In This Program

The Concert

Friday, January 24, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, January 25, 2025, at 7:30pm

Mark Elder conducting

Hector Berlioz

Overture to Les Francs-juges (1826)

Claude Debussy

Prélude à L’Après-midi d’un faune (1894)

Hector Berlioz

Le roi Lear Overture (1831)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Intermission

Richard Strauss

Also sprach Zarathustra, Opus 30 (1896)

John Adams

Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986)

Mark Elder’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

The young Hector Berlioz wrote his Overture to Les Francs-juges for a medieval-themed opera he never finished, and Le roi Lear Overture as a musical impression of Shakespeare’s King Lear. Claude Debussy wrote Prélude à L’Après-midi d’un faune inspired by the symbolist, vaguely Greek mythological poem by Stéphane Mallarmé. And John Adams’s Short Ride in a Fast Machine was a reaction to a nauseating joyride in a Lamborghini.

Overture to Les Francs-juges

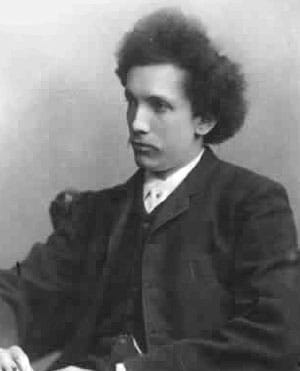

Hector Berlioz

Born: December 11, 1803, in La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died: March 8, 1869, in Paris

Work Composed: 1826

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1971. Seiji Ozawa conducted. Most recent—October 1988. Andrew Massey conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, timpani, percussion (cymbals and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 12 minutes

It was Franz Liszt who molded the symphonic poem (aka tone poem) into a clearly defined genre, a single-movement orchestral work that drew its inspiration, and often its musical structure, from a non-musical source. That source was usually a poem or other literary suggestion of a character, place, or plot, but sometimes symphonic poems were prompted by a visual artwork. Although Liszt’s 13 symphonic poems served to codify the genre, they were not without clear precedents. Among their direct ancestors were the dramatic or depictive overtures of the early 19th century, some of which were symphonic poems in all but not-yet-invented name. Prominent among these were several concert overtures by Hector Berlioz. Some were conceived as standalone pieces but, based on content rather than context, they could be essentially indistinguishable from certain overtures that were crafted to introduce larger works, particularly operas. We hear two of Berlioz’s proto-symphonic poems in this concert: the Les Francs-juges Overture, written to prefigure an opera that never made it to the stage, and the Le roi Lear Overture, inspired by Shakespeare’s King Lear but intended to be played as a concert piece rather than in connection with a dramatic production of that play.

Graduating from the Paris Conservatory was a virtual prerequisite for aspiring French composers; and almost as crucial was snaring the Prix de Rome, a fellowship that provided a residency in Rome, whose cultural lineage was considered indispensable to the creative intellect. Berlioz cleared both those hurdles. A third qualification was a success in the opera house. He never achieved that during his lifetime, but in the course of his commercial failures he created a body of stage music that remains captivating to this day.

The Music

His first operatic failure was the three-act “lyric drama” Les Francs-juges, a gloomy opera about secret tribunals in medieval Germany, which he worked on in 1825–26. The hard-to-translate title might be rendered as “The Self-Appointed Judges” and is sometimes given as “The Judges of the Secret Court.” After futile attempts to get the opera produced, Berlioz destroyed most of what he composed, such that only five of the dramatic numbers survive. But he never let go of the overture, which he composed in September 1826, and he frequently conducted on concert tours.

This 12-minute movement embodies a swashbuckling character that is unmistakably appealing. Its idiosyncratic sound, particularly at the Overture’s climax, somewhat prefigures the slightly later Symphonie fantastique. As the Berlioz biographer D. Kern Holoman has rightly remarked, “It is a dubious undertaking to judge the overture without knowing just how it relates to the opera that followed.” In this case, we have no choice. It is the only music from Berlioz’s first opera that we are likely to hear—or at least that we are likely to hear in its roughly original form, since he did recycle some of this project into his Symphonie fantastique and his Symphonie funèbre et triomphale.

