In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, February 9, 2025, at 7:30pm

Seong-Jin Cho piano

MAURICE RAVEL

Complete Works for Solo Piano

Sérénade grotesque (c. 1893)

Menuet antique (1895)

Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899)

Jeux d’eau (1901)

Sonatine for Piano (1905)

Modéré

Mouvement de menuet

Animé

Intermission

Miroirs (1905)

Noctuelles

Oiseaux tristes

Une Barque sur l’océan

Alborada del gracioso

La Vallée des cloches

Gaspard de la nuit (1905)

Ondine

Le Gibet

Scarbo

Intermission

Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn (1909)

Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911)

Modéré–très franc

Assez lent–avec un expression intense

Modéré

Assez animé

Presque lent–dans un sentiment intime

Vif

Moins vif

Épilogue: lent

Prélude (1913)

À la manière de Borodine (1913)

À la manière de Chabrier (1913)

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917)

Prélude

Fugue

Forlane

Rigaudon

Menuet

Toccata

Presenting Sponsor of the Great Performers Series

Program Notes

Complete Works for

Solo Piano

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

We salute Maurice Ravel in this year of his 150th birthday. He began piano lessons at the age of seven, and five or six years later he began producing his first compositions, which were scored (not surprisingly) for piano. Following piano study in the Paris Conservatory’s preparatory division, he gained admission to the Conservatory itself as a piano major. Although he was a capable pianist, he did not display the keyboard panache required of a top-flight concert virtuoso at the turn of the 20th century. He left the school in 1895 but returned in 1897 to study composition with Gabriel Fauré and counterpoint and fugue with André Gédalge, both of whom he acknowledged as formative mentors. He failed (after five attempts) to secure the Prix de Rome, the distinction that served as a seal of approval for emerging composers. This set off a scandal, ballyhooed in the press as L’affaire Ravel, that led to a shake-up in the Conservatory’s administration, although Ravel himself accepted the situation with the equanimity that became his hallmark.

Already in the late 1890s he wrote such still-performed piano works as his Menuet antique and Pavane pour une infante défunte. His output of piano music remained steady through 1917, and in the 1920s he transcribed some of his orchestral pieces into versions for solo piano or piano duet. Despite his limited success as a concert figure early on, he revved up his touring schedule in the 1920s and early 1930s; but by that time, accounts of his playing almost unanimously acknowledged inaccuracies. “He made lots of mistakes—that was because he didn’t practice enough,” recalled the Spanish composer Ernesto Halffter. “But he gave a very good idea of what he meant. I prefer Ravel with mistakes to anyone else without them.” In his more virtuosic movements, like Alborada del gracioso, Ondine, and Scarbo, he made pianistic demands he could not meet himself. Such pieces are rich in rapidly repeated notes, parallel glissandos, leaping left-hand arpeggios, and other technical complications that must be integrated into the poetic flow.

Tonight’s recital presents Ravel’s complete works for solo piano in chronological order. It does not include pieces that he arranged from pre-existing orchestral works, like Daphnis et Chloé or Boléro, but symphony regulars will recognize pieces that achieved matching fame in his expansions for orchestra, such as Valses nobles et sentimentales or portions of Le Tombeau de Couperin.

Early Works

First up is Sérénade grotesque, written in or about 1893, when Ravel was in the midst of his studies. He said that this brief work reflected the influence of Emmanuel Chabrier, but one does already spy adumbrations of the later Ravel, including touches of Spanish flavor. After Ravel played it in his harmony class, the professor remarked, “All this produces a most unusual impression, as if you’re riding mounted on a chimera. You must rein in your thoughts and take fewer liberties. But who knows? Maybe one day you will present us with a new style.” Menuet antique followed in November 1895, and in 1898 it became Ravel’s first published work, its red-and-black cover graced by an elaborate illustration in arts-and-crafts style reminiscent of William Morris. Written in the style of a dance “of olden times,” the piece was premiered by and dedicated to the intrepid Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, a classmate at the Conservatory, who would go on to give the first performances of Jeux d’eau, Miroirs, and Gaspard de la nuit.

Ravel apparently unveiled his Pavane pour une infante défunte at the socially stratospheric Paris salon of the Princesse de Polignac in 1899, although its public premiere (by Viñes) would not take place until a few years later. Its title is usually rendered in English as “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” but it’s a poor translation. Ravel pointedly uses the word “Infante” rather than “Princesse,” and there is no reason not to employ the closer translation of “Infanta,” redolent of a rather exotic form of Iberian aristocracy. In fact, the title was selected for the sound of the words rather than their meaning. The critic Alexis Roland-Manuel quoted him as insisting, “When I put together the words that make up this title, my only thought was the pleasure of alliteration.” A piece that everybody recognizes instantly, its emotional coolness and restrained melancholy lend it a unique personality.

