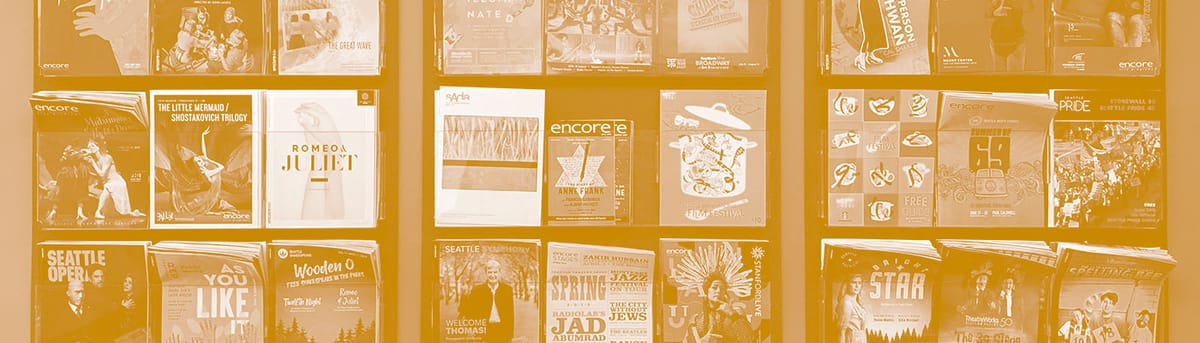

May 30–June 30, 2024

In This Program

- About the Show

- Synopsis

- The Magic Flute: A Magical Storybook

- Shadows and Light: The Magic Flute in the Golden Twenties

- The Magic Flute Creative Showcase

- Donor Spotlight

- Print Edition

- Plan Your Visit

The Magic Flute

Die Zauberflöte

Opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder

(Sung in German with English supertitles)

Cast

(in order of vocal appearance)

Tamino

Amitai Pati

First Lady

Olivia Smith †

Second Lady

Ashley Dixon

Third Lady

Maire Therese Carmack *

Papageno

Lauri Vasar *

The Queen of The Night

Anna Simińska *

Monostatos

Zhengyi Bai

Pamina

Christina Gansch

First Spirit

Niko Min *

Second Spirit

Solah Malik *

Third Spirit

Jacob A. Rainow *

The Speaker (The Old Priest)

Jongwon Han †

Sarastro

Kwangchul Youn *

Papagena

Arianna Rodriguez †

First Armored Man

Thomas Kinch *†

Second Armored Man

James McCarthy *†

Chorus

* San Francisco Opera debut

† Current Adler Fellow

TIME AND PLACE: A Fairy-Tale World

ACT I

—INTERMISSION—

ACT II

Creative Team

Conductor

Eun Sun Kim

Production

Barrie Kosky * and Suzanne Andrade *

Revival Stage Director

Tobias Ribitzki *

Production Designer

Esther Bialas *

Animation Designer

Paul Barritt *

Chorus Director

John Keene

Assistant Conductor

Robert Mollicone

Prompter

Andrew King

Fortepiano

Bryndon Hassman

Musical Preparation

Bin Yu Sanford

Bryndon Hassman

Julian Grabarek *†

John Churchwell

Fabrizio Corona

Diction

Anja Burmeister

Supertitles

Komische Oper Berlin

Assistant Director

Morgan Robinson

Stage Manager

Thea Railey

Animation Stage Manager

Jennifer Harber

Assistant Stage Managers

Collette Berg

Anna Reetz

Jonathan S. Campbell

Dance Master

Colm Seery

Fight Director

Dave Maier

Technical Supervisors

Scott Cavallo

Ryan O’Steen

Costume Supervisor

Jai Alltizer

Hair and Makeup

Jeanna Parham

THURSDAY, MAY 30, 2024 • 7:30 pm

SUNDAY, JUNE 2 • 2 pm

TUESDAY, JUNE 4 • 7:30 pm

SATURDAY, JUNE 8 • 7:30 pm

FRIDAY, JUNE 14 • 7:30 pm

THURSDAY, JUNE 20 • 7:30 pm

SATURDAY, JUNE 22 • 7:30 pm

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 26 • 7:30 pm

SUNDAY, JUNE 30 • 2 pm

The performance will last approximately two hours and fifty minutes with one intermission.

Latecomers may not be seated during the performance after the lights have dimmed.

Patrons who leave during the performance may not be reseated until intermission.

The use of cameras, cell phones, and any kind of recording equipment is strictly forbidden.

Please turn off and refrain from using all electronic devices.

Synopsis

The Magic Flute

ACT I

In a dark forest, far away …

As he flees from a dangerous giant serpent, Tamino is rescued at the last second by the three ladies who serve the Queen of the Night. When he regains consciousness, the first thing Tamino sees is Papageno, and he believes him to be his rescuer.

Papageno, a bird catcher in search of love, does nothing to dispel the misunderstanding. The three ladies return and punish Papageno for his lies by rendering him mute. They show Tamino a picture of Pamina, the daughter of the Queen of the Night, with whom Tamino instantly falls in love.

Shortly thereafter, the Queen of the Night herself appears and tells Tamino of her daughter’s kidnapping at the hands of Sarastro. Tamino responds with great enthusiasm to her command that he free Pamina. The three ladies give Papageno back his voice and instruct him to accompany Tamino. As a protection against danger, they give Tamino the gift of a magic flute, while Papageno receives magic bells. The three ladies declare that three boys will show Tamino and Papageno the way to Sarastro.

