In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, January 30, 2025, at 2:00pm

Friday, January 31, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, February 1, 2025, at 7:30pm

Herbert Blomstedt conducting

Franz Schubert

Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, D.485 (1816)

Allegro

Andante con moto

Menuetto: Allegro molto

Allegro vivace

Intermission

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Opus 68 (1876)

Un poco sostenuto–Allegro

Andante sostenuto

Un poco allegretto e grazioso

Adagio–Più andante–Allegro ma non troppo, ma con brio

These concerts are presented in honor of the San Francisco Symphony Life Governors in gratitude for their incredible years of service.

Herbert Blomstedt’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

Thursday matinee concerts are endowed by a gift in memory of Rhoda Goldman.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Johannes Brahms worked on his Symphony No. 1 for more than 20 years, in fitful bursts, followed by bouts of recrimination and revision. He fretted obsessively about living up to Beethoven’s example: “You have no idea what it’s like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you.” The finale’s glorious chorale theme sounds so much like the master’s famous “Ode to Joy” melody that Brahms supposedly snapped, “Any jackass can see that!” when someone made the mistake of mentioning it.

Schubert and Brahms

Most tourists who include Vienna’s Central Cemetery on their itinerary make a beeline for the conclave of composers clustered together in Group 32a. Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert had originally been buried about nine miles away, but both were exhumed in 1888 and reinterred at 32a, Beethoven in Grave No. 29, Schubert in No. 25. The real estate abutting both was obviously choice, and when his time came, in 1897, Johannes Brahms was deemed worthy of Grave No. 26, right by Schubert.

He doubtless lies there contentedly. Probably both of them do. Schubert, of course, would have known nothing of Brahms, who was born in 1833, four-and-a-half years after Schubert’s passing. But Brahms knew a great deal of Schubert. In fact, he was one of the leading authorities on Schubert’s music as it staked a posthumous place in musical life during the second half of the 19th century. Although we don’t know for sure, it seems likely that Brahms learned pieces by Schubert as a young man growing up in Hamburg. From the age of 10, he took piano lessons from Eduard Marxsen, who remained a lifelong friend. Marxsen had received most of his musical education in Vienna, where he was a piano pupil of Karl Maria von Bocklet, a revered virtuoso who was one of the few prominent proponents of Schubert’s music while the composer was alive. Brahms developed into a fine pianist, but at some point he gave up practicing and his technique became shambolic. In February 1856, he wrote to his confidante Clara Schumann, the eminent pianist, who had recently programmed Schubert’s music: “I was so glad you played some Schubert. . . . If I were a moderately respected pianist and one worthy of respect, I would long ago have played one of the sonatas in public (for instance, the one in G). It is bound to delight people, if played well.”

In fact, he did play Schubert’s music in concerts—the B-minor Rondo with his violinist-friend Joseph Joachim, the piano trios and Trout Quintet with colleagues—although indeed none of the sonatas. He served as pianist for song recitals by the distinguished baritone Julius Stockhausen, and in 1861 they joined up to perform Winterreise in Hamburg. (Stockhausen was an authority on the piece, having been the first person to sing the complete cycle in a public concert, which he did in Vienna in 1856.) Many Schubert works that we consider core repertoire reached the public only around the middle of the 19th century. His Great C-major Symphony fared better than most, being premiered in 1829 in Vienna, and music-lovers in Hamburg did hear it twice in the 1840s. Brahms didn’t attend either of those concerts, and he first encountered the piece in December 1853 at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. After the performance, he wrote to Joachim, “Few things have so enchanted me.”

Schubert was born-and-bred Viennese—or, to be precise, he was born in a Vienna suburb that was later merged into the city. Brahms would also become one of Vienna’s musical all-stars, but he did not set foot there until he was 29 years old. His first visit lasted eight months, from September 1862 to May 1863, and during that time he became friendly with the music publisher Carl Anton Spina, who released the first editions of many Schubert compositions, including such seminal works as the Unfinished Symphony and the supernal String Quintet. Spina presented Brahms with a copy of every Schubert piece his firm had published to date, and he allowed him to make copies of unpublished Schubert manuscripts he owned. During that visit, Brahms wrote to a friend, “Altogether I owe my happiest hours here to unpublished works by Schubert, of which I have a large number at home in manuscript.”

