In This Program

The Concert

Friday, September 27, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, September 28, 2024, at 7:30pm

Preconcert conversation with composer Nico Muhly: on stage at 6:30pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Paul Hindemith

Ragtime (Well-Tempered) (1921)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Nico Muhly

Piano Concerto (2024)

I.

II.

III.

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Alexandre Tharaud

Intermission

Johann Sebastian Bach

(orch. Edward Elgar)

Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537 (orch. 1921)

Paul Hindemith

Symphony, Mathis der Maler (1934)

(Mathis the Painter)

The Angelic Concert

The Entombment

The Temptation of Saint Anthony

These performances of Nico Muhly’s Piano Concerto for Alexandre Tharaud are supported by the Paul L. and Phyllis C. Wattis Endowment for New Music.

Alexandre Tharaud’s appearance is generously supported by the Shenson Young Artist Debut Fund.

The commissioning of Nico Muhly’s Piano Concerto for Alexandre Tharaud is supported by the Ralph I. Dorfman Commissioning Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Ragtime (Well-Tempered)

Paul Hindemith

Born: November 16, 1895, in Hanau, near Frankfurt

Died: December 28, 1963, in Frankfurt

Work Composed: 1921

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: flute, 2 piccolos, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, snare drum, bass drum, and xylophone), and strings

Duration: About 4 minutes

Paul Hindemith sowed plenty of wild oats during his apprentice years as a composer. In 1921 he included a fire siren and a canister of sand in the instrumentation for his Kammermusik No. 1 and provoked scandal by parodying both the words and music of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in his lurid comic opera Das Nusch-Nuschi. But he was a man of wide-ranging musical interests, and already by that time he was embarking on a lifelong fascination with considerably earlier music, an interest that would lead him to develop expertise as a virtuoso on the Baroque-era viola d’amore. He would make important contributions to reviving early music—producing, for example, an edition of Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo for a production he led himself—and serving for some years as the head of the Yale Collegium Musicum, which explored Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque repertoire.

As a youngster, Hindemith worked through Baroque scores as a fledgling violinist at Berlin’s Hoch Conservatory. There he played the imposing Chaconne from Bach’s D-minor Partita at a semester-end recital in 1911. His admiration for Bach never waned. In 1952 he published an extended lecture he had originally delivered at a Bach commemoration in Hamburg: Johann Sebastian Bach—Heritage and Obligation. In it he complained that biographers had so deified Bach that “he became the banal figure which meets our eyes every day: a man in a full-skirted coat, with a wig he never lays by.” But thanks to recent research, he argued, “the mythical being is beginning slowly to change back into a human being.”

Years earlier, Hindemith had written Ragtime (Well-Tempered), an off-the-cuff piece with versions for piano four-hands or orchestra, the latter waiting until 1987 to be premiered. “Can you also use Fox-trots, Bostons, Rags, and other kitsch?” he had queried his publisher in 1920. “If I cannot think of any decent music, I always write such things.” He felt that Ragtime (Well-Tempered) suggested how Bach might have composed if he lived in 20th century. “If Bach had been alive today,” he wrote, “he might very well have invented the shimmy or at least incorporated it in respectable music. And perhaps, in doing so, he might have used a theme from the Well-Tempered Clavier.” This is a naughty musical prank in which jazzy modernism of a sarcastic sort serves as the framework in which the subject of the C-minor Fugue from Book One of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier is buffeted about—the musically sacred in surroundings most profane.

—James M. Keller

Piano Concerto

Nico Muhly

Born: August 26, 1981, in Vermont

Work Composed: 2024

SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets (2nd doubling E-flat clarinet), bassoon, contrabassoon, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangles, Chinese cymbal, chimes, tam-tam, snare drums, tenor drum, kick drum, bass drum, bowed crotales, glockenspiel, bowed vibraphone, and marimba), harp, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 22 minutes

Born in Vermont and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, Nico Muhly has written for the concert hall, stage, and film. He majored in English at Columbia University before studying at the Juilliard School and working for eight years as an assistant to Philip Glass. Muhly has twice been commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera, resulting in Two Boys in 2011 and Marnie in 2018. Other commissioners include the Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Tallis Scholars, and Carnegie Hall. His music can be heard on the artist-run label Bedroom Community, as well as on Decca and Nonesuch.

With the San Francisco Symphony, Muhly served as a Collaborative Partner, composing Throughline in 2020, whose virtual premiere and release on SFS Media was nominated for a Grammy Award. In 2023 he curated a SoundBox program entitled Codes, which featured pianist Yuja Wang and was taken on tour with the SF Symphony to the Paris Philharmonie and Hamburg Elbphilharmonie.

