In This Program

- Welcome

- Víkingur Ólafsson: A Visionary at the Keyboard

- Radu Paponiu: Conductor and Teacher

- Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser: Putting It All Together

- Community Connections

- Meet the Musicians

- Print Edition

Welcome

One of my most cherished memories with the San Francisco Symphony is attending Adventures in Music (AIM) concerts with my daughter when she was in school. For more than 35 years, the Fisher Family Adventures in Music program has brought the joy of music education and extraordinary live performances to countless San Francisco Unified School District elementary school students—all free of charge.

AIM concerts are always a breath of fresh air—filled with the energy of students eager to engage with the music. This month, thousands of SFUSD students in grades 1 and 2 will experience this excitement firsthand as they join us at Davies Symphony Hall for a concert crafted just for them.

This month also highlights the breadth of our education programs. Alongside AIM concerts, the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra, which offers tuition free music education to talented young Bay Area instrumentalists, performs its second concert of the season. Additionally, our annual Teen Night concert, now in its fourth year, invites students to experience the Symphony in a new way. As Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser, our Resident Conductor of Engagement and Education, who is on the podium for Teen Night, explains: “Teen Night is a time when the innovation of the San Francisco Symphony shines through. Our next audience comes to Davies Symphony Hall and experiences music in a way they can never have anticipated, in a way that will leave an indelible mark on their memory.” You can read more about Daniel on page 14.

Whether we’re inspiring our youngest listeners or engaging with teenage music lovers, we take pride in nurturing the audiences of tomorrow. Thank you for being a part of this experience today—and for helping us bring the transformative power of music to the young people of our community.

Priscilla B. Geeslin

Chair, San Francisco Symphony

A Visionary at the Keyboard

Víkingur Ólafsson brings warmth to Davies Symphony Hall (with a little help from his friends) • By Steve Holt

On his recent album From Afar, Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson was so intent on capturing some of his childhood musical memories, he recorded the tracks on an upright piano.

“When I was growing up, I actually had an upright piano in my bedroom,” he says. “Since the album features smaller pieces that represent my musical upbringing and my musical roots in Iceland, and there was an upright in the studio, I decided to give the upright a really serious treatment. And then I liked it so much I released the album on both upright and grand.”

This glimpse into Ólafsson’s imagination and creativity reflects his willingness to push the envelope in service of his art. Those traits take center stage in two performances at the San Francisco Symphony this season.

Ólafsson’s January concerts featured John Adams’s After the Fall, a San Francisco Symphony commission and world premiere, written especially for Ólafsson. “I’ve known John now since our first concerts together, with his Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?,” which was written for pianist Yuja Wang. “John and I played the very last two weeks before the music world shut down because of COVID. From that point on, we became very good friends and very much partners-in-crime in music.”

Ólafsson joins Wang, another of his musical partners-in-crime, to perform a wide-ranging duo recital this month. “Pianists like us don’t often meet, because we’re rarely in the same place at the same time,” he says. “But somehow, Yuja and I were playing the same festival in Latvia in 2021. It turned out we were quite fond of each other’s work, and she suggested that we try a piano duo, which I don’t think either of us had done before, and I thought, why not? We came up with a highly unusual program, a wonder program I’d call it, and we’ve done it about 10 times in Europe.”

“The idea with this and so many of my recital programs is to hopefully blur the boundaries a little bit of what is new and what is old,” he says. The program opens with Luciano Berio’s 1960s work Wasserklavier, which leads into the F-minor Fantasy of Schubert. “For a brief period it feels like they’re contemporaries, as opposed to people separated by over a hundred years,” Ólafsson notes. Also on the program are three works by American composers—Adams’s Hallelujah Junction; Conlon Nancarrow’s Study No. 6, arranged by Thomas Adès; and John Cage’s Experiences No. 1—as well as Arvo Pärt’s Hymn to a Great City and a two-piano version of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances. “It’s sort of off-the-beaten-path repertoire that I think works very beautifully,” Ólafsson says.

Both Ólafsson and Wang play to rapturous audiences all over the world. But what are the dynamics when two piano titans share a stage? “Two grand pianos can feel overwhelming, but they can also feel incredibly fascinating, if you know how to treat this kind of dual machine, if you know how to texturize it.” He finds the nature of this collaboration to be especially stimulating. “With Yuja and with this program, I think our soloist egos withdraw a little bit, even if we are certainly challenging each other. But it has to be about the music and how you can make two pianos and 176 keys into something magical. In the end, you meet in that place that is the music. When we perform together it doesn’t feel like ‘show business,’ like two pianists competing for attention on stage, but rather two pianists creating something together that is larger than the two individuals.”

Conductor and Teacher

Radu Paponiu joins the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra • By Benjamin Pesetsky

ON A SATURDAY AFTERNOON in early October, the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra convened for their third rehearsal of the season. Radu Paponiu, the YO’s newly appointed Wattis Foundation Music Director, took the Davies Symphony Hall stage with Harry Jo, a high-school violinist who won the 2023–24 Concerto Competition on his second instrument, alto saxophone. At the downbeat, they ripped into Takashi Yoshimatsu’s Cyber Bird Concerto, a jazz-influenced Japanese work from 1994. The saxophone, brilliant and a bit cheeky, wove over a rapid drumbeat laid down by the percussion section. The strings joined in a swell, responding to the soloist’s lines, and sharp piano chords urged it all along. After an impressive read-through, Paponiu flipped back to work on the very first note.

“No hesitation! All together!” he tells the double basses, who ground the first bar with a low pizzicato C. What first sounded like a racket of notes comes together as a collective snap on the second try. Then Paponiu turns to a cacophonous, free-jazz section that asks members of the orchestra to improvise. He works through it until the crescendo takes the right climactic shape.

After a break, the YO turns to an older, more familiar piece—Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4. “D natural! Nothing else!” Paponiu reminds the players as they tune a chord. Then he talks briefly about the piece’s history and how it should be felt. “We know from Tchaikovsky’s letter that this is about anxiety,” Paponiu says. “This is tense.” In 1878 Tchaikovsky wrote a letter to his patron describing the Symphony’s theme as “the sword of Damocles over our heads.” The young musicians play the opening again, more focused this time on the composer’s emotional intent.

For the last half hour of this special rehearsal, parents are invited into the hall to hear a preview of what the orchestra has been working on. Though more than a month of rehearsals remain before the first concert, the YO already gives a polished take on Tchaikovsky’s finale and Bernstein’s Overture to Candide. Parents watching closely might have noticed Jacob Nissly, the SF Symphony’s Principal Percussion, hovering in the back, advising a triangle player. Several other Symphony musicians who serve as coaches for the YO could be spotted on stage and in the audience—a superabundance of expert mentors that music students hardly get anywhere else.

Founded in 1981, the SFSYO offers tuition-free training to more than 100 young musicians (ages 12–21) from across the Bay Area; its ranks are filled each year through competitive auditions. Many go on to professional careers—five members of the SF Symphony are even alumni. The SFSYO’s first Music Director was Jahja Ling, followed by David Milnes, Leif Bjaland, Alasdair Neale, Edwin Outwater, Benjamin Shwartz, Donato Cabrera, Christian Reif, Daniel Stewart, and now Radu Paponiu, who has been appointed to a three-year term.

Paponiu hails from Romania, where he began playing violin at age seven. He first came to the United States in 2007 to join the Perlman Music Program near Long Island, and later studied violin at the Colburn School in Los Angeles and conducting at New England Conservatory in Boston. Most recently, he served as associate conductor of the Naples Philharmonic in Florida and music director of the Naples Philharmonic Youth Orchestra. He has also been music director of the Southwest Florida Symphony, a member of the conducting faculty at the Juilliard Pre-College, and has guest conducted in Europe and America. His wife, Blair Francis Paponiu, is the SF Symphony’s Associate Principal Flute, holding the Catherine & Russell Clark Chair. They met in Naples, where she played before joining the SF Symphony in 2023.

Backstage at the end of rehearsal, Paponiu sat down for an interview.

What are your first impressions of the SFSYO?

Already I feel that when you have this kind of talent, there really is no ceiling to what we can achieve. Each week I can’t wait for the next rehearsal to see how much further we will get.

Did you grow up playing in youth orchestras yourself?

I’m from a small town in Romania, but we had an art school with both painting and music. When I was nine, I joined the string orchestra there. I still remember being so excited, going to the first rehearsal, playing the first bar, and then being lost the rest of the time! But it was a huge inspiration because I loved the idea of not just practicing by myself, but going and playing with others. At 12 I moved to Bucharest to attend the George Enescu Music High School, and I played in the Central European Initiative Youth Orchestra each summer. Students from across the region would get together, rehearse for two weeks, and then tour Europe. While I was in college, I played in the American Youth Symphony in LA and was also an assistant conductor there. As it turns out, I’ve always been involved in a youth orchestra program, whether playing, coaching, or conducting.

What drew you to conducting?

I always loved the idea of studying the score and perhaps discovering something new. To this day, I find it so exciting to deal with some of the greatest works of art that humanity has created. Every time you open a score, there’s something to see. And then whatever you learn, you can go and share with others.

How exactly does a conductor study a score?

Every conductor has a different way, and it changes with time, because once you become familiar with a piece, it’s very different when you return to it. I was fortunate to play a lot of pieces on the violin before conducting them. But I do have a process of phrase analysis where I try to get into the composer’s mind and understand how the piece is built. I think harmony is ultimately what gives the form. Then I ask, what did the composer really want to say? And what do I want to say?

Do you encourage students look at the full score? How should they approach it?

This is where the fun begins! It’s not just learning your own part, but seeing how it fits with everyone else. Any sort of studying, you cannot go wrong. That’s how I learned—just being every day in the score, asking questions. First, find your instrument and try to follow along. Then ask, is anyone playing the same line with me? You’ll get a glimpse into what the composer was thinking.

As a string player, how did you learn to work with students who play other kinds of instruments?

Ever since I started, I’ve tried to say yes to every single thing I was asked to conduct. So I’ve gotten to work with woodwinds, contemporary groups with lots of percussion, and brass ensembles. It takes a lot of work to get that experience, but it’s the most helpful way to learn about instruments and how to address their particular issues. And of course, the SFSYO has incredible access to the musicians of the San Francisco Symphony, and that makes a huge, huge difference!

How do you choose what pieces to play with the YO?

I like to have a path every year. Program to program, I’m thinking about difficulty and how it can increase a little bit. I also want to work on ensemble technique and listening, so I try to think of music that is really going to force us to do that. I think it’s very important to have a progression throughout the season, and to start with repertoire that can teach a lot.

What are the biggest benefits of playing in a youth orchestra?

I really think it’s one of the most amazing experiences you can have. It teaches you things that apply in everything you do. You need to have the responsibility and discipline to practice the music, and then bring it to rehearsal and create a positive experience for everybody. You really learn to work with others—sometimes you might love a musical idea and be happy to do it, and sometimes maybe you’d prefer to play it a little bit differently. But you have to try it both ways, and many times you’ll change your mind and see it from a new angle.

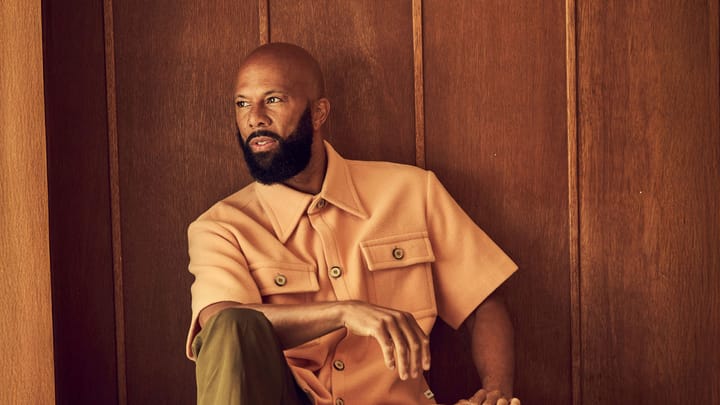

Putting It All Together

Conductor Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser on connecting

with audiences of all ages • By Steve Holt & Steven Ziegler

For the past several seasons, SF Symphony Resident Conductor of Engagement and Education Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser has delighted Bay Area audiences with his easygoing and engaging podium presence. He recently extended his contract with the San Francisco Symphony three years, through the 2026–27 season.

Is an audience full of kids different from a regular concert audience?

[Laughter] If you don’t engage the young people immediately, you feel the energy leave the room very quickly! The thing is, they give you a lot of energy too; you come out on stage to uninhibited applause and yells and that gives you a lot. There’s a real need to explain things in a way that’s fun, exciting, and understandable for all young people, including those who may not have English as their first language.

What do you try to accomplish with a concert for children?

Provide an experience they will remember five to 10 years later. If you have a good amount of music kids are somewhat familiar with, then you can challenge them with things they’re unfamiliar with. Surprise the audience! That variety can help provide a memorable experience.

For example, I’ll engage students by doing experiments with sound in the moment, changing the way that they hear things on stage. I have a demonstration where I teach them how to recognize when the orchestra is sharp or flat. They can hear that. I like to treat the concerts as part concert, part experiment, allowing the students some agency so they’re active and participating in ways that change the sound on stage.

How does this idea of engagement translate into your other work?

One of the most important things I always think about is “First, Last, and Only.” For some people in the audience this is the first time they’re going to hear an orchestra live. And their decision to attend another concert later on is going to be based on what they experience today. For some, it’s their last performance, especially if I go to a hospital or a senior citizens home, or a hospice, or prison. For a lot of these people this is the last time they will be hearing orchestral music live. That’s a very, very special thing. Or, for some people, it’s the only time they will hear a live orchestra. And you just don’t know. So, with education concerts, it really, really raises the stakes. It isn’t just a kids’ concert: it’s a future violinist’s concert, or teacher, or singer, or conductor, or donor, or board member.

Can you share your experience forging a path in a traditionally less diverse field?

It’s interesting, because it never occurred to me that I could not be a professional orchestra conductor. I was often the only Black kid in my class, and all my music teachers were white, but all of them said “absolutely, you should be a conductor.” My family was like, “go for it!” Fortunately, I haven’t encountered overt racism on my path. I like the fact that when people—especially young people—see me, they see a Black conductor. Because now they know hey, maybe if they want to be a conductor, they can be a conductor too. This world is for them. But I long for the day when a Black conductor isn’t a novelty.

You obviously have a great relationship with the San Francisco Symphony.

Never in my wildest dreams as a youth did I think I’d be conducting the San Francisco Symphony. Once you’ve had that experience, you carry that sound with you. You carry the response of the musicians with you and you know that experience makes you so much better for everything else. With a group this good, what you can accomplish as a conductor is only limited by your own imagination.

Steven Ziegler is the San Francisco Symphony’s Editorial Director.

Community Connections

Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Bay Area

Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Bay Area’s mission is to create and support one-to-one mentoring relationships that ignite the power and promise of youth. The organization pairs young people referred to its program by parents, guardians, teachers, and social workers with a screened, qualified volunteer adult mentor through a comprehensive matching process, which emphasizes compatibility, commitment, and child safety. Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Bay Area enrolls young people 8–17 years old across all nine greater Bay Area counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma). The organization’s volunteer mentors are caring adults from a variety of backgrounds who want to be that extra source of consistency and inspiration for a Bay Area young person. For more information on enrolling a child or becoming a volunteer mentor, please visit bayareabigs.org.

Meet the Musicians

Jessica Valeri • Horn

Jessica Valeri joined the San Francisco Symphony horn section in 2008. She was previously a member of the St. Louis Symphony, Colorado Symphony, Grant Park Orchestra, and Milwaukee Ballet Orchestra. She holds degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Northwestern University.

How did you begin playing the horn?

I went to Catholic elementary school in Minneapolis, and we didn’t have a band program, so we were allowed to walk to the elementary school down the street to participate in their program. I wanted to play the trumpet, but I’m sure the teacher didn’t have enough horn players, so she said, “I really think you should play the French horn, it has a beautiful, rich, mellow, warm sound, and you have the perfect embouchure!” I fell for it, hook, line, and sinker!

What does it feel like playing on stage each week at Davies Symphony Hall?

When you walk out on stage, you can really feel the energy in the hall. Each audience is different, and we really do feel like we’re reacting to and participating with everyone here.

Do you have a concert day routine?

I usually eat an early dinner with my little one and my husband, Jonathan Vinocour, the Symphony’s principal viola. I don’t like rushing before the show. It takes time to get into the mood, have a solid warmup, and get settled in.

What kind of horn do you play?

My main horn is called a Kortesmaki, made by Karl Hill who lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He’s a one-man operation and it takes a very long time to get one. The craftsmanship is extraordinary and it was custom made for me, which is important as a woman, because most older horns are made and fitted for men. I also have an original Carl Geyer horn which was originally made for a low horn player. As a fourth horn, it is perfect for me to anchor the section.

What musical activities do you have outside the Symphony?

I teach at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and coached the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra for many years. In the summer, I often play at the Grand Teton Music Festival and Arizona Music Festival.

What do you do outside music?

I’m also a yoga teacher and lead a yoga and wellness class at the Conservatory. It seems like something there’s a need for; when I began the class, it immediately had a waitlist. I also train in martial arts with my young son.

What advice do you give young musicians about wellness?

Yoga is about showing up every day on the mat, and just by doing that, you can build a lot of awareness in your body about how you react to things. Then when you’re on stage, knowing what’s happening in your body and mind can make you a more authentic musician and more resistant to injury.

Print Edition