Prélude à L’Après-midi d’un faune

Claude Debussy

Born: August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Died: March 25, 1918, in Paris

Work Composed: 1892–94

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1912. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—January 2023. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 harps, antique cymbals, and strings

Duration: About 10 minutes

Claude Debussy achieved musical maturity in the final decade of the 19th century, a magical moment in France when aficionados of the visual arts fully embraced the gentle luster of impressionism, composers struggled with the pluses and minuses of Richard Wagner, poets navigated the indirect locutions of symbolism, and the City of Light blazed with the pleasures of the Belle Époque. Symbolism enveloped itself in vagueness. A manifesto for the movement, published in 1886, declared that symbolist poetry was the “enemy of education, declamation, wrong feelings, [and] objective description.” And, deeper in: “The essential character of Symbolic art consists of never approaching the concentrated kernel of the Idea in itself. So, in this art movement, representations of nature, the actions of human beings, all concrete phenomena do not stand on their own; instead, they are veiled reflections of the senses pointing to archetypal meanings through their esoteric connections.”

A highpoint of symbolist poetry was L’Après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun), by Stéphane Mallarmé. It first appeared in 1865 under the title Monologue d’un faune and then kept evolving until it reached a definitive version in 1876. At that point Mallarmé published it, under its new title, in a slim volume embellished with a drawing by Édouard Manet. Vintage symbolism it is: a faun (a rural deity that is half man, half goat) spends a languorous afternoon observing, recalling, or fantasizing about—it’s not always clear which—some alluring nymphs who clearly affect him in an erotic way. The poem was iconic in its time (though it was merely a point of departure for Mallarmé’s further, even more revolutionary poetry) and Debussy fell beneath its spell by the early 1890s, when he seems to have discussed with Mallarmé the idea of creating a musical parallel.

He completed the score of his symphonic poem in October 1894, and two months later the piece was premiered to such enthusiasm that it was encored. The composer described it as “a very free illustration . . . a succession of settings through which the Faun’s desires and dreams move in the afternoon heat.” It was radical in its unremitting sensuality, but the work’s harmonic implications were also profound. In retrospect, the Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun was a harbinger of the musical century that lay ahead. Pierre Boulez would write: “It has been said often: the flute of the Faune brought new breath to the art of music; what was overthrown was not so much the art of development as the very concept of form itself, here freed from the impersonal constraints of the schema, giving wings to a supple, mobile expressiveness, demanding a technique of perfect instantaneous adequacy. . . . The potential of youth possessed by that score defies exhaustion and decrepitude; and just as modern poetry surely took root in certain of Baudelaire’s poems, so one is justified in saying that modern music was awakened by L’Après-midi d’un faune.”

Le roi Lear Overture

Hector Berlioz

Work Composed: 1831

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, cornet, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 15 minutes

Berlioz finally won the Prix de Rome in 1830, on his fifth attempt, and he arrived in Rome the following March. The customary drama of his life immediately escalated, this time even more than usual. He decided he would rather be back in France, near his fiancée, the pianist Camille Moke. Setting foot outside Italy would spell automatic forfeiture of his fellowship, but within a couple of weeks he nonetheless began his journey north. When he got to Florence, he received a letter from his prospective mother-in-law; she informed him that she was cancelling the engagement, and that her daughter would instead marry the piano-maker Camille Pleyel. Years later, in his Memoirs, Berlioz wrote: “Two tears of rage started from my eyes, and instantly I knew my course. I must go post-haste to Paris and there kill without compunction two guilty women and one innocent man. As for subsequently killing myself, after a coup on this scale it was of course the least I could do.” His hot head cooled by the time he reached Nice, at that time part of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia rather than France, and he retreated to Rome, which he decided he liked after all.

But he stayed in Nice for about a month before returning, and during those weeks he composed Le roi Lear. Berlioz had first been smitten with Shakespeare in 1827, and the Bard remained a lifelong passion, giving rise to such works as the concert overture La tempête (The Tempest), the song La mort d’Ophélie (from Hamlet), the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette, and the opera Béatrice et Bénédict (after Much Ado About Nothing). King Lear was on his reading list while in Florence. “That is where I read for the first time King Lear,” he wrote to a friend, “and I screamed with admiration for this work of genius. I thought I would suffocate in my enthusiasm, and rolled around—in the grass, admittedly, but I did roll around convulsively to give vent to my excitement.” Shakespeare was the impetus for this work, but inspiration also came from a composer Berlioz admired to a similar degree: Beethoven, whose ghost seems to hover at the edge of this score.

