In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, October 27, 2024, at 7:30pm

Emanuel Ax piano

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-flat major, Opus 27, no.1, Quasi una fantasia (1801)

Andante–Allegro–Andante

Allegro molto e vivace

Adagio con espressione

Allegro vivace

Arnold Schoenberg

Drei Klavierstücke, Opus 11 (1909)

Mässige Viertel (Moderate ♩)

Mässige Achtel (Moderate ♪)

Bewegte Achtel (With motion ♪)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Opus 27, no.2, Moonlight (1801)

Adagio sostenuto

Allegretto

Presto agitato

Intermission

Arnold Schoenberg

Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, Opus 19 (1911)

Leicht, zart (Light, delicately)

Langsam (Slowly)

Sehr langsam (Very slowly)

Rasch, aber leicht (Fast, but light)

Etwas rasch (Somewhat fast)

Sehr langsam (Very slowly)

Robert Schumann

Fantasy in C major, Opus 17 (1836)

With fantasy and passion throughout

In moderate tempo. Energetically throughout

Slow and sustained. Quiet throughout

Presenting Sponsor of the Great Performers Series

Concert Sponsor

In 1926, Standard Oil of California, now Chevron, donated $10,000 to the San Francisco Symphony, becoming the Symphony’s inaugural partner and one of the first corporate donors to the arts in the United States. In appreciation of the contribution, the Symphony granted the radio broadcast rights to that season’s concerts, kicking off The Standard Hour, the first network broadcast of symphonic music on the West Coast, which would run until 1954.

With the San Francisco Symphony’s Centennial in 2011, Chevron became an Official Second Century Partner, reflecting the highest level of corporate leadership at the Symphony with multi-year funding for core educational programs and concert series, such as Adventures in Music, Music for Families, and the Great Performers Series.

The San Francisco Symphony is deeply grateful to Chevron for their loyalty and support for nearly a century. We look forward to working together to serve and uplift our community through music.

Program Notes

Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-flat major, Opus 27, no.1, Quasi una fantasia

Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Opus 27, no.2, Moonlight

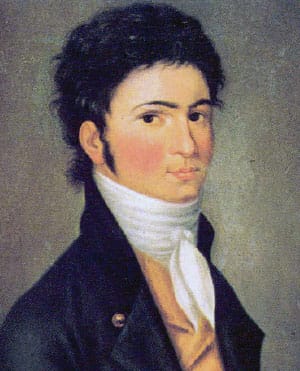

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Works Composed: 1801

In the year 1800, Ludwig van Beethoven completed the 11th of his 32 canonical piano sonatas. Notwithstanding their exorbitant variety, those 11 all unrolled in either three or four separate movements, their first movements invariably cast in sonata form, one of the great triumphs of the Classical era, a three-section structure (exposition, development, recapitulation) that generated security, balance, and drama. Having earned his Classical bona fides, he set out to do something very different in his next three sonatas. Sonata No. 12 opens instead with a set of variations, and then Sonatas Nos. 13 and 14 break the bonds of Classical architecture still further, pouring forth in streams of contrasting ideas.

Beethoven gave them both the same title in musically fashionable Italian: Sonata quasi una fantasia (Sonata Almost Like a Fantasy). Music aficionados at that time would have recognized sonata and fantasy as distinct genres. Sonatas were multi-movement pieces cast in a relatively formal structure, worked out in detail with carefully etched themes woven into the work as unifying elements. Fantasies were single-movement pieces made up of distinct, independent episodes, their themes designed more to evoke fleeting emotive responses than to be developed into balanced structures, the whole being created extemporaneously or at least having an improvisatory flavor. The music theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch explained in his 1802 Musical Dictionary that, in a fantasy, a musician is bound “neither to maintaining a consistent meter nor adhering to a particular character, but rather presents his sequence of ideas through melodies that are sometimes connected precisely or sometimes strung together loosely.”

Beethoven composed both of the Opus 27 sonatas in 1801. He did not write them on commission from anyone, but they did carry dedications when they were published in March 1802—as separate items rather than bundled into a single volume. The first was dedicated to Princess Josephine von Liechtenstein and the second to Countess Giulietta (Julia) Guicciardi, who both frequented salons at which the composer played. He apparently had an unreciprocated crush on the latter.

We may choose to hear Sonata No. 13 as being in four connected movements (à la sonata) or in one free-flowing movement (à la fantasy). If four, the first movement consists of an Andante introduction followed by a brief romp of an Allegro and then a return to the Andante—so a three-part structure but definitely not a sonata form. The second movement would be a scherzo-and-trio, the third a short but contemplative slow movement, and the fourth a very fast and imposing finale that accelerates from Allegro vivace to a Presto coda (those two bits being separated by a reminiscence of the slow movement) and escalates emotions along with the tempo. And yet, this is such a willfully eccentric piece that one may reasonably prefer to consider it a single onrushing conception, more fantasy than sonata.

It is far overshadowed by Sonata No. 14, the Moonlight Sonata. The nickname seems to have come from Ludwig Rellstab’s 1823 novella Theodore: A Musical Sketch. Writing about what he calls “the Adagio from the Fantasia in C-sharp minor,” he proposes this scene: “The lake rests quiet under the light of the moon at twilight; the wave thuds against the dark bank; gloomy wooded mountains rise up and divide this sacred region from the world; swans move through the water with whispering rustle, like spirits, and an Aeolian harp makes its complaints of longing, lonely love mysteriously from the ruin.” Rellstab traveled in 1825 from his home in Berlin to Vienna expressly to meet the revered composer, who received him on multiple occasions. If Rellstab shared his description with Beethoven, we have no record of the composer’s reaction. The lunar allusion was soon picked up by others, and within a few years after Beethoven’s death the epithet Moonlight Sonata became common, although commentators also associated the opening movement’s mood with night-time, death, and mourning. The pianist-composer Carl Czerny suggested this in his 1839 treatise On the Proper Performance of all Beethoven’s Works for Piano Solo: “It is a night scene, in which the voice of a complaining spirit is heard at a distance.”

If moonlight or Aeolian harps or ghostly voices say something about the first movement, they certainly don’t inform the second or third. Beethoven instructs in the score that the second movement is to follow the first without a break, as in Sonata No. 13, but he does not enter such a notation between the second and third, which have normal separation. The second movement is a brief, insouciant scherzo-with-trio (not too fast, at just Allegretto). Franz Liszt called it “a flower between two chasms,” which rings about right given the impetuous outbursts of the concluding movement, which is rich in fiery rising arpeggios and powerfully accented chords.

—James M. Keller

Drei Klavierstücke, Opus 11 Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, Opus 19

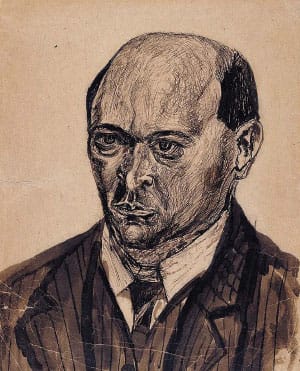

Arnold Schoenberg

Born: September 13, 1874, in Vienna

Died: July 13, 1951, in Los Angeles

Works Composed: 1909, 1911

Schoenberg’s Opus 11 and Opus 19 piano pieces were written at a key moment in his transformation from a late Romantic follower of Gustav Mahler into a leading atonalist who sparked some of the more unpopular musical trends of the 20th century. In 1899 he was still writing lush, tonal pieces like the string sextet Verklärte Nacht, but by the mid-1920s had developed his 12-tone technique, which systematized the banishment of familiar keys and harmony. In between, he composed a series of transitional, freely atonal works—these followed no particular rulebook, only the fractured contours he could dream up on his own.

Many listeners, then and now, have found these works baffling, even incomprehensible. But they’re highly expressive, at least within a rather narrow range of of angst and languor. A century of scholarship has emphasized Schoenberg’s work as a kind of techical advancement—as if atonality could impose scientific rigor and rationality on the mushy human practice of music making. But in the beginning, atonality was all about the opposite—unleashing the subconscious, embracing the weirdness of free association. Think Freud more than Einstein.

Schoenberg (or Schönberg, as he spelled it before immigrating to the United States) hoped his Drei Klavierstücke (Three Piano Pieces) would be premiered by another innovative composer and pianist: Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924). In contrast with Schoenberg’s growing asceticism, Busoni was drawn towards grand spectacle in his own music. Still, Schoenberg saw him as an ally and potential collaborator “whose sympathies lie on the side of all those who are seeking . . . That is why I am turning to you.”

Busoni agreed to play the pieces, but then took it upon himself to rewrite one of them in his own flamboyant style. Schoenberg was incensed, answering, “my piano writing is not the result of any lack of ability, but the expression of a firm will, of specific inclinations, of clearly graspable feelings. What it does not do, is not what it cannot, but what it does not want to do.” He said goodbye to Busoni and gave the pieces to Eta Werndorff, who premiered them in Vienna on January 14, 1910.

Schoenberg wrote five of the Sechs kleine Klavierstücke (Six Little Piano Pieces) in a single day: February 19, 1911. This feat is only a little less impressive when you see each piece is just a single page. But they’re packed with details and subtle inflections—and Schoenberg insisted that they be played with a sense of spaciousness, the performer not overemphasizing their minuteness. He added the sixth piece the following August, and though it doesn’t carry a dedication, Schoenberg’s friends heard it as a memorial for Mahler, who died earlier that summer.

The set was premiered by Louis Closson (a student of Busoni) on February 4, 1912, in Berlin. Later that year, an anonymous Viennese critic described: “Intensity of expression is present in Schönberg’s music to a white-hot degree. In the six piano pieces, snapshots of extraordinary, fast changing states of mind, the extremely compact brevity contributes significantly to the artistic effect, to the intensity of expression.”

— Benjamin Pesetsky

Fantasy in C major, Opus 17

Robert Schumann

Born: June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony

Died: July 29, 1856, Endenich, near Bonn

Work Composed: 1836

Robert Schumann produced his Fantasy in C major during a period when his piano teacher, Friedrich Wieck, was trying in vain to squash the romantic involvement of his daughter, Clara, with Schumann. In January 1836, Wieck sent Clara off to Dresden, and Robert tried to reconcile himself to this severance by having a short-lived affair with another young woman. He later revealed to Clara, in a letter on March 18, 1838, that “the first movement is the most passionate thing I have ever composed—a deep lament for you,” and on April 22, 1839, he wrote to her, “In order to understand the Fantasie you will have to transport yourself into the unhappy summer of 1836, when I renounced you.”

That piece of Summer 1836 was apparently only the first movement of the eventual Fantasy, and at that point Schumann attached to it the title Ruines (Ruins). That autumn he added two further movements, thinking he would donate the proceeds from the three-movement work’s sales to a Beethoven monument project in Bonn. In that form, he advised a publisher, it would have appeared under the title Ruinen. Trophaeen. Palmen. Grosse Sonate f.d. Pianof. für Beethovens Denkmal (Ruins. Trophies. Palms. Large Sonata for the Pianoforte for the Beethoven Monument). That plan, however, went unrealized. At other prepublication moments he envisioned entirely different names for the piece: Phantasien, Fata Morgana, and the tripartite title Dichtungen: Ruinen, Siegesbogen, Sternbild (Poems: Ruins, Victory Arch, Constellation). At the last minute he had the title-page engraving changed to just Fantasie, a term that allowed him more structural liberty than might have been expected of, say, a sonata.

We find Schumann’s imaginary alter-egos, heroic Florestan and languorous Eusebius, inhabiting these pages. The two alternate in the opening movement, with Florestan offering the principal thematic material and Eusebius exhaling dreamy interpolations, including a segment marked Im Legendenton (With the Sound of a Myth). The movement’s coda includes an adagio allusion to Beethoven’s song cycle An die ferne Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), specifically to the setting of the words “Nimm die hin denn, diese Lieder” (Take them then, these songs) in the sixth song of that cycle. This Beethoven citation is sometimes cited as relating to the cryptic lines from a poem by Friedrich Schlegel that Schumann affixed at the head of the Fantasy score: Durch alle Töne tönet / Im bunten Erdentraum / Ein leiser Ton gezogen / Für den, der Heimlich lauscht (Through all the sounds in earth’s motley dream, one soft note can be heard by him who listens stealthily).

The second movement is mostly Florestan music. The technical challenges of Schumann’s Fantasy are many, but nowhere do they exceed the coda of this second movement, where the hands leap distantly in opposite directions over and over, needing to land precisely on notes that cannot both be within the performer’s breadth of sight. The pianist surges ahead with as little fear as possible and hopes for the best: an entirely Florestan attitude. The finale is mostly a tender utterance from Eusebius (with some chromatic transpositions of its sequences being inspired by Franz Liszt, the work’s dedicatee) that leads this monument of the piano’s literature to a glowing conclusion.

—J.M.K.

About the Artist

Emanuel Ax

Born to Polish parents in what is today Lviv, Ukraine, Emanuel Ax moved to Winnipeg, Canada, with his family when he was a young boy. Ax made his New York debut in the Young Concert Artists Series, and in 1974 won the first Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Tel Aviv. In 1975 he won the Michaels Award of Young Concert Artists, followed four years later by the Avery Fisher Prize. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 1979, and will return to the Great Performers Series next month with Itzhak Perlman & Friends (November 10).

His 2024–25 season began with a continuation of the Beethoven for Three touring and recording project with Leonidas Kavakos and Yo-Yo Ma, which took them to European festivals including the BBC Proms. He recently appeared during the New York Philharmonic’s opening week, and will return to the Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, National Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Nashville Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, and Rochester Philharmonic.

Ax has been an exclusive Sony Classical recording artist since 1987. Following the success of his recording of the Brahms trios with Kavakos and Ma, the trio launched an ambitious multi-year project to record all the Beethoven trios and symphonies arranged for trio, of which the first three discs have recently been released. He has received Grammy Awards for the second and third volumes of his cycle of Haydn’s piano sonatas. He also made a series of Grammy-winning recordings with Ma of the Beethoven and Brahms cello sonatas. In 2005, Ax contributed to an International Emmy Award–winning BBC documentary commemorating the Holocaust that aired on the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. In 2013, Ax’s recording Variations received an Echo Klassik Award for Solo Recording of the Year.

Ax is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary doctorates of music from Skidmore College, New England Conservatory, Yale University, and Columbia University.