Jeux d’eau—it means “fountains” but the French term conveys something more vibrant, literally water at play. Ravel wrote: “Jeux d’eau, which appeared in 1901, marks the beginning of all the pianistic innovations which have been noted in my works. This piece, inspired by the sound of water and the musical sounds made by fountains, cascades, and streams, is based on two themes, like the first movement of a sonata, without, however, submitting to the classical tonal scheme.” Claude Debussy, with whom Ravel enjoyed a cautious relationship, observed, “This piece on butterflies’ wings cannot bear the weight (or, if you prefer, the foot) of virtuosos.”

“Les Apaches” was the fanciful name adopted by a high-spirited group of Parisian musicians, poets, and artists who, from the turn of the century until the onset of World War I, gathered on Saturday evenings to share their latest work, discuss cultural news, and do whatever else creative types do on weekends. Viñes proposed the name, and other regulars included composers André Caplet, Maurice Delage, Manuel de Falla, Florent Schmitt, and Déodat de Severac, in addition to Ravel, who tried out both Jeux d’eau and the Sonatine (1903–05) at the group’s get-togethers. A small-scaled, delicate piece of clearly delineated structure and condensed melodic range, the Sonatine showed how a classical form could still serve for original expression—this at a time when old-fashioned sonata forms seemed hopelessly played out and composers were eager to break traditional molds rather than figure out how to work within them.

Maturity

With the multi-movement suites Miroirs (Mirrors, 1904–05) and Gaspard de la nuit (Gaspard of the Night, 1908) we enter Ravel’s full maturity as a piano composer. Both comprise miniature tone poems born from, or at least attached to, extra-musical inspiration. Miroirs, said Ravel, “marks a rather considerable change in my harmonic evolution that baffled even the musicians who were most accustomed to my style.” Each of the five movements was dedicated to a different Apache member, beginning with poet Léon-Paul Fargue. Noctuelles (Owl-moths) was inspired by a line from a poem of his: “The owl-moths leave the sheds in awkward flight, to cling to other rafters.” Ravel described Oiseaux tristes (Sad Birds) as “birds lost in the torpor of a very dense forest during the hottest hours of summer,” and legend has it that impetus came from hearing a blackbird in the Forest of Fontainebleau. Une barque sur l’océan (A Boat on the Ocean) is marked “with supple rhythm” and lacks a metronome tempo indication; “Ravel did not trust the swell of the ocean,” observed his pianist-friend Hélène Jourdan-Morhange. Alborada del gracioso (The Jester’s Morning Song), one of Ravel’s Spanish-flavored works, became immensely famous through the 1918 orchestration he made for impresario Serge Diaghilev to use as a ballet. (Less well known is his 1906 orchestration of Une barque sur l’océan.) The earthy accents of the Alborada make the serenity of La vallée des cloches (The Valley of the Bells) all the more striking, its bell-like sonorities tolling against a mysterious background.

Each movement of Gaspard de la nuit is printed alongside a prose poem by Aloysius Bernard, whose only book, Gaspard de la nuit: Fantasies in the Manner of Rembrandt and Callot, was published posthumously in 1842. The original edition sold only 20 copies, but he would eventually be embraced as a precursor of symbolism and surrealism. Ravel’s music corresponds to Bernard’s texts point-for-point. Ondine evokes a water-sprite whose love is spurned by a mortal; Le gibet (The Scaffold) is creepy and death-infused, played with the soft pedal down throughout; and Scarbo is a nighttime imp who dashed about until “his face turned pale like the stump of a candle . . . and suddenly he expired.” Apart from the imagery, Scarbo also gives pianists nightmares for musical reasons, being sometimes cited as the single most difficult piece in the standard solo-piano literature. For his part, Ravel largely withheld comment, describing the suite as “a set of three Romantic poems of transcendental difficulty.”

Later Pieces

Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn (Minuet on the Name of Haydn, 1909) was Ravel’s two-minute contribution to a collective project (along with Debussy, Dukas, d’Indy, Hahn, and Widor) undertaken for the centennial of Haydn’s death. The letters of Haydn’s name are rendered through a cryptographic process as musical notes, which Ravel’s graceful tribute incorporates straight-on, in reverse, and upside-down.

The idea for Valses nobles et sentimentales (Noble and Sentimental Waltzes, 1911) came from two groups of piano pieces by Schubert: the 12 Valses nobles (D.969) and the 34 Valses sentimentales (D.779), cherished more as private amusements for the studio or salon than as items for the concert stage. That Ravel envisaged a similar mood for his Valses nobles et sentimentales is clear from the words he placed at the top: “the pleasure, delightful and ever new, of a useless vocation,” borrowed from Belle Époque poet and novelist Henri de Régnier. It stands as a perfect epigram for Ravel’s eight waltzes—or, to follow his labeling, seven plus an epilogue, one following the other without breaks between. Ravel commented, “After the virtuosity of Gaspard de la nuit comes this sparse, transparent writing in which the harmony is harsher, setting off to advantage the musical outlines.”

