In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, September 29, 2024, at 2:00pm

Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony

Kinan Azmeh

Café Damas (2018)

Jessie Fellows violin

Katarzyna Bryla viola

Orion Miller bass

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Quintet in E-flat major, K.452 (1784)

Largo–Allegro moderato

Larghetto

Rondo: Allegretto

James Button oboe

Matthew Griffith clarinet

Jessica Valeri horn

Justin Cummings bassoon

Julio Elizalde piano

Intermission

Florent Schmitt

Sonatine en trio, Opus 85 (1935)

Assez anime

Assez vif

Tres lent

Anime

Blair Francis Paponiu flute

Matthew Griffith clarinet

Gwendolyn Mok piano

Robert Schumann

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, Opus 47 (1842)

Sostenuto assai–Allegro ma non troppo

(sempre con molto sentimento)

Finale: Vivace

Scherzo: Molto vivace

Andante cantabile

Wyatt Underhill violin

Jonathan Vinocour viola

Sébastien Gingras cello

Julio Elizalde piano

Program Notes

Café Damas

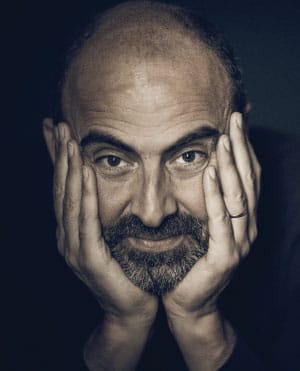

Kinan Azmeh

Born: June 10, 1976, in Damascus, Syria

Work Composed: 2018

Following initial studies on the violin, Kinan Azmeh switched to clarinet at the age of six. After graduating from the Damascus High Institute of Music and Damascus University’s School of Electrical Engineering, he proceeded to study clarinet at the Juilliard School, where he received his master’s degree and graduate diploma. Azmeh is now based in New York, where in 2013 he earned his PhD at the City University of New York.

He was the first Arab musician to win the Nikolai Rubinstein International Youth Competition in Moscow. In 2003, he and four Syrian colleagues formed the Arabic jazz band Hewar, which he describes as “an attempt to transcend the barriers of cultural disparities and misconceptions, and establish a civilized communication which builds on what brings humans closer together.” He is also a member of the Silk Road Ensemble and has appeared with Daniel Barenboim’s West-Eastern Divan Orchestra.

Azmeh has produced a substantial body of compositions in many genres, including solo and chamber pieces, orchestral works, film scores, and music for theater and dance. Café Damas, for violin, cello, and double bass, was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered by three of its musicians in January 2019. Azmeh provided this comment about the piece:

This work is inspired by the idea of an imaginary traditional house band in a 1960s café in Damascus, a band that has not changed personnel nor location for decades and continues to play in spite of all. Musically speaking, this piece enjoys a rather traditional form that opens with a taqasīm (melodic improvisation), which introduces the listener to the maqam (mode) of the composition, followed by a variety of fast modal and rhythmic transformations and solos. Finally, there is a coda that brings back a distant and faded memory of the same imaginary band in that imaginary Damascus café.

Quintet in E-flat major, K.452

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1784

On April 10, 1784, Mozart wrote from his home in Vienna to his father in Salzburg to relay news about his recent triumphs. “The concert I gave in the theater,” he reported, “was most successful. I composed two grand concertos and then a quintet, which called forth the very greatest applause; I myself consider it the best thing I have ever written in my life. It is written for one oboe, one clarinet, one horn, one bassoon, and the pianoforte. How I wish you could have heard it! And how beautifully it was performed! Well, to tell the truth, I was really worn out by the end after playing so much—and it is greatly to my credit that the audience did not in any degree share the fatigue.”