He acquired a particularly curious item while turning over manuscripts at Spina’s office: the sand Schubert had scattered on the pages to blot the ink while writing his oratorio Lazarus. Brahms scraped off some of these grains and kept them in a box, like a sacred relic. He was an inveterate collector and started buying composers’ manuscripts himself. His collection grew into something extraordinary, and he bequeathed it to Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of the Friends of Music). By that time, his holdings included not only a plethora of Schubert first editions (including of Winterreise and Schwanengesang) but also many of his autograph manuscripts, among them the Quartettsatz (D.703, for which he anonymously underwrote the publication), a number of songs, and no fewer than 113 dances. His biographer Karl Geiringer wrote, “Hardly any of Schubert’s works known at that time were missing from Brahms’s library.” Brahms had a long relationship with the Gesellschaft, and he served as its director from 1872–75. In the opening concert of his tenure, he included Schubert’s Grand Duo for piano four-hands, in a symphonic arrangement by Joachim. For all his admiration of Schubert, Brahms remained always a critical listener. In fact, he had dismissed the Grand Duo in an 1858 letter to Clara Schumann, complaining, “There are no melodies in it! It is boring!” This contrasts with what his acolyte Florence May reported in her 1905 Brahms biography: “He especially loved Schubert, and I have heard him declare that the longest works of this composer, with all their repetitions, were never too long for him.”

Brahms published his own orchestrations of six Schubert songs, of which “Ellens Gesang II” is the most fascinating. He actually created two different orchestrations; in the first, from 1862, he echoed the hunting metaphors in the text (penned by Sir Walter Scott) by accompanying the solo soprano with a quartet of horns and three bassoons, while his second (premiered at the Gesellschaft in 1873) uses the four horns plus only two bassoons, along with the soprano and a women’s chorus.

Did Schubert serve as a model for Brahms’s own compositions? Doubtless he was a source of inspiration, although not as obviously as Beethoven was. Musicologists have spied Schubert’s imprint on a number of Brahms’s works—the influence of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy on Brahms’s Piano Sonata No. 1, for example, or of Schubert’s String Quintet on Brahms’s String Sextet No. 2, or of Schubert’s Lazarus on Brahms’s cantata Rinaldo. Late in life, Brahms even transformed “Der Leiermann,” the concluding song of Winterreise, into “a doleful canon for women’s voices.”

The Breitkopf und Härtel publishing company issued an ostensibly complete edition of Schubert’s works in 39 volumes from 1884–97. Brahms was among the luminaries the company approached to participate in the venture. Brahms insisted that he was not a fan of “complete editions” in general—he felt they gave undeserved prominence to negligible pieces—and he was especially wary about the posthumous publication of works, which, after all, did not allow deceased composers the opportunity to polish things as they might have when alive. In fact, he tried to talk B&H out of undertaking their edition; but when they would not be persuaded, and since it was Schubert, Brahms consented to serve as editor for the two volumes devoted to the composer’s symphonies, of which only the Unfinished and the Great C-major had previously been available in print. He was probably also acquainted with Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 by then, as it was almost certainly one of the pieces he had examined at Spina’s in 1862–63. Florence May wrote: “A large number of [Schubert’s] half-forgotten manuscripts—those of the Octet, the C-major Quartet, the B-flat and B-minor Symphonies amongst them—were found by Spina . . . and were gradually placed by him in the possession of the world.” Thus it came to pass that Brahms, who composed the second half of today’s program, was the first editor of the work that occupies the opening half.

Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, D.485

Franz Schubert

Born: January 31, 1797, in Vienna

Died: November 19, 1828, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1816

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1916. Alfred Hertz conducted Most recent—October 2021. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, and strings

Duration: About 27 minutes

Franz Schubert’s sunny Symphony No. 5 was rightly described by the musical commentator Donald Francis Tovey as “a pearl of great price.” It delights at every turn yet seems comfortable within its unostentatious limits. Schubert was 19 years old when he produced this pearl, and Vienna’s heady musical world was in no way his oyster. In fact, it could not yet be said that music was his profession, strictly speaking, since he unhappily endured his working hours as an assistant teacher in his father’s school. But he had already composed a good deal of music, including four symphonies, and he was on a roll, producing new compositions hand over fist.