Pamina is being importuned by Sarastro’s slave Monostatos. Papageno, who has become separated from Tamino on the way to Sarastro, is as scared by the strange appearance of Monostatos as Monastatos is by Papageno’s. Alone with Pamina, Papageno announces that her rescuer Tamino will soon arrive. Papageno himself is sad that his search for love has thus far proved fruitless. Pamina comforts him.

The three boys have led Tamino to the gates of Sarastro’s domain. Although he is initially refused entry, Tamino begins to doubt the statements regarding Sarastro made by the Queen of the Night. He begins to play his magic flute and enchants nature with his music.

Papageno meanwhile flees with Pamina, but they are caught by Monostatos and his helpers. Papageno’s magic bells put their pursuers out of action. Sarastro and his retinue then enter upon the scene. Monostatos leads in Tamino. The long yearned-for encounter between Tamino and Pamina is all too brief. Sarastro orders that they must first face a series of trials.

ACT II

The trial of silence

Tamino and Papageno must practice being silent. Because of the appearance of the ladies and their warnings, their ordeal is a truly testing one. Tamino remains resolute, while Papageno immediately begins to chatter.

Meanwhile, Monostatos again tries to get close to the sleeping Pamina. The Queen of the Night appears and orders her daughter to kill Sarastro. Pamina remains behind, despairing. Sarastro seeks to console Pamina by foreswearing any thoughts of revenge.

The trial of temptation

Tamino and Papageno must resist any temptation: no conversation, no women, no food! As well as the magic flute and magic bells the three boys also bring Tamino and Papageno food, which Tamino once again steadfastly resists. Even Pamina fails to draw a single word from Tamino’s lips, which she interprets as a rejection. She laments the cooling of Tamino’s love for her. Before the last great trial, Pamina and Tamino are brought together one last time to say farewell to one another.

Papageno is not permitted to take part in any further trials. He now wishes for only a glass of wine and dreams of love. For her part, Pamina believes that she has lost Tamino forever. In her despair, she seeks to end her own life but is prevented from doing so by the three boys, who assure her that Tamino still loves her. Gladdened and relieved, Pamina accepts their invitation to see Tamino again. Reunited at last, Tamino and Pamina undergo the final trial together.

The trial of fire and water

The music of the magic flute and their love for one another allow Tamino and Pamina to conquer their own fear and overcome the dangers of fire and water.

Papageno is meanwhile still unsuccessful in his search for love. Despairing, he now also seeks to end his life but is also prevented from doing so by the three boys. Papageno’s dream finally comes true: together with his Papagena, they dream of being blessed with many children.

Meanwhile … the Queen of the Night, the three ladies, and the turncoat Monostatos arm themselves for an attack against Sarastro and his retinue. However, the attack is repelled. Tamino and Pamina have completed their trials and can finally be together.

First performance: Vienna, Theater auf der Wieden, September 30, 1791

First performance in the U.S.: New York, Palmo’s Opera House, April 17, 1833

First San Francisco Opera performance: October 11, 1950

Personnel: 16 principals, 42 choristers, 4 supernumeraries;

62 total

Orchestra: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (both doubling basset horns), 2 bassoons, 3 horns,

2 rotary trumpets, 3 trombones, 1 timpani,

2 percussion, keyboard glockenspiel, 32 strings (10 first violins, 8 second violins, 6 violas, 5 cellos, 3 double basses); 52 total

The Magic Flute: A Magical Storybook

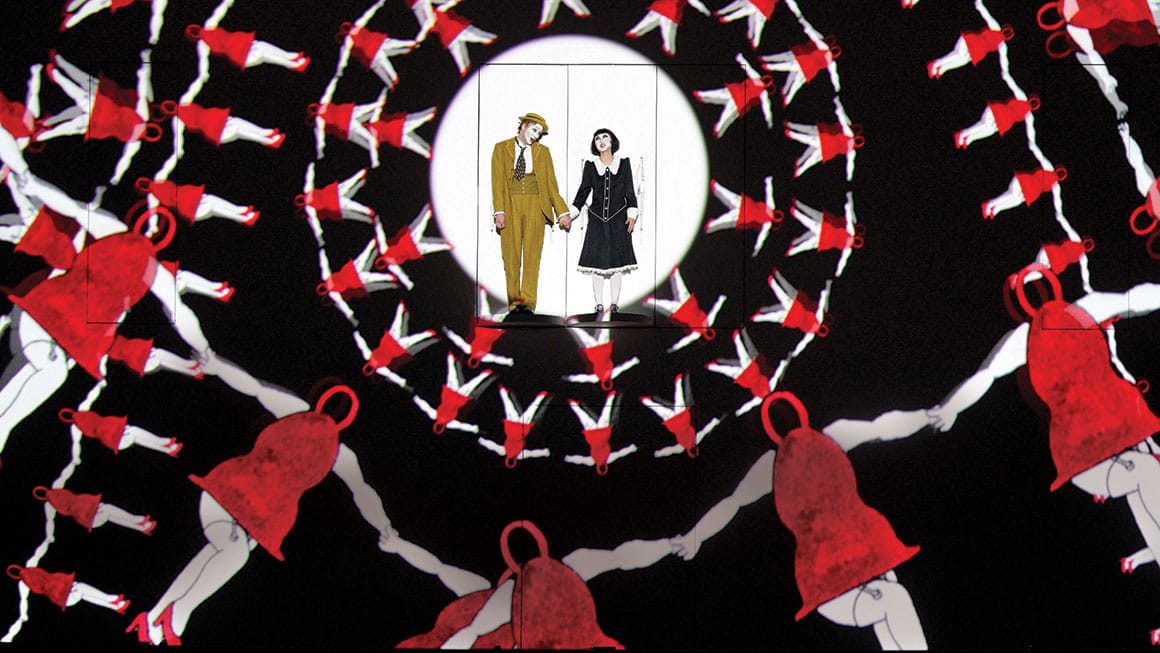

Barrie Kosky, Suzanne Andrade, and Paul Barritt on flying elephants, the world of silent film, and the eternal search for love

How did you come up with the idea of staging The Magic Flute with the British theater company 1927?

