In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, October 27, 2024, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano and harpsichord

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Harpsichord in A major, BWV 1015 (ca. 1717–23)

[Andante]

Allegro

Andante un poco

Presto

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonata No. 3 for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord in G minor, BWV 1029 (trans. for cello) (ca. 1736–41)

Vivace

Adagio

Allegro

Intermission

Franz Schubert

Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat major, D.929 (1827)

Allegro

Andante con moto

Scherzo: Allegro moderato–Trio

Allegro moderato

This series showcases the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin on loan to Alexander Barantschik and the San Francisco Symphony from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Program Notes

Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Harpsichord in A major, BWV 1015

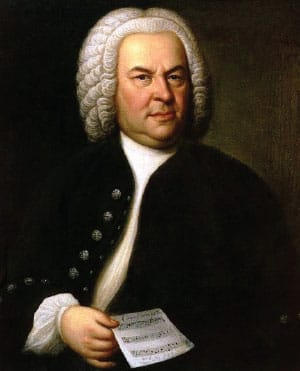

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: March 21, 1685, in Eisenach, Germany

Died: July 28, 1750, in Leipzig

Work Composed: ca. 1717–23

Johann Sebastian Bach was acclaimed as one of the supreme keyboard virtuosos of his time, but he was also a highly skilled violinist. His father had been a professional violinist in the Thuringian cities of Erfurt and in Eisenach (where Johann Sebastian was born), so our composer surely grew up surrounded by the sounds of the instrument. It was as a violinist that he obtained his first professional appointment, at Weimar in 1703, and when he died 47 years later, he left in his estate a violin built by Stainer—very likely the Austrian luthier Jacob Stainer whose instruments remained prized today. Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel, responding to a biographical query in 1774, recalled of his father: “From his youth up to fairly old age he played the violin purely and with a penetrating tone and thus kept the orchestra in top form, much better than he could have from the harpsichord. He completely understood the possibilities of all stringed instruments. His solos for violin and cello without bass bear witness to this.”

His sonatas for violin and keyboard fall into two varieties. Two of them, BWV 1021 and 1023, are typical in their externals of what late-Baroque listeners would have expected of a violin sonata; the violinist is clearly the soloist, and the keyboard player participates in a continuo group that plays mostly a harmonic, and only incidentally a melodic, role. The other six, however, were revolutionary in the way they employed the two instruments. In those six works, BWV 1014–19, the keyboard instrument plays an obbligato role as an equal melodic partner to the violin while also fulfilling its traditional role as accompanist (possibly alone, possibly assisted by other instruments). It is often remarked that these six pieces are effectively trio sonatas in which the violin and the keyboard’s right-hand part serve as the joint “melody soloists” while the left-hand provides the accompaniment. Many of the movements do indeed behave that way, but elsewhere the music is cast in highly contrapuntal writing of three or even four parts, with an alternation of textures that suggests a concerto—or movements may resemble an aria with an accompaniment that sounds as if it is a keyboard reduction from a piece originally conceived with orchestra. Carl Philipp Emanuel did refer to these pieces as “harpsichord trios,” and the earliest source for the set titles them “Six sonatas for obbligato harpsichord and solo violin, with the bass accompanied by a viola da gamba if you like.” In this concert, however, the performers use only violin and harpsichord.

The chronology of these works is elusive. They probably date from the composer’s years at the Court of Anhalt-Cöthen, where he served as Kapellmeister from December 1717 until May 1723, after which he moved to Leipzig for the remainder of his career. Since Bach’s original manuscripts have gone missing, these pieces come down only in numerous copies that appear to post-date their composition by several years. The earliest extant source is a copy of the keyboard part written out mostly by Johann Heinrich Bach (the composer’s nephew) and completed by Johann Sebastian himself, and that manuscript dates from 1725, two years into Bach’s Leipzig years.

The A-major violin sonata, the second of the six, is both idiomatic and technically demanding in its violin-writing. Although the first movement lacks a tempo marking, it can be assumed to be an Andante, and an early source designates it dolce (sweetly). It does exude tenderness; one could imagine it transformed into the opening sinfonia of a cantata on a comforting topic. In the first measures, the theme is presented sequentially by violin, then harpsichord right-hand, then harpsichord left-hand—all in the same key, yielding a static quality. This suggests a canon, although Bach soon abandons canonical rigor for freer imitative counterpoint.

The second movement, similarly, has fugue-like passages without being a strict fugue. This is one of the concerto-like movements, its ritornello structure attesting to Bach’s fascination with the new style of Vivaldi wafting up from the south.

Canon was hinted at in the first movement. In the third it is played out rigorously, the violin and the harpsichord right-hand intoning exactly the same melody at the distance of one measure over a staccato walking bass line. Very brainy stuff. The high-spirited fourth movement is again fugal though not a strict fugue—more like a three-part invention. Near the end, Bach intensifies the contrapuntal brilliance through a stretto—a passage in which the theme overlaps with itself—here echoing itself at the distance of just one beat.

Sonata No. 3 for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord in G minor, BWV 1029

Johann Sebastian Bach

Work Composed: ca. 1736–41

Bach’s three sonatas for viola da gamba and obbligato harpsichord lack ironclad genealogies. Current musicological consensus is that he produced them sometime during his years in Leipzig, most likely in the period 1736–41. It was formerly held (and still considered possible) that he recast them from pre-existing pieces, arranging them for one or the other of the well-known viola da gamba players Carl Friedrich Abel or Ludwig Christian Hesse. The viola da gamba was an essential instrument in Bach’s day, a large bowed viol with six or seven strings and a fretted fingerboard, balanced upright somewhat in the mode of a cello. Indeed, modern cellists can comfortably assume Bach’s gamba repertoire, as here, even though their instruments are constructed on different principles from the viola da gamba.

The predominant texture of the sonatas for viola da gamba and keyboard is that of the trio sonata, with the keyboard instrument assuming a solo line in the right hand to play as an equal partner to the gamba, and the left hand handling the bass line. Even musicologists who believe that the G-minor Gamba Sonata is a transcription are not certain precisely what it is a transcription of. At least the first and third movements use recurring ritornello episodes with fugal counterpoint, characteristics that point to the likelihood that Bach originally wrote at least those movements for a concerto grosso or a concerto spotlighting who-knows-what instrument. One could imagine this music finding a place in a concerto, showing some similarity of process and spirit to the analogous movements of the Fifth and Sixth Brandenburg Concertos. In fact, the late gambist John Hsu published exactly such a re-imagined setting in 1984, elaborating this sonata into a concerto for two violas, two violas da gamba, cello, and basso continuo—the same scoring as the Sixth Brandenburg Concerto. The middle movement, with its graceful dignity and slow, triple-time meter, has been viewed as a combination of an elegantly decorated Italian adagio (in the gamba part) and a French sarabande (in the keyboard), with the two instruments not so much interacting as superimposing.

Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat major, D.929

Franz Schubert

Born: January 31, 1797, in Vienna

Died: November 19, 1828, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1827

Of Franz Schubert’s two late-in-life piano trios, the one in B-flat major scored no immediate success, although its gracious, convivial spirit eventually won it the upper hand in popular affection. The more intellectual one, in E-flat major, fared better when it was new. The composer apparently heard it on three occasions. At its premiere, on December 26, 1827, in the hall of Vienna’s Musikverein, it was played by violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh, cellist Josef Linke, and pianist Karl Maria von Bocklet. On January 28, 1828, the same musicians likely played it at a Schubertiade (a private gathering of Schubert’s circle), and on March 26 it was repeated at the Musikverein (with Josef Böhm replacing the indisposed Schuppanzigh) as the centerpiece of the only public all-Schubert concert ever held during the composer’s lifetime. Two weeks after that, in a letter to the Leipzig publisher H.A. Probst, Schubert reported that the trio had been “received at my concert by a tightly packed audience with such extraordinary applause that I have been urged to repeat the concert”—an idea that came to naught. It appears to have been the only one of Schubert’s pieces to be published outside Austria in his lifetime, since Probst released an edition in Leipzig in October 1828. Whether Schubert received a copy of the printing before his death is not known, but at least he knew its publication was imminent. “This work will not be dedicated to any one person,” he had written to Probst, “but rather to all who find pleasure in it. That is the most profitable form of dedication.”

Schubert rarely gives the impression of being in a hurry. True to form, this trio unrolls over a very generous span of time, usually running more than 40 minutes. The composer himself sensed that it could use some editing, and he effected a lengthy cut in the finale, the longest of the four movements. Though this material was restored by the editors of the complete edition of Schubert’s works, it is rarely played today. Elsewhere, passages are sometimes repeated wholesale or with rather little alteration.

The propulsive first movement is largely developed from the contours of the opening motif (proclaimed by all three instruments in unison), from a counter-statement (first intoned by the cello), and from a gentler second theme (introduced by the two string instruments). The slow movement is magical, sounding from the outset quite like a Schubert song in which the cello sings the minor-key melody against the grim staccato of the piano’s accompaniment. In fact, the melody is that of a song, though not one by Schubert. His friend Leopold Sonnleithner said that the tune was taken from a Swedish song named “Se solen sjunker” (See the Sun Setting), which Schubert heard performed by the tenor Isaak Albert Berg in Vienna in 1827. In 1978 the musicologist Manfred Willfort rediscovered the old song and demonstrated that although Schubert did not quote it verbatim, he did draw substantial inspiration from its melody and its slowly treading accompaniment. In the Scherzo, Schubert tightens the proceedings through the imposition of canon—or, in places, merely close imitation that gives the impression of canon without actually being one. The movement’s trio section is startlingly gruff—a rude peasant dance interrupting a ballet of Biedermeier nymphs.

The finale begins so unpretentiously that the listener would never expect that something so substantial lay ahead. But, as the musicologist Jack Westrup observed, “Schubert’s apparently innocent beginnings often turn out to be the signpost for a good deal of less innocent activity.” The music ranges widely through the harmonic spectrum, spending almost no time in the home key of E-flat following the opening bit. We reach the development section, and suddenly, against a background of falling piano chords, the Swedish melody from the slow movement makes an unexpected appearance in the cello—and it resurfaces yet again later. Eventually Schubert switches back to the major mode and zeroes in the conclusion with repetitive, swaggering figures that put one in mind of a Rossini opera.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri “del Gesu”̀ violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

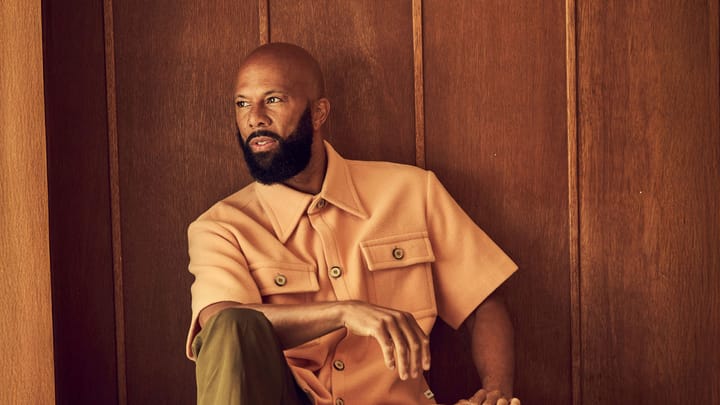

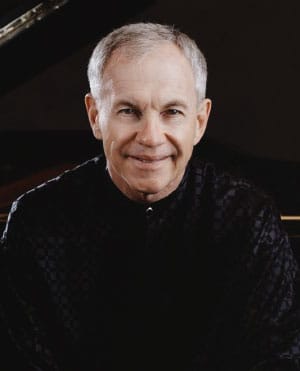

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of last season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.