In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, January 26, 2025, at 2:00pm

Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony

Arnold Bax

Quintet for Oboe and Strings (1922)

Tempo molto moderato

Lento espressivo

Allegro giocoso

Russ de Luna oboe

Dan Carlson violin

Florin Parvulescu violin

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson viola

Davis You cello

Camille Saint-Saëns

Fantaisie in A major, Opus 124 (1907)

Yubeen Kim flute

Katherine Siochi harp

Intermission

Benjamin Britten

Two Pieces (1929)

Un poco andante

Allegro con molto moto

Dan Carlson violin

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson viola

Marc Shapiro piano

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Clarinet Quintet in F-sharp minor, Opus 10 (1891)

Allegro moderato

Larghetto affettuoso

Allegro leggiero

Allegro agitato

Yuhsin Galaxy Su clarinet

Polina Sedukh violin

Olivia Chen violin

Katarzyna Bryla viola

Sébastien Gingras cello

Program Notes

Quintet for Oboe and Strings

Arnold Bax

Born: November 8, 1883, in London

Died: October 3, 1953, in Cork, Ireland

Work Composed: 1922

Arnold Bax was born in the South London district of Streatham, but he really came into his own when, inspired by the poetry of W.B. Yeats, he visited the west coast of Ireland in 1902. “The Celt within me stood revealed,” he recalled in his 1943 autobiography, Farewell, My Youth.

His family had grown wealthy from owning a share in the patent for waterproofed mackintosh raincoats, and this affluence enabled him to travel extensively as a young man—to Germany, to Russia, but most often to Ireland. For about 25 years he paid annual visits to the Donegal village of Glencolumbkille, in the far northwest of Ireland. He lived in Dublin from 1911–14, and for a while he adopted the Irish pseudonym Dermot O’Byrne, which graced several collections of poetry and short stores he published. During his lifetime, his music was more widely known in Ireland than in England, but he nonetheless received honors from the government of Great Britain as well as from Irish institutions.

Bax was never at the cutting edge but his scores were invariably well-crafted, reflecting by turns the colorful orchestral palette of Glazunov, the elusive evocations of Debussy, certain modernisms of Stravinsky, and the stern grandeur of Sibelius. He left a corpus of about 40 chamber works for various forces, which stretched from a string quartet in 1903 through to a piano trio in 1946. He wrote his Oboe Quintet in 1923 for the oboist Leon Goossens, to whom it is dedicated and who played in its premiere (on May 11, 1924, at London’s Hyde Park Hotel, with the Kutcher Quartet). Writing in Cobbett’s Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music (1929), the commentator Edwin Evans observed, “Whilst not unduly submissive to the pastoral suggestions which seem inseparable from the oboe, the composer has not resisted them, and the result is a mood which is not merely pastoral, but, in the larger sense, a nature-mood.” The highly chromatic writing conveys a pungent harmonic fragrance that is characteristic of British music of its time (Delius, for example), but the folkish flavor is rarely far away, thanks to modal melodies and, in the finale, sprightly rhythms of an Irish dance. Bax makes full use of the oboe’s range, showing an appreciation for the character of its different registers, and he gives it some rhapsodic passages that have an improvised feel. The string writing is similarly detailed, making use of mutes, ponticello (bowing near the bridge), and pizzicato playing to expand the textural character into something that can verge on the symphonic. Ink has been spilled over the fact that the second theme of the last movement, possibly a variant on the ancient Irish folksong “The Lament of the Sons of Usnach,” has the same contour as a theme found in Brahms’s Fourth Symphony and Charles Villiers Stanford’s Third—which one is inclined to take as signifying nothing.