Barrie Kosky (stage director): The Magic Flute is the most frequently performed German-language opera, one of the top 10 operas in the world. Everyone knows the story; everyone knows the music; everyone knows the characters. On top of that, it is an “ageless” opera, meaning that an eight-year-old can enjoy it as much as an octogenarian can. So you start out with some pressure when you undertake a staging of this opera. I think the challenge is to embrace the heterogeneous nature of this opera. Any attempt to interpret the piece in only one way is bound to fail. You almost have to celebrate the contradictions and inconsistencies of the plot and the characters, as well as the mix of fantasy, surrealism, magic, and deeply touching human emotions.

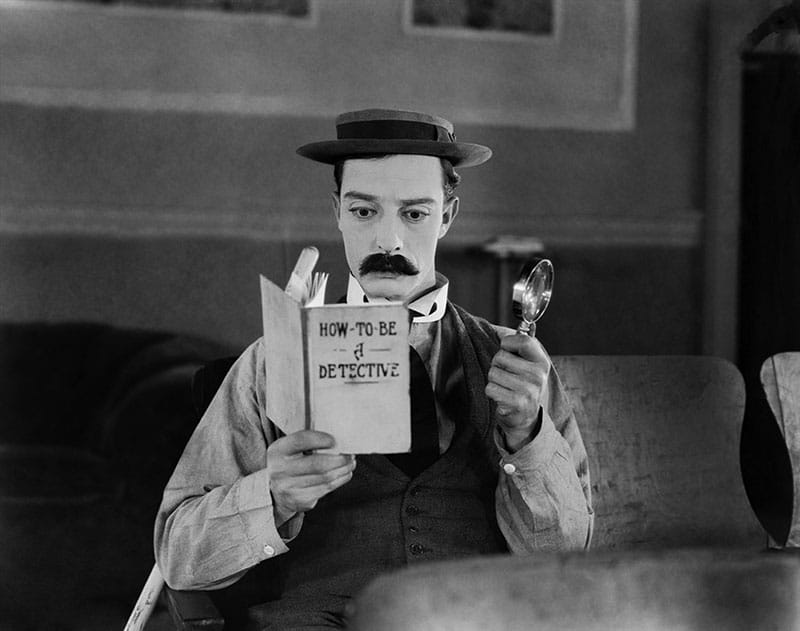

About 13 years ago I attended a performance of Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, the first show created by the British theater company known as 1927. From the moment the show started, there was this fascinating mix of live performance with animations, creating its own aesthetic world. Within minutes, this strange mixture of silent film and music hall had convinced me that these people had to do The Magic Flute with me in Berlin! It seemed to me quite an advantage that Paul and Suzanne would be venturing into opera for the first time. because they were completely free of any preconceptions about it, unlike me.

The result was a unique The Magic Flute.

Although Suzanne and Paul were working in Berlin for the first time, they had a natural feel for the city’s artistic ambiance, especially the Berlin of the 1920s, when it was such an important creative center for painting, cabaret. silent film, and animated film. Suzanne, Paul, and I share a love for revue, vaudeville, music hall, and similar forms of theater, and, of course, for silent film. So our Papageno is suggestive of Buster Keaton, Monostatos is a bit Nosferatu, and Pamina perhaps a bit reminiscent of Louise Brooks. But it’s more than an homage to silent film, there are far too many influences from other areas. But the world of silent film gives us a certain vocabulary that we can use in any way we like.

Is your love of silent film the motivation behind the name 1927?

Suzanne Andrade (stage director/writer/performer; co-creator of 1927): 1927 was the year of the first sound film: The Jazz Singer with Al Jolson, an absolute sensation at the time. Curiously, however, no one believed at that time that the talkies would prevail over silent films. We found this aspect especially exciting. We work with a mixture of live performance and animation, which makes it a completely new art form in many ways. Many others have used film in theater, but 1927 integrates film in a very new way. We don’t do a theater piece with added movies. Nor do we make a movie and then combine it with acting elements. Everything goes hand in hand. Our shows evoke the world of dreams and nightmares, with aesthetics that hearken back to the world of silent film.

Paul Barritt (filmmaker; co-creator of 1927): And yet it would be wrong to see in our work only the influence of the 1920s and silent film. We take our visual inspiration from many eras, from the copper engravings of the eighteenth century as well as in comics of today. There is no preconceived aesthetic setting in our mind when we work on a show. The important thing is that the image fits. A good example is Papageno’s aria “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” [a girl or a little wife]. In the libretto, he is served a glass of wine in the dialogue before his aria, “We let him have a drink,” but it isn’t wine. It’s a pink cocktail from a giant cocktail glass, and Suzanne had the idea that he would start to see pink elephants flying around him. Of course, the most famous of all flying elephants was Dumbo—from the 1940s—but the actual year isn’t important as long as everything comes together visually.

SA: Our Magic Flute is a journey through different worlds of fantasy. But as in all of our shows, there is a connecting style that ensures that the whole thing doesn’t fall apart aesthetically.