Muhly’s Piano Concerto is an SF Symphony commission, written especially for pianist Alexandre Tharaud and Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen. Having previously written concertos for cello (2012), viola (2014), organ (2017), violin (2019), and two pianos (2020), this is his first solo piano concerto.

The Music

“I have been obsessed with Alexandre Tharaud for years,” Muhly said in a recent interview with the San Francisco Symphony. Setting out to write a concerto for the pianist, he “went on a major listening binge of his entire catalogue, starting with his wonderful recording Versailles, and it entered my bloodstream in a way that I wasn’t expecting.”

That album features French Baroque music by François Couperin (1668–1733) and Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), among other lesser-known composers who served the courts of Louis XIV and XV. Besides being a composer, Rameau was also the author of the 1722 Treatise on Harmony that revolutionized music theory. Enduring concepts of tonal music, like the idea that the lowest pitch of a root-position chord establishes its fundamental sound and name, were first systematized by Rameau, who was influenced by the scientific work of René Descartes and Isaac Newton. Perhaps growing from that Enlightenment ethos, Muhly hears a kind of musical dualism in Rameau: “a tension between the mechanism of the thing and the soul of the thing. . . there’s a sense of a windup toy that you let do what it does, and also a lyrical possibility.”

All this bled into Muhly’s Piano Concerto, which is set in three connected movements that go fast-slow-fast. “I thought that the first movement should come explicitly from Couperin and Rameau,” Muhly said. “There’s both a harmonic stability and instability, and there are lots of opportunities for ornamentation, which is not something that often comes up in my music.”

The second movement embraces an incredible simplicity for the piano, but the orchestra smears its accompaniment, eventually growing ugly and menacing in the face of the soloist. Finally it recedes into a coda that repeats a few chords borrowed from Rameau—another toylike touch.

The third movement, Muhly says, is just meant to be bright and dazzling. It incorporates little memories of French music—but “you’re meant to sort of smell them, not hear them.” This connects to Muhly’s preoccupation—not with influence, exactly—but with how we live in the present with the music of the past. “It’s thinking about the music that haunts us even when we don’t think about it. The music which you carry around with you all the time, without knowing that you’re thinking about it.”

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537

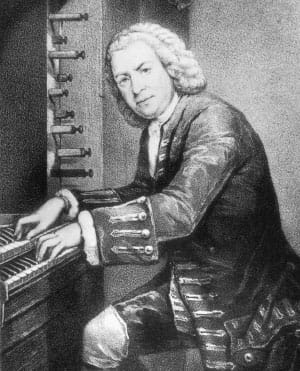

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: March 21, 1685, in Eisenach, Germany

Died: July 28, 1750, in Leipzig

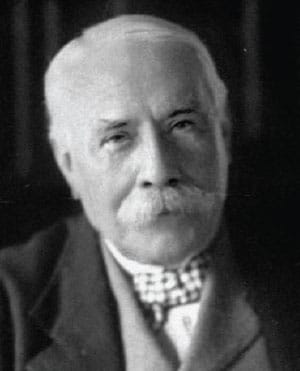

Edward Elgar

Born: June 2, 1857, in Broadheath, near Worcester, England

Died: February 23, 1934, in Worcester

Work Composed: ca. 1710s–20s (orch. 1921)

SF Symphony Performances: First and only—October 1984.

George Cleve conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tambourine, snare drum, bass drum, and glockenspiel), 2 harps, and strings

Duration: About 8 minutes

Edward Elgar spent his teenage years developing into a capable organist and spent as much time as he could absorbing music at Worcester Cathedral. The organ sonata he composed in 1895 included some passages likely to be heard as Bachian, and he told an interviewer that year, “I play three or four preludes and fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier every day.” He made considerable effort to catch performances of the Leipzig master’s music, which were far less frequently encountered then than they are now. A Brandenburg Concerto he heard in Cologne—we know not which—left an indelible impression that he recalled in later communications with friends, and he was fanatical about the Bach interpretations of violinist Fritz Kreisler.

