In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, March 2, 2025, at 7:30pm

Yuja Wang piano

Víkingur Ólafsson piano

Luciano Berio

Wasserklavier from Six Encores for Piano (1965)

Franz Schubert

Fantasy in F minor, D.940 (1828)

John Cage

Experiences No. 1 (1945)

Conlon Nancarrow

(arr. Thomas Adès)

Study No. 6 from Studies for Player Piano (ca. 1950s)

John Adams

Hallelujah Junction (1996)

Intermission

Arvo Pärt

Hymn to a Great City (1984)

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphonic Dances, Opus 45 (1940)

Non allegro

Andante con moto (Tempo di valse)

Lento assai—Allegro vivace

Presenting Sponsor of the Great Performers Series

This concert is generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Program Notes

Wasserklavier from Six Encores for Piano

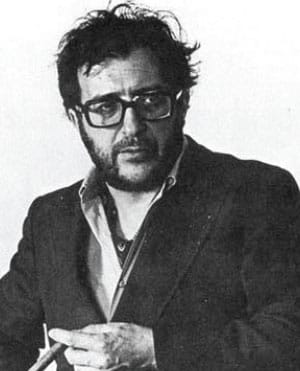

Luciano Berio

Born: October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy

Died: May 27, 2003, in Rome

Work Composed: 1965

Luciano Berio was one of his era’s most intrepid musical explorers, a figure whose work had stayed near the cutting edge of the avant-garde from the 1950s until his passing. Musical quotation and collage resurface almost as leitmotifs in Berio’s output, and he was fond of elaborating on music by other composers, as in his arrangement, re-working, or “over-layering” of pieces by such diverse figures as Purcell, Schubert, Verdi, Brahms, and the Beatles—or, for that matter, folk songs from diverse cultures. Both Schubert and Brahms waft vaguely through Wasserklavier (Water Piano), which reimagines motifs from the former’s Impromptus (D.935) and the latter’s Intermezzi (Opus 117). Berio originally wrote Wasserklavier for solo piano but expanded it into the present version for the piano-duo team of Gold and Fizdale.

Fantasy in F minor, D.940

Franz Schubert

Born: January 31, 1797, in Vienna

Died: November 19, 1828, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1828

Franz Schubert appears to have composed the first two of this astonishing Fantasy’s four connected movements in January 1828 and then finished the full piece that April. The delay may be due to his becoming sidetracked preparing the only public all-Schubert concert of his life, in Vienna in late March. It was far more common for his compositions to be heard at small-scale gatherings, as, indeed, was this one, which Schubert and his colleague Franz Lachner unveiled that May in the presence of their friend Eduard Bauernfeld, probably at his lodgings. Most of Schubert’s distinctive fingerprints are on this work—sudden starts, stops, and changes of mood and direction; bits of canonic imitation; and especially his expansive attitude to tonality that has major and minor modes rubbing shoulders to great expressive effect.

Experiences No. 1

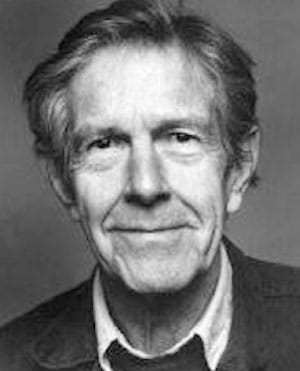

John Cage

Born: September 5, 1912, in Los Angeles

Died: August 12, 1992, in New York

Work Composed: 1945

While growing up in Los Angeles, John Cage made stabs at a formal musical education but didn’t much like what he encountered in the process. At UCLA he attended classes given by no less an eminence than Arnold Schoenberg, who in the end declared, “He is not a composer, but an inventor—of genius.”

Some of those inventions were inspired by the sorts of things another of his teachers, Henry Cowell, was exploring in the development of new piano sonorities. Others bore some resemblance to sounds encountered in non-Western musics, or borrowed from the “music of life” that surrounds everybody every day. When he composed Experiences No. 1, in 1945, Cage had recently become romantically involved with the choreographer Merce Cunningham. Their first joint concert, in April 1944, provoked much enthusiasm among avant-gardists, and many performances followed.

Experiences was unveiled at one of these dance-and-music events, on January 9, 1945, at the Playhouse of New York’s Hunter College; Cunningham was the solo dancer and the pianists were Cage and Mari Ajemian. It unrolls in what we might consider five paragraphs, all based on similar material. The piece, reminiscent of some piano music of Erik Satie, is set in the Aeolian (natural minor) mode and uses only the white keys of the pianos.

