In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, March 16, 2025, at 2:00pm

Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony

Jeremiah Siochi

Pelagic Poem (2025)

World Premiere

Katherine Siochi harp

Jacob Nissly vibraphone

Gustav Mahler

Piano Quartet in A minor (ca. 1866)

Nicht zu schnell–Mit Leidenschaft (Not too fast–With passion)

Florin Parvulescu violin

Yun Jie Liu viola

David Goldblatt cello

Samantha Cho piano

Dmitri Shostakovich

arr. Atovmyan

Five Pieces (ca. 1970)

Prelude

Gavotte

Elegy

Waltz

Polka

Yubeen Kim flute

Jeein Kim violin

Yuhsin Galaxy Su piano

Intermission

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493 (1786)

Allegro molto moderato

Andante un poco moto

Scherzo

Allegro assai

Jessie Fellows violin

Katie Kadarauch viola

Anne Richardson cello

Yuhsin Galaxy Su piano

Program Notes

Pelagic Poem

Jeremiah Siochi

Born: April 19, 1992, in Zanesville, Ohio

Work Composed: 2025

Composer and songwriter Jeremiah Siochi draws inspiration from the classical tradition as well as from jazz, folk, and pop, producing scores that combine visceral rhythms and melodies with experimental elements. He earned a bachelor of science degree in electrical and computer engineering at Duke University, and while a student there he also studied composition with two noted composers on the school’s music faculty, Stephen Jaffe and Scott Lindroth. His music has been performed internationally and has been featured on National Public Radio. He works as a software developer by day and at night writes songs, electronic music, and chamber works.

In 2016 Siochi won the 5th Solo Harp Composition Contest of the USA International Harp Competition for his Sublimation, which was then published by Lyon & Healy, the company at the center of the American harp community. “The most interesting aspect of the piece, to me, is the way it displays two different qualities of the harp—one that is percussive and rhythmic and one that is melodic and lyrical,” he said in an interview with Harp Column. “I wanted to make [the percussive] element the focal point of the work, almost treating the harp as a drum and establishing a rhythmic groove before even the suggestion of melody or harmony appears. . . . Since I’m coming from a classical piano background growing up, that’s my default stance when I approach new music and I have to consciously pull away from that pianistic impulse and really consider the strengths and limitations of the instrument I’m composing for.”

He has provided this comment about Pelagic Poem for harp and vibraphone, which receives its world premiere in this concert:

This work emerged from collaborating with my sister, the harpist Katherine Siochi, who has always been very supportive of my composition efforts for harp and is the reason the majority of my solo and chamber works feature the harp. I am extremely grateful to her for helping me workshop many musical ideas and sketches over the years. Because the harp is a less frequently used instrument in chamber works, I was very excited for the opportunity to contribute a new piece for an unusual pairing—harp and vibraphone. This piece emphasizes both the similarities and differences between the two instruments. While the vibraphone is typically thought of as a percussion instrument and the harp as traditionally a lyrical and flowing one, which my work certainly leans into, the vibraphone can play a lyrical and singing role, just as the harp is capable of dancing rhythms and percussive strikes.

The piece itself is built around several short, plainly-stated motifs, and is composed of two contrasting halves. The first has an overall drier, rhythmic, and even turbulent character that includes a fugue-like episode building to the halfway mark. While still thematically connected, the second half flips this on its head—literally—by inverting each of the original motifs: what went up now goes down, and vice versa. The tone of this section is much more flowing, water-like, and sustained, with less emphasis on fast-moving rhythms. As a whole, I focus on the interplay between the two instruments across various musical aspects—melodic, harmonic, timbral, and rhythmic interactions. Syncopation and groups of seven beats are central, and I tend to draw harmonic inspiration from jazz, which seems rather fitting given the vibraphone’s importance to the genre.

Piano Quartet in A minor

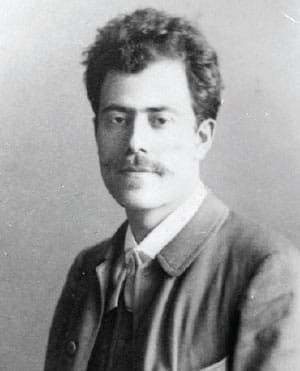

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1876–77

Gustav Mahler occupies a singular niche in music history thanks to his achievements in symphonies, art songs, and orchestral song cycles. Chamber music was not among his concerns as a mature composer, but it did occupy him in his formative years, when he produced several specimens. In the course of his study at the Vienna Conservatory (which began in 1875) he “switched his major” from piano to composition. In June 1876 he won first prize in the Conservatory’s piano competition and a week later his “First Movement from a Quintet” (now lost) was one of two entries to tie for a first prize in composition.