That’s strong praise, indeed—even making allowances for the generosity of self-congratulation. The performance took place on April 1 at the Burgtheater, and it was liberally packed with music, in line with the custom of the day. Symphonies opened and closed the proceedings (most likely a single symphony split in two), surrounding a succession of arias, a keyboard improvisation, two piano concertos, and this quintet. Mozart had signed off on the piece on March 30, which doubtless caused considerable anxiety among the wind players who were scheduled to unveil it only two days later—the more so since the work’s instrumentation was apparently unprecedented. Nonetheless, all parties must have acquitted themselves with distinction to earn the ovation Mozart described.

The piece seems as much descended from the piano concerto as from chamber music. Piano concertos were much on Mozart’s mind, as he wrote four of them around the same time. In those, he sometimes called for woodwinds to interact with the solo piano almost like equal partners. The quintet’s piano part is quite brilliant, much like what one would expect to find in a concerto, and the piano gets the honor of introducing most of the themes as they appear. The instrument’s prominence seems logical, given its broad range and harmonic capabilities compared to the woodwinds; and it’s worth recalling that Mozart was writing for his own use—and he was never inclined to hide his light under a bushel. On the other hand, the quintet is chamber music at heart, and the four woodwinds are kept plenty busy throughout, even if their parts don’t quite rival the piano’s in sheer virtuosity.

Sonatine en trio, Opus 85

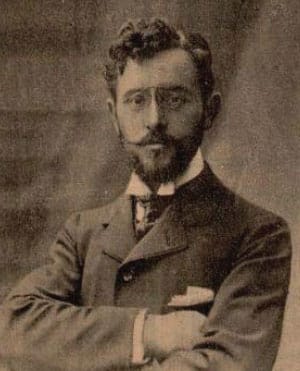

Florent Schmitt

Born: September 28, 1870, in Blâmont, France

Died: August 17, 1958, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

Work Composed: 1934–35

Florent Schmitt’s compositions cover an exceptionally broad range of musical approaches, attitudes, and aspirations. “A leading feature of his work is a strength which sometimes produces violence and even brutality,” reads his entry in Cobbett’s Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music (1929). “On the other hand, the gentler side is not lacking; he can paint tenderness, sorrow, and despair. . . . Above all, he follows no set methods of composition; it is no exaggeration to say that he has a horror of all attempts to fashion ideas according to rule.”

Schmitt was born in Lorraine, in the border region where France abuts Germany, and his music-loving parents fed him a diet of German classics. Nonetheless, he went to school at the Paris Conservatory, where his composition professors included Jules Massenet and Gabriel Fauré. Although he was not a standout pupil, he eventually managed to win the Prix de Rome, a useful stamp of approval for any aspiring French composer.

Some of his pieces were considered bravely avant-garde, and they evoked powerful responses pro and contra, but on the whole he was widely esteemed among French composers. When Paul Dukas died in 1935 and his seat at the Institut de France opened up, Schmitt and Igor Stravinsky were nominated to succeed him. Schmitt beat Stravinsky, 28 votes to 4. His music was slow to penetrate the export market, although critics cheered a number of his scores during an American tour in 1932–33, hailing his Piano Quintet as one of the most impressive of modern chamber pieces.

He was a busy music critic himself, one who expressed himself in writing with the same bluntness he did in conversation. Not everyone appreciated his habit of shouting out his opinions in real time as pieces unrolled at concerts. He was also a virulent antisemite who nurtured a cozy relationship with the Vichy regime during World War II. This could infect his concert outbursts, some of which were so jaw-droppingly offensive that they merit absolute oblivion.

He wrote the Sonatine en trio in 1934–35 for flute, clarinet, and harpsichord (with piano as an accepted substitute), and the following year he prepared a version for violin, cello, and piano. He composed it expressly for the Italian harpsichordist Corradina Mola, an early-music pioneer. She played in its premiere on January 29, 1936, in Paris, and penned a long, flowery description of the four short movements. In the first, the god Pan basks in a clearing beneath dappled light and is joined by gamboling fauns. In the second, Pan is in the woods, hearing the water of a stream ripple over the stones. In the third, a dense forest leads to a dismal pond. And in the fourth, Pan returns to the edge of the forest, where he is bathed in light. “With all his soul, he exhales his joy, his unspeakable new-found bliss.”