BK: This is also helped by 1927’s very special feeling for rhythm. The rhythm of the music and the text has an enormous influence on the animation. As we worked together on The Magic Flute, the timing always came from the music, even—especially—in the dialogues, which we condensed and transformed into silent film intertitles with piano accompaniment.

However, we use an eighteenth-century fortepiano, and the accompanying music is by Mozart, from his two fantasias for piano, K.475 in C minor and K.397 in D minor. This not only gives the whole piece a consistent style but also a consistent rhythm. It’s a silent film by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, so to speak!

Does this piece work without the dialogue?

SA: I think that almost any story can be told without words. You can undress a story to the bone, to find out what you really need to convey the plot. We tried to do that in The Magic Flute. You can convey so much of a story through purely visual means. You don’t always need two pages of dialogue to show the relationship between two people. You don’t need a comic dialogue to show that Papageno is a funny character. A clever gimmick can sometimes offer more insight than dialogue.

PB: Going back to silent films, for a moment—they weren’t just films without sound, with intertitles in place of the missing voices. lntertitles were actually used very sparingly. The makers of silent films instead told their stories through the visual elements. While talkies convey the stories primarily through dialogue, silent films told their story through gestures, movements, and glances, and so on.

BK: This emphasis on the images makes it possible for every viewer to experience the show in his or her own way: as a magical, living storybook; as a curious, contemporary meditation on silent film; as a singing silent film; or as paintings come to life. Basically, we have a hundred stage sets in which things happen that normally aren’t possible onstage: flying elephants, flutes trailing notes, bells as showgirls … . We can fly up to the stars and then ride an elevator to hell, all within a few minutes. In addition to all the animation in our production, there are also moments when the singers are in a simple white spotlight and suddenly there’s only the music, the text, and the character. The very simplicity makes these perhaps the most touching moments of the evening. During the performance, the technology doesn’t play in the foreground. Although Paul spent hours and hours sitting in front of a computer to create it, his animation never loses its deeply human component. You can always see that a human hand has drawn everything. Video projections as part of theatrical productions aren’t new. But they often become boring after a few minutes, because there isn’t any interaction between the two-dimensional space of the screen and the three dimensions of the actors. Suzanne and Paul have solved this problem by combining all of these dimensions into a common theatrical language.

What is The Magic Flute really about?

PB: It’s a love story, told as a fairy tale.

SA: The love story between Tamino and Pamina. Throughout the entire piece, the two try to find each other—but everyone else separates them and pulls them away from each other. Only at the very end do they come together.

BK: A strange, fairy-tale love story, one that has a lot of archetypal and mythological elements, such as the trials they must undergo to gain wisdom. They have to go through fire and water to mature. These are ancient rites of initiation. The Masonic trappings imposed on the story interested us very little, since they have, of course, much, much deeper roots.

Tamino falls in love with a portrait. How many myths and fairy tales include this plot point? The hero falls in love with a picture and goes in search of the subject. And on his way to her, he encounters all sorts of obstacles. And, at the same time, the object of his desire faces her own personal obstacles on her own journey.

You can experience our production as a journey through the dream worlds of Tamino and Pamina. These two dream worlds collide and combine to form one strange dream. The person who combines these dreams and these worlds is Papageno. We are very focused on these three characters. Interestingly, Papageno is in pursuit of an idealized image too: the perfect fantasy woman at his side, something he craves almost desperately. Despite all of the comedic elements, there is a deep loneliness in The Magic Flute. Half of the piece is the fact that people are alone—despite the joy in Papageno’s birdcatcher aria, it’s ultimately about a man who feels lonely and longs for love. At the beginning of the opera, Tamino is running alone through the forest. The three ladies are alone, so they are immediately attracted to Tamino. The Queen of the Night is alone—her husband has died and her daughter has been kidnapped. Even Sarastro, who has a large following, has no partner at his side. Not to mention Monostatos, whose unfulfilled longing for love degenerates into unbridled lust. The Magic Flute is about the search for love and about the different forms that this search can take.

Finally, it is also an Orphic story—it is about the power of music, music that can move mountains and nature. After all, the opera is called The Magic Flute not Tamino and Pamina! The magic flute isn’t just an instrument, it is the quintessence of music, and music in this case, is synonymous with love. I think that’s the reason why so many people love this opera so much, because they see, hear, and feel that it’s a universal representation of those looking for love, a journey that we all take time and time again.

This interview by Ulrich Lenz originally appeared in the LA Opera program book and is reprinted by permission.

Photos: Cory Weaver/Lyric Opera of Chicago

Shadows and Light: The Magic Flute in the Golden Twenties

By Alexandra Monchick

Imagine the golden twenties at night. Under neon lights in dark streets, one finds inside identical cropped-haired cabaret girls in scanty, fringed costumes. The room is cloaked in smoke as an infinite fountain of cocktails backs the energy of the crowd. Policemen in rounded hats tap their feet to the Charleston as they lean back and ogle the legs of women dancing in a mechanistic chorus line. How could one set The Magic Flute, a family-friendly fairy tale, during this era of salaciousness that precedes one of the darkest periods in modern world history?

Director Barrie Kosky and the British theater company 1927 have crafted a Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”) of music, staging, and animation to revivify and shed a not-so-metaphorical new light on one of the most performed operas in the world. At first glance, an incongruous connection appears in the linking of The Magic Flute with 1920s Germany. We know we are in this era of the Weimar Republic because of silent film character prototypes, silhouette projections, and glowing animation. This time reflects the crisis of modernity just as Mozart’s last opera embodied the crisis of Enlightenment.