What we know about the Piano Quartet movement is that its manuscript, which resides in the Morgan Library in New York, came to light after the death of the composer’s widow, Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel (who was sequentially married to a composer, an architect, and a novelist). It was among her effects in a folder titled “Youthful Works,” which it shared with a couple of Mahler’s fragmentary song-settings and some sketches for his First Symphony. The date 1876 was inscribed at the bottom of the title page, though it was quite clearly added at a later date.

Some years later, Mahler spoke about his conservatory days with his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner. He told her that he did not complete a single work there, usually abandoning them after he had finished just a movement or two. “It was not only that I was impatient to begin a new piece,” he explained, “but rather that before I finished my work it no longer challenged or interested me, as I had gone beyond it. But who at the time could know whether my trouble was not a lack of ability or of the power to persevere?” He also told her, “The best among them was a Piano Quartet, which belonged to the end of the four-year stint at the Conservatory and which was very warmly received.”

The fact that the Piano Quartet consists only of an opening movement largely mandated that it could not enter the repertoire. (Mahler did write out a 25-measure sketch for a scherzo movement in 6/8 meter for piano quartet, but it’s unclear whether they were intended for the same piece.)

What we have here is a very accomplished student work—one, indeed, that any student should have been proud to write. It demonstrates that the 16-year-old Mahler possessed a firm grasp of how to put an 11-minute (or so) piece together using time-honored traditions of musical structure. The three-note motif heard in the bass part of the piano at the beginning serves as glue to lend cohesion, and the subsidiary themes are perfectly fine. The generally Brahmsian musical language reflects a sort of common currency to which a Vienna Conservatory student would have been most strenuously exposed at that time. A listener will search in vain for anything that really sounds like what we think of as Mahlerian, although the odd violin cadenza near the end, marked ungemein rubato und leidenschaftlich (extremely rubato and passionate), certainly counts as an outburst, and Mahler would later become noted for musical outbursts. It’s a pity he didn’t finish his Piano Quartet, but the single movement he did bring to fruition fully deserves an occasional hearing for both its musical content and its historical importance at the beginning of a remarkable career.

Prelude from Five Pieces

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg

Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1955, arranged 1970

When listeners think of Dmitri Shostakovich, they are likely to envision a composer whose music is as close as music gets to bipolar, ricocheting from unbridled euphoria to despondency and terror, often settling on the latter. Such music is often encountered in the composer’s symphonies and string quartets, but the Five Pieces are not that kind of music. They aspire only to entertain, to elicit a nod of agreeable connection, to prompt a welcome smile. The movements trace their ancestry to scores Shostakovich originally composed for film, ballet, and theater productions, with one questionable exception. But although he invented all the music, the performance as presented here is twice removed from the composer.

The recasting of the Five Pieces from their original versions was done by Shostakovich’s friend Levon Atovmyan (1901–73), a Turkmen composer, arranger, and man-about-the-music-industry. In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, Atovmyan created many composer-approved suites comprising movements from assorted Shostakovich works, including the four Ballet Suites and the suites from the film scores for The Gadfly (1955) and Hamlet (1932). Atovmyan apparently assembled the Five Pieces by 1970, and they were published under the rubric Five Pieces for Two Violins and Piano. The parts can also be played by flute, violin, and piano, and that is how the set is performed in this concert—an adaptation of an arrangement of original movements by Shostakovich.

The Prelude derives from Shostakovich’s music for The Gadfly, where it is titled “Guitars” and was to be played by two guitars. Atovmyan had already transcribed this movement in his orchestral Suite from The Gadfly (Opus 78a), in which guise it may be familiar to some listeners. In that setting, he mixed in some music from a separate Gadfly section, but in the Five Pieces he reverts to the text Shostakovich originally wrote (though with bowed strings instead of plucked ones). It balances on the thin boundary between pensive Russian melancholy and genial Viennese good cheer. The flute and violin track each other almost always in the same rhythm, though in harmony, a characteristic that maintains for nearly the entire suite.

