June 15–28, 2024

In This Program

- About the Show

- Synopsis

- “In love as in a battle, you have to take a chance.” — Production Notes

- Partenope Plays for Keeps

- Rise of the Avant Garde

- Artists

- Donor Spotlight

- Print Edition

- Plan Your Visit

Partenope

Opera in three acts by George Frideric Handel

To an anonymous libretto

(Sung in Italian with English supertitles)

Cast

(in order of vocal appearance)

Partenope

Julie Fuchs *

Rosmira

Daniela Mack

Arsace

Carlo Vistoli *

Armindo

Nicholas Tamagna *

Ormonte

Hadleigh Adams

Emilio

Alek Shrader

* San Francisco Opera debut † Current Adler Fellow

Creative Team

Conductor

Christopher Moulds

Director

Christopher Alden

Associate Director

Roy Rallo

Set Designer

Andrew Lieberman

Costume Designer

Jon Morrell

Original Lighting Designer

Adam Silverman

Revival Lighting Designer

Gary Marder

Choreographer

Colm Seery

Assistant Conductor

Yang Lin †

Continuo

Christopher Moulds

Peter Walsh

Musical Preparation

Peter Walsh

John Churchwell

Keun-A Lee *

Diction

Alessandra Cattani

Supertitles

Amanda Holden

Assistant Director

E. Reed Fisher

Stage Manager

Jayme O’Hara

Assistant Stage Managers

Collette Berg

Thea Railey

Megan Coutts

Fight Director

Dave Maier

Technical Supervisors

Lawren Gregory

Ryan O’Steen

Costume Supervisor

Galen Till

Hair and Makeup

Jeanna Parham

SATURDAY, JUNE 15, 2024 • 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 19 • 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, JUNE 23 • 2 PM

TUESDAY, JUNE 25 • 7:30 PM

FRIDAY, JUNE 28 • 7:30 PM

TIME AND PLACE: 1920s Paris

ACT I

—INTERMISSION—

ACT II

—INTERMISSION—

ACT III

The performance will last approximately three hours and thirty minutes with two intermissions.

Latecomers may not be seated during the performance after the lights have dimmed.

Patrons who leave during the performance may not be reseated until intermission.

The use of cameras, cell phones, and any kind of recording equipment is strictly forbidden during the performance.

Please turn off and refrain from using all electronic devices.

Synopsis

ACT I

Partenope asks for Apollo’s blessing. Rosmira enters, disguised as a man, and introduces herself as “Eurimene.” Despite the disguise, Arsace recognizes her as his former betrothed. Before they can talk, Ormonte announces that Emilio wants to meet Partenope. Armindo confides in “Eurimene” that he loves Partenope; she, however, is in love with Arsace. Rosmira scolds Arsace for abandoning her; he begs her forgiveness, and she insists that he must not reveal her true identity. Armindo admits to Partenope that he loves her. When “Eurimene” interrupts Partenope and Arsace, “he” declares himself to be yet another of Partenope’s suitors. Partenope continues to assert her devotion to Arsace. Emilio offers Partenope marriage; when she refuses, he threatens her. She asks Arsace to lead her forces against Emilio, and this provokes jealousy among the other suitors. Armindo is perturbed that “Eurimene” is a rival for Partenope, but the disguised Rosmira reassures him that “his” affections lie elsewhere.

ACT II

Partenope’s and Emilio’s forces engage, and Emilio is captured by Arsace. “Eurimene” claims all credit for Emilio’s capture, and Arsace says nothing to the contrary. When Emilio contradicts this assertion, “Eurimene” challenges Arsace to a duel to prove his honor. Arsace attempts to pacify the disguised Rosmira, whose feelings are torn between love and rage. Armindo declares his love for Partenope; she, however, continues to want only Arsace. Alone together, Rosmira and Arsace struggle with conflicting emotions.

ACT III

“Eurimene” tells Partenope that “he” challenged Arsace on behalf of a woman, Rosmira—whom Arsace had promised to marry and then abandoned. When Arsace admits the allegation is true, Partenope rejects him and gives hope to Armindo. Emilio offers Arsace his support in the forthcoming duel. Arsace asks for Rosmira’s forgiveness. When Partenope discovers them together, Rosmira manages to conceal her true identity. Both women scorn Arsace, who rails at the tyranny of love. The contestants are given their weapons for the duel. When Arsace suddenly demands that he and “Eurimene” must fight bare-chested, Rosmira is placed in a dilemma and chooses to reveal her true identity. The lovers change partners: Partenope takes Armindo, and Rosmira and Arsace are reunited.

First performance: London, King’s Theater; February 24, 1730

First performance in the U.S.: Omaha, Nebraska, Opera/Omaha Festival; September 10, 1988

First San Francisco Opera performance: October 15, 2014

Personnel: 6 principals

Orchestra: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 1 bassoon, 3 horns (2 + assistant), 1 trumpet, theorbo, 2 harpsichords, 32 strings

(10 first violins, 8 second violins, 6 violas, 5 cellos, 3 double basses); 44 total

“In love as in a battle, you have to take a chance.”

Production notes by dramaturg Peter Littlefield

Love is dangerous. We all know that. An emotion that is supposed to be about bringing people together, it causes no end of conflict. In Partenope, Handel portrays love as a battle—both literally and figuratively. Prince Emilio attacks the city state of Queen Partenope after she rejects his marriage proposal. And in the various relationships among Partenope; her lover, Arsace; Arsace’s spurned-lover Rosmira; and Armindo, yet another Partenope suitor, the battlefields are many.

Through the character of Rosmira, Handel presents one of love’s mysteries: why does love coexist so easily with hate? (“Tearing at my heart are jealousy, love, and rage in equal portions,” she declares.) And, indeed, she takes her scheme to get Arsace back to an extreme. She enters disguised as a man and competes with him for his position in the court. She embarrasses him in every way she can. And ultimately, she has to question her own relentlessness. Not that Arsace doesn’t enjoy this kind of cat-and-mouse game. It’s what attracts him to her.

Of course, we all become a little crazy in the face of love, because love is the great unsettler. It cares very little about the arrangements people make—the social alliances, the accommodations to power and convention.

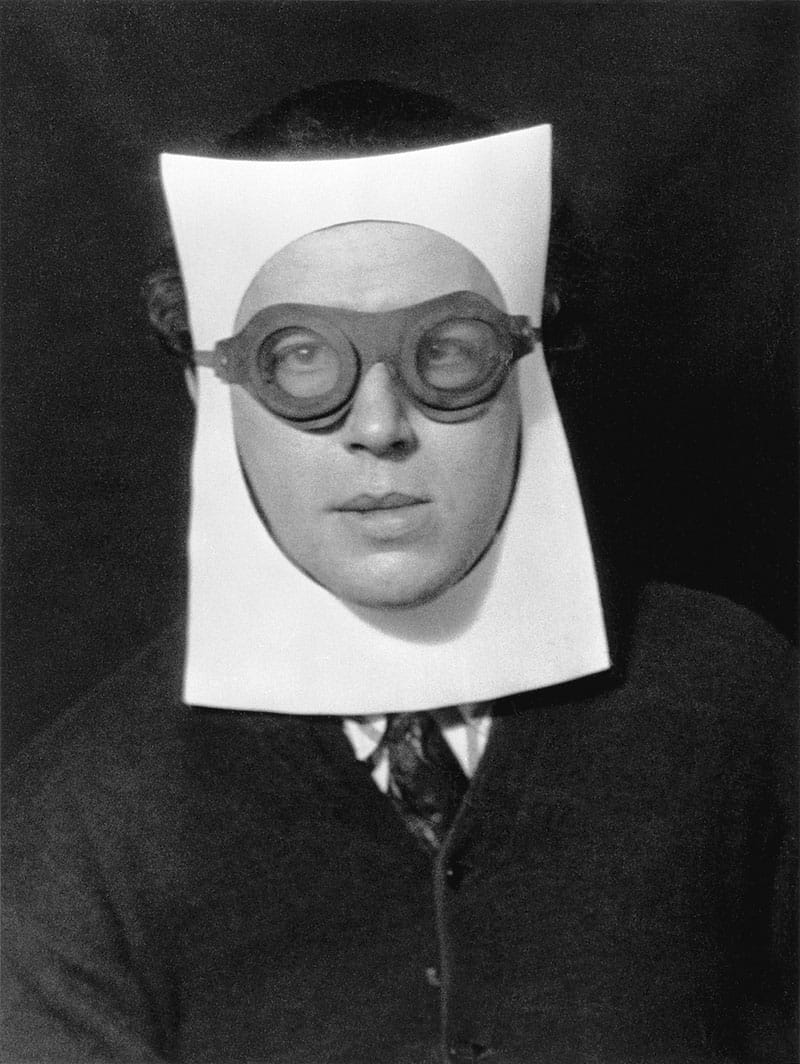

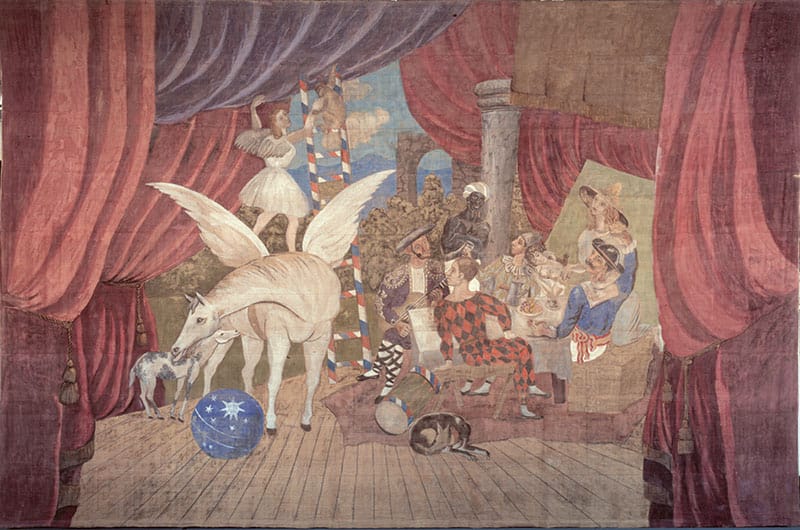

In this production, we took our inspiration from the Surrealists and their vision of the erotic nature of the psyche. Artists and writers such as André Breton, Louis Aragon, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, and Man Ray came of age under the shadow of the First World War. Influenced by the ideas of Freud and wary of industrialization on the one hand and Fascism on the other, they thought the rational ideal of culture was delusional. In their view of the mind, common sense gives way to the logic of dreams. The forces of feeling overturn the artificiality of relationships. And they put desire at the center—elusive, inescapable, and inextricable from love.

We set Partenope’s court in a salon. It’s an elite of socialites, men of affairs and artists who enjoy the daily round of parties, cocktails, and card games. Yet each character is troubled by questions about what these relationships add up to. Each must come to terms with one of love’s difficulties: Partenope struggles with the contradiction between her public role and personal desire, and she has a tendency to pick the wrong kind of man. Arsace evades commitment and is dishonest about his feelings. And Armindo is simply too timid to declare himself. It is left to Ormonte to suggest an approach that seems to elude the others: “In love as in a battle, you have to take a chance.”

The peace of this group is shaken by two assaults. The first, by Rosmira, threatens the relationship between Arsace and Partenope. The second, by Emilio, is more mysterious. We based him very loosely on the Surrealist photographer Man Ray. He uses his camera to uncover the hidden recesses of desire. He is anarchic and mercurial. He is an embodiment of the libido with all its protean qualities, and the attack he launches on this narrow, little group is nothing less than an attack of love. He sets in motion a kind or game in which relationships are transformed.

So Partenope, Arsace, Rosmira, and Armindo fight it out. If love is a battle, as this highly ironic opera suggests, we all have to ask ourselves why. How does it take hold of us, subvert our expectations, and break us down? Therein lies a mystery of humankind, and the answer lies buried in a tangle of feelings. It’s a conundrum expressed in all of our art and literature, and for the Surrealists, it seemed for a moment to hold the key to a revolution of the mind. Love assaults us, they would tell us, with the deeper truth about our natures. And so it would seem for our combatants, whose battle scars are mainly to their illusions.

Stage director and playwright Peter Littlefield was dramaturg for Partenope at the English National Opera.

Photo: Anthony Roth Costanzo (Armindo), Daniela Mack (Rosmira), Danielle de Niese (Partenope), and Philippe Sly (Ormonte) in the final act of Handel’s Partenope.

Partenope Plays for Keeps

By Judith Malafronte

The minute Handel’s London opera company was reorganized in 1729 as the Second Academy of Music, giving him more power, he put Partenope on the schedule and set to work writing it. The previous opera board had rejected his earlier pitches to set this libretto by Silvio Stampiglia, even though it had been around since 1699 and twenty-three different composers had used it. Handel had probably seen Antonio Caldara’s 1708 setting when he was in Venice. Clearly it was a strong piece, but theater agent Owen Swiney had insisted that Partenope would bomb in London. It was “the very worst book (excepting one) that I ever read in my whole life.” He objected in particular to Stampiglia’s attempts at humor and wit, and swore that any success the work might have had in Italy was “from a depravity of Taste in the audience.”

What drew Handel to this libretto? Perhaps it was the same mix of serious and comic elements that Swiney objected to, but that was so characteristic of operas with Venetian ancestry. A libretto penned in 1699 would naturally have reflected the 17th-century aesthetic of high drama mixed with low humor, peppered with contemporary jokes from buffoonish characters. Like Handel’s early Agrippina and the much later Serse, one written for Venice and one set to a Venetian libretto from 1654, Partenope defies genres. Magic and spectacle are entirely absent, along with thorny subplots and absurd last-minute revelations, and Handel eliminated two unneeded jokesters. And, except when Partenope likens her love life to that of a butterfly flitting around a flame (in the beguiling aria “Qual farfalletta”), we find none of those emotionally distancing simile arias where a character claims to feel like a cloud fleeing the wind, a hunter moving steadily and stealthily through the forest, or a rudderless ship in a tempest.(1)

Could it have been the ever so slightly feminist tone of the story that attracted the composer? Partenope’s two female characters blow the men out of the water with their fortitude and complexity. Instead of heroic conflicts between love and duty so common to Handel’s other works, we have “a psychological study of the relations between the sexes seen largely from the woman’s point of view,” in the words of Handel scholar Winton Dean.

As the Queen of Naples, Partenope boasts a collection of suitors and enjoys playing them off against each other. Christopher Alden sees her as a carefree salon hostess, but her music—in major keys with one exception, full of lilting soprano filigree and charm—consistently captivates us. Rosmira, one of Handel’s very best mezzo-soprano roles, is more complex. She’s come in drag to Partenope’s court to track down the man who jilted her. Even when posing as “Eurimene,” behind her determination and inner torments we see the fascinating, passionate, and witty woman Rosmira is destined to be. She is true to Arsace, a shallow cad with a short attention span. First sung by the alto castrato Antonio Bernacchi, an unpopular substitute for the super-star Senesino, Arsace is interested in what’s right in front of him, without the moral decision-making power to regulate his behavior until it’s almost too late. Handel, dramatically astute as always, saves Arsace’s best music for Act Three.

The timid Armindo is hardly a contender, until he develops the nerve—encouraged by “Eurimene”—to declare his love for Partenope. Although Handel’s first Armindo was a female contralto, he used castrati for later revivals of the opera, so a contemporary countertenor makes casting sense. Adding to Partenope’s lineup of lovers is Emilio, an outsider like Rosmira/Eurimene. Rather than insinuating himself into the group by disguise, however, he is confrontational, with assertive music designed for a supremely virtuosic tenor voice. In this production, Alden likens Emilio to famed Surrealist photographer Man Ray, and he is always around, with his camera intruding, capturing, and interpreting the situation. The one character not in pursuit of Partenope is her captain, Oromonte, a bass with a single aria, as in so many other operas of Handel. Here he offers a steadying, philosophical word: “In love, as in battle, you have to take a chance.”

Perhaps Handel was fascinated by the subtly shifting relationships between these characters. Numerous asides highlight the fact that not everyone is on the same page, so it’s important to keep track of who knows what when. Arsace wonders why he is attracted to “Eurimene,” and while it might make him uncomfortable, we are touched. Once she has sworn him to secrecy, Rosmira is able to insult and humiliate Arsace without retaliation, to everyone’s amazement. Poor, timid Armindo, not in on the disguise, is hurt when his friend “Eurimene” starts coming on to Partenope, who he just admitted he loves. Best of all, when Rosmira cheekily challenges Arsace to combat, he says he won’t fight. We know why, but the clueless people onstage respond:

Emilio: What servile Baseness! (Aside)

Armindo: What unmanly Fears! (Aside)

But to the bold Rosmira/Eurimene:

Armindo: What Prodigy of Valour! (Aside)

Emilio: How undaunted! (Aside)

Arsace then bursts into song, but Rosmira beats him to the rhyme:

Arsace: And will that unrelenting Mind,

To stormy Passions all resign’d,

Pursue me with eternal Hate?

Rosmira: (Ah Wretch! Perfidious and ingrate!)

(Aside to him)

Arsace: And can such brooding Vengeance nest

In the soft Mansion of that Breast?

(Rosmira! Oh Rosmira say.) (Aside to her.)

Rosmira: (Oh basely! Skillful to betray.) (Softly.)

Arsace: Oh! Turn on me those lovely Eyes,

And do not all my Prayers despise,

(Rosmira! Oh Rosmira fair!). (Aside to her.)

Rosmira: (Thou faithless Cause of all my Care!) (Aside to him.)(2)

It’s a deliciously witty scene. Rather than contemporary humor based on vulgarity, exaggeration, and sight gags, Partenope’s subtle comedy comes from these skewed perspectives.

Many of the arias in Partenope are short and personal, juicy and real. The characters here, with their feelings so close to the surface, are often unable to present a conventional aria. (And notice how many arias don’t demand the predictable exit.) We should realize from the trite duet they sing (“I die for you / and I for you / dear jewel / beloved”) that Arsace and Partenope are not going to end up together. Certainly, as in opera seria, there are rage arias, soul-searching moments, and internal monologues in the form of accompanied recitatives, but there are also lighter, situational pieces, like Arsace’s first aria:

Either Eurimene is giving off Rosmira’s vibe,

Or Rosmira is pretending to be Eurimene.

The more I contemplate this

The more confused I am.(3)

Rosmira’s disguise gives her access to Partenope’s circle, where she can observe the fickle Arsace and make him squirm. (Similarly, the abandoned Amastre in Handel’s Serse comes to his court dressed as a man, only to learn that he is engaged to another.) Disguise also confers unexpected power. As “Eurimene” Rosmira is able to connect with Armindo, getting him to open up about his feelings for Partenope and eventually act on them.

Shakespeare, of course, made excellent use of gender-swapping, doubly complex with young boys playing female roles. As You Like It’s Rosalinde, disguised as “Ganymede,” safely teaches Orlando how to love her. As “Fidele,” Cymbeline’s Imogen evades a murder attempt, while Portia poses as a young male Clerk of the Law to successfully defend Antonio in The Merchant of Venice. Only Viola, the heroine of Twelfth Night, finds restriction in her male disguise when she falls in love with Orsino, the melancholy duke she is serving as “Cesario,” but is unable to express it openly.

A Shakespearean tone—the gentle tone of his comedies—does color Partenope. And there is a musical tone as well. Verdi often spoke of the tinta of his operas: the orchestral colors and choice of keys that lent each work a specific atmosphere. We might think of Handel’s operas as having a musical quality based on the distribution of vocal parts. The works with mostly treble voices, or those that lack a tenor role, or the operas featuring dueling sopranos have a different feel than Partenope(4). Here there is a richness to the vocal spectrum that brings a welcome variety and naturalness to the various satellites revolving around the sun of Partenope. Stephen Wadsworth, who directed the U.S. premiere in 1988 at Opera Omaha, celebrates the layers of meaning in Partenope: “Some situation comedy scenes play amusingly, for sure, but as with all these operas of Handel, things can go either way. There’s music of incredible emotion, and if you just zoom past it, the piece won’t work. It has to be played for keeps.”

(1) If you are playing “name that tune,” they are Nerone’s “Come nube che fugge dal vento” from Agrippina, Giulio Cesare’s “Va tacito e nascosto,” and too many “Qual nave” arias to name them all, but Cleopatra’s “Da tempeste” will do!

(2) These exchanges, not performed in the current production, appear in the 1730 libretto, with its literary, rhyming, and fleshed out English translation.

(3) My translation

(4) Alessandro, Admeto, Riccardo Primo, Siroe, and Tolomeo

Photo: Danielle de Niese as the title role in the 2014 Company premiere of Handel’s Partenope. / CORY WEAVER

Rise of the Avant Garde

By Judith Malafronte

Looking at the key figures of the Parisian avant garde in the 1920s, it’s startling to realize how many were photographed by Man Ray, the American visual artist at the forefront of the Dadaist and Surrealist movements. It’s fitting then that Christopher Alden uses Ray as a stand in for Emilio, the military commander who uses his camera instead of a sword to probe and explore his environment.