Many historical comparisons can be drawn between 1791, the year Mozart composed The Magic Flute, and 1927, a hypothetical year in which this production takes place. Having died two months after his opera’s premiere and only two years after the storming of the Bastille, Mozart would not witness the Reign of Terror or Napoleon’s subsequent rise to power. Yet, Mozart was steeped in tenets of knowledge, logic, and equality which sparked the revolution and its reverberations throughout Europe. It was an era of democratic optimism not unlike the founding of the Weimar Republic. Established as the outcome of the November Revolution in 1918, which ultimately ended the First World War and German monarchy, the new republic rekindled enlightenment ideals, albeit during a fraught era of political and economic instability.

The zeitgeist of both periods provoked corresponding artistic trends and responses. In the late eighteenth century, the literary, artistic, and musical movement of Sturm und Drang (“storm and stress”) was overthrown by Weimar Classicism. It was no coincidence that the Weimar Constitution was signed in 1918 in the city of Goethe, Herder, and Schiller. Weimar, the small Thuringian city southwest of Berlin, was chosen over similarly sized cities due to its Enlightenment history. With its topics of anguish, gloom, and despair, a movement analogous to Sturm und Drang, German Expressionism arose during the early twentieth century and became especially popular during the early 1920s. In film, Expressionist themes were depicted by deep angles, camera tilting, and contrasts in shadows and light to the extent that shadows were sometimes painted on the sets. Likewise, Expressionism in music was depicted by angular melodic gestures, a high level of dissonance, and extreme dynamic and textural contrasts.

By the latter part of the decade, the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) began to supersede Expressionism as a countermovement. Rather than exaggerating and distorting reality, works of the Neue Sachlichkeit aimed to reflect the harshness of reality with authentic sets and straightforward camera work. In the fast-moving montages of the New Objectivity, the film editor became as important as the director and actors. A more nebulous concept in music, Neue Sachlichkeit generally denotes simplicity and accessibility with the implementation of clearly defined neo-classical forms, as well as stylized dances or jazz numbers.

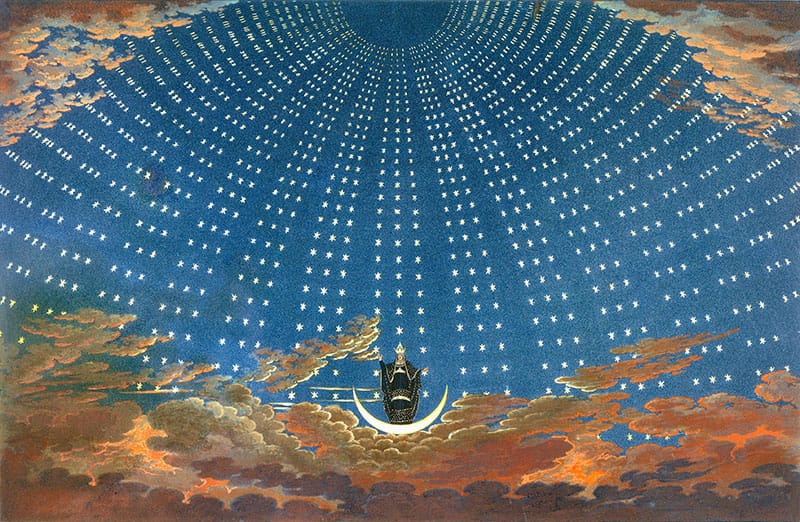

Even without advanced stage design and animation, the story of The Magic Flute lends itself easily to being set in the Weimar Republic. It is replete with static characters and binary juxtapositions: good and evil, piety and irreverence, honesty and deceit, and hysteria and control, all of which are portrayed with the textural and musical images of darkness and light. If we take the most famous aria from this opera, The Queen of the Night’s “Der Hölle Rache,” the low d-minor tremolos meandering to deceptive keys through tertiary motion evokes the musical topos of Sturm und Drang, the antithesis to balanced rationalism. Many of the queen’s vocal stylings are in the tempesta style, a popular idiom to represent storms during Mozart’s time. The trope of thunder and lightning recurs in the opera, and it is a gargantuan storm that ultimately brings down the Queen and her entourage. The frenetic, melismatic (many notes per syllable), athletic coloratura style in which she sings is evocative of an earlier late Baroque time. Her vocality competes to overthrow the wisdom of Sarastro, which is depicted musically in the chorus “O Isis und Osiris,” his balanced, stable phrases spanning a range of only a tenth. The accompanying horns and regal chorus evoke a sense of royal authority that is achieved not through power but wisdom. By contrast, Papageno, the consummate id in the opera, sings in a simple folklike pastorale style, representing his primal quest for one thing: a woman with whom to procreate. Tamino and Pamina are the most dynamic characters in the opera, having gone through their own enlightenment. Their arias move between the worlds of Papageno and Sarastro with their simple but virtuosic melodies spanning wider ranges.

This production of The Magic Flute invokes Weimar-era film and theater with its Expressionist sets and famous film characters of the late silent era. The spoken dialogue in Schikaneder’s libretto—the German equivalent to the dry recitative of contemporary Italian opera—is displayed on stage as film intertitles, captions broadcast on the screen during the silent era to express dialogue or to provide additional descriptive or narrative nuance that the characters’ pantomime cannot convey.

