleveland Orchestra a few years ago. And Rodrigo’s guitar concerto has a middle movement with a beautiful English horn solo, which we played here last summer. One piece that I’ve never done is Berlioz’s Rob Roy Overture, which has a duet for English horn and harp. I don’t know why it doesn’t get played in concert, but it’s on every English horn audition.

Can you tell us a bit about your specific instruments?

I play Lorée instruments made in Paris, and the English horn I’m playing on right now is unique. It actually belonged to the father of one of our Symphony violists, Christina King. Her father was an amateur oboist and was giving away his instruments as he was getting older. She asked me to take a look, and I said I’d love to see them. It turns out it was the best English horn I’d ever played.

Do you have a concert day routine?

It depends on what I’m playing. If I have something exposed and soloistic, I do a lot of reed work. There’s a lot of making reeds when you play oboe and English horn. So I make sure all my reeds are in good shape and then I usually take a nap before a concert.

What are your other musical activities outside the Symphony?

I’m on faculty at San Francisco Conservatory and love teaching. I lead a week of oboe camp in Birmingham, Alabama, each summer, and I teach masterclasses around the country. I also play at Sun Valley Music Festival.

And what do you enjoy doing besides music?

I love lifting weights so I go to the gym quite a lot. I also like going to Warriors games and watching the 49ers.

What are you looking forward to this month at the Symphony?

The Ravel Piano Concerto (November 15–17). That’s a beautiful piece with one of my favorite English horn solos in the slow movement.

Print Edition