In This Program

- Welcome

- Feature: “Wrestling the Dream Down”

- In Celebration: Retiring SF Symphony Musicians

- Feature: Rhapsody in Blue at 100

- Community Connections: OMI Cultural Participation Project

- Meet the Musicians: Rainer Eudeikis

- Print Edition

Welcome

When we put together a San Francisco Symphony season, we consider not only the amazing artists and repertoire that will grace our stage but also the entire concert experience and how we can best connect with our audiences. We are constantly exploring new ways to reimagine this experience, and it’s your enthusiasm and curiosity that inspire us to push boundaries and think outside the box. Many of you have shared how much you enjoy learning more about the music we perform, as well as exploring other concert activations that deepen your connection to the art.

This month, we are bringing the beauty of nature into Davies Symphony Hall with a photo exhibit in conjunction with Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Orchestra’s performances of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and Debussy’s La Mer, October 18–20. Created by talented young photographers from San Francisco nonprofit First Exposures, these images offer a unique and beautiful perspective on the natural world. They are the perfect visual companions to our performances of Beethoven’s and Debussy’s works, which paint unforgettable pictures of nature through music.

In addition, we are proud to highlight the work of local artists through a special lobby installation in connection with our upcoming annual Día de los Muertos celebration on November 2. These artworks not only help us to remember family and friends but also connect us to the rich cultural tapestry of this vibrant tradition.

By inviting these local artists to share their work in our hall, we are not just adding to the concert experience—we are building a creative community.

We are eager to share these experiences with you and look forward to hearing what you think as we continue to find new ways to bring music and art to life.

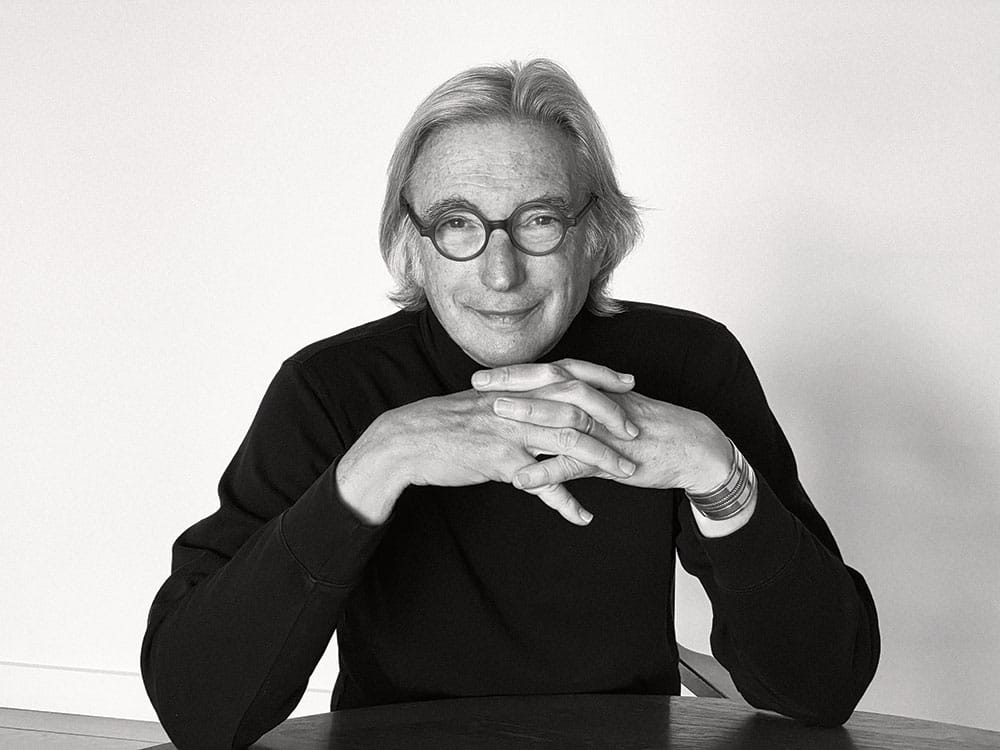

Matthew Spivey

Chief Executive Officer, San Francisco Symphony

“Wrestling the Dream Down”