Man Ray, born Emmanuel Radnitzky (1890–1976), arrived in Paris in 1922 and a year later created the influential “Retour à la Raison” (Return to Reason), a three-minute film that uses a camera-less technique where objects are placed directly onto a photographic surface, then exposed to light. The same year he glued a cutout photograph of an eye onto the arm of a wooden metronome and called it “Object to be Destroyed.” (When it was actually destroyed by protesting students in 1957, Ray recreated it and renamed it “Indestructible Object.”) The well-known modified photo “Violon d’Ingres” from 1924 features the back of bohemian cabaret singer and artists’ model Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin), Ray’s lover and muse who had also appeared nude in “Retour à la Raison.”

From centers in Paris and Berlin, avant-garde movements sprang up throughout the early 20th century in every artistic discipline: painting, literature, film, music, dance, theater, photography, fashion, and architecture, with plenty of cross-pollination and collaboration. Manifestos announced each new-ism. In 1909 F. P. Marinetti founded Futurism on the front page of Le Figaro, proclaiming, “we wish to destroy museums, libraries, academies of any sort.” Dadaism used visual, literary, and sound media to elevate nonsense and irrationality, expressed in sound poet Hugo Ball’s 1916 Dada Manifesto. Cubist paintings showed objects from multiple perspectives simultaneously. Surrealism’s psychological dream world pervaded literature, film, music, fashion, and visual arts. Vorticism was primarily an English literary movement, while Expressionism spread from poetry and painting to theater, dance, music, and architecture. Some -isms were publicity stunts, while some had only one follower, like the French poet Albert-Birot who espoused Nunism.

In music, the Neue Wiener Schule composers Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern employed techniques of atonality and Serialism to override tradition. Inspired by Erik Satie’s parody works, the composers of Les Six presented a variety of innovations. Mechanical instruments like the theremin, the ondes martenot, or the Trautonium were invented and were used along with doorbells, typewriters, and airplane propellers. Collaborations between Satie, Picasso, and Cocteau resulted in the Cubist ballet Parade, while Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes brought together composer Stravinsky, choreographer Nijinsky, and designer Roerich for the Fauvist sensation The Rite of Spring.

During this period political upheavals included the Russian Revolution, the Romanian Peasants’ revolt, the Balkan Wars, the Finnish civil war, the Irish War of Independence as well as the rise of Mussolini and the National Fascist Party in Italy, the Nazi Party in Germany, and the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War. Nationalist movements in Catalonia, Scotland, and Belgium gave rise to avant-garde poets who raised issues of geopolitical power and representation. Canadian painters formed a “Group of Seven” in 1920. Estridentismo (Stridentism) arose in Mexico City with an activist agenda. Influenced by avant-garde movements in Berlin, Tomoyoshi Murayama returned to Japan as a modernist artist, writer, and dramatist, spearheading the radical group MAVO and its short-lived magazine. In China, the May Fourth Movement (1919) grew from student protests into a radical cultural wave, with writer Lu Xun encouraging “nalai zhuyi” (Grabism), where Chinese artists would pillage European avant-garde material and transform it into revolutionary, anti-imperialist art, particularly in the form of woodcuts.

While searching for personal artistic freedoms, many avant-garde artists began thinking about gender equality, experimenting with freer dress codes, re-assessing body image, and cross-dressing. The Russian Cubo-Futurist painter Natalia Goncharova wore men’s clothing in public, or—more shockingly—went topless with hieroglyphs and other symbols painted on her torso. Claude Cahun, born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, explored gender ambiguity in her Surrealist writings and photographs and adopted various contradictory public personae in an attempt to avoid restrictive labels.

Like the socialite Partenope in Alden’s staging, many women held salons to cultivate and patronize avant garde artists and writers. Gertrude Stein promoted Matisse, Picasso, and Man Ray, who photographed Stein and Alice B. Toklas in front of their fireplace. Sylvia Beach opened the bookstore Shakespeare and Company, and published James Joyce’s Ulysses. Pacifist and feminist writer Natalie Clifford Barney was openly lesbian and hosted a literary salon for over sixty years. Along with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, Katherine Dreier founded the Société Anonyme and promoted abstract art through exhibitions, concerts, and publications. The journalist and activist Nancy Cunard published experimental writers like Ezra Pound and Samuel Beckett. Might a photograph by Man Ray of Cunard with her famous stack of bangles provide a clue to Partenope’s character?