Following his wife’s death, in 1920, Elgar sought solace in the Well-Tempered Clavier and revisited the Bach organ fugues he had mastered as an organ scholar decades earlier. “Now that my poor wife has gone I can’t be original,” he told the conductor Eugene Goossens, “and so I depend on people like John Sebastian for a source of inspiration.” This led to a further Bach arrangement. He wrote to his organist friend Ivor Atkins that he had decided to orchestrate Bach’s four-voiced Organ Fugue in C minor “in modern way—largish orchestra. . . . So many arrgts [arrangements] have been made of Bach on the ‘pretty’ scale & I wanted to shew how gorgeous & great & brilliant he would have made himself sound if he had our means.” In a letter to the critic Ernest Newman, Elgar indicated that he was guided to some extent by how the piece might be played on the organ, but really, this is more of a symphonic work-out, replete with full complements of woodwinds and brasses, plus, for good measure, such decidedly un-Bachian touches as harps, triangle, tambourine, and cymbals.

Elgar completed his orchestration on April 25, 1921, and Goossens conducted its premiere on October 27 at Queen’s Hall, London. In January 1922 his old friend Richard Strauss visited England and Elgar hosted him at a luncheon to meet up-and-coming British composers, including John Ireland, Arthur Bliss, and Arnold Bax, with music critic and playwright George Bernard Shaw offering remarks. At the lunch, Elgar and Strauss discussed the question of orchestrating Bach. Strauss (hardly a prude when it came to orchestration) felt that Elgar’s arrangement went a bridge too far, at which Elgar threw down the gauntlet. Let Strauss orchestrate the Fantasia that Bach had attached as a preamble to this fugue, he suggested, and then listeners could experience the different approaches of the two composers. Strauss may have expressed some interest, or perhaps he just played along out of politeness. He never followed up on the idea, and Elgar decided to orchestrate the Fantasia himself, conducting the premiere of the Fantasia and Fugue together at the Gloucester Festival in September 1922.

—J.M.K.

Symphony, Mathis der Maler

(Mathis the Painter)

Paul Hindemith

Work Composed: 1933–34

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1944. Pierre Monteux conducted. Most recent—November 1987. Herbert Blomstedt conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, orchestra bells, snare drum, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 25 minutes

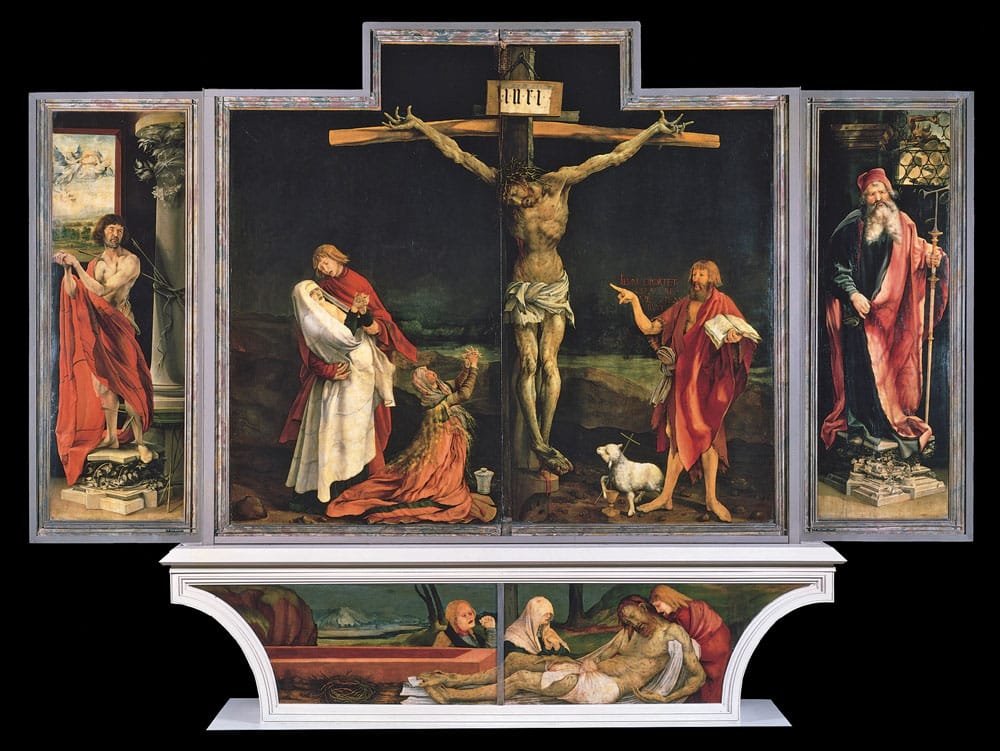

Paul Hindemith’s uninhibited explorations were severely curtailed after 1933. In the wake of the Nazi upsurge, he composed a series of vocal works setting melancholy, even despairing, texts. These exemplify the “inner emigration” shared by a number of similarly disaffected German artists at that time, and many of these works were not released for performance until years later. Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler towers among them. Its title character—Mathis the Painter—is the German artist known as Matthias Grünewald (ca. 1470–1528). Like Hindemith, Grünewald lived in troubled times: his sympathy with uprisings by German peasants cost him the support of the Cardinal-Archbishop of Mainz, which, in turn, impacted the sorts of artistic projects he could pursue. He had rested in oblivion for centuries when his work was rediscovered in the 1920s. Since then, his Isenheim Altarpiece, painted for a monastery in Alsace but now residing in the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar, France, has become one of the most famous images in all of art.