Many of his pieces were unveiled in at-home musicales. These had begun, in about 1814, as Sunday-afternoon family string-quartet sessions in which his older brothers played violins, he played viola, and his father played cello. Friends started sitting in, and by the autumn of 1815 the group even included some professionals. Its more-or-less dependable membership had swelled to comprise seven first violins, six second violins, three violas, three cellos, and two double basses, plus whatever wind instruments could be brought in, and the group moved from the Schuberts’ living room to larger venues. The ensemble stayed together for about three years, eventually performing for themselves and a small audience at the home of its concertmaster, Otto Hatwig, a Bohemian-born violinist in the Burg Theatre orchestra and a composer of modest talent.

Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 is scored for a very small orchestra, a fact that is generally explained away by noting the forces available in this genial ensemble. But Schubert’s first four symphonies were also written for these players, and all of them use a richer orchestration. In the Fifth, Schubert limits himself to a single flute (harking back to his First Symphony, and to most of Haydn’s and Mozart’s), and he dispenses entirely with clarinets, trumpets, and timpani, which were more or less standard orchestral instruments by 1816. Schubert seems to be going out of his way to “think small” in this last stand of Viennese Classicism. It is as if he were picking up where Mozart had left off a quarter of a century earlier, hardly grappling with the huge advances that Beethoven had effected in the meantime. In fact, Mozart was the young Schubert’s musical idol; only later did he embrace Beethoven’s music with as ardent a passion.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor seems to have inspired Schubert here. The second theme of Schubert’s graceful first movement sports a melody, harmony and bass line very like the corresponding passage in Mozart’s, and the dialogue between winds and strings also recalls the earlier composer. The elegant second movement recalls late Mozart in its harmonic exploration, and the third has a similar spirit to the minuet-and-trio in Mozart’s symphony—not quite ill-humored, but blustery and no-nonsense, even if it lacks the metric quirks of Mozart’s movement. The finale seems also quite “18th-century,” although Haydn, rather than Mozart, serves as a model for both the principal theme and the development of the movement as a whole.

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Opus 68

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1855–76

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1912. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—January 2022. Christoph Eschenbach conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, and strings

Duration: About 45 minutes

“I shall never write a symphony!” Brahms famously declared in 1872 to the conductor Hermann Levi. “You can’t have any idea what it’s like to hear such a giant marching behind you.” The giant was Beethoven, and although Beethoven’s music provided essential inspiration for Brahms, it also set such a high standard that the younger composer found it easy to discount his own creations as inconsequential in comparison.

Nonetheless, he proved relentless in confronting his compositional demons. Rather than lead to a creative block, his self-criticism pushed him to forge ahead even when his eventual path seemed obscure. He drafted the first movement of this symphony in 1862, just before his first trip to Vienna, and shared it with Clara Schumann. She copied out the opening and sent it along to their friend Joachim with this comment: “That is rather strong, for sure, but I have grown used to it. The movement is full of wonderful beauties, and the themes are treated with a mastery that is becoming more and more characteristic of him. It is all interwoven in such an interesting way, and yet it moves forward with such momentum that it might have been poured forth in its entirety in the first flush of inspiration.” She then jotted a musical example—essentially the spot where the main section of the first movement begins (Allegro) following the slower introduction. Calling the opening “rather strong” is an understatement. That first movement’s introduction is one of the most astonishing preludes in the entire symphonic literature, with throbbing timpani, contrabassoon, and double basses underpinning the orchestra’s taut phrases—a texture that seizes the listener’s attention and remains engraved in the memory.

Word got around that Brahms was working on a symphony, and he started deflecting inquiries about his progress, most pointedly from his eager publisher, Fritz Simrock. Eleven years later, Simrock wrote a beseeching letter to the composer: “Aren’t you doing anything anymore? Am I not to have a symphony from you in ’73 either?” He was not—nor in ’74 or ’75 either. Not until 1876 did Brahms finally sign off on his First Symphony, at least provisionally, since he would revise it further prior to its publication the following year. He was 43 years old and had been struggling with the piece on and off for 14 years.