Fantaisie in A major, Opus 124

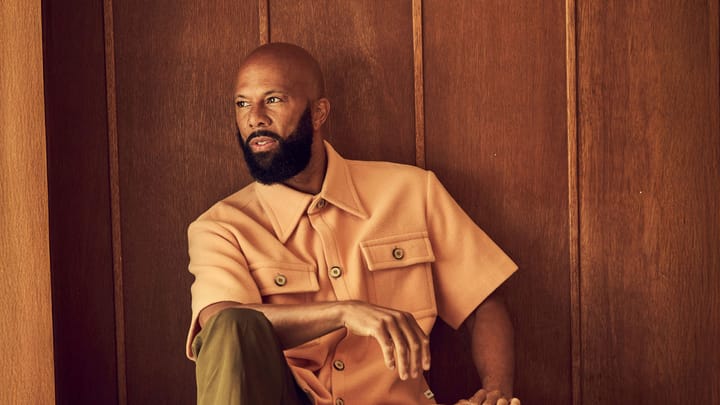

Camille Saint-Saëns

Born: October 9, 1835, in Paris

Died: December 16, 1921, in Algiers

Work Composed: March 1907

At the dawn of the 20th century, Camille Saint-Saëns was settling into his twilight years. Nearly all the pieces for which he is remembered today—far fewer than his impressive catalogue deserves—were distantly behind him, and he was increasingly viewed as a dinosaur. He had acknowledged that status as early as 1886, when he unveiled (privately) his Carnival of the Animals, quoting his Danse macabre in the movement pointedly titled “Fossils.” In 1907, a statue of Saint-Saëns, score on lap, was installed in the commune of Dieppe, even though French law forbade erecting monuments to living persons. “Since one only puts up statues to the dead,” he remarked at its inauguration, “it follows that I am now counted among their number. You will excuse me therefore from making a speech.”

But inspiration still flowed, yielding two 20th-century decades of orchestral and chamber compositions, operas, choral works, piano pieces, organ solos, and songs. His late chamber music veers toward spare refinement that culminates in the sonatas of his final year—for oboe, clarinet, and bassoon. This tendency informs the Fantaisie, played here not in its original setting for violin and harp but rather in a transcription for flute and harp, the recasting made possible by transposing some octaves and reducing the violin’s double-stops.

Saint-Saëns wrote it for the Eissler sisters, Marianne (violin) and Clara (harp), to whom it is dedicated and who premiered it on July 3, 1907, in London. The Fantaisie represents an expansion of an unpublished piano piece, Antwort (Answer), that Saint-Saëns had written in 1866; there he had marked the opening “Allegretto quasi arpa e flauto” (Allegretto, almost like harp and flute)—which provides a strong justification for the flute transcription. The first section (Poco allegretto) has an improvisatory flavor, with the flute’s relaxed lines contrasting with the harp’s arpeggios and glissandos. The second section (Allegro) provides virtuoso writing for the flute. The third (Vivo e grazioso) is buoyant and dance-like, though with five beats per measure. In the final section, the harp repeats a harmonic pattern with a descending ground-bass line, over which the flute plays constant variations; it so much resembles Monteverdi’s Lamento della Ninfa that one wonders if Saint-Saëns had heard that recently at one of Vincent d’Indy’s early-music concerts at the Schola Cantorum in Paris. The Fantaisie concludes (Poco più mosso) with music reminiscent of the opening.

Two Pieces

Benjamin Britten

Born: November 22, 1913, in Lowestoft, England

Died: December 4, 1976, in Aldeburgh, England

Work Composed: 1929

Benjamin Britten studied piano seriously as a child, his adored mother being a pianist and singer, and at the age of 10 took up the viola. When he was 13, he met the noted composer and teacher Frank Bridge, who accepted him as a private composition student. Already at the age of 14 he had completed 100 compositions. “By the time I was 13 or 14,” he recalled in a 1963 newspaper article, “I was beginning to get more adventurous. Before then, what I’d been writing had been sort of early 19th century in style; and then I heard Holst’s ‘Planets’ and Ravel’s string quartet and was excited by them. I started writing in a much freer harmonic idiom.”

In 1930 Britten entered London’s Royal College of Music, where composer John Ireland and pianists Arthur Benjamin and Harold Samuel refined his musicianship. He still worked on the side with Bridge, who steered him to up-to-date developments in scores by Mahler, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky. In 1935 he published the works that bear his first opus numbers: his Sinfonietta and his Phantasy Oboe Quartet. But what of all those pieces he wrote before he started assigning opus numbers? They didn’t go into his “mature” catalogue, to be sure, but some were worthy compositions. Eight of them live on in his Simple Symphony, a much-performed piece he created in 1933–34 as a four-movement orchestral work expanded from songs and piano pieces he had written as a precocious youngster, between 1923 and 1926.

