In This Program

- Welcome

- A Visionary at the Keyboard

- Music With Friends

- Community Connections

- Meet the Musicians

- Print Edition

Welcome

At the San Francisco Symphony, our audiences are at the heart of everything we do. Whether you’re discovering live orchestral music for the first time or returning season after season, your curiosity, enthusiasm, and support drive the creativity and innovation that define our programming.

When we inaugurated our SoundBox series more than a decade ago, our goal was to create a space where adventurous music lovers could experience the artistry of our San Francisco Symphony musicians in an entirely new way. SoundBox has been an exciting experimental lab for creativity, as we’ve invited collaborators from a wide array of disciplines to exchange ideas and explore new possibilities. Our SoundBox performances are elevated by the curiosity of our audiences, who arrive with open minds and a hunger for what’s next. This month, composer and pianist Courtney Bryan—whose work threads together elements of jazz, classical, and sacred music in pieces that illuminate African American experiences—curates an inspiring and wide-ranging program.

Just as SoundBox has encouraged bold creativity and fresh experiences, our free Community Ticket Program is building connections with audiences across the Bay Area. Launched in 2021, this initiative has already provided more than 37,000 tickets to local nonprofits and the constituents they serve. It’s a joy to introduce live orchestral music to new audiences and foster a love for the San Francisco Symphony.

The enthusiasm and excitement our audiences bring—whether at SoundBox, through our free Community Ticket Program, or at any of our concerts—inspire us every day. This energy fuels our creativity and strengthens our connection to San Francisco and the Bay Area. We hope you’ll carry the experience with you and share it with others, extending the reach and impact of the San Francisco Symphony.

Matthew Spivey

Chief Executive Officer, San Francisco Symphony

A Visionary at the Keyboard

Víkingur Ólafsson brings warmth to Davies Symphony Hall(with a little help from his friends) • By Steve Holt

On his recent album From Afar, Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson was so intent on capturing some of his childhood musical memories, he recorded the tracks on an upright piano.

“When I was growing up, I actually had an upright piano in my bedroom,” he says. “Since the album features smaller pieces that represent my musical upbringing and my musical roots in Iceland, and there was an upright in the studio, I decided to give the upright a really serious treatment. And then I liked it so much I released the album on both upright and grand.”

This glimpse into Ólafsson’s imagination and creativity reflects his willingness to push the envelope in service of his art. Those traits will take center stage when he performs at the San Francisco Symphony twice in the coming months.

The January concerts feature John Adams’s After the Fall, a San Francisco Symphony commission and world premiere, written especially for Ólafsson. “I’ve known John now since our first concerts together, with his Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? [coincidentally premiered by Yuja Wang, Ólafsson’s recital partner here in March]. John and I played the very last two weeks before the music world shut down because of COVID. From that point on, we became very good friends and very much partners in crime in music.”

Ólafsson says Johann Sebastian Bach is a major presence in After the Fall. “You could say that about so many masterworks: Brahms’s First Piano Concerto, almost every piece that Beethoven wrote. Bach is perhaps the most important composer for me, the one composer who I play basically daily, one way or another. When John was writing this concerto, he had listened to quite a lot of me playing Bach. I’ll just say that in After the Fall, it’s a very decisive turn of events that leads to J.S. Bach’s visit to this music.”

For Ólafsson, having a concerto written especially for him is like going to a master tailor. “What John has written for me feels musically very bespoke, in terms of the overall sonority, and a sense of fantasy and structure and colors; the musical narrative as a whole. It seems almost familiar to me, before I have even given the world premiere. The tailor has done a masterful job!”

As part of his preparations, Ólafsson will travel to San Francisco a week before the premiere for sessions with Adams. “It’ll just be me and John, and hopefully a rehearsal pianist, to play the orchestra part. It’ll be a very intense week of shaping it up for interpretation and for the premiere. It’s always exciting to go into the process and face that huge question mark that a world premiere always has.”

After the Fall also marks Ólafsson’s first time working with conductor David Robertson. “It’s very unusual for me to perform a world premiere with a conductor I’ve never worked with before. But he’s a tremendous conductor, and a great authority on John’s music. I just know this piece is unbelievably beautiful and strikingly dramatic. If that doesn’t come across to the public, it’s probably my fault!”

Ólafsson is equally looking forward to his return to Davies Symphony Hall in March for his duo recital with Yuja Wang. What made them team up? “Pianists like us don’t often meet, because we’re rarely in the same place at the same time,” he says. “But somehow, Yuja and I were playing the same festival in Latvia in 2021. It turned out we were quite fond of each other’s work, and she suggested that we try a piano duo, which I don’t think either of us had done before, and I thought, why not? We came up with a highly unusual program, a wonder program I’d call it, and we’ve done it about ten times in Europe.”

“The idea with this and so many of my recital programs is to hopefully blur the boundaries a little bit of what is new and what is old,” he says. The program opens with Luciano Berio’s 1960s work Wasserklavier, which leads into the F-minor Fantasy of Schubert. “For a brief period it feels like they’re contemporaries, as opposed to people separated by over a hundred years,” Ólafsson notes. Also on the program are three works by American composers—Adams’s Hallelujah Junction, Conlon Nancarrow’s Study No. 6, arranged by Thomas Adès, and John Cage’s Experiences No. 1—and Arvo Pärt’s Hymn to a Great City and a two-piano version of Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphonic Dances, Opus 45. “It’s sort of off-the-beaten-path repertoire that I think works very beautifully,” Ólafsson says.

Both Ólafsson and Wang play to rapturous audiences all over the world. But what are the dynamics when two piano titans share a stage? “Two grand pianos can feel overwhelming, but they can also feel incredibly fascinating, if you know how to treat this kind of dual machine, if you know how to texturize it.” He finds the nature of this collaboration to be especially stimulating. “With Yuja and with this program, I think our soloist egos withdraw a little bit, even if we are certainly challenging each other. But it has to be about the music and how you can make two pianos and 176 keys into something magical. In the end, you meet in that place that is the music. When we perform together it doesn’t feel like ‘show business,’ like two pianists competing for attention on stage, but rather two pianists creating something together that is larger than the two individuals.”

Music With Friends

Guest conductor James Gaffigan returns to the San Francisco Symphony

James Gaffigan joins the San Francisco Symphony this month to conduct a program featuring Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto with Ray Chen, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony. Gaffigan was associate conductor of the San Francisco Symphony from 2006 to 2009 and is now general music director of Berlin Comic Opera and music director of the Queen Sofía Palace of the Arts in Valencia, Spain.

What’s it like to return to the San Francisco Symphony, an orchestra you have a long history with?

I’m looking forward to returning to the San Francisco Symphony for many reasons, both personal and musical. Personally, I know many members of the orchestra. I’ve known some of them since a young age when we were beginning our careers together, and we’re still friends. I have only incredible memories of being there as the associate conductor in the early 2000s, when I was doing a lot of repertoire for the first time with such a great orchestra. We’ve had lots of culinary and cultural adventures around the city too.

What are some of the fundamental qualities that define the SF Symphony?

In returning over time, I’ve loved to see the development of the orchestra, the new hires, and all of the new members that I’ve yet to meet. If I had to define the San Francisco Symphony with one word, it’s “versatility.” They’re one of the greatest orchestras in the country, and they can literally do anything—any style—and switch between different styles within one program. I really look forward to returning and making music with them.

What are your must-sees when you’re back in San Francisco?

I look forward to visiting many places in the city that hold many beautiful memories. There’s the Ferry Building, and the market there—and many, many coffee places. I remember when Blue Bottle Coffee first opened, and I went literally every morning before rehearsal at the San Francisco Symphony.

And I especially love exploring outside the city. Right across the Golden Gate Bridge there’s Muir Woods, one of my favorite places on earth. Drive a little further and you’re in wine country, in Sonoma, Healdsburg, and Napa. I have extraordinary memories of being there, and so many places in and around San Francisco that are dear to my heart.

Tell us a little about the program you’ll be conducting in San Francisco. How do the works fit together?

This program has a combination of very different genres. I always think it’s important that American orchestras celebrate the great American composers alongside the great living American composers. Of course, Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto is a masterpiece, and one of the most famous American masterpieces performed regularly. And what better way to showcase it than with the San Francisco Symphony and Ray Chen.

We have a living composer, Missy Mazzoli, one of the best-known American composers working today, and rightfully so. She has her own voice, her own style, and with the San Francisco Symphony being as versatile as they are, they are truly able to do it justice.

The second half of the program showcases my love for Prokofiev as a composer, and the orchestra’s virtuosity in performing his work. Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 is his grandest symphony, and a work that I remember hearing Michael Tilson Thomas conduct with the Orchestra when I was associate conductor. It has everything in it—like a mini opera in symphony form, with so many emotions wound up into one piece. I think it will show the musicians of the San Francisco Symphony in an incredible light, so I look forward to bringing my love and passion for this piece into the performance by this particular orchestra.

You work in both the symphonic and operatic worlds. How does your approach differ when conducting an opera versus a symphonic concert, and what do you find most rewarding about each?

The truth is, I enjoy conducting opera and symphonic repertoire equally. They’re completely two different genres that call for very different skillsets and talent. Operatically, I love how many pieces have to come together to complete the puzzle and how many people are involved in the production. I love working with singers—working with their unique voices, supporting them and basically making their lives easier: They have enough to think about with what they need to do and sing onstage, so it’s my job to be as flexible as possible and make them as comfortable as they can be. I believe that there’s a lot of compromise that one must be able to make as a conductor of opera. So it’s not for everyone: If you’re a control freak, you shouldn’t be conducting opera!

Symphonic repertoire is extraordinary because it showcases the orchestra itself. There’s nothing to distract you from the symphonic experience, allowing you to just revel in the sound of the orchestra. I like to pay very close attention to the textures of orchestra repertoire while appreciating the rich experience of the music that a listener will experience as a member of the audience: They’re going to “shut off” for a while, and just revel in the sounds of the symphonic orchestra.

I find that most orchestras around the world are continuing to develop toward an even higher and more versatile level, and I love exploring repertoire that’s not often played in the regular subscription series. I enjoy combining the lesser-known works of a great composer with the works that are more familiar.

But I love both genres, and I need them both in my life.

What are some of your biggest hopes for the future of classical music in America?

My hope is that it can be an outlet for all young people at a young age. I was lucky in the public school system of New York City to have access to what we call classical music. It was an incredible outlet for me as a young boy: for emotions, for passions. I found great pleasure in working on my music alone or working on my music with colleagues—whether it was rock music or jazz or classical.

I think this should be available for every child in America and unfortunately, it’s not. It’s a dream of mine that within the normal education system, music can become a priority as high as mathematics or reading or history, because it exercises a very special part of the brain that has a lot to do with empathy and getting along well with others and listening well to others.

I think we have a big problem in America of not listening to one another, which is the cause of many conflicts and misunderstandings. I think the idea of getting together and playing music, or even singing a simple song, is a way of bonding beyond words. That’s my biggest wish for America.

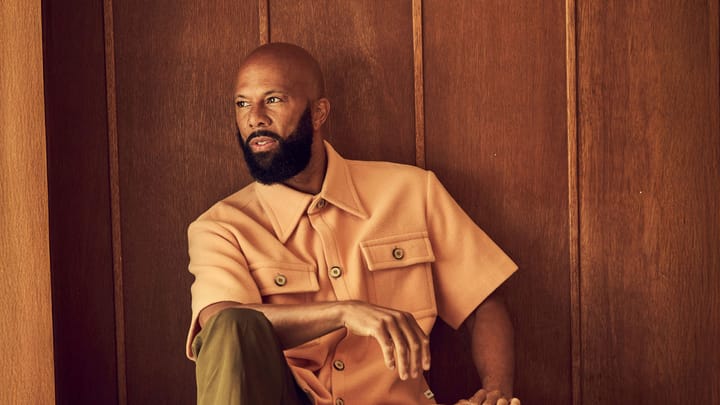

Community Connections

Creativity Explored

Creativity Explored is a studio and gallery in San Francisco that supports a neurodiverse community of over 140 artists with disabilities, providing opportunities to create, exhibit, and sell their work. Founded in 1983, Creativity Explored has facilitated the careers of hundreds of neurodiverse artists and serves as a model in the field of art and disability worldwide. Acquisitions in the last year by the SF Museum of Modern Art and Oakland Museum of California have affirmed the place of Creativity Explored artists, and all artists with disabilities, in the contemporary art world. The organization’s life-changing programs continue to open doors of inclusion and to center the personhood and creative vision of people with developmental disabilities. Creativity Explored is a source of community, empowerment, and dignity.

Visit Creativity Explored’s magical studio and gallery, full of thousands of works for sale, Thursday–Saturday. For more information, visit creativityexplored.org.

The San Francisco Symphony thrives on collaboration, and we’re proud to work with the most creative, innovative groups and individuals shaping the Bay Area today.

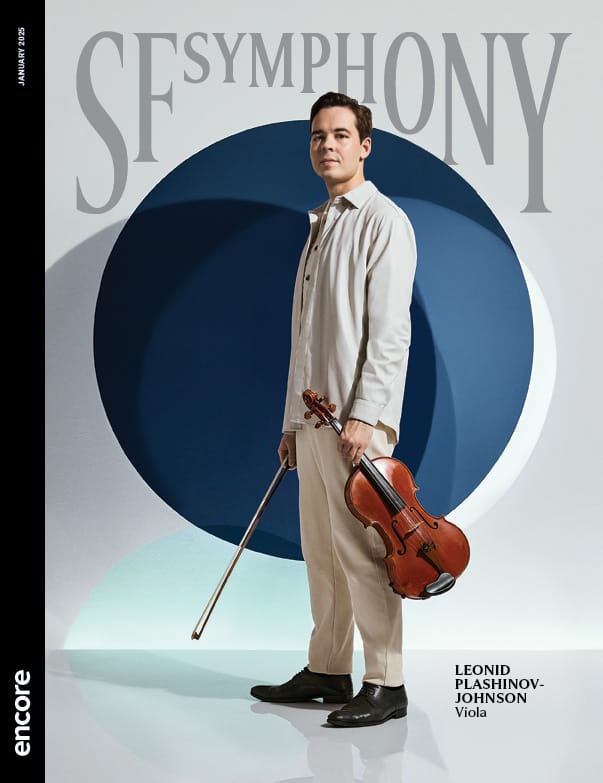

Meet the Musicians

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson • Viola

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section at the beginning of the 2022–23 season.

What are your memories of being a child in Siberia?

I was born in a city called Tyumen. It’s two time zones east of Moscow and north of Kazakhstan. It’s a pretty big city now. I remember the winters were obviously very cold—we got down to the minus 30s, however the summers sometimes reached triple digits. There’s also a different dimensional scale of space, nature, and wilderness that I haven’t seen elsewhere. My mother and I left for the UK when I was six, but my father’s whole side of the family is still there so I used to enjoy visiting.

What was your path from there?

In the UK, I spent the ages of 10–18 at the Yehudi Menuhin School. It’s a very small school of around 70 string and piano students, ages 8–18, of all nationalities. It was transformative to me as a young musician, and as a boarding school, it also taught me to live away from home from a young age. I studied the violin there with Lutsia Ibragimova, who was also Russian and had even lived in Yekaterinburg, near to my hometown. After switching to viola, I learned from Andriy Viytovych, who was at the time the principal viola of the Royal Opera House. I moved to the US in 2015 to study at the New England Conservatory under Kim Kashkashian. These three teachers had a tremendous impact on me.

How did you begin playing viola?

When I was at the Menuhin School around 13 or 14 years old, there were no dedicated viola players, so I was one of the students they picked to do double duty on viola in chamber music or string orchestra settings, maybe because I have larger hands. Over time, I enjoyed my life with the viola a bit more.

Did something in particular convince you to switch to viola?

I was about 17 when I made the switch. I was put in a really good chamber group playing the Schubert C-major Cello Quintet, and they gave me a really beautiful instrument, Menuhin’s own Testore viola, to play for the year. And I had such a great time playing that piece, on that instrument, with those people. By the end of the year, I had gotten enough feedback about my life as a violist, as well as my own experience of it, to switch full-time.

What were your next steps out of school?

I played in the St. Louis Symphony before coming to San Francisco. I still spend a lot of time trying to understand how to play my instrument better and perhaps more in an exploratory way than before. When you transition out of school to not having a teacher, there’s this unfamiliar responsibility that your future is in your own hands. You have to think about what you want that to look like, and actively shape the kind of musician you want to be.

Do you remember your first concert with the SF Symphony?

It was Star Wars: A New Hope with live orchestra, and it was such a fun concert to play. I’m a big Star Wars fan and especially love those glorious scores by John Williams, so to do that as one of the first things was really special.

What do you find special about a live orchestra?

It’s so rare these days to hear music or sound that is not coming out of a speaker and not processed through something. It’s kind of wild that on stage we have 100 people playing instruments that were handcrafted as a result of hundreds of years of development, and we are literally creating those sound waves that are hitting your ears. So you feel more connected to every sound and note—and on a bigger scale, every movement, gesture and intention—experiencing it as the real living thing rather than a representation. I think all music can be incredibly expressive, whether it’s jazz or metal (and I love both). But that is going through a speaker system, and though you’re getting the result of something happening in front of you, it’s not the same thing that happens from purely acoustic instruments.

What are your hobbies outside of music?

I have always loved cars, so I cherish every drive I get in my red Mazda Miata! I managed to complete a bucket-list item recently when I went to France to watch the 24 Hours of Le Mans Race. It was quite the experience, and I was wearing ear protection, so I’m okay! I enjoy good books as well. I’ve recently been reading Daemon Voices by Philip Pullman. I love how he really brings storytelling and music making together in an interesting and refreshing way. We hear all the time from musicians about how music is telling a story, but I don’t often hear a writer talking about stories as if they’re music.

Print Edition