The Music

“My symphony is long and not particularly lovable,” wrote Brahms to his fellow composer Carl Reinecke when this piece was unveiled. He was right about it being long, at least when compared to typical symphonies of his era. He was probably also right about it not being particularly lovable. Even the warmth of the second movement and the geniality of the third are interrupted by passages of anxiety, and the outer movements are designed to impress rather than to charm. Brahms’s First is a big, burly symphony, certainly when compared to his next one. It is probably no more “lovable” than Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment, Shakespeare’s King Lear, or Goethe’s Faust.

The symphony’s dominant expression is articulated in its outer movements; against these, the second and third movements stand as a two-part intermezzo, throwing the weighty proceedings that surround them into higher relief. The four movements proceed according to a key arrangement of ascending thirds: the first movement in C minor, the second in E major, the third in A-flat major (the enharmonic equivalent of G-sharp), and the finale in C minor again. In this regard we find that Brahms was not following any model he could have found in Beethoven’s symphonies, which for the most part still operated according to the Classical era’s harmonic relationships of fourths or fifths. Instead, Brahms explores an architecture based on thirds-relationships, a mid-century fascination that had evolved from its obsessive use by . . . can you guess? Yes, it was a distinctive fingerprint of Franz Schubert.

—James M. Keller

About the Artist

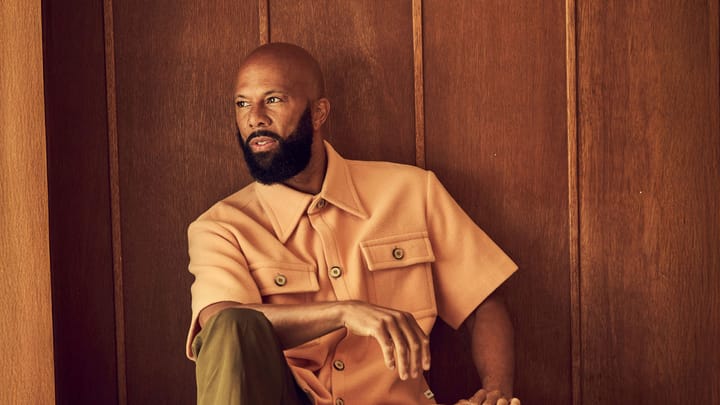

Herbert Blomstedt

Noble, charming, sober, modest. Such qualities may play a major role in human coexistence and are certainly appreciated. However, they are rather atypical for extraordinary personalities such as conductors. Whatever the general public’s notion of a conductor may be, Herbert Blomstedt is an exception, precisely because he possesses those very qualities which seemingly have so little to do with a conductor’s claim to power. That he disproves the usual clichés in many respects should certainly not lead to the assumption that he does not have the power to assert his clearly defined musical goals. Anyone who has attended Blomstedt’s rehearsals and experienced his concentration on the essence of the music, the precision in the phrasing of musical facts and circumstances as they appear in the score, the tenacity regarding the implementation of an aesthetic view, is likely to have been amazed at how few despotic measures were required to this end. Basically, Blomstedt has always represented that type of artist whose professional competence and natural authority make all external emphasis superfluous. His work as a conductor is inseparably linked to his religious and human ethos, and his interpretations combine great faithfulness to the score and analytical precision, with a soulfulness that awakens the music to pulsating life. In the more than 60 years of his career, he has acquired the unrestricted respect of the musical world.

Born in the United States to Swedish parents and educated in Uppsala, New York, as well as in Darmstadt and Basel, Blomstedt gave his conducting debut in 1954 with the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and subsequently served as chief conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic, the Swedish and Danish radio orchestras, and the Dresden Staatskapelle. Later he became music director of the San Francisco Symphony, chief conductor of the NDR Symphony Orchestra, and music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. His former orchestras in San Francisco, Leipzig, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Dresden, as well as the Bamberg Symphony and the NHK Symphony Orchestra, all honored him with the title of Conductor Laureate. Since 2019, he has been an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic.

Blomstedt holds several honorary doctorates, is an elected member of the Royal Swedish Music Academy, and was awarded the German Great Cross of Merit with Star. Over the years, leading orchestras around the globe have been fortunate to secure the services of the highly respected Swedish conductor. At the high age of 97, he continues to be at the helm of all leading international orchestras with enormous presence, verve, and artistic drive.