Although Berlioz did not provide a programmatic summary of the piece’s “plot,” commentators have long identified the opening theme with Lear and the ensuing oboe melody with his daughter Cordelia. It is beyond doubt that Berlioz had a narrative in mind. In 1858, he wrote to an admirer about an ancient tradition in the French court of announcing the king’s entrance with a five-beat drum cadence. “This gave me the idea of accompanying Lear’s entrance to his council chamber for the scene where he divides his states with a similar figure on the timpani. As for the king’s madness, I only intended to portray it toward the middle of the Allegro when the lower strings take up the theme of the introduction during the storm.”

Also sprach Zarathustra

(Thus Spoke Zarathustra), Opus 30

Richard Strauss

Born: June 11, 1864, in Munich

Died: September 8, 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany

Work Composed: 1895–96

SF Symphony Performances: First—October 1919. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—September 2022. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, piccolo (3rd flute doubling second piccolo), 3 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 6 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, chime, bass drum, and glockenspiel), 2 harps, organ, and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

The symphonic poem was greatly associated with the “Music of the Future” camp, the radical composers who supported the advances of Berlioz, Liszt, and Wagner. Richard Strauss became linked to that circle via Alexander Ritter, a violinist and composer who married a niece of Wagner’s, composed six symphonic poems, and eventually became associate concertmaster of the Meiningen Court Orchestra, where Strauss was named assistant music director in 1885. Strauss said that Ritter opened his eyes to the possibilities of the symphonic poem. He was drawn to the idea (as he recalled in his memoirs) that “new ideas must search for new forms; this basic principle of Liszt’s symphonic works, in which the poetic idea was really the formative element, became henceforward the guiding principle for my own symphonic work.” Many consider Strauss’s nine symphonic poems to represent the pinnacle of the genre.

He immersed himself in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche in the early 1890s and was impressed by the philosopher’s attacks on formalized religion, which mirrored his own stance. Nietzsche’s philosophy had just then reached its mature formulation, and it was articulated most completely in his four-part treatise Also sprach Zarathustra (published 1883–85). There the philosopher speaks in a prose narrative (as opposed to the solemn style of traditional philosophical treatises) through the voice of Zarathustra, a fanciful adaptation of the Persian prophet Zoroaster, who spends years meditating on a mountaintop and then descends to share his insights with the world. Most of the catchphrases popularly associated with Nietzsche—“God is Dead,” the “Will to Power,” the “Übermensch” or “Superman”—appear as keystones in these volumes. Nietzsche’s ideas went to the heart of human existence and aspiration, which he viewed (pessimistically) as an endless process of self-aggrandizement and self-perpetuation, over which the much-heralded achievements of civilization—morality, religion, the arts—stand merely as pleasant distractions from the underlying banality of humanity.

Nietzsche’s text, Strauss wrote to his friend Romain Rolland, was “the starting point, providing a form for the expression and the purely musical development of emotion.” Indeed, it would be difficult for a listener not armed with a score to follow anything but a musical narrative in this tone poem, which Strauss conducted at its premiere, in Frankfurt in 1896. Nonetheless, a sort of narrative does exist, and following the stentorian fanfares of the work’s famous introduction, Strauss inscribed textual indications in the score to punctuate the sections of the piece’s program: “Of Those of the Unseen World,” “Of the Great Longing,” “Of Joy and Passions,” “The Dirge,” “Of Science,” “The Convalescent,” “Dance Song,” “Night Wanderer’s Song.” This last is sometimes given as “Song of Those Who Come Later,” the discrepancy resulting from an apparent misprint in the score whereby Nachtwandlerlied is misspelled as Nachwandlerlied. The consensus is that that the former (meaning “Night Wanderer’s Song”) is correct.

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

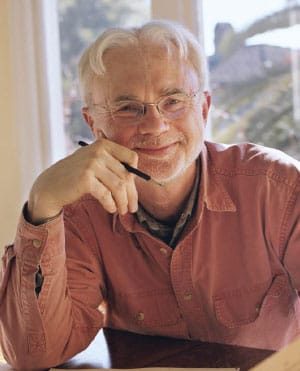

John Adams

Born: February 15, 1947, in Worcester, Massachusetts

Work Composed: 1986

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1986. Edo de Waart conducted. Most recent—July 2017. Edwin Outwater conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 piccolos, 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 4 clarinets, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion (woodblocks, pedal bass drum, snare drum, large bass drum, suspended cymbal, sizzle cymbal, large tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, glockenspiel, xylophone, and crotales), 2 synthesizers, and strings