Study No. 6 from Studies for Player Piano

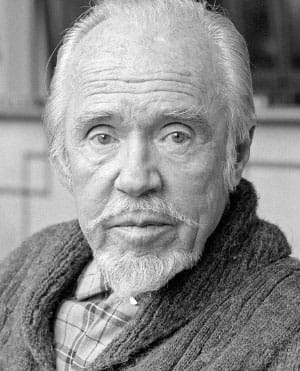

Conlon Nancarrow (arr. Thomas Adès)

Born: October 27, 1912, in Texarkana, Arkansas

Died: August 10, 1997, in Mexico City

Work Composed: ca. 1950s (arr. 1998)

Conlon Nancarrow seemed to be heading toward a more-or-less mainstream career, developing well-honed skill as a classical and jazz trumpeter, spending three years at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, then studying composition privately in Boston with Nicolas Slonimsky, Walter Piston, and Roger Sessions. In 1937 he headed to Spain to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and fight Franco’s fascists; but his socialist leanings made him unwelcome when he returned to the United States, and he decamped to Mexico in 1940, gaining citizenship there in 1956 and remaining for the rest of his life.

Nancarrow was obsessively interested in rhythm, particularly rhythms too complex to be realized by actual musicians, at least at that time. His medium was the player piano, and he punched his music into piano rolls note-by-note. Building on the work of Henry Cowell, he developed previously unimagined polyrhythms and tempo relationships, and he invented a way to correlate metric pulses to pitches. His most notable body of work is his Studies for Player Piano, which he produced beginning in 1948 (they are undated, and their individual origins are largely undocumented). Study No. 6 is one of the few that can be arranged for human pianists, which is not to say that it lacks rhythmic complexity. Here the second piano’s left-hand plays a bouncy habanera-like figure in 5/8 meter, that same pianist’s right hand plays in 4/8 meter, and the first pianist plays in 3/4 meter as the texture gradually expands, then contracts, and, at the very end, explodes into music that occupies five staves. In 1960, this was one of six Nancarrow Studies for which Merce Cunningham created choreography.

Hallelujah Junction

John Adams

Born: February 15, 1947, in Worcester, Massachusetts

Work Composed: 1996

Hallelujah Junction, composed in 1996, took on exceptional importance in the annals of Adamsiana when he used its title as the name for his remarkable memoirs, published in 2008. He explained of the composition:

Hallelujah Junction is a tiny truck stop on Route 49 on the Nevada-California border, not far from where I have a small mountain cabin. . . . Here we have a case of a great title looking for a piece. So now the piece finally exists: the ‘junction’ being the interlocking style of two-piano writing which features short, highly rhythmicized motives bouncing back and forth between the two pianos in tightly phased sequences. . . . Hallelujah Junction lasts approximately 15 minutes and is in four parts, linked one to the other. The first section begins with a short, exclamatory three-note figure which I think of as “-lelujah” (without the opening “Hal-”). This energized, bright gesture grows in length and breadth and eventually gives way to a long, multifaceted “groove” section. A second, more relaxed part is more reflective and is characterized by waves of triplet chord clusters ascending out of the lowest ranges of the keyboard and cresting at their peak like breakers on a beach. A short transitional passage uses tightly interlocking phase patterns to move the music into a more active ambience and sets up the final part. In this finale, the “hallelujah chorus” kicks in at full tilt. The ghost of Conlon Nancarrow goes head to head with a Nevada cathouse pianola.

Hymn to a Great City

Arvo Pärt

Born: September 11, 1935, in Paide, Estonia

Work Composed: 1984 (rev. 2004)

Arvo Pärt staked a defining niche among composers of “the New Spirituality,” a thread of production marked by a minimalist approach to melody, harmony, and rhythm that leads to an austere, contemplative musical product. He grew up in an Estonia that was buffeted between the Soviets and the Nazis during World War II. It stood as a Soviet Socialist Republic until 1991, when the dissolution of the Eastern bloc spelled revived independence. By then, Pärt had left his homeland. In 1980 he and his Jewish wife were granted papers to settle in Israel, but they never made it that far. Touching down at the Vienna airport, they were met by a representative of the music publisher Universal Edition; he arranged for them to stay in Vienna and shortly thereafter move to Berlin, where Pärt remained until he moved back to independent Estonia in 2010. By 1976 he landed on a tonal technique he dubbed “tintinnabuli,” referring to bell-like resonances.

Although Hymn to a Great City does not use the harmonic processes most associated with this style, bell-like sonorities are present throughout in the repeat G-sharps distributed between the two players. The “great city” of the title is New York, where the piece was premiered in 1984 at Lincoln Center by the new-music ensemble Continuum, as part of the first major celebration of Pärt’s work following his emigration to the West.

Symphonic Dances, Opus 45

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born: April 1, 1873, in Semyonovo, Staraya Russa, Russia

Died: March 28, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California

Work Composed: 1940

Sergei Rachmaninoff spent the summer of 1940 at an estate near Huntington, Long Island, and it was there that his final substantial work, the Symphonic Dances, came into being. He initially planned to name the piece Fantastic Dances, which would have underscored its vibrant personality. He also pondered titling the three movements “Noon,” “Twilight,” and “Midnight,” meant as a metaphor for the three stages of human life. The composer scrapped that idea in favor of the more objective name Symphonic Dances. The spirit of the dance does indeed inhabit this work, if in a sometimes mysterious or mournful way.

As Rachmaninoff was completing the piece, he played it privately (in a piano draft) for his old friend Michel Fokine, the one-time choreographer of the Ballets Russes, who immediately signaled his interest in using it for a ballet; regrettably, Fokine died in 1942 before he could make good on his intention. Rachmaninoff also played that draft privately on two occasions (the second being partially captured on a probably surreptitious recording) for conductor Eugene Ormandy, who was preparing to lead the premiere with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

As he was writing the orchestral score, the composer also created a version for two pianos, the score of which is dated August 19, 1940. He apparently felt that it would be appropriate for concert performance. He never performed it publicly, but he did play it with his friend Vladimir Horowitz, with whom he enjoyed convening for private duet sessions. Rachmaninoff’s biographer Sergei Bertensson was present for one of the get-togethers that included the Symphonic Dances. “The brilliance of this performance,” he wrote, “was such that for the first time I guessed what an experience it must have been to hear Liszt and Chopin playing together, or Anton and Nicolai Rubinstein.”

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

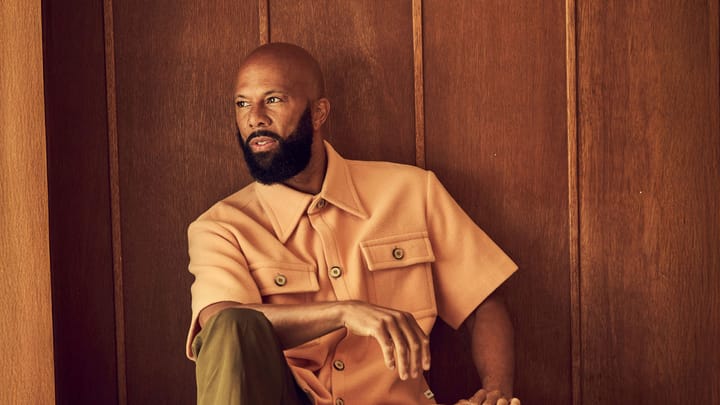

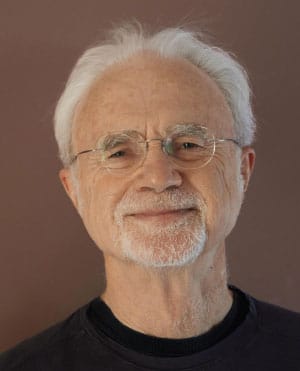

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang has performed with the world’s most venerated conductors, musicians, and ensembles, and is renowned not only for her virtuosity, but her spontaneous and lively performances. Her skill and charisma were recently demonstrated in a marathon Rachmaninoff performance at Carnegie Hall with the Philadelphia Orchestra, including all four of his concertos plus the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. The 2022–23 season also saw Wang performing the world premiere of Magnus Lindberg’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the San Francisco Symphony and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Wang was born into a musical family in Beijing. After childhood piano studies in China, she received advanced training in Canada and at the Curtis Institute of Music under Gary Graffman. Her international breakthrough came in 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich as soloist with the Boston Symphony. Two years later, she signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and has since established her place among the world’s leading artists, with a succession of critically acclaimed performances and recordings. Wang made her San Francisco Symphony debut in February 2006 and became a Shenson Young Artist later that year.

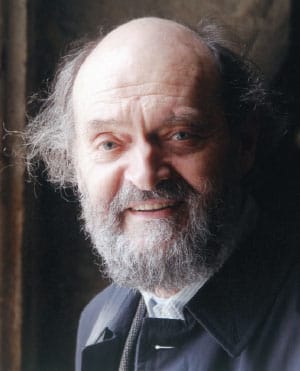

Víkingur Ólafsson

Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson has captured the public and critical imagination with profound musicianship and visionary programs. His recordings for Deutsche Grammophon have led to almost one billion streams and garnered numerous awards, including a recent Grammy for Best Classical Instrumental Solo, BBC Music Magazine Album of the Year, and Opus Klassik Solo Recording of the Year. Other notable honors include the Rolf Schock Music Prize, Gramophone’s Artist of the Year, Order of the Falcon (Iceland’s order of chivalry), as well as the Icelandic Export Award, given by the president of Iceland. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist in June 2022 performing John Adams’s Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?, and premiered Adams’s latest piano concerto, After the Fall, with the SF Symphony in January.

Ólafsson devoted his entire 2023–24 season to a world tour of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, performing it 88 times to great critical acclaim. This season sees Ólafsson as artist in residence with the Tonhalle Zurich and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, as well as “artist in focus” at Vienna Musikverein. He tours Europe with the Cleveland Orchestra, London Philharmonic, and Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, performs with the Berlin Philharmonic at the BBC Proms, and returns to the New York Philharmonic.