Three morsels follow. Prélude (1913) was written for the Paris Conservatory to use for the women’s sight-reading examination that year; one of the students, Jeanne Leleu (half of the two-piano team that had introduced Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye three years earlier), did so well that he dedicated it to her. In his witty À la manière de . . . pieces (1912 or 1913), Ravel did his bit for the then-current fad of writing pastiche-caricatures of other composers. (Alfredo Casella wrote one À la manière de Ravel.) Alexander Borodin was a favorite of our composer—the members of Les Apaches sounded the opening tune of his Second Symphony as a secret signal—and he is here honored with a Russian-sounding waltz. Emmanuel Chabrier was an inveterate musical prankster, and Ravel reflects that by composing an unlikely parody on an aria from Gounod’s Faust.

There remains Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914–17), a product of the World War I years, when Ravel spent time as a driver in the Army Motor Transport Corps. His eagerness to serve may have exceeded his skill behind the wheel, as his correspondence reveals several incidents of one-car fender-benders. Discharged following a health collapse in 1917, he returned to some of the musical projects that had occupied him prior to the war, now revisiting them with an attitude transformed by recent years. When he began sketching this piece, in 1914, he had reported in a letter to a colleague, “I’m beginning . . . a French Suite—no, it’s not what you think—the Marseillaise doesn’t come into it at all but there’ll be a forlane and a gigue; not a tango, though”—the forlane and gigue being court dances from the era of François Couperin (1668–1733). In 1929, Ravel wrote, “In fact, the homage is directed less to Couperin himself than to French music of the 18th century.” His homage took the form of six pieces for solo piano, and by the time Ravel finished it, the work became another sort of memorial, its movements being dedicated to people he knew who were lost during the war, including his mother. The pianist Alfred Cortot, who had admired Ravel deeply since they were piano students together at the Conservatory, wrote, “No glorious monument could honor the memory of the French better than do these luminous melodies, these rhythms that are at the same time distinct and flexible—a perfect expression of our culture and of our tradition.”

—James M. Keller

About the Artist

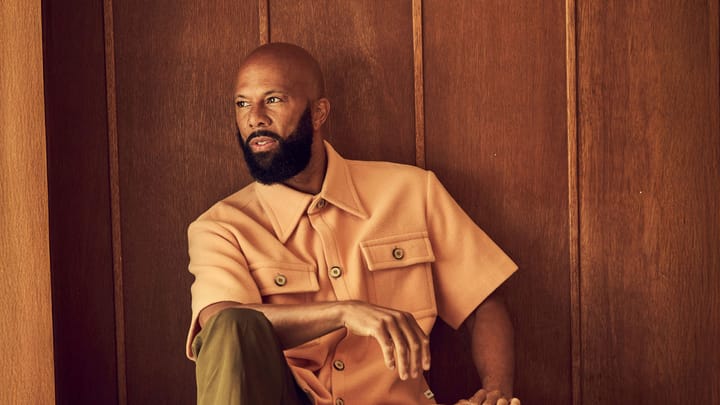

Seong-Jin Cho

Seong-Jin Cho came to the world’s attention in 2015 when he won first prize at the Chopin International Competition in Warsaw. In 2016 he signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and in 2023 was awarded the Samsung Ho-Am Prize in the Arts in recognition of his exceptional contributions to the world of classical music.

This season, Cho is artist in residence with the Berlin Philharmonic, working with the orchestra on multiple projects including concerto performances, chamber music collaborations, recitals, and a tour to the Osterfestspiele Baden-Baden. He also returns to the BBC Proms, Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, and Cleveland Orchestra. He embarks on several international tours, including to Korea with the Vienna Philharmonic, and to Japan, Taiwan, and Korea with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra. In recital, he plays Ravel’s complete solo piano music at the Vienna Konzerthaus, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, the Barbican Centre, Walt Disney Hall, Carnegie Hall, and Boston’s Symphony Hall.

In January, Cho released his recording of Ravel’s complete solo piano works on Deutsche Grammophon, and in 2023 released his album The Handel Project. He has also recorded Chopin’s Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 with the London Symphony and an album titled The Wanderer, featuring Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy alongside works by Berg and Liszt. A solo Debussy recital was also released in 2017, followed by a Mozart album with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.

Born in 1994 in Seoul, Seong-Jin Cho began studying piano at the age of six and gave his first public recital at age 11. In 2009, he became the youngest-ever winner of Japan’s Hamamatsu International Piano Competition. In 2011, at age 17, he won third prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. He first appeared at Davies Symphony Hall on the Great Performers Series in November 2016, touring with the Warsaw Philharmonic, and made his San Francisco Symphony debut in January 2024.