Duration: About 4 minutes

The heyday of the symphonic poem was the second half of the 19th century and the opening years of the 20th, when stellar examples were put forward by such composers as Smetana, Saint-Saëns, Franck, Tchaikovsky, Dukas, Dvořák, and Rachmaninoff, apart from Strauss. The concept persevered a bit longer in England and the United States, with the latter furnishing such notable (if now neglected) works as Charles Tomlinson Griffes’s The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan (1916, after Coleridge) and Ernest Bloch’s America (1926, inspired by Walt Whitman). On the whole, though, the genre was ceding its place to works that were descriptive without deriving from a parallel literary or pictorial source. Some of these pieces drew inspiration from an experience—Charles Ives’s Central Park in the Dark (1906), John Alden Carpenter’s Adventures in a Perambulator (about a day in the life of his baby daughter in 1914), George Gershwin’s An American in Paris (strolling that city’s streets in 1928), Aaron Copland’s El Salón México (1933–36, evoking a dance hall in Mexico City), and Duke Ellington’s Harlem (1950, which he called a “tone parallel” to that neighborhood). A handful of 20th-century descriptive symphonic movements were inspired by modes of transportation, such as Jean Sibelius’s Night Ride and Sunrise (1908, sledding), Arthur Honegger’s Pacific 231 (1925, a locomotive), and Henry Hadley’s Scherzo diabolique (1934, a fast car trying to catch a train).

John Adams’s Short Ride in a Fast Machine is a more recent entry in that tradition, a descriptive symphonic movement—a virtual tone poem—inspired by a vehicle. He has described it as “a cranked-up, high-velocity orchestral juggernaut, insistently urged on by the unyielding pulse of the wood block.” Its specific inspiration, he reports, relates to an incident many years ago on Cape Cod, when a brother-in-law took him out for a late-night spin in a Lamborghini, a ride that left the composer dazzled but wishing he hadn’t gone—“both thrilling and also kind of a white-knuckle, anxious experience.”

Adams is well known to San Francisco Symphony audiences; the Orchestra has championed his music for decades, and from 1982–85 he was the ensemble’s first composer-in-residence. He wrote Short Ride in a Fast Machine in 1986 at the invitation of Michael Tilson Thomas, who nine years later would become the San Francisco Symphony’s Music Director. It was conceived as a fanfare to open a concert at a music festival in Massachusetts, and MTT conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony at its premiere, on June 13, 1986. Although Adams’s musical style is too variegated to pigeon-hole, this piece reminds us of his early minimalist leanings, incorporating rhythmic repetitions, brilliant sonority, and a sense of harmonic consonance. It also owes some of its propulsive energy to the big bands of the swing era (he points to “the signature jabs and ‘bullets’ of the Ellington brass”), and it’s hard not to hear Adams’s American roots in the Coplandesque open intervals proclaimed by the brass.

—James M. Keller

About the Artist

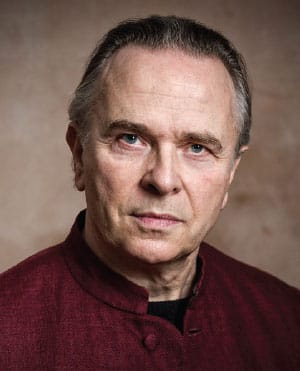

Mark Elder

Mark Elder was music director of the Hallé from 2000–24 and now holds the position of conductor emeritus. He was previously music director of English National Opera and principal guest conductor of the BBC Symphony and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. In 2023 he took up the post of principal guest conductor of the Bergen Philharmonic. Elder has enjoyed long relationships with the London Philharmonic and London Symphony, as well as working with leading symphony orchestras throughout the world. He is a principal artist of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and has appeared annually at the Proms for many years, including twice for the internationally televised Last Night. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

Elder has enjoyed a long association with the Royal Opera House and has appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, Paris Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Zürich Opera, Dutch National Opera, Chicago Lyric Opera, San Francisco Opera, and Glyndebourne Festival Opera. He was the first English conductor to conduct a new production at the Bayreuth Festival. From 2011 to 2019 he was artistic director of Opera Rara, with which he has made many award-winning recordings, and he has recorded a wide repertoire with the Hallé, including Wagner’s Ring cycle and Parsifal, as well as the three great Elgar oratorios.

Elder was appointed a companion of honour in 2017, knighted in 2008, and awarded the CBE in 1989. In May 2006 he was named “conductor of the year” by the Royal Philharmonic Society and he was awarded honorary membership of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 2011. He holds the Barbirolli Chair at the Royal Academy of Music.