Piano Quartet in E-flat major, Opus 47

Robert Schumann

Born: June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony

Died: July 29, 1856, Endenich, near Bonn

Work Composed: 1842

Robert Schumann and his music are so full of surprises that it seems unfair to codify his life and achievements in terms of rehashed truisms. And yet he did characterize his musical personality as the duality of his sub-egos, the fiery Florestan and the dreamy Eusebius, and his music’s emotions can often be broadly reduced to those extremes. And it is also true that Schumann dedicated himself almost exclusively to specific genres for extended periods, exploring their many facets before moving on to mine other lodes. Chamber music occupied him from 1842 until 1847, during which time he produced several works that combined his earlier achievements in piano writing with new discoveries about the art of the string ensemble. From this impetus grew two of chamber music’s greatest masterpieces: his Piano Quintet and Piano Quartet, both written in 1842.

The Piano Quartet begins with a hushed opening of rich chords that shortly give way to a well-measured Allegro and the first broad melody, which is introduced by cello. This is probably not incidental: the work was commissioned by Count Mathieu (or Matvei) Wielhorsky, an accomplished amateur cellist and concert impresario in Saint Petersburg. A Scherzo follows. Though marked Molto vivace, it is hardly buoyant in a Mendelssohn way; a slightly sinister undercurrent emerges here and there throughout the Scherzo proper and its two contrasting trio sections. In the third movement, the cello again emerges to sing one of Schumann’s most sublime melodies, perfect in its balance, soulfulness, and apparent simplicity. The melody is handed off in turn to the violin and then the piano, which applies elegant embellishment. A central section seems almost prayerful and chorale-like, profoundly comforting. The original song melody returns, this time with violin filigree; and at the very end the cellist surreptitiously tunes their lowest string down a step to the otherwise-inaccessible low B-flat, providing a 13-bar pedal-point support for the suspended animation of the movement’s coda. “Alas!,” wrote the Schumann biographer Robert Haven Schauffler 80 years ago, “the long solo which opens the movement, too saccharine in feeling and too mechanical in construction, is the weakest part of the work.” Surely most music-lovers would disagree, and in the strongest terms.

The Eusebius of the Andante cantabile is replaced by Florestan for the Finale, an outpouring of thematic exuberance that grows from a fugue-like opening (and incorporates an episode recalling the Andante’s magical coda). Though finished in November 1842, Schumann’s Piano Quartet did not receive its premiere until two years later, on December 8, 1844, in Leipzig, when it proved successful with the audience. The performance was entrusted to a distinguished group of players: in addition to the cellist Wielhorsky, the ensemble consisted of three accomplished performer-composers—violinist Ferdinand David (who would premiere Mendelssohn’s E-minor Violin Concerto the following year), violist Niels Gade, and Clara Schumann interpreting her husband’s piano part in this work she described as “youthful and fresh.”

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Jessie Fellows is Acting Associate Principal Second Violin with the San Francisco Symphony and holds the Audrey Avis Aasen-Hull Chair. Prior to her appointment, she performed frequently with the St. Louis Symphony and New York Philharmonic. Born into a musical family, she began her studies at the age of three under the direction of her mother in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Katarzyna Bryla joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section beginning with the 2022–23 season. She was born into a family of musicians and has earned more than two dozen awards in the US, France, and her native Poland. In 2019 she became a coprincipal violist of Orchestra of St. Luke’s and has also been a member of the New York City Ballet Orchestra and the New York Pops.

Orion Miller joined the San Francisco Symphony bass section at the beginning of this season. He previously performed with the London Symphony as a Keston Max Fellow, as a substitute musician with the Houston Symphony, and with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in a side-by-side performance at Carnegie Hall. He also served as principal bass for the National Youth Orchestra of the United States and the New York String Orchestra Seminar.

James Button was appointed Associate Principal Oboe of the San Francisco Symphony in September 2017. A native of Australia, he was previously a member of the Nashville Symphony, Santa Fe Opera Orchestra, New World Symphony, and has appeared as guest principal with the Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Melbourne Symphony. His live recording of Jennifer Higdon’s Oboe Concerto with the Nashville Symphony won a Grammy Award in 2018.

Matthew Griffith joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal and E-flat Clarinet at the beginning of the 2022–23 season. He previously served as acting assistant principal clarinet with the North Carolina Symphony and the Nashville Symphony and was a member of TŌN (The Orchestra Now), a graduate-level training orchestra based at Bard College. He has performed as guest soloist with the Boston Pops, Milwaukee Symphony, Ocean City Pops, Eastern Connecticut Symphony, United States Army Field Band, and “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band.

Gwendolyn Mok studied at the Juilliard School, Yale University, and SUNY Stony Brook, and has appeared as a soloist with the London Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, and New York Philharmonic. A regular guest of Symphony Silicon Valley, she is coordinator of keyboard studies at San Jose State University. She has recorded for Nonesuch/Elektra and EMI.

Jessica Valeri joined the San Francisco Symphony horn section in 2008. Prior to her appointment, she was a member of the St. Louis Symphony, Colorado Symphony, Grant Park Orchestra, and Milwaukee Ballet Orchestra. She has also performed with the Milwaukee Symphony, Richmond Symphony, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the International Contemporary Ensemble, and participated in the Grand Teton Music Festival, Lakes Area Music Festival, and Mainly Mozart.

Justin Cummings joined the San Francisco Symphony bassoon section at the beginning of the 2023–24 season. He was previously principal bassoon of the Knoxville Symphony and a fellow of the New World Symphony under Michael Tilson Thomas. He has also performed as a guest with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. He is an alumnus of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Julio Elizalde was born in the Bay Area and received a bachelor’s degree from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music before earning master’s and doctoral degrees from the Juilliard School. He is artistic director of the Olympic Music Festival in Washington, a founding member of the Fischoff-winning New Trio, and tours internationally with violinists Sarah Chang and Ray Chen.

Blair Francis Paponiu joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal Flute, holding the Catherine & Russell Clark Chair, at the beginning of the 2023–24 season. She was previously assistant principal and second flute with the Naples Philharmonic in Florida and performed with the New York Philharmonic for two seasons. She has also been a member of the Austin Symphony and has performed with the Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, and Oregon Symphony.

Wyatt Underhill joined the San Francisco Symphony as Assistant Concertmaster in 2018 and is currently Acting Associate Concertmaster, holding the San Francisco Symphony Foundation Chair. He was previously assistant concertmaster of the Baltimore Symphony, substitute concertmaster with the New Haven Symphony, and associate concertmaster of Symphony in C. He was the founding first violinist of the Blue Hill String Quartet and was a top prizewinner in the Irving M. Klein International Competition for Strings.

Jonathan Vinocour joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Viola in 2009 and was previously principal viola of the St. Louis Symphony and guest principal of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and Chicago Symphony. He has frequently soloed with the SF Symphony and has also played concertos with the St. Louis Symphony, La Jolla Music Society, Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra, and New World Symphony. He serves on the faculty of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music as well as the Aspen Music Festival and School. He plays on a 1784 Lorenzo Storioni viola on loan from the SF Symphony.

Sébastien Gingras holds the Penelope Clark Second Century Chair and joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2010 after being a member of the New World Symphony and the St. Louis Symphony. He grew up in Chicoutimi, Québec, where he was educated at the Conservatoire de Musique. After graduating, he moved to Boston to study at New England Conservatory, where he received his master’s degree. He has participated in the Ravinia Festival’s Steans Institute and Yellow Barn.