In conjunction with the 2013 celebration of the centennial of Britten’s birth, the publisher Faber Music combed through the composer’s unpublished works and brought a number of them into print. In 1964, Britten had been instrumental in founding that division of Faber & Faber book publishers, having acrimoniously terminated his earlier relationships with Oxford University Press and Boosey & Hawkes, which dominated British music publishing. Although they qualify as juvenilia, these short movements from late 1929, the work of a 16-year-old still at boarding school, reveal a brave musical imagination. The first movement has a rhapsodic cast, its tempo fluctuating as the piece unrolls, its perfumed harmony reminiscent of Scriabin, its ethereal sound enhanced by the violin and viola playing with mutes. The second is a more forthright scherzo. These are almost surely the forward-looking pieces Britten was referring to when he wrote to his parents in January 1930, reporting on an encounter with his school’s conservative music teacher, who had asked if he had written anything that could be played in a school concert: “I thrust the nicer modern one into his hands—but he nearly choked & so I had to show him the silly small one, and he even calls that one modern!!!”

Clarinet Quintet in F-sharp minor, Opus 10

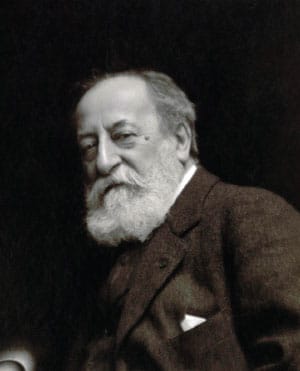

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Born: August 15, 1875, in London

Died: September 1, 1912, in London

Work Composed: 1891

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in London to a father from Sierra Leone and a mother from England, who raised him as a single parent after the father returned to Africa. Coleridge-Taylor entered the Royal College of Music as a violinist in 1890 and wrote an accomplished Te Deum setting the same year. He composed prolifically, at first producing a stream of chamber music, much of it redolent of Brahms. At the age of 17 he became impassioned by the music of Dvořák, and this motivated him to explore American and African-American music, which Dvořák promoted. In 1898, he composed the cantata Scenes from “The Song of Hiawatha,” portions of which became famous.

Coleridge-Taylor was also an admired conductor, leading the Westmoreland Festival from 1901 to 1904 and London’s Handel Society from then until his death. He taught composition at Trinity College of Music and the Guildhall School of Music. He encountered many luminaries of African-American culture when they passed through England, and Coleridge-Taylor made three visits to the United States, in 1904, 1906, and 1910.

He produced a large catalogue of compositions for a composer who lived only two weeks beyond his 37th birthday, when he was felled by pneumonia. The 1890s was his decade for chamber music; still a student, he wrote in quick succession his Piano Quintet, Nonet, Piano Trio, Fantasiestücke for String Quartet, Clarinet Quintet, and String Quartet (now lost). Brahms was the “grand old man” of chamber music, his final chamber work being his Clarinet Quintet, composed and premiered in 1891. After it was played in London, Charles Villiers Stanford observed how difficult it would be for any composer to write a similarly scored composition in the shadow of such a model. Not to be deterred, Coleridge-Taylor promptly composed his Clarinet Quintet and presented it to Stanford, who took it with him on an 1897 trip to Berlin. There he shared it with Brahms’s friend Joseph Joachim, who played it privately with colleagues and spoke of it enthusiastically. Brahms’s autumnal Romanticism may transmit a slight touch on this work, but stronger influence is derived from Dvořák. In Coleridge-Taylor’s Clarinet Quintet, we spy Dvořákian melodic turns of a folkish bent—the opening themes of the first, second, and fourth movements, for example—and harmonies that can veer modal. We often think of Dvořák as an inspiration for African-American composers of the early 20th century, but here we are reminded of his similar influence on a remarkable Anglo-African composer.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Russ de Luna joined the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra as English Horn in 2007 and holds the Joseph & Pauline Scafidi Chair. He appeared as soloist with the Orchestra in the US premiere of Outi Tarkiainen’s Milky Ways, and was previously featured in Aaron Copland’s Quiet City and Jean Sibelius’s The Swan of Tuonela. He has also performed with the Atlanta Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, and New York Philharmonic. A graduate of Boston University and Northwestern University, he teaches at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and coaches the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra.

Dan Carlson joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2006. He currently serves as Principal Second Violin, occupying the Dinner & Swig Families Chair. He previously served as rotating concertmaster for the New World Symphony and he has made solo appearances with the Phoenix Symphony, Chicago String Ensemble, New World Symphony, and the Prometheus Chamber Orchestra. A graduate of the Juilliard School, he has performed chamber music extensively throughout New York.