Some characters in the Kosky and Andrade production of The Magic Flute share an affinity with stars of the silent film era such as Max Shreck (Nosferatu, 1922); Louise Brooks (Pandora’s Box, 1929, with Alice Roberts as Geschwitz, Brooks as Lulu, Fritz Kortner as Dr. Schön); and Buster Keaton (Sherlock Jr., 1924). / ALAMY STOCK PHOTOS

The duo 1927 takes its name from the year that signaled the beginning of the end of the silent film era. And while a prosperous year for the global film industry, it also marked the decline of the golden age of cinema in Germany, where sound film caught on more slowly. While Hollywood receives most of the credit for the early film industry–its ultimate achievement being the 1927 release of the first talkie, The Jazz Singer–the German film industry was equally prosperous during the silent era. Located in Babelsberg, just over 20 miles from central Berlin, many seminal films were produced there in the 1920s. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, also released in 1927, was one of the first feature-length science fiction films. Babelsberg created suspense shadows, camera angles, and pacing in Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and M, thus forging the genre of modern-day horror films. Not known for their own comedy, Germans became enamored with American slapstick comedy, especially Charlie Chaplin. The first surviving feature-length animation film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed, a fantastical presentation of Arabian nights, had its German premiere in 1926.

Characters share an affinity with several silent film characters and the animation references both popular and more obscure silent film plot references. Kosky points out that Pamina could be seen as Louise Brooks, Papageno as Buster Keaton, and Monostatos as Nosferatu. Tamino also looks remarkably like a hatless Charlie Chaplin, Papagena like Marlene Dietrich, and the Queen of the Night like Christine of Die schwarze Spinne, a 1921 horror film based on the Swiss novel of the same name. In a simple tale of good and evil, the Faustian antiheroine emits a plague of poisonous spiders from her face killing the cattle of the village. When the Queen of the Night casts a swarm of animated spiders around Pamina, this lesser-known silent film is invoked.

The backdrop of the stage could be an Expressionist silent film set where characters appear and fade through backlighting. The characters’ exaggerated silent film gestures and the vivid animation in the production highlight pictorialism over melodrama and point to issues opera directors were grappling with in the 1920s. The craft of acting in opera triggered some debate during the silent film age. Both opera and silent film convey emotion through mimesis, yet gestures and expressions are minimized on the stage and magnified on the screen through closeups.

Despite the perception of an operatic crisis, the 1920s were some of the most fruitful years in German-language opera. Zeitoper, or topical opera, was a popular genre that appealed to the mass public. The genre is closely associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit with its topical themes, contemporary sets, and popular music. The libretti, often containing elements of farce and irony, are set in the present. Characters are typically everyday people rather than heroes, mythological figures, or royalty; sometimes they are even presented as recognizable modern stereotypes. They speak on the phone, play records, take pictures, drive cars, and shoot movies. The action takes place in locales considered either modern or commonplace, such as office buildings, train stations, and living rooms. Sets were cutting-edge at the time, often employing split staging, state-of-the-art lighting design, and film projections.

Zeitopern were performed in small opera houses across Germany, particularly the industrial northern Rhein region. By contrast the Berlin Kroll Oper, directed by Otto Klemperer from 1927–33, was known for updating well-known works such as Fidelio, Der Freischütz, and The Magic Flute, with avant-garde staging and technology. Many of the sets resembled the cubist animation of the era that was popular in film commercials for liquor, phonographs, car tires, and other household goods. The commercials were shown in color, which was a shocking contrast from the films of the era. Kosky’s staging is reminiscent of a Kroll 1920s production, and the colorful animation and lighting against the backdrop of monochromatic sets evoke a similar juxtaposition of images the 1920s moviegoer would have seen.

Whereas some operas and operatic productions embed film, sometimes even with the actors on stage as in Kurt Weill’s Royal Palace or Alban Berg’s Lulu, this production of The Magic Flute uses simultaneous animation. With 736 animation cues, synchronization is a challenge in the production. Actors must learn to block and move precisely with musical cues down to the eighth note so that they align with the animations. At the same time the stage manager cues the projections following the score. Such synchronization challenges with images and music were similar during the silent era. Thus, for a short period, composers aimed to write mechanical accompaniments rather than rely on a film orchestra or keyboard accompanist. Paul Hindemith and Hans Eisler, for example, wrote mechanical keyboard accompaniments to cartoons for the first Baden-Baden music festival as they felt the automatic pacing of a mechanical organ would best compliment the fixed rolling image of an animated short.

There is no dialogue in this Magic Flute, as is typical in German Singspiel, a type of German-language music theater during Mozart’s time. Unlike in Italian opera where the dialogue is transmitted through in recitativo secco (a sung free rhythm), the dialogue in the Singspiel is spoken. Arias and choruses are vehicles for emotional expression, whereas dialogue, whether sung or spoken, advances the plot. The team behind this production omitted dialogue, instead placing it on intertitles as in a silent film. This makes the opera purely musical and continuous like a flickering film reel.

We could imagine this The Magic Flute as not only an homage to silent film but as an exploration of enlightenment representing both The Age of Reason and as an educational process. It is a Zeitoper of its own time. In one scene in the production, the words Wahrheit, Weisheit, Arbeit, Kunst, Tugend [truth, wisdom, work, art, virtue] appear with a giant mechanical head reminiscent of the Maschinenmensch from Metropolis, displaying the morals and values of Mozart’s and Fritz Lang’s societies. In his 1927 essay “The Mass Ornament,” a critique of mass culture and commentary on the so-called crisis of modernity, the famous Weimar film critic Siegfried Kracauer writes, “Reason does not operate within the circle of natural life. Its concern is to introduce truth into the world. Its realm has already been intimated in genuine fairy tales, which are not stories about miracles but rather announcements of the miraculous advent of justice. … Natural power is defeated by the powerlessness of the good; fidelity triumphs over the arts of sorcery.” Kracauer could just have easily been writing about The Magic Flute.

