In This Program

- The Concert

- Brooding, Screaming: Music Makes a Classic

- About the Artist

- Additional Reading

- About San Francisco Symphony

The Concert

Thursday, October 31, 2024, at 7:30pm

Scott Terrell conducting

San Francisco Symphony

PGM Productions

Psycho

Cast

Anthony Perkins Norman Bates

Vera Miles Lila Crane

John Gavin Sam Loomis

Martin Balsam Milton Arbogast

John McIntire Deputy Sheriff Al Chambers

Simon Oakland Dr. Fred Richmond

Vaughn Taylor George Lowery

Frank Albertson Tom Cassidy

Lurene Tuttle Mrs. Chambers

Patricia Hitchcock (as Pat Hitchcock) Caroline

John Anderson California Charlie

Mort Mills Highway Patrol Officer

Janet Leigh Marion Crane

Screenplay by

Joseph Stefano

Robert Bloch

Directed by

Alfred Hitchcock

Music by

Bernard Herrmann

A Universal Picture

Production Credits

Producer: John Goberman

Music Consultant: John Waxman

The producer wishes to acknowledge the contributions and extraordinary assistance of John Waxman (Themes & Variations).

This is a production of PGM Productions, Inc. (New York), and appears by arrangement with IMG Artists.

Brooding, Screaming: Music Makes a Classic

The composer Bernard Herrmann and film director Alfred Hitchcock enjoyed a legendary collaboration. Their partnership lasted from 1955 until 1966, and along with Psycho it included The Trouble With Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Wrong Man, North by Northwest, Vertigo, The Birds (a film that included no music, but on which Herrmann served as “sound consultant”), Marnie, and Torn Curtain.

Herrmann understood film, and the role a composer could play. “With very few exceptions,” he said in an interview shortly before he died, “a film cannot come to life without the help of music of some kind.” And again: “A film is only made of segments of film that are put together. . . . It is the function of music to cement these pieces into one design [so] that the audience feels that their sequence is inevitable.” Among the directors (other than Hitchcock) lucky enough to have taken advantage of his talent for cementing the pieces into one design were Orson Welles, for whom Herrmann wrote his first film score (for Citizen Kane), Robert Wise (The Day the Earth Stood Still), Brian de Palma (Sisters and Obsession), François Truffaut (Fahrenheit 451 and The Bride Wore Black), and Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver).

Herrmann was Manhattan-born (on June 29, 1911), bred, and educated. He emphasized his pride in his country’s musical heritage by becoming one of the earliest champions of Charles Ives. The sound of Herrmann’s film music, as Alex Ross has pointed out, is uniquely lean and American, very different from the lush textures that a cadre of Viennese-trained composers created during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Herrmann wrote and conducted music for radio, including some for the infamous Mercury Theater broadcast of October 30, 1938, Orson Welles’s dramatization of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, which panicked millions who mistook it for a news broadcast alerting the country to a Martian attack. Herrmann would write for television, too, including music for such staples as Gunsmoke and Perry Mason.

Herrmann longed to be taken seriously by the music establishment. He always gave 110 percent to his film work, but he focused on more “serious” projects as well. He wrote a cantata on Moby Dick. He wrote a symphony. For years he labored on an opera, Wuthering Heights, that he never saw produced. Thoroughly American as he was, he also loved England and all things English, especially the music of Edward Elgar, whose Falstaff was among his favorite concert works. When he died in Los Angeles on December 24, 1975, music lovers and film buffs alike knew they had lost a master who had contributed to both mediums.

Possessing an uncanny sense of how to underline the emotional content of the screen sequences he scored, Herrmann knew how to work with the celluloid image to build and release tension. Psycho remains among the most terrifying of all motion pictures. In his score (for strings alone), Herrmann helped make it that way. As the shower curtain is torn back and Marion Crane stares fate in the eyes, we hear instrumental screams burst from the soundtrack, just as our own screams rise in our throats. But Herrmann’s Psycho music can also threaten to suffocate with brooding, claustrophobic passages, such as those that communicate Marion’s hopelessness in the ashen city of Phoenix, where the film opens. Sometimes restrained and sometimes manic, the music traces the major dramatic turns of a story so well-known it has become almost archetypal.

David Thomson, in his study The Moment of Psycho (published by Basic Books in 2009), credits the music with much of the film’s impact, the element that convinced early viewers that here Hitchcock was determined to create not just a sensational movie, but a work of art. Herrmann, writes Thomason, helps carry the picture “past realism and into mythology.“ He also relates this story: “One of the editors on the film, Terry Williams, recalled the day the first score was laid in as a track. Like archaeologists retrieving shards of bone, the editors had pored over the details of slaughter and lost sight of it. With the music, suddenly they were screaming as if the film were new.”

—Larry Rothe

About the Artist

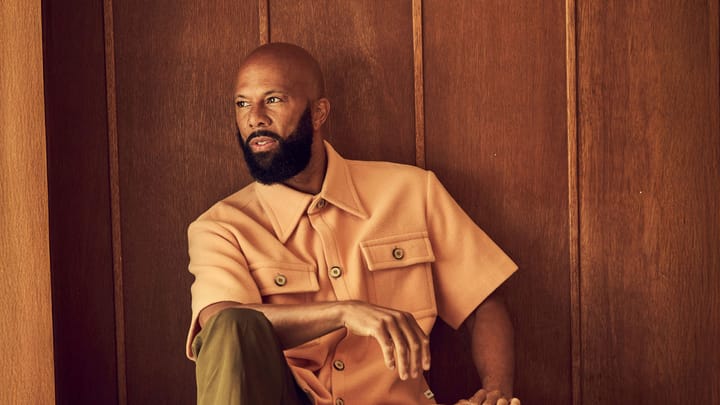

Scott Terrell

Scott Terrell is associate professor of orchestral studies at Louisiana State University, where he holds the Virginia Martin Howard Chair. He was previously music director of the Lexington Philharmonic in Kentucky, where the orchestra won multiple Copland Awards for his dedication to contemporary American composers. He also served as resident conductor and director of education for the Charleston Symphony in South Carolina, and was assistant conductor of the Minnesota Orchestra. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut this week with Psycho.

As a guest conductor, Terrell has appeared with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, Houston Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Vancouver Symphony, Rotterdam Philharmonic, and Hong Kong Sinfonietta. He has been a regular guest conductor and teacher at the Aspen Music Festival since 2001, where he leads concerts and mentors conducting students.

On the opera stage, Terrell has led Kentucky Opera in Stephen Paulus’s oratorio To Be Certain of the Dawn, Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti, Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, and Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar. He has also conducted Opera Hong Kong’s gala concert, Arizona Opera’s production of The Magic Flute, and led Piazzolla’s Maria de Buenos Aires at Fort Worth Opera, Arizona Opera, and Aspen.