Reflections on the composer-conductor bond By Thomas May

Just a year after Gustav Mahler took over the reins at the Vienna Opera in 1897, his contemporary Arturo Toscanini (seven years younger) arrived at the helm of La Scala. Toscanini would in time become the prototype of the conductor as culture hero, known around the world simply as “Maestro.” This is the model still dominating the classical music scene. And it encapsulates a shift in emphasis toward the performer. Mahler’s dual role as composer and conductor is highly emblematic. He stands at the crossroads, representing a holistic approach that is considered rare in our era of increased specialization.

Yet, rare as it has become, the Doppelgänger identity of composer and conductor does persist. Michael Tilson Thomas, John Adams, and Esa-Pekka Salonen are three leading figures in classical music today whose identities embrace the roles of both composer and conductor. Their insights give us a contemporary perspective on music making as a process of continually unfolding revelation.

Of course, Mahler exemplifies a long-standing tradition of musical multi-tasking that was integral to Western classical music’s development. Well before the arrival of the specialist conductor, it fell to the Kapellmeister, or musical director, not only to coordinate performances but to provide a steady supply of fresh music. J.S. Bach’s duties at Leipzig’s Thomaskirche made him the equivalent of a one-man music factory as he composed new cantatas for weekly liturgies, prepared the choir and instrumentalists, all the while maintaining a high profile as one of Europe’s master organists. When Haydn was hired as musical master of ceremonies for Prince Esterhazy’s estate, the job meant writing fresh music as well as performing it.

The progressive division of labor and specialization that followed have proved relentless. But, as Esa-Pekka Salonen observed, it’s “not just a musical phenomenon. It’s happening in every field, from manufacturing to medicine.” Referring to computer networks, he said, “most systems are becoming so complex that even the most intelligent individual can only grasp a fraction of a system’s totality.”

Michael Tilson Thomas has described a mirror-like process that binds the composer and the conductor. From his perspective, to compose begins with the impulse to express a personal take “on a certain experience or quality of living. The musical gestures that result define a sort of dreamscape.” But however spontaneous that initial impulse, an effort of will is required to give it shape. Composing “isn’t only about having the dream,” MTT continued. “It’s about wrestling the dream down into a form so others can know it. Wrestling it down means being willing to go through a difficult process—while keeping the music still a dream. Sometimes the wrestling is to envision the musical idea for a particular person or performer.”

Conducting, said MTT, involves the reverse process: working back from the notes in a score to the dream that those notes attempt to wrestle down. The conductor who also composes has an advantage in being more closely attuned to this process. “That’s what Mahler as a performer was trying to do,” MTT continued. “The score is really a kind of codebook. Making the music itself come alive is a kind of sacred thing for me. You look at these little dots and dashes Mahler put on the paper, you begin to play them, and it’s as if the spirit comes off the page and envelops us and somehow draws us together as one spirit.”

When it comes to interpreting his own music, John Adams said that “after conducting a piece many times, as for example I have done with my Violin Concerto or with Harmonielehre or Nixon in China, I actually refine my views on the music. Frequently I’ll go back to the original score and minutely alter things like dynamics and tempi.” This echoes the pattern we find in Mahler. To take just one fascinating example of his constant tweaking of scores, his request for a five-minute pause following the cataclysm of the Second Symphony’s opening movement was a bold and unprecedented strategy. After numerous times conducting the work, however, Mahler felt confident to leave the instruction in place.

But Adams observed that experience as a composer can sharpen the intuitive understanding a conductor brings to another composer’s work: “There are things that composers do that are similar to the craft of painting. For example, how you prepare a background, or how you accomplish shading or chiaroscuro, or how you produce an effect of a vanishing point. All of these are matters of technical skill coupled with inspired imagination. What draws me to a composer like Sibelius, for example, is the way he produces these effects. I know what he’s going for because I have struggled with the same issue. So in rehearsing the piece, I focus on bringing out what I believe he was attempting.”