Photo: Surrealist artists Salvador Dalí (left) and Man Ray (right) photographed by Carl Van Vechten in Paris, 1934. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, WASHINGTON, D.C./BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Artists

Donor Spotlight

John A. & Cynthia Fry Gunn

Once again, the unprecedented generosity of Cynthia and John Gunn has set the stage for a dazzling season at San Francisco Opera. Since 2002, when John joined the Opera Board, the couple has underwritten numerous productions and provided exceptional support for many of the Company’s innovative endeavors. In September 2008, the Gunns made a historic commitment—believed to be the largest gift ever made by individuals to an American opera company—to help fund the signature projects of then General Director David Gockley, including new operas and productions, multimedia projects, and outreach programs, and they have proudly continued that support for General Director Matthew Shilvock. This season, the Gunns’ inspired generosity is helping make possible four productions— Il Trovatore, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, Lohengrin, and The Magic Flute. The Gunns invite everyone to give and join them as a member of San Francisco Opera’s donor community. John comments, “Opera is a dynamic art form, and all of us play a role in keeping it a meaningful part of our social fabric. With you we can propel San Francisco Opera into its next 100 years of artistic history.” John is the former chairman and CEO of Dodge & Cox Investment Managers. He joined the firm in 1972, the year he received his MBA from Stanford Business School and married Cynthia, who graduated from Stanford with an A.B. in political science in 1970. Early in her career, Cynthia was the editor and director of The Portable Stanford book series for 10 years. She edited 28 books by Stanford professors on a vast array of topics, including Economic Policy Beyond the Headlines by George Shultz and Ken Dam. In addition to their support of San Francisco Opera, the Gunns are active members of the community. John is a former trustee of Stanford University and is Chairman Emeritus of the Advisory Board for the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Cynthia currently serves as a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is a former overseer of Stanford’s Hoover Institution, and has been a member of the advisory board of Family and Children Services and the board of the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. Opera lovers are grateful to Cynthia and John and applaud their commitment to keeping San Francisco Opera a leading-edge company.

Bernard and Barbro Osher (Production Sponsor, Partenope)

A native of Maine, Bernard Osher became involved with San Francisco Opera as a subscriber 50 years ago, shortly after moving here from New York. He and his wife Barbro, a native of Sweden, have supported every aspect of the Company’s work, from artist appearances to production facilities. Established in 1977, The Bernard Osher Foundation has funded virtually every major arts organization in the area, including youth programs. Higher education initiatives include scholarships for community college students in California and Maine and for baccalaureate students at universities in every state and the District of Columbia; Osher Lifelong Learning Institutes serving seasoned adults on 123 campuses nationwide; and Osher Centers for Integrative Medicine at six of the nation’s leading medical schools and at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. Bernard is a longstanding member of the Opera’s Board of Directors, serving on the Chairman’s Council. Barbro is Honorary Consul General of Sweden for California and serves as Chairman of the Board of the Osher Foundation.

Denise Littlefield Sobel (Production Sponsor, Partenope)

Denise Littlefield Sobel is a philanthropist with a longstanding commitment to the visual, performing, and supporting arts. She is at the forefront of several initiatives to promote diversity within the arts, including at San Francisco Opera, and serves on numerous diversity committees for other nonprofit organizations. Denise supports a variety of cultural institutions around the world, including the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA, where she is currently the first woman Chair of the Board of Trustees. In 2019, the French government presented Sobel with the country’s highest civilian honor, naming her a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur in recognition of her extraordinary contributions to French culture. In 2023, she was also appointed an Officer of the French Council of the Order of Arts and Letters. The youngest child of Edmund Wattis Littlefield and Jeannik Méquet Littlefield, she continues her parents’ legacy of support of San Francisco Opera through her personal philanthropy and the Edmund W. and Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Endowment Fund, which provides a permanent and unrestricted source of income for the Company. In 2021, she and her brother, Ed Littlefield, Jr., received the Crescendo Award, bestowed by the San Francisco Opera Guild, for their family’s half-century support of San Francisco Opera.

Print Edition

Plan Your Visit

Visit SFOpera.com for more information on the following topics

New to opera? First things first, welcome! Second, feel free to skim our short list of good-to-knows before joining us.