The Gavotte and the Elegy are both taken from Shostakovich’s incidental music for a production of the play The Human Comedy, based on episodes from Balzac’s novels; the play was introduced in 1934 at Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theatre. The Gavotte (a French courtly dance), is a lighthearted movement, here one that chuckles and perhaps even hiccups; and the Elegy assumes a pose of unruffled peacefulness. Atomyan used orchestral settings of both of these movements in the 1951 Ballet Suite No. 3.

The Waltz robes the flowing dance in a lightly mournful, minor-key sensibility so often encountered in Russian light music. This movement’s source remains a mystery, but this music does appear in a collection called Shostakovich: Easy Pieces for the Piano, issued by publisher G. Schirmer; that volume does not identify the source. It may possibly have been an original composition by Atovmyan.

The set concludes with a giddy Polka, which originated in the 1935 comedy-ballet The Limpid Stream, where it appears as the “Dance of the Milkmaid and the Tractor Driver.” Atovmyan also used it in the Ballet Suite No. 1 (published in 1949). Aficionados of song recitals may join me in believing that William Bolcom must have had this polka on his mind when he composed his evergreen encore “Lime Jello Marshmallow Cottage Cheese Surprise.”

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1786

Franz Anton Hoffmeister had high hopes when he commissioned Mozart to write three piano quartets in 1785, but things didn’t go as planned. According to Mozart’s biographer Georg Nicolaus von Nissen, “Mozart’s first piano quartet, in G minor, was thought so little of at first that the publisher Hoffmeister gave the master the advance portion of the honorarium on the condition that he not compose the other two agreed-upon quartets and that Hoffmeister should be released from his contract.”

Yes, you read that right: Nissen said that Hoffmeister paid Mozart to not write any more piano quartets than the one he had already finished. Although this recollection may be accurate in spirit, it seems to be slightly off in factual accuracy. It seems that by the time this arrangement was proposed, Mozart—thank heavens!—must have already gone on to complete the second of the three projected works, his Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K.493. He entered it on June 3, 1786, in the catalogue he kept of his musical compositions, immediately following his opera Le nozze di Figaro. When the E-flat–major piano quartet was published the next year, by the rival firm of Artaria, that company seems to have printed the piano, viola, and cello parts from plates it had purchased from Hoffmeister. That’s a strong indictment, since it suggests that Hoffmeister decided to withdraw from the project even if it meant sacrificing a good deal of nuts-and-bolts work that had already been expended on an edition. Artaria also made no money from the venture, and the third piano quartet was never written. In June 1788, the Journal des Luxus und der Moden pointed to the problem: it was too difficult for amateurs. “Many another piece keeps some countenance, even when indifferently performed; but in truth one can hardly bear listening to this product of Mozart’s when it falls into mediocre amateurish hands and is negligently played.”

One senses a dreamy quality in the opening movement, nowhere more than in the surprising modulation that heralds the development section. The melody at that point is a motif that pervades this movement, a figure that begins with a falling sixth, first heard as the second theme of the exposition. In the course of the movement, it is transposed to many keys and is heard in various instrumental combinations; at the very end, it even overlaps with itself in a bit of contrapuntal imitation. Where the G-minor piano quartet is taut and tense, the one in E-flat major tends towards luxuriance, which reaches its peak in the Larghetto. This is one of Mozart’s most eloquent slow movements, so rich in reiterations that it truly seems a conversation among the four participants.

Mozart had second thoughts about how to conclude this piece. He sketched out some delightful material that he decided not to follow through with; like the finale he did end up composing, it begins with a half-measure’s upbeat. The finale as it stands is essentially a rondo, but Mozart grafts onto it aspects of a sonata structure as well. A second principal theme, replete with a touch of characterful syncopation, follows the initial rondo melody, and later a blustery minor-mode passage, sounding ever so much like a development section, provides an occasion for the pianist to sweep up and down the keyboard with impressively virtuosic figuration while pursuing harmonic modulations. Throughout this movement, we find Mozart practically on the verge of a piano concerto, with the piano “soloist” and the strings operating in the back-and-forth contrast found in a concerto more than in the integrated style more typical of chamber music.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Katherine Siochi joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Harp beginning in the 2023–24 season. She was previously principal harp of the Minnesota Orchestra, Kansas City Symphony, and Sarasota Orchestra, and has appeared as a guest with the Chicago Symphony and New York Philharmonic. She was the gold medalist of the 2016 USA International Harp Competition and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Jacob Nissly joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Percussion in 2013 and is also chair of the percussion department at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Previously, he was principal percussion of the Cleveland Orchestra and the Detroit Symphony. In 2019, Nissly premiered Adam Schoenberg’s percussion concerto Losing Earth with the SF Symphony, and has also performed it with the New Zealand Symphony and Omaha Symphony. He holds a bachelor of music from Northwestern University and a master’s degree from the Juilliard School.

Florin Parvulescu joined the San Francisco Symphony first violins in 1998. A native of Romania, he was previously a member of the St. Louis Symphony and Baltimore Symphony, won the 1993 Marbury Competition at the Peabody Conservatory, and was a prizewinner in the 1994 Yale Gordon Concerto Competition. He also attended the American Academy of Conducting at the Aspen Music Festival.

Yun Jie Liu is Associate Principal Viola of the San Francisco Symphony, which he joined in 1993. Previously he was a member of the National Symphony in Washington, DC. Born in Shanghai, he studied at the Shanghai Conservatory and was named an assistant professor of viola upon graduation. He now serves on the faculty of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

David Goldblatt joined the San Francisco Symphony cello section in 1978 and holds the Christine & Pierre Lamond Second Century Chair, having previously played in the Pittsburgh Symphony. A graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, he has also performed with the Concerto Soloists of Philadelphia and Santa Fe Opera Orchestra. He is currently a coach for the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra.

Samantha Cho is a professor of piano pedagogy at San Francisco Conservatory of Music and previously served as an associate professor of music at Cabrillo College. She has performed on the San Francisco Symphony’s Lunar New Year Concert as well as on Live from WFMT and the Dame Myra Hess Memorial Concert in Chicago.

Yubeen Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Flute in January 2024 and holds the Caroline H. Hume Chair. He was previously principal flute of the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra and has frequently played as guest principal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He won first prize at the 2022 ARD International Music Competition and 2015 Prague Spring International Music Competition and won multiple prizes at the 2014 Concours de Genève. He studied at the Lyon Conservatory, Paris Conservatory, and the Hanns Eisler School of Music Berlin.

Jeein Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony as Section First Violin at the beginning of the 2024–25 season. She was previously a member of the Korean National Symphony Orchestra and has been a substitute musician with the Chicago Symphony. As a soloist, Kim has performed with Praha Hradec Kralove Philharmonic Orchestra, Yonsei University Orchestra, Prime Philharmonic Orchestra, JK Chamber Orchestra, and Northwest Sinfonietta. She studied at Yale School of Music, New England Conservatory, and Yonsei University, and attended the Taos School of Music, Heifetz Summer Institute, and Norfolk Chamber Music Festival. She has won top prizes at the Menuhin Competition, Seoul International Music Competition, and Northwest Sinfonietta Youth Competition.

Yuhsin Galaxy Su joined the San Francisco Symphony as Second Clarinet at the beginning of the 2024–25 season, and is also an accomplished pianist. She recently completed a master’s degree at the Colburn School, where she studied clarinet with Yehuda Gilad, and before that studied at the Curtis Institute of Music with Anthony McGill. She won top prizes in the 2013 and ’14 HSNU concerto competitions, first prize at the Young Classical Virtuoso of Tomorrow Music Competition, and two Chimei Arts Awards.

Jessie Fellows is Acting Associate Principal Second Violin with the San Francisco Symphony and holds the Audrey Avis Aasen-Hull Chair. Prior to her appointment, she performed frequently with the St. Louis Symphony and New York Philharmonic. Born into a musical family, she began her studies at the age of three under the direction of her mother in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Katie Kadarauch joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2007 as Assistant Principal Viola. A native of the Bay Area, she was principal viola of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra and earned a bachelor’s degree and graduate diploma from the New England Conservatory. She also studied at the Colburn School, during which time she performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and recorded film scores. She plays on a Peter Rombouts viola ca. 1720, on loan from the Symphony.

Anne Richardson joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal Cello at the beginning of the 2024–25 season and holds the Peter & Jacqueline Hoefer Chair. She was previously an academy fellow with the Bavarian Radio Symphony and has performed with the Verbier Festival Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and Pittsburgh Symphony. As a soloist, she has appeared with the Louisville Orchestra and Juilliard Orchestra, and has been featured by Lincoln Center’s Great Performance Circle, the Juilliard in Aiken Festival, and Vail International Dance Festival.