Alexandra Monchick is a musicologist based in Los Angeles and has written extensively about music during the Weimar Republic.

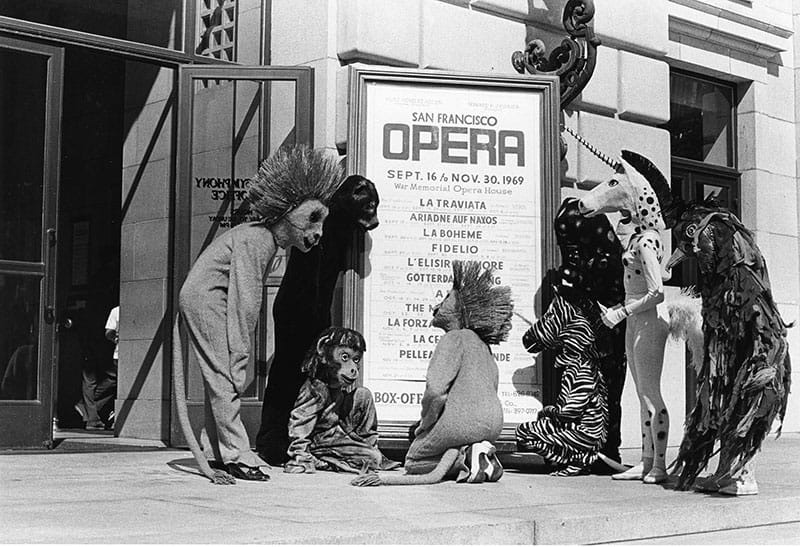

The Magic Flute Creative Showcase

THROUGH THE YEARS

With its fairy-tale story and fantastical characters, The Magic Flute has long drawn creatives to the challenge of realizing its ideal representation on the stage. This season, Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade’s production, with designs by Esther Bialas and animation by Paul Barritt, joins San Francisco Opera’s tradition (dating back to the 1950 Company premiere) for presenting Mozart’s masterpiece with imagination, verve, and joy. Below are a few snapshots, including the work of iconic artists Marc Chagall, David Hockney, and Jun Kaneko.

First: Act I scene for the Queen of the Night in 1967 by Company resident designer Davis L. West. / CAROLYN MASON JONES Second: Zdzislawa Donat in her 1975 American debut as the Queen of the Night, designed by Toni Businger. / GREG PETERSON Third: Sally Wolf as the Queen of the Night in the 1990 revival of the David Hockney production. / ROBERT CAHEN

First: Marc Chagall’s iconic production arrived in 1980 with Barbara Carter as the Queen of the Night. / RON SCHERL Second: Albina Shagimuratova as the Queen of the Night in the production designed by Jun Kaneko, 2012. / CORY WEAVER Third: The opera’s finale in 1975, designed by Businger and West, featuring Margaret Price (Pamina), David Ward (Sarastro), and Stuart Burrows (Tamino). / ROBERT CAHEN

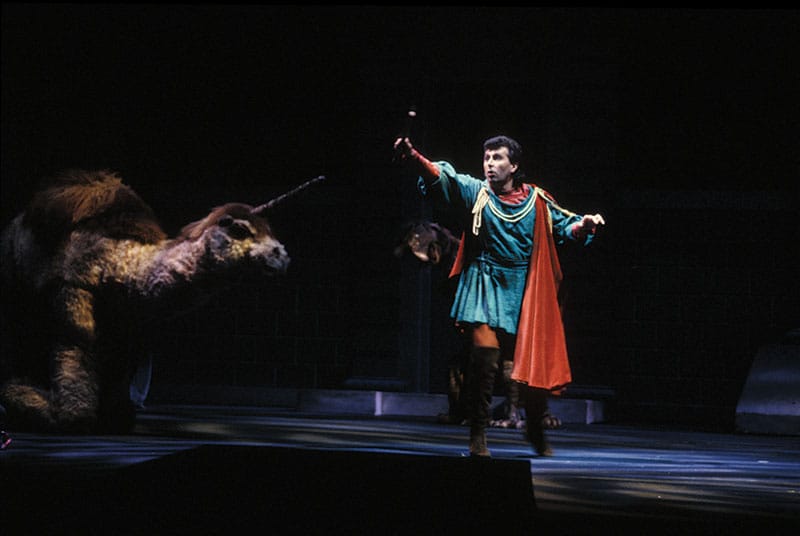

First: Paul Appleby as Tamino charms the animals designed by Jun Kaneko in 2015. / CORY WEAVER Second: The animals from The Magic Flute read about the Company’s 1969 season outside the Opera House. / MARGARET NORTON Third: The animals are serenaded by the Tamino of Jerry Hadley in the Hockney production, 1990. / ROBERT CAHEN

First: The Three Ladies (Renée Tatum, Lauren McNeese, Melody Moore) defend Tamino (Alek Shrader) from the serpent in the Kaneko production, 2012. / CORY WEAVER Second: Barbara Lauppe, Yvonne Chauveau, and Claramae Turner as the Three Ladies in the 1950 Company premiere. / STROHMEYER Third: Shigemi Matsumoto as Papagena and Geraint Evans as Papageno in the 1969 production, designed by Businger and Davis. / ROBERT CAHEN

