In This Program

- The Concert

- Program Notes

- Text and Translation

- San Francisco Symphony Chorus

- Pacific Boychoir Academy

- About the Artists

- Extended Reading

- About San Francisco Symphony

- Print Edition

The Concert

Friday, June 28, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, June 29, 2024, at 7:30pm

Sunday, June 30, 2024, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1896, rev. 1906)

Part I

Kräftig, entschieden (Powerful, determined)

Part II

Tempo di menuetto: Sehr mässig (Moderate)

Comodo, Scherzando, Ohne Hast (Not rushed)

Sehr langsam (Very slow), misterioso

Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck (Sprightly and audacious)

Sehr langsam und durchaus mit innigster Empfind (Very slow, and with great inner feeling throughout)

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Sopranos and Altos of the San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

Pacific Boychoir Academy

Andrew Brown director

This concert is performed without intermission.

These concerts are presented in honor of Robert and Kathleen Frost, who generously provided for the San Francisco Symphony through their estate.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Part I: We start with magnificent gaiety, but fall at once into tragedy—we hear see-sawing chords, drumbeats of a funeral procession, cries and outrage. The whole first movement is the conflict of dark and bright; the light triumphs.

Part II: This chapter features four shorter character movements. Delicately sentimental music contrasts with slightly sinister energies. First, Mahler draws on one of his own songs about waiting for Lady Nightingale to sing when the cuckoo is through. Then a human voice intones the “Midnight Song” from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra—imagine each of its 11 lines as coming between two of the 12 strokes of midnight. Soon the music surges forward and changes into a world of bells and angels. Text from German folk poems is interjected by “Du sollst ja nicht weinen” (But you mustn’t weep). A children’s chorus joins the ensemble. Mahler felt that his decision to end his symphony with a slow adagio was one of the most special he ever made. The immense final bars are intoned by thundering kettledrums. We’ve reached the end of this most riskily and gloriously comprehensive of Mahler’s worlds.

Symphony No. 3 in D minor

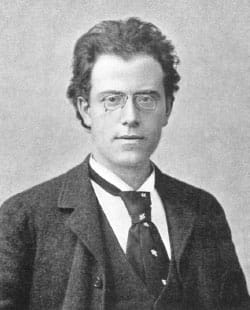

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, in Vienna

Composed: 1895–96 (rev. 1906)

SF Symphony Performances: First—May 1976. Seiji Ozawa conducted with the San Francisco Symphony Chorus, San Francisco Boys Chorus, and Lili Chookasian as soloist. Most recent—June 2018. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the San Francisco Symphony Chorus, Pacific Boychoir Academy, and Sasha Cooke as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo mezzo-soprano, chorus (sopranos and altos), boys’ chorus, 4 flutes (doubling piccolos), 4 oboes (4th doubling English horn), 5 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet, 4th playing E-flat clarinet, and 5th doubling E-flat clarinet), 4 bassoons (4th doubling contrabassoon), 8 horns, 4 trumpets, offstage post horn (cornet), 4 trombones, tuba, timpani (2 players), percussion (triangle, tambourine, cymbals, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, chimes, snare drum, bass drum, and glockenspiel), and strings

Duration: About 1 hour and 40 mins

When Gustav Mahler, then near to completing his Eighth Symphony, visited Jean Sibelius in 1907, the two composers talked about “the essence of symphony.” Mahler rejected his colleague’s creed of severity, style, and logic, saying that “a symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.” Twelve years earlier, while at work on the Third, he had remarked that to “call it a symphony is really incorrect as it does not follow the usual form. The term ‘symphony’—to me, this means creating a world with all the technical means available.”

The completion of the Second Symphony the previous summer had given him confidence, and he was sure of being “in perfect control” of his technique. Now, in the summer of 1895, escaped for some months from his duties as principal conductor of the Hamburg Opera, installed in his new one-room cabin at Steinbach on the Attersee some 20 miles east of Salzburg, with his sister Justine and his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner to look after him (this most crucially meant silencing crows, waterbirds, children, and whistling farmhands), Mahler set out to make a world to which he gave the overall title The Happy Life—A Midsummer Night’s Dream (adding “not after Shakespeare, critics and Shakespeare mavens please note”).

Before he wrote any music, he worked out a scenario in five sections, titled What the Forest Tells Me, What the Trees Tell Me, What Twilight Tells Me (“strings only,” he noted), What the Cuckoo Tells Me (scherzo), and What the Child Tells Me. He changed all that five times during the summer as the music began to take shape in his mind and, with a rapidity that astounded him, on paper as well. The Happy Life disappeared, to be replaced for a while by the Nietzschean Happy Science (first My Happy Science). The trees, the twilight, and the cuckoo were all taken out, their places taken by flowers, animals, and morning bells. He added What the Night Tells Me and saw that he wanted to begin with the triumphal entry of summer, which would include an element of something Dionysiac and even frightening. In less than three weeks he composed what are now the second, third, fourth, and fifth movements. He went on to the Adagio and, by the time his composing vacation came to an end on August 20, he had made an outline of the first movement and had composed two independent songs, “Lied des Verfolgten im Turm” (Song of the Persecuted Man in the Tower) and “Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” (Where the Lovely Trumpets Sound). It was the richest summer of his life.

In June 1896 he was back at Steinbach. Over the winter he had made some progress scoring the new symphony and had complicated his life by an intense and stormy affair with a young, superlatively gifted dramatic soprano newly come to Hamburg, Anna von Mildenburg. Now, as Mahler worked, he came to realize that the awakening of Pan and the triumphal march of summer wanted to be included in a single movement. He also saw, to his alarm, that the first movement was growing hugely, that it would be more than half an hour long, and that it was also getting louder and louder. He deleted his finale, What the Child Tells Me, which was the “Life in Heaven” song of 1892 and which he put to work a few years later to serve as finale to the Fourth Symphony. That necessitated rewriting the last pages of the Adagio, which had now become the finale, but essentially the work was under control by early August. The Happy Science was still part of the title at the beginning of the summer, coupled with what had become A Midsummer Noon’s Dream, but in the eighth and last of Mahler’s scenarios, dated August 6, 1896, the superscription is simply A Midsummer Noon’s Dream, with the following titles given to the individual movements:

First Part:

Pan Awakes. Summer Comes Marching In

(Bacchic procession)

Second Part:

What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me

What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me

What Humanity Tells Me

What the Angels Tell Me

What Love Tells Me

At the 1902 premiere, the program page showed no titles at all, only tempo and generic indications. “Beginning with Beethoven,” wrote Mahler to the critic Max Kalbeck that year, “there is no modern music without its underlying program.—But no music is worth anything if you first have to tell the listener what experience lies behind it, respectively, what he is supposed to experience in it.—And so yet again: pereat every program!—You just have to bring along ears and a heart and—not least—willingly surrender to the rhapsodist. Some residue of mystery always remains, even for the creator.”

Writing at about the same time to the conductor Josef Krug-Waldsee, Mahler elaborated:

Those titles were an attempt on my part to provide non-musicians with something to hold on to and with a signpost for the intellectual, or better, the expressive content of the various movements and for their relationships to each other and to the whole. That it didn’t work (as, in fact, it could never work) and that it led only to misinterpretations of the most horrendous sort became painfully clear all too quickly. It’s the same disaster that had overtaken me on previous and similar occasions, and now I have once and for all given up commenting, analyzing all such expediencies of whatever sort. These titles . . . will surely say something to you after you know the score. You will draw intimations from them about how I imagined the steady intensification of feeling, from the indistinct, unbending, elemental existence (of the forces of nature) to the tender formation of the human heart, which in turn points toward and reaches a region beyond itself (God).

Please express that in your own words without quoting those extremely inadequate titles and that way you will have acted in my spirit. I am very grateful that you asked me [about the titles], for it is by no means inconsequential to me and for the future of my work how it is introduced into “public life.”

The climate has changed over more than a century, and today’s audience is very much inclined to come to Mahler with that willingness to surrender for which he had hoped. We do well to ignore the “Titan” claptrap he imposed on his First Symphony—years after its composition; when, however, we look at the titles in the Third Symphony, even though they were finally rejected, we are looking at a series of attempts to put into few words the material, the world of ideas, emotions, and associations that lay behind the musical choices Mahler made as he composed. We too can draw intimations from them and then remove them as scaffolding we no longer need. That said, let us turn for a brief look at the musical world Mahler left us.

The Music

The first movement accounts for roughly one third of the symphony’s length. Starting with magnificent gaiety, it falls at once into tragedy—seesawing chords of low horns and bassoons, the drumbeats of a funeral procession, cries and outrage. Mysterious twitterings follow, the suggestion of a distant quick march, and a grandly rhetorical recitative for the trombone. Against all that, Mahler poses a series of brisk marches (the realization of what he had adumbrated earlier for just a few seconds), the sorts of tunes you can’t believe you haven’t known all your life and the sort that used to cause critics to complain of Mahler’s “banality,” elaborated and scored with an astonishing combination of delicacy and exuberance. Their swagger is rewarded by a collision with catastrophe, and the whole movement—for all its outside dimension as classical a sonata form as Mahler ever designed—is the conflict of the dark and the bright elements, culminating in the victory of the latter.

Two other points might be made. One concerns Mahler’s fascination, not ignored in our century, with things happening “out of time.” The piccolo rushing the imitations of the violins’ little fanfares is not berserk: it is merely following Mahler’s direction to play “without regard for the beat.” That is playful, but the same device is turned to dramatic effect when, at the end of a steadily accelerating development, the snare drums cut across the oompah of the cellos and basses with a slower march tempo of their own, thus preparing the way for the eight horns to blast the recapitulation into being. The other thing is to point out that several of the themes heard near the beginning will be transformed into the materials of the last three movements—fascinating especially when you recall that the first movement was written after the others.

In the division of the work Mahler finally adopted, the first movement is the entire first section. What follows is, except for the finale, a series of shorter character pieces, beginning with the Blumenstück, the first music he composed for this symphony. This is a delicately sentimental minuet, with access, in its contrasting middle section, to slightly sinister sources of energy. It “anticipates” music not heard in the symphony at all, specifically the scurrying runs from the “Life in Heaven” song that was dropped from this design and incorporated in the Symphony No. 4. Some time after he finished this movement, Mahler noted with surprise that the basses play pizzicato throughout. In the last measure, Wagner’s Parsifal flower maidens make a ghostly appearance in Mahler’s Upper Austrian pastoral.

In the third movement, Mahler draws on his song “Ablösung im Sommer” (Relief in Summer), whose text tells of waiting for Lady Nightingale to start singing as soon as the cuckoo is through. The marvel here is the landscape with post horn (performed this week on cornet by Associate Principal Trumpet Aaron Schuman), not just the lovely melody itself, but the way it is presented—the magic transformation of the very “present” trumpet into distant post horn, the gradual change of the post horn’s melody from fanfare to song, the interlude for flutes, and, as Arnold Schoenberg points out, the accompaniment “at first with the divided high violins, then, even more beautiful if possible, with the horns.” After the brief return of this idyll and before the snappy coda, Mahler makes spine-chilling reference to the “Great Summons” music in the Second Symphony’s finale.

Low strings rock to and fro, the harps accenting a few of their notes. The see-sawing chords from the first pages return; a human voice intones the Midnight Song from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra. Each of its 11 lines is to be imagined as coming between two of the 12 strokes of midnight. Pianississimo throughout, warns Mahler. The harmony is almost as static as the dynamics.

From here the music moves forward without a break and, as abruptly as it changed from the scherzo to Nietzsche’s midnight, so does it change now from that darkness to a world of bells and angels. The text of the fifth movement comes from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn), though the interjections of “Du sollst ja nicht weinen” (“But you mustn’t weep”) are Mahler’s own. A three-part chorus of soprano and alto voices carries most of the text, though the solo voice returns to take the part of the sinner. The children’s chorus, confined at first to bell noises, joins later in the exhortation “Liebe nur Gott” (Only love God) and for the final stanza. This movement, too, foreshadows the “Life in Heaven” that will not in fact occur until the Fourth Symphony.

Mahler perceived that the decision to end his symphony with an adagio was one of the most special he made. “In adagio movements,” he explained to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, “everything is resolved in quiet. The Ixion wheel of outward appearances is at last brought to a standstill. In fast movements—minuets, allegros, even andantes nowadays—everything is motion, change, flux.

“Therefore I have ended my Second and Third symphonies contrary to custom . . . with adagios—the higher form as distinguished from the lower.”

A noble thought, but, not uniquely in Mahler, there is some gap between theory and reality. The Adagio makes its way at last to a sure and grand conquest, but during its course—and this is a movement, like the first, on a very large scale—Ixion’s flaming wheel can hardly be conceived of as standing still. In his opening melody, Mahler invites association with the slow movement of Beethoven’s last quartet, Opus 135. Soon, though, the music is caught in “motion, change, flux,” and before the final triumph it encounters again the catastrophe that interrupted the first movement. The Adagio’s original title, “What Love Tells Me,” refers to Christian love, to agape, and Mahler’s drafts carry the superscription: “Behold my wounds! Let not one soul be lost!” The performance directions, too, speak to the issue of spirituality, for Mahler enjoins that the immense final bars with their thundering kettledrum be played “not with brute strength, [but] with rich, noble tone,” and that the last measure “not be cut off sharply”—so that there is some softness to the edge between sound and silence at the end of this most riskily and gloriously comprehensive of Mahler’s worlds.

—Michael Steinberg

Text and Translation

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 in D minor

Fourth Movement

O Mensch! Gib Acht!

Was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht?

Ich schlief!

Aus tiefem Traum bin ich erwacht!

Die Welt ist tief!

Und tiefer als der Tag gedacht!

Tief ist ihr Weh!

Lust tiefer noch als Herzeleid!

Weh spricht: Vergeh!

Doch alle Lust will Ewigkeit!

Will tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit!

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Take heed, humanity!

What does deep midnight say?

I slept!

I have awakened from a deep dream!

The world is deep—

deeper than the day had thought!

Deep is the pain!

Joy deeper still than heart’s sorrow!

Pain says: Vanish!

Yet all joy aspires to eternity,

to deep, deep eternity.

Fifth Movement

Es sungen drei Engel einen süssen Gesang,

Mit Freuden es selig im Himmel klang;

Sie jauchzten fröhlich auch dabei,

Dass Petrus sei von Sünden frei.

Denn als der Herr Jesus zu Tische sass,

Mit seinen zwölf Jüngern das Abendmal ass,

So sprach der Herr Jesus: “Was stehst du denn hier?

Wenn ich dich anseh’, so weinest du mir.”

“Und sollt ich nicht weinen, du gütiger Gott!”

Du sollst ja nicht weinen!

“Ich hab übertreten die Zehen Gebot;

Ich gehe and weine ja bitterlich.”

Du sollst ja nicht weinen!

“Ach komm und erbarme dich über mich!”

“Hast du denn übertreten die Zehen Gebot,

So fall auf die Knie und bete zu Gott,

Liebe nur Gott in alle Zeit,

So wirst du erlangen die himmlische Freud.”

Die himmlische Freud ist eine selige Stadt,

Die himmlische Freud, die kein End mehr hat;

Die himmlische Freud war Petro bereit

Durch Jesum und allen zur Seligkeit.

—from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Three angels sang a sweet song.

It resounded throughout heaven;

they also rejoiced

that Peter was free of sin.

For as the Lord Jesus sat down at the table

and ate the evening meal with his twelve disciples,

the Lord Jesus said, “Why are you standing here?

When I look at you, you cry.”

“And shouldn’t I cry, you kind God?”

You shouldn’t cry!

“I have broken the Ten Commandments;

I go and cry bitterly.”

You shouldn’t cry!

“Oh come, and have mercy on me!”

“If you’ve broken the Ten Commandments,

fall on your knees and pray to God.

Just love God always,

and you will have heavenly joy.”

Heavenly joy is a blessed city,

heavenly joy, which has no end;

heavenly joy was prepared for Peter

by Jesus, and for everyone’s salvation.

Translation by Larry Rothe

About the Artists

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

SOPRANOS

Adeliz Araiza

Naheed Attari

Sylvia V. Baba

Alexis Wong Baird

Morgan Balfour*

Arlene Boyd

Olivia T. Brown

Helen J. Burns

Laura Canavan

Sarita N. Cannon

Mun-Wai Chung

Francielle De Barros

Amy Foote*

Sara A. Frondoni

Cara Gabrielson*

Nina Groleger

Julia Hall

Betsy Johnsmiller

Kate Juliana

Jocelyn Q. Lambert

Becky Lau

Kyounghee Lee

Ellen Leslie*

Lane McKenna*

Aimée Puentes*

Hallie Randel-Schreiber

Natalia Salemmo*

Rebecca Shipan

Laura Stanfield Prichard

Sigrid Van Bladel

Sarah Vig

Lauren Wilbanks

Helene Zindarsian*

ALTOS

Terry A. Alvord*

Monica Lynn Baruch

Celeste Camarena

Carol Copperud

Shauna Fallihee*

Corty Fengler

Amy L. Hespenheide

Kelsey Ishimatsu Jacobson

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen A. Josaitis

Gretchen Klein

Donna Kulkarni

Linda Liebschutz*

Katherine M. Lilly

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Kimberly J. Orbik

Lindsay Marie Rader

Meredith Riekse

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Meghan R. Spyker*

Nicole Takesono*

Mayo Tsuzuki

Heidi L. Waterman*

Hannah Wolf

Jenny Wong

Chorus Director

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist

*Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists

Pacific Boychoir Academy

Founded in Oakland in 1998 by Artistic Director Kevin Fox, Pacific Boychoir Academy serves more than 150 choristers each season, has released nine independent albums, tours domestically and internationally, and has earned three Grammy Awards with the San Francisco Symphony.

Matt Ategeka

Dario Banuelos

Brett Colvin

Jacob Croteau-DeFreece

Tristan David

Kai Esainko

Brenn Farrel

Sam Gumas

Ethan Hajduk

Noah Hajduk

Oliver Hajduk

Bo Iverson

Alistair Lilly

Taz Lindheimer

Louis Lunt

Eli McKoy Beiser

James McLoughlin

Forrest “Mac” McNeil

Tenoch Meletiche

Andres Morales

Theo Moser

Giancarlo Padilla

Emmet Stout

Cadence Strange

Adrian Thong

Lucas Willcuts

Rory Wilmer-Child

Zachary Wilson

Andrew Brown, director

The San Francisco Symphony gratefully acknowledges the following donors who have made a recent contribution of $100 or more to the San Francisco Symphony Chorus through March 20, 2024.

Carolyn Alexander

Paul Angelo

Seth Brenzel & Malcolm Gaines

Ms. Vicki Coe

Corty & Alf Fengