In This Program

The Concert

Friday February 21, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, February 22, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, February 23, 2025, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Xavier Muzik

Strange Beasts (2024)

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Commissioned as part of the Emerging Black Composers Project

Sergei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Opus 16 (1913/23)

Andantino

Scherzo: Vivace

Intermezzo: Allegro moderato

Finale: Allegro tempestoso

Daniil Trifonov

Intermission

Igor Stravinsky

Le Sacre du printemps (1912)

Part I: The Adoration of the Earth

Introduction—

Harbingers of Spring—

Dances of the Adolescent Girls—

Mock Abduction—

Spring Rounds—

Contest of the Rival Tribes—

Procession of the Sage—

Adoration of the Earth—

The Dancing Earth

Part II: The Great Sacrifice

Introduction—

The Maiden’s Secret Rites and Walking-in-Rounds—

Glorification of the Chosen One—

Summoning of the Ancestors—

Ritual Action of the Ancestors—

Great Sacred Dance of the Chosen One

Lead support for this concert series is provided by The Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Guest Artists.

These concerts, a part of The Barbro and Bernard Osher Masterworks Series, are made possible by a generous gift from Barbro and Bernard Osher.

The Emerging Black Composers Project is underwritten by Michèle and Laurence Corash.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Daniil Trifonov joins the orchestra for Sergei Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2, which was lost in the Russian Revolution, but Prokofiev reconstructed it by memory in 1923. The premiere reportedly “left listeners frozen with fright, hair standing on end.”

A riot broke at the 1913 premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), and more than a century later, the ballet remains a thrilling provocation. Salonen says: “I’ll never stop trying to find the menace and glorious primitivism in this score.”

Strange Beasts

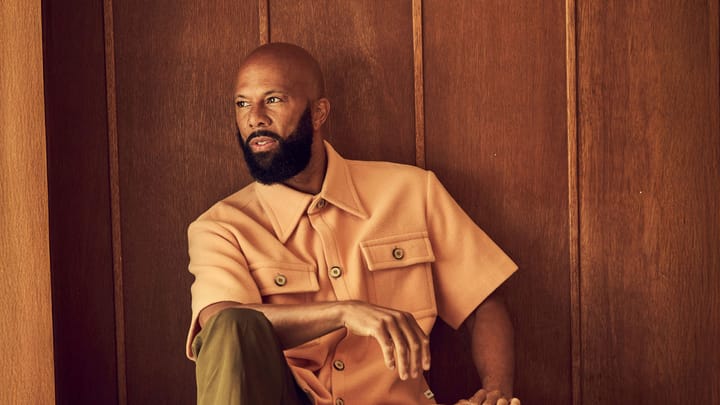

Xavier Muzik

Born: March 5, 1995, in Albuquerque, New Mexico

Work Composed: 2024

SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo (doubling alto flute), 3 oboes (3rd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano (doubling celesta), and strings.

Duration: About 17 minutes

Xavier Muzik is the 2023 winner of the Michael Morgan Prize from the Emerging Black Composers Project, a joint initiative of the San Francisco Symphony and San Francisco Conservatory of music. Raised in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Muzik earned a bachelor’s degree from CalArts and a master’s degree from the Mannes School of Music, where he studied with Jessie Montgomery and Timo Andres. Now based in Los Angeles, Muzik has been commissioned by the Tucson Symphony, ETHEL, New Millenium Brass Ensemble, and the Formalist Quartet. He describes his music as “intentionally organized, narrative in structure, and harmonically rich,” often investigating American views and assumptions about Black and multiracial people. (Learn more about Xavier Muzik.)

In Strange Beasts, Muzik confronts his experience with anxiety and catastrophic thinking, which increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and were only ameliorated by his hobby of street photography around LA. The title alludes to kaiju, the Japanese monster genre, as buildings in his photos often appear as towering forms reminiscent of Godzilla, representative of his own fears.

From the Composer

In his own program note, Muzik writes:

I’d say of all my go-to cognitive distortions, catastrophizing provides me the most—and, truthfully, wickedly desirable—comfort. Small thoughts transmute into haunting poltergeists of my own making: uncanny angels, gluttonous and divine, feeding on my thirst for impossible assurances. These bizarre missionaries come cloaked in protection, promising longevity while selling comforting fictions as if they were the divine gospel, preying on my dread of the unknowable. More often than not, I'm a happy, eager consumer. Why wouldn’t I be? They make me feel safe and seen. To them, I am special. And to them, I am exploitable. In their trickery, they are more beast than angel—their jealousy taking root as they feed me proprietary “what ifs” like candy, delivering fleeting, sugared solaces. They demand my attention, supplanting my agency with unquestioning piety. Their ego makes them dangerous, but it also makes them fragile. They are, and yet, so am I—and in that I reclaim what I give away. . . .

These titular Strange Beasts—manifestations of my catastrophic thinking—are the central antagonists. I’ve cast the buildings I encounter on my photo walks—towering, stoic witnesses to my meandering—as their embodiments, each one hauntingly present and domineering in their insecurity. My music, woven in motive and theme, provides the soundtrack to these encounters, creating a dialogue between my inner and outer worlds, externalizing these beasts and reframing their tyranny as something I can observe, dissect, and ultimately reject.

Photography is a cherished hobby because it offers me an escape from obsession. It situates me in the dynamic, constructive chaos of life, inviting observation and demanding presence—antidotes to the preoccupations that fuel my catastrophic thinking. That’s not to say that as I walk around Los Angeles I am free of these beasts—I still flirt with imagined disasters—but I am no longer merely their sustenance. I can be more. Nevertheless, they haunt me. And as I resist, these monsters grow—comically grandiose and domineering, their fragility and desperation laid bare as they starve as I starve them. Though they may loom large, I persevere. . . .

I invite you to reflect on your strange beasts. How can you starve that which haunts you?

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Opus 16

Sergei Prokofiev

Born: April 23, 1891, in Sontsovka, Ukraine

Died: March 5, 1953, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1912–13 (Reconstructed 1923)

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1953. Erich Leinsdorf conducted with Jorge Bolet as soloist. Most recent—November 2022. Juraj Valčuha conducted with Behzod Abduraimov as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, field drum, snare drum, and tambourine), and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

In its original form, one in which it scandalized more people than it delighted, this concerto is the work of a young man just moving into his 20s. We have no way of knowing how close the surviving version comes to what Prokofiev played at Pavlovsk, the imperial park outside the Russian capital, in September 1913, that original having been lost in a fire during the 1917 Revolution. But the composer wished it understood that in creating the 1924 version he had taken advantage of everything he had learned in a rich and eventful decade: “It was so completely rewritten,” he wrote to friends in Moscow, “it might almost be considered No. 4” (the Concerto No. 3 having appeared in 1921). A few who remembered the early performances suggested that Prokofiev exaggerated, but the matter is past settling. Prokofiev dedicated the score to the memory of Max Schmidthof, a fellow student at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory who committed suicide.

Prokofiev’s biographer Israel Nestiev quotes critics’ expressions of outrage at the premiere: “a Babel of insane sounds heaped upon one another without rhyme or reason” (Yuri Kurdiumov in Peterburgsky Listok) and “a cacophony of sounds that has nothing in common with civilized music. . . . One might think [the cadenzas] were created by capriciously emptying an inkwell on the page” (N. Bernstein in Peterburgskaya Gazeta). The concerto did not much please its Paris audience in 1924 either, when the reconstructed version was premiered by Serge Koussevitzky.

The Music

Prokofiev begins gently with two measures of orchestral stage-setting, leading to two more measures of piano vamp until the appearance of the first theme, a melody of surprising extensions. A contrasting theme introduces an element of caprice and a new repertory of colors. Most of the development and even much of the recapitulation take the form of a huge cadenza, maybe the hugest in any concerto. The orchestral continuation is likewise larger than life, but then a modest restatement of the opening melody brings the movement to a quiet close.

The scherzo is a tour de force of perpetual motion, of nonstop 16th notes for the soloist. “Intermezzo,” at least in the piano repertory, tends to suggest a rather contained sort of music, but this one is fierce. The pianist Sviatoslav Richter said that to him it evoked “a dragon devouring its young.” Prokofiev’s inventiveness in piano figuration is remarkable.

In a sense, the second and third movements are both intermezzi, music on a far smaller scale than the first movement and the finale. The last movement reverts to the expansive manner of the first and also has a cadenza as its focal point. The entry into this cadenza is one of Prokofiev’s wittiest strokes in the work. This movement brings together the Scythian wildness of the Intermezzo and the touching, narrative lyricism of the first movement’s Andantino. That the harmonic boldness of the last pages left some of the vacationers at Pavlovsk with their hair standing on end, one need not doubt.

—Michael Steinberg

Le Sacre du printemps

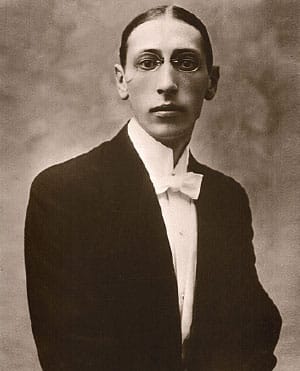

Igor Stravinsky

Born: June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, Russia

Died: April 6, 1971, in New York

Work Composed: 1911–12 (rev. 1947)

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1939. Pierre Monteux conducted. Most recent—March 2022. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, piccolo (3rd flute doubling 2nd piccolo), alto flute, 4 oboes, English horn (4th oboe doubling 2nd English horn), 3 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet (2nd clarinet doubling 2nd bass clarinet), 4 bassoons, contrabassoon (4th bassoon doubling 2nd contrabassoon), 8 horns (7th and 8th doubling tenor tubas), 4 trumpets, high trumpet in D, bass trumpet, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, timpani (2 players), percussion (bass drum, tam-tam, triangle, tambourine, guiro, and antique cymbals), and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

Thanks to the success of The Firebird, among other works, Igor Stravinsky was somewhat famous before May 29, 1913, but the events of that date—the premiere of Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) and the accompanying riot by the Paris audience—catapulted him, and modern music, onto a path from which there was no turning back. The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées had opened less than two months before on Avenue Montaigne, a street known for its upper-crust, essentially conservative establishments. The theater’s initial bout of programming was far from scurrilous, and when the spring season concluded with the “saison russe” of opera and ballet, the audience was ready to let loose. A press release reprinted in several Paris newspapers on the day of the premiere tantalized through references to the “stammerings of a semi-savage humanity” and “frenetic human clusters wrenched incessantly by the most astonishing polyrhythm ever to come from the mind of a musician,” promising “a new thrill which will surely raise passionate discussions, but which will leave all true artists with an unforgettable impression.”

The audience came ready to participate in accordance with their aesthetic stances; some even had the foresight to arm themselves with whistles. Audible protests apparently accompanied the performance from the opening bars, but things stayed somewhat under control until halfway into the introduction—which is to say, for about the first minute of the score. Then, to quote Stravinsky, they escalated into “demonstrations, at first isolated, [which] soon became general, provoking counter-demonstrations and very quickly developing into a terrific uproar.” These continued throughout the performance, during which partisans brawled, socialites slapped their neighbors, gentlemen challenged each other to duels, the house lights flashed on and off, and Vaslav Nijinsky stood on a chair just offstage to shout cues to the perplexed dancers. Thus was history made.

The Music

The ballet’s scenario, set in pagan Russia, was created jointly by Stravinsky and the designer Nicholas Roerich. Stravinsky described:

FIRST PART: THE ADORATION OF THE EARTH

The Spring celebration. The pipers pipe and young men tell fortunes. The old woman enters. She knows the mystery of nature and how to predict the future. Young girls with painted faces come in from the river in single file. They dance the Spring dances. Games start. The Spring Korovod [a stately dance]. The people divide into two opposed groups. The holy procession of the wise old men. The oldest and wisest interrupts the Spring games, which come to a stop. The people pause trembling before the Great Action. The old men bless the earth. The Kiss of the Earth. The people dance passionately on the earth, sanctifying it and becoming one with it.

SECOND PART: THE GREAT SACRIFICE

At night the virgins hold mysterious games, walking in circles. One of the virgins is consecrated as the victim and is twice pointed to by fate, being caught twice in the perpetual circle of walking-in-rounds. The virgins honor her, the Chosen One, with a marital dance. They invoke the ancestors and entrust the Chosen One to the old wise men. She sacrifices herself in the presence of the old men in the Great Sacred Dance, THE GREAT SACRIFICE.

Musicologists have shown that a fair amount of the melodic material in Le Sacre du printemps has at least some connection to actual folk melodies—including the famous, high-pitched bassoon solo that opens the piece, which traces its roots to a Lithuanian folk tune. The primal, folk-like spirit of the melodies is translated into a bold musical context marked by polytonal harmonies, unorthodox metric alternations, and rhythmic displacements; this constant tension between the simplistic and the complex is a hallmark of the piece. The overriding character of the score resides in proximity to violence.

Like the audience, critics were divided about Le Sacre du printemps, but some simply foundered in a state of perplexity. Henri Quittard’s assessment appeared in Le Figaro two days after the premiere:

Here is a strange spectacle, of a laborious and puerile barbarity . . . we are sorry to see an artist such as M. Stravinsky involve himself in this disconcerting adventure . . . Certainly the history of music is full of anecdotes where the ignorance of critics shines forth when they were unable to recognize creative genius when it appeared. Is the future saving up a triumphant revenge for new music as M. Stravinsky seems to understand it today? That is its own secret. But, to tell the truth, I doubt that our disgrace is very near.

Quittard was wise to hedge his bets. After a cooling-off period—and a world war—Diaghilev produced Le Sacre du printemps again with new choreography. That version provoked far less demonstrative passion than the premiere had seven-and-a-half years earlier, and since that time quite a few other productions have made their way to the stage. Nonetheless, Le Sacre du printemps would never acquire the popularity as a staged ballet that it would as a concert work. Within a year of its ballet premiere it was offered in concert both in Moscow and in Paris, and it would quickly earn the preeminent place in the symphonic literature that it retains to this day.

—James M. Keller

A portion of this note previously appeared in the program book of the New York Philharmonic and is used with permission.

About the Artists

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

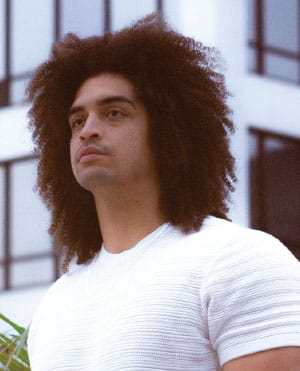

Daniil Trifonov

Daniil Trifonov is a solo artist, champion of the concerto repertoire, chamber and vocal collaborator, and composer. He won a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Solo Album in 2018 with Transcendental, the Liszt collection that marked his third title as a Deutsche Grammophon artist. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in January 2014 as a Shenson Young Artist.

This season, Trifonov undertakes season-long artistic residencies with both the Chicago Symphony and Czech Philharmonic. He also opened the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra’s season and tours Europe with the Bamberg Symphony and Montreal Symphony. His latest album, My American Story on Deutsche Grammophon, pairs solo pieces with concertos by George Gershwin and Mason Bates.

Trifonov’s Deutsche Grammophon discography includes the Grammy-nominated live recording of his Carnegie Hall recital debut; Chopin Evocations; Silver Age, for which he received Opus Klassik’s Instrumentalist of the Year/Piano Award; the Grammy-nominated double album Bach: The Art of Life; and three volumes of Rachmaninoff works with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, of which two received Grammy nominations and the third won BBC Music’s 2019 Concerto Recording of the Year. Named Gramophone’s 2016 Artist of the Year and Musical America’s 2019 Artist of the Year, Trifonov was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 2021.

During the 2010–11 season, Trifonov won medals at three of the music world’s most prestigious competitions: third prize in Warsaw’s Chopin Competition, first prize in Tel Aviv’s Rubinstein Competition, and both first prize and grand prix in Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Competition.