Hindemith was deeply touched by Grünewald’s situation, sensing its relevance to the Germany of four-plus centuries later. From July 1933 through July 1935, he crafted the libretto and music for his opera on the subject, Mathis der Maler, which evolved into a three-hour work comprising a prologue and seven ensuing scenes. It was in the midst of this project that Hindemith’s standing crashed officially, leading to the blacklisting of his music and the impossibility of producing the opera in Frankfurt, as had been planned. In the event, it was first seen in Switzerland, at the Zurich Stadttheater, in 1948.

In 1933, the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler asked Hindemith to write a piece he could premiere with the Berlin Philharmonic. Hindemith responded with the idea of creating a four-movement Mathis der Maler Orchestral Suite employing symphonic passages that he had already sketched, or intended to write anyway, for his opera. In the end he decided to call it a symphony and limit the movements to three, each depicting a different section of the Isenheim Altarpiece. The Mathis der Maler Symphony was one of the composer’s last successes before the tide turned against him, but it was a resounding one. He himself led the Berlin Philharmonic in a recording for the German Telefunken label shortly after the premiere, which took place on March 12, 1934, in Berlin, with Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic.

The Music

The first movement, Engelkonzert (The Angelic Concert), is inspired by a scene of the altarpiece in which the Virgin and Child are serenaded by a host of angels playing fanciful instruments. (In the opera this music serves as an overture and resurfaces later in somewhat different form.) Its solemn introduction makes use of the German folk-song “Es sungen drei Engel ein’ süssen Gesang.” Mahler had drawn on the same folk song in the choral fifth movement of his Third Symphony, taking its text from the famous 19th-century German poetic collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Here we encounter Hindemith’s love of brass timbres, as in the chorale-like intonations that follow the fugal development in this opening movement.

The second movement, based on Grünewald’s “The Entombment,” serves as an interlude in the opera’s final tableau. The music builds from the flute’s tender melody at the opening through a procession of increasing power to a solemn but grand climax, again with a firm brass presence; and then it recedes to quiet contemplation.

The “Temptation of Saint Anthony” music occurs as a sequence of hallucinations in Scene Six, during which the painter imagines himself to be the hermit Saint Anthony, confronted by a series of characters from Mathis’s past. “Ubi eras bone Jhesu / ubi eras, quare non affuisti / ut sanares vulnera meas?” Hindemith has inscribed at the head of this finale, words transcribed from the altarpiece itself: “Where were you, good Jesus, where were you? Why have you not come to heal my wounds?” St. Anthony’s triumphant fate is mirrored in a concluding chorale prelude on the chant “Lauda Sion Salvatorem” (Praise the Savior, O Zion).

—J.M.K.

About the Artists

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

Alexandre Tharaud

This season Alexandre Tharaud performs music of Maurice Ravel, marking the 150th anniversary of the composer's birth, with the Aurora Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Finnish Radio Symphony, Aarhus Symphony, Orchestre National de Montpellier, Beethoven Orchestra Bonn, and Orchestre National de Belgique. Further concerto highlights include Orchestre Metropolitain, George Enescu Philharmonic, Brno Philharmonic, and South Netherlands Philharmonic. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

The breadth of Tharaud’s artistic endeavors is also reflected in collaborations with theater makers, dancers, choreographers, writers, and filmmakers, as well as with singer-songwriters and musicians outside the realm of classical music. As an exclusive recording artist for Warner Classics, his recent disc of Ravel’s piano concertos has received critical acclaim, and he has also made recordings of works by Rameau and Scarlatti, Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Italian Concerto, Beethoven’s late piano sonatas, Chopin’s Preludes, and Ravel’s complete piano works.

In 2017 Tharaud published Montrez-moi vos mains (Show Me Your Hands), an introspective and engaging account of daily life as a pianist. He previously coauthored Piano Intime with journalist Nicolas Southon. He is the subject of the film Alexandre Tharaud, Le Temps Dérobé (Stolen Time), directed by Raphaëlle Aellig-Régnier, and appeared in Michael Hanneke’s 2012 film Amour.