Artists

Donor Spotlight

John A. & Cynthia Fry Gunn

Once again, the unprecedented generosity of Cynthia and John Gunn has set the stage for a dazzling season at San Francisco Opera. Since 2002, when John joined the Opera Board, the couple has underwritten numerous productions and provided exceptional support for many of the Company’s innovative endeavors. In September 2008, the Gunns made a historic commitment—believed to be the largest gift ever made by individuals to an American opera company—to help fund the signature projects of then General Director David Gockley, including new operas and productions, multimedia projects, and outreach programs, and they have proudly continued that support for General Director Matthew Shilvock. This season, the Gunns’ inspired generosity is helping make possible four productions— Il Trovatore, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, Lohengrin, and The Magic Flute. The Gunns invite everyone to give and join them as a member of San Francisco Opera’s donor community. John comments, “Opera is a dynamic art form, and all of us play a role in keeping it a meaningful part of our social fabric. With you we can propel San Francisco Opera into its next 100 years of artistic history.” John is the former chairman and CEO of Dodge & Cox Investment Managers. He joined the firm in 1972, the year he received his MBA from Stanford Business School and married Cynthia, who graduated from Stanford with an A.B. in political science in 1970. Early in her career, Cynthia was the editor and director of The Portable Stanford book series for 10 years. She edited 28 books by Stanford professors on a vast array of topics, including Economic Policy Beyond the Headlines by George Shultz and Ken Dam. In addition to their support of San Francisco Opera, the Gunns are active members of the community. John is a former trustee of Stanford University and is Chairman Emeritus of the Advisory Board for the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Cynthia currently serves as a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is a former overseer of Stanford’s Hoover Institution, and has been a member of the advisory board of Family and Children Services and the board of the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. Opera lovers are grateful to Cynthia and John and applaud their commitment to keeping San Francisco Opera a leading-edge company.

Jan Shrem & Maria Manetti Shrem (Production Sponsor, The Magic Flute)

Jan and Maria both developed a love of opera at a young age, although they grew up half-a-world apart.

Jan Shrem, after a career devoted to his publishing businesses in Japan and Europe, created Clos Pegase Winery in California’s Napa Valley, collecting some of the world’s greatest modern and contemporary art. Maria Manetti Shrem internationally succeeded with her fashion-based entrepreneurial companies, bringing Gucci and Fendi in the departments and specialty stores in the USA.

In joyous partnership the Manetti Shrem couple is bringing their focus and affection to philanthropic causes that advance education, the performing and visual arts, and medicine.

While their lives led them each around the globe, their individual passions eventually brought them to San Francisco Opera and to each other. As Company Sponsors for more than a decade, Jan and Maria have established four generous funds.

- The Conductors Fund helps ensure the continued appearances of noted conductors in the orchestra pit.

- The Great Interpreters of Italian Opera Fund helps bring today’s most compelling artists in Italian repertoire to San Francisco Opera.

- The Emerging Stars Fund supports the Company in showcasing exciting rising young stars on our stage throughout the season.

- The Luminaries Concert Fund enables San Francisco Opera to bring legendary artists to the stage for special events and performances.

In December 2022, Maria received The Spirit of the Opera award for her devotion to San Francisco Opera, her high level of commitment to advancing the success of the Company, and her ongoing support of the art form.

She is the 2023 UC Davis Medal recipient for her profound arts legacy and passion for creating opportunities for exploration and education.

Edmund W. and Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Fund (Production Sponsor, The Magic Flute

Company sponors since 2002, The Littlefield name became especially familiar to opera fans in 2006 when Jeannik Littlefield made her historic $35 million commitment to San Francisco Opera. (The Magic Flute is the 28th production supported by the Littlefield Family.) Jeannik held a subscription for more than 40 years until her passing in 2013. Her daughter, Denise Sobel, continues her family’s wonderful legacy of support as a dedicated benefactor of Opera Ball and production sponsor of The Magic Flute. The Littlefield Family was honored in November 2021 with the San Francisco Opera Guild’s 2021 Crescendo Award alongside the announcement of Sobel’s leadership support of San Francisco Opera’s Department of Diversity, Equity, and Community. The Edmund W. and Jeannik Méquet Littlefield Endowment Fund provides a permanent and unrestricted source of income for the Company.

Carol Franc Buck Foundation (Production Sponsor, The Magic Flute)

The Carol Franc Buck Foundation has generously supported the arts for more than forty years. With a mission to support the visual and performing arts in the western region of the country, the Carol Franc Buck Foundation was created in 1979, providing major underwriting and production grants to the opera companies of San Francisco, Houston, Portland, Nevada, and Arizona, as well as many others. Ms. Buck, who passed away in April 2022, was the youngest child of Frank and Eva Buck, a well-known agricultural, entrepreneurial, and political family in California history, from whom she learned the values associated with contributing to and working in one’s community.

Born in San Francisco, Ms. Buck grew up in and around Vacaville at a time when it was a small rural ranching area. She attended Stanford University, graduating cum laude with a degree in history. She served as the president of the Carol Franc Buck Foundation since its inception, and was an original director of the Frank and Eva Buck Foundation. Ms. Buck was a valued board member of San Francisco Opera from 1981–2022.

The Magic Flute is the 10th production sponsored by the Carol Franc Buck Foundation. San Francisco Opera is indebted to the Foundation for its extraordinarily generous and steadfast support.

Print Edition

Plan Your Visit

Visit SFOpera.com for more information on the following topics

New to opera? First things first, welcome! Second, feel free to skim our short list of good-to-knows before joining us.