Clearly, we lose a certain interpretive richness in the separation of identities into composer versus conductor. This division of labor results from a complicated mix of factors. Much of the division has happened for purely practical reasons. Salonen, for example, recalled that “I never had any plan for an international conducting career,” hoping instead to devote himself wholeheartedly to composition. But when he was called on to conduct a Mahler symphony (ironically enough) on short notice in the 1980s, his conducting career was launched. “It took me completely by surprise.”

Without the slightest hint of nostalgia for the past, Salonen pointed out that “the volume of classical music is vastly bigger than it was 50 years ago. The number of musical events per second has increased, so there’s more demand than ever for conductors. Pierre Boulez once said that if someone shows any talent for conducting, they’ll be immediately sucked into the international machinery for conducting.”

Still another possible pressure that split composers and conductors is a central tenet of modernist aesthetics: the need to be original. Thus, a certain anxiety may have discouraged composers from the podium. Assuming they would be accused of having been influenced by the past, they may have avoided the constant rapprochement with standard repertory that is essential to a conductor’s role. “The idea of total and utter originality—that every new piece has to be a tabula rasa—is a recent one, a postulate of postwar modernism,” Salonen explained. “I don’t think the human mind works like that. Creativity is about reacting: As in a chemical process, new substances are born. The old and honorable way is the one composers have been following for centuries. If there’s something you like, lift it and modify it to your purposes. The most creative people create new substances that are very unexpected.”

Both Michael Tilson Thomas and Esa-Pekka Salonen have noted their formative experiences with avant-garde trends as young musicians and how this impacted their identities as composers. In his 1994 book Viva Voce, MTT described how his involvement with improvising and performing experimental music eclipsed his desire to compose: “The sort of music that I really want to write,” he felt early on, wasn’t “like anything I [was] playing.” He concluded that “the music I want[ed] to write [was] more like my father’s music. It’s melodies, it’s songs, it’s theater music.” In 1989, MTT reached a turning point by composing his From the Diary of Anne Frank: “It was an opportunity for me to return to writing the sort of music that I might have done just at the point where I left off composition.” The result was “to cause me to take my writing seriously, to care about it, and to care about wanting to have people hear what was going on inside my head.”

In his composing, MTT has found that his work as an interpreter leads to insights about communicating with his audience through his own music. Salonen, on the other hand, recognized that being unexpectedly thrust into the limelight as a conductor allowed him to evade the artistic crisis he needed to face as a composer. “Instead of suffering the crisis as a composer, I suffered it as a conductor.” But the heart of the crisis echoes what Michael Tilson Thomas also experienced. Wheareas MTT did not want to write the kind of European avant-garde music he was conducting, Salonen “realized that the music I was composing [as a young avant-gardist] and the music I loved to perform didn’t sound the same.” After a decade or so of losing himself on the podium, he had an epiphany that opened up his inspiration to compose seriously again: “It wasn’t a conscious decision. I woke up one morning and felt I was free from the rules of my training as a composer. I realized that the [tenets of the postwar European avant-garde] were not my truth. One of nice things about getting older is that one tends to become a little more liberal in aesthetic judgment; one knows there is more than one truth.” The breakthrough that followed was Salonen’s acclaimed large-scale work for orchestra, L.A. Variations.

The composer-conductor bond can also have its natural rhythm. “Composing is obviously a very personal, introverted activity,” Adams offered. “I tend to become extremely habitual in my daily life when I am home writing and can probably seem rather ungregarious and hermetic to my neighbors. Conducting is completely the opposite: it’s very ‘other-oriented,’ very much about dealing with other people’s personalities and emotions, and it involves quick, strategic decisions. If I didn’t have the continual experience of performing, I strongly suspect that my creative life would atrophy in some way. But the two activities, taken together, form a wholeness that feeds my imagination. For me, the hardest thing is the transition—having to go from the solitude of my studio to the busy, frenetic activity of preparing and performing a week of concerts with a large symphony orchestra. But once I’ve made the adjustment, I find I’m equally happy to be reunited with my other, more sociable self.”

“Creativity is about reacting,” said Esa-Pekka Salonen. “As in a chemical process, new substances are born.”

In the early 20th century, as many of the trends reflected here were just beginning to run their course, the phenomenal musical personality Ferruccio Busoni published a visionary manifesto called Outline for a New Aesthetic of Music. Busoni’s concept of musical truth combines a kind of Platonic idealism with a pluralistic breadth very much in keeping with today’s musical pulse. “The performance of a work is also a transcription,” declared Busoni. “Whatever liberties it may take, it can never annihilate the original.” Indeed, his description of the act of capturing musical thoughts and preserving them in a score shares a fascinating resemblance to Michael Tilson Thomas’s image of “wrestling the dream down.” Said Busoni: “Every notation is, in itself, the transcription of an abstract idea.” Busoni warned against puritans who treat the score as “a rigidity of signs.” The creative act is fluid and requires a transaction between composer and performer: “What the composer’s inspiration necessarily loses through notation, his interpreter should restore by his own.” If the composer-conductor bond has reinforced one truth, it is this: that, for the dream ultimately to be wrestled down, the audience too must become part of the collaboration. A conductor helps translate the composer’s codebook. Those who listen complete the translation.

The compositions of Michael Tilson Thomas are featured in a new four-CD box set from Pentatone, released October 4. This special release includes several San Francisco Symphony recordings, both previously released and archival. All proceeds will be donated to brain cancer research at UCSF Brain Tumor Center.

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts the first SF Symphony performances of his Cello Concerto, with Principal Cello Rainer Eudeikis in his Symphony solo debut, October 18–20.

John Adams’s new piano concerto, After the Fall—a San Francisco Symphony commission—receives its world premiere by its dedicatee, pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, in concerts conducted by David Robertson, January 16, 18–19. Ólafsson performed Adams’s previous piano concerto, Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?, on SF Symphony subscription concerts in June 2022.

Esa-Pekka Salonen closes the 2024–25 season with performances of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, June 12–14.

Rhapsody in Blue at 100

A San Francisco HistoryBy Steven Ziegler

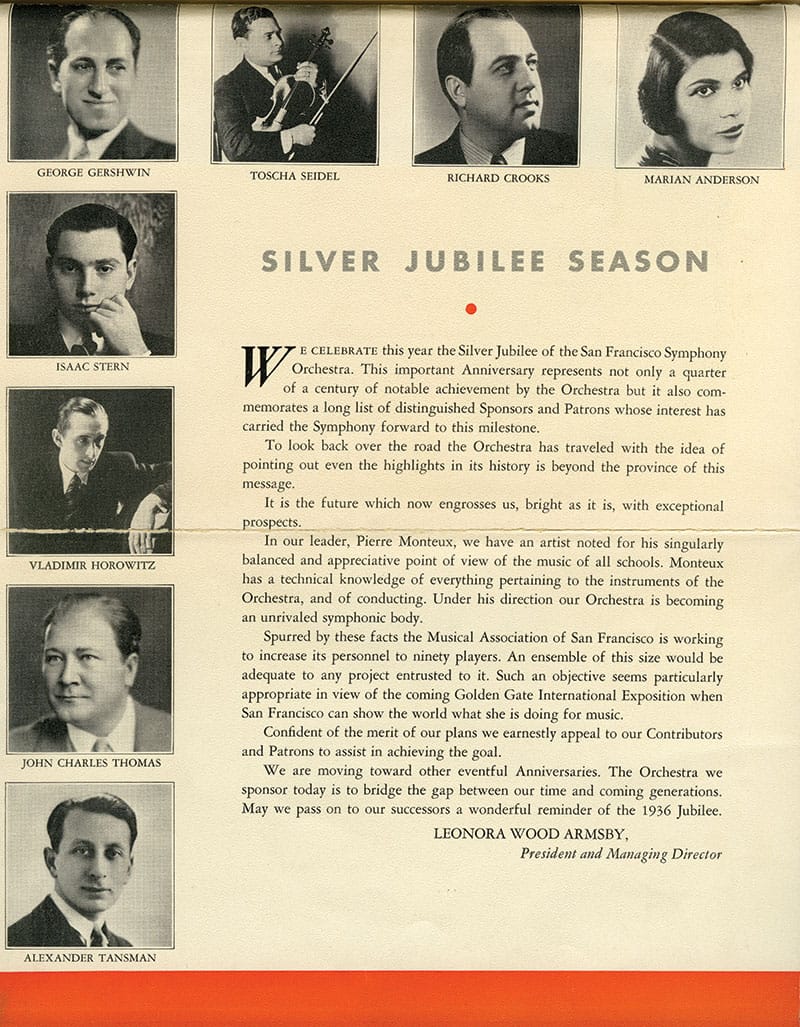

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue is a piece that never seems to be far from our minds, but the work’s centenary in 2024 has sparked new discoveries and important conversations about its relevance in today’s world. Pianist and composer Ethan Iverson recently wrote a probing essay about it for the New York Times, while pianist Lara Downes released a new recording in which composer Edmar Colón reimagines Gershwin’s work to reflect on a century of immigration and transformation. This month’s San Francisco Symphony program conducted by Thomas Wilkins, with pianist Michelle Cann, places Rhapsody within the context of other 20th-century American works by Gershwin, Leonard Bernstein, and William Grant Still.

Following its successful 1924 premiere as part of conductor and impresario Paul Whiteman’s “Experiment in Music” concert at New York’s Aeolian Hall—Gershwin was piano soloist—Rhapsody in Blue made its way to the San Francisco Symphony in 1931. (Fun fact: Whiteman spent some time as a string player in the San Francisco Symphony in the 1910s before launching his career as a bandleader.)

Symphony violinist David Schneider recalled a 1930s performance at the War Memorial Opera House in his memoir of the San Francisco Symphony, Music, Maestros, and Musicians:

It was a Friday afternoon concert when all the society ladies wore white gloves, and the retired gentlemen, in their grey-striped trousers, spats, and morning coats, were sitting and enjoying the culture that a symphony orchestra offered them. Suddenly there was an invasion from another world. From that first dirty glissando of the clarinet, there was the feeling that their raw emotions were being assailed. In the staid atmosphere of the Opera House, the rough syncopated rhythms and the raucous dissonant harmonies shocked the patrons out of their seats.

Gershwin himself played Rhapsody in Blue with the San Francisco Symphony in a January 1937 program that featured him as conductor and pianist in several of his works. Schneider observed:

[Gershwin] was generally at ease with professional musicians, and his folklike music came out exactly that way when he conducted. [Pierre] Monteux conducted his Piano Concerto in F, and Gershwin was really a natural pianist. He played the piece as if he were in his own living room, and Monteux followed him perfectly. It was the ideal blending of all the elements that make up music, and I was thrilled by it.

Unfortunately, we’ll never know what further Gershwin–San Francisco Symphony collaborations might have brought, as he passed away at the age of 38 in July 1937, just a few months after his Symphony debut.

Rhapsody in Blue has remained a staple on San Francisco Symphony programs over the years, performed by a fascinating mix of pianists from both the classical and popular music worlds: André Previn, André Watts, Oscar Levant, José Iturbi, Michael Feinstein, Marcus Roberts, Marc-André Hamelin, Yuja Wang, Makoto Ozone, and most recently Aaron Diehl. (Special mention goes to harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler, who performed his version of Rhapsody in Blue with the Symphony on two separate occasions). A few brave conductor/pianists have also taken on the work here: Jeffrey Kahane, John Covelli, Peter Nero, and Michael Tilson Thomas.

As Rhapsody in Blue enters its second century, it’s clear that the piece isn’t going anywhere. Beyond continuing to delight audiences, we can hope that Gershwin’s work will also inspire the next generation of composers eager to build upon his dream of a “musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness.”

In Celebration

Chunming Mo, Pamela Smith

We bid farewell to two musicians retiring from the San Francisco Symphony.

Violinist Chunming Mo joined the Symphony in 1991, under Herbert Blomstedt. Born in Shanghai, China, she started to play the violin at age 11. She went on to earn her bachelor’s degree from the Shanghai Conservatory and later earned her master’s degree from the San Francisco Conservatory. Before becoming a member of the San Francisco Symphony, she was a member of the Shanghai Symphony and the Sacramento Symphony. She retires from the Orchestra this month.

Oboist Pamela Smith retired from the Symphony at the close of the 2023–24 season. She studied at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Belgium and with former San Francisco Symphony principal oboe Marc Lifschey at the San Francisco Conservatory. Upon graduation, she joined the newly formed San Francisco Ballet Orchestra. She first played with the San Francisco Symphony in 1980 alongside her mentor, Lifschey, and became a permanent member in 1988, holding the Dr. William D. Clinite Chair. Prior to joining the Symphony, she served as assistant principal oboe in the Atlanta Symphony and principal oboe in the Honolulu Symphony.

We thank these wonderful musicians for their many years of service to the San Francisco Symphony and we wish them well.

Community Connections

OMI Cultural Participation Project

The OMI Cultural Participation Project in San Francisco (OMI-CPP) is a nonprofit designed to promote and support the preservation, celebration, and practice of the traditional culture of San Francisco District 11’s diverse communities. OMI-CPP seeks to foster collaborations between community members and organizations to create opportunities for cultural exchange, education, and celebration. Centering dignity and humanity, OMI-CPP strives to make a difference in the Black, Brown, and multicultural community in Ocean View, Merced Heights, Ingleside (OMI) and surrounding neighborhoods, by contributing resources to nonprofit organizations that serve the community, encouraging community building, civic engagement, philanthropy, volunteering, and community stewardship, and providing cultural experiences for members of the community. For more information, visit omicpp.org.

OMI-CPP: “We Rise By Lifting Others”

Meet the Musicians

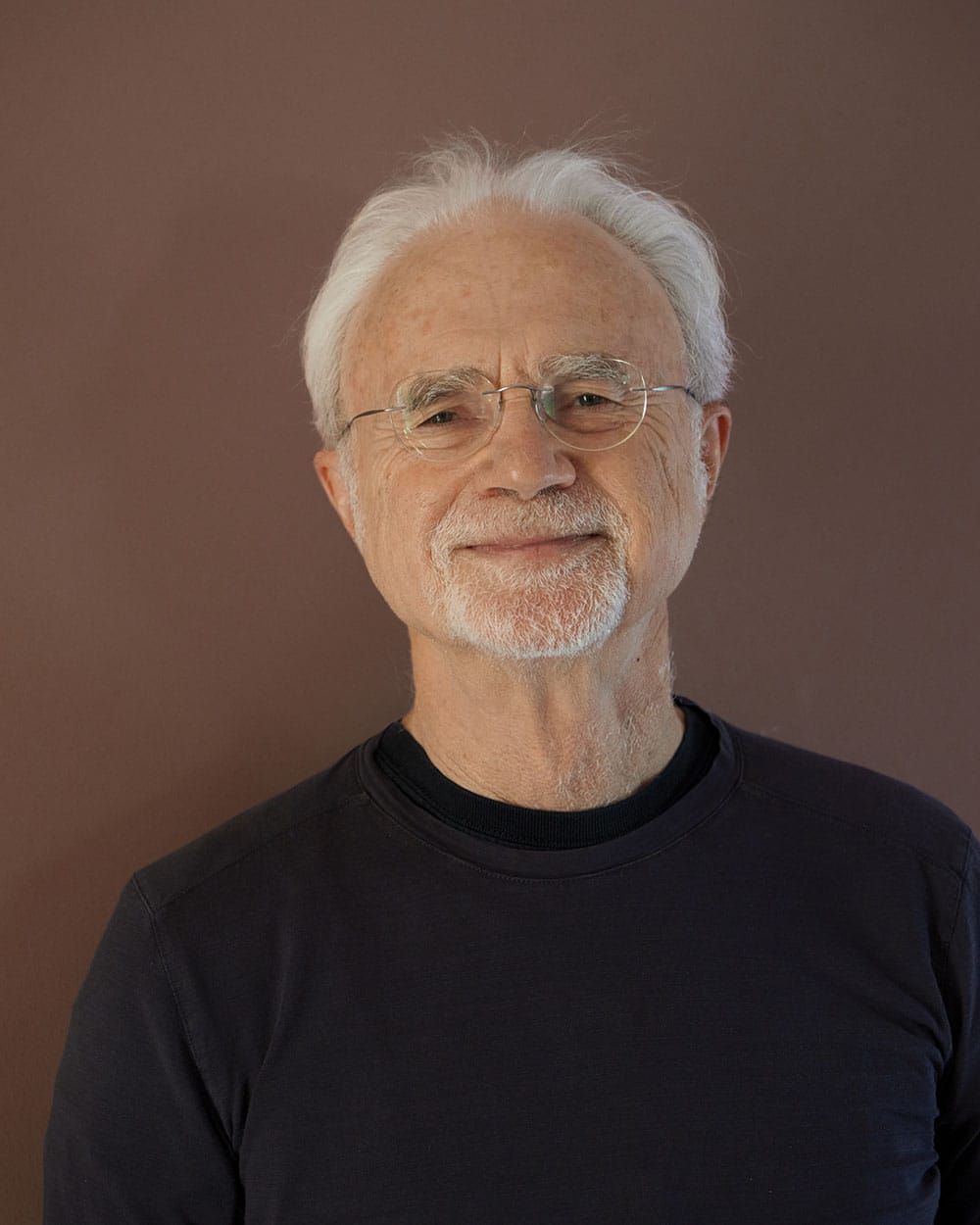

Rainer Eudeikis, Principal Cello • Philip S. Boone Chair

Rainer Eudeikis joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Cello in 2022. He was previously principal cello of the Atlanta Symphony and Utah Symphony, and has performed in the same role for the Mainly Mozart Festival and Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music. Born in Texas and raised in Colorado, he holds degrees from the University of Michigan, Indiana University, and the Curtis Institute of Music.

Do you remember the first concert you played with the San Francisco Symphony?

I do, because it was my trial week in February 2022. It was Beethoven’s Creatures of Prometheus with Maestro Salonen on the podium. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t stressful, but in a way it was also exciting and gratifying because the huge cello solo in that piece is often found on audition lists, but very rarely actually performed. It was nice to have the opportunity to play it in context.

How did you begin playing the cello?

I started when I was six years old. My mom is a professional clarinetist who grew up in Texas public school band programs but always wished she had played a string instrument. When I reached an age where it was time to start playing something, she planted the idea in my head that I would play with cello. I’m sure it seemed like my idea at the time!

Did you have any especially influential teachers?

I have had several. My final teacher in high school was Jurgen de Lemos, who was principal of the Colorado Symphony. He had been the youngest member of the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein before that, and he studied with many of the most iconic 20th-century cellists including André Navarra, Leonard Rose, and Gregor Piatigorsky. At Indiana University I studied with Eric Kim, who was the principal of the Cincinnati Symphony for 20 years and is my primary mentor. I was also fortunate to work with Carter Brey who is principal cello of the New York Philharmonic, and Richard Aaron, too, who was my undergraduate professor at the University of Michigan. I spoke with or played for all of them in preparation for the audition in San Francisco.

Beyond sitting at the front of the section, what are the responsibilities of the principal cello?

I’m a member of the cello section first and foremost, but my responsibility is to be a leader and to advocate for us all. I facilitate the often unspoken communication from the conductor and other sections to the rest of the cello section, and I do my best to keep everything flowing and in sync.

What is your concert day routine?

It varies, but usually I’m at the hall in a practice room an hour before the show. I like to get in the zone, warm up, and feel at home backstage.

Can you tell us a little about your life outside the Symphony?

I moved here from Atlanta with my wife, our then-13-month-old daughter, and two giant dogs. My wife, Joyce, is also a very fine cellist. Family time keeps us very busy, but we are enjoying gradually getting to know the Bay Area and look forward to making our home here.

Print Edition