Florin Parvulescu joined the San Francisco Symphony first violins in 1998. A native of Romania, he was previously a member of the St. Louis Symphony and Baltimore Symphony, won the 1993 Marbury Competition at the Peabody Conservatory, and was a prizewinner in the 1994 Yale Gordon Concerto Competition. He also attended the American Academy of Conducting at the Aspen Music Festival.

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section in 2022. Previously a member of the St. Louis Symphony, he is a laureate of multiple competitions, most recently the Primrose International Viola Competition, and has participated in the Yellow Barn, Ravinia, and AIMS festivals. Born in Russia, he graduated from New England Conservatory, where he won the concerto competition. (Learn more about Plashinov-Johnson in his Meet the Musicians interview.)

Davis You joined the San Francisco Symphony cello section at the beginning of the 2024–25 season and holds the Lyman & Carol Casey Second Century Chair. He recently received his bachelor of music from New England Conservatory, where he studied with Laurence Lesser and Paul Katz, and regularly appeared as principal cello of the NEC Philharmonia. He was a member of Quartet Luminera, which won the silver medal at the Fischoff National Chamber Music Competition. A Bay Area native, You began his cello studies with Irene Sharp and Jonathan Koh.

Yubeen Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Flute in January 2024 and holds the Caroline H. Hume Chair. He was previously principal flute of the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra and has frequently played as guest principal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He won first prize at the 2022 ARD International Music Competition and 2015 Prague Spring International Music Competition and won multiple prizes at the 2014 Concours de Genève. He studied at the Lyon Conservatory, Paris Conservatory, and the Hanns Eisler School of Music Berlin.

Katherine Siochi joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Harp beginning in the 2023–24 season. She was previously principal harp of the Minnesota Orchestra, Kansas City Symphony, and Sarasota Orchestra, and has appeared as a guest with the Chicago Symphony and New York Philharmonic. She was the gold medalist of the 2016 USA International Harp Competition and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Marc Shapiro is Principal Keyboard of the California Symphony and from 1984 to 2003 was the San Francisco Symphony Chorus accompanist. He performs frequently with Chamber Music Sundaes, Sierra Chamber Music Society, Mainly Mozart Festival, and the Mohonk Festival.

Yuhsin Galaxy Su joined the San Francisco Symphony as Second Clarinet at the beginning of the 2024–25 season. She recently completed a master’s degree at the Colburn School, where she studied with Yehuda Gilad, and before that studied at the Curtis Institute of Music with Anthony McGill. She won top prizes in the 2013 and ’14 HSNU concerto competitions, third prize and audience prize at the International Morningside Music Bridge in Canada, first prize at the Young Classical Virtuoso of Tomorrow Music Competition, and two Chimei Arts Awards.

Polina Sedukh, a native of Saint Petersburg, Russia, joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2007. She was previously a member of the Boston Symphony and made her solo debut with the Chamber Orchestra of Liepaya in Latvia at the age of seven, followed by recital tours in the United States, Germany, and Austria.

Olivia Chen joined the San Francisco Symphony’s second violin section at the beginning of the 2023–24 season and is currently Acting Assistant Principal. She was a Tanglewood fellow for two summers, serving as concertmaster of the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra. She has also performed with the New York String Orchestra at Carnegie Hall and with the Baltimore Symphony. Chen pursued her undergraduate studies at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, where she won the Marbury Violin Competition, Melissa Tiller Violin Prize, and Sidney Friedberg Prize.

Katarzyna Bryla joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section beginning with the 2022–23 season. She was born into a family of musicians and has earned more than two dozen awards in the United States, France, and her native Poland. In 2019 she became a coprincipal violist of Orchestra of St. Luke’s and has also been a member of the New York City Ballet Orchestra and the New York Pops.

Sébastien Gingras holds the Penelope Clark Second Century Chair and joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2010 after being a member of the New World Symphony and the St. Louis Symphony. He grew up in Chicoutimi, Québec, where he was educated at the Conservatoire de Musique. After graduating, he moved to Boston to study at New England Conservatory, where he received his master’s degree. He has participated in the Ravinia Festival’s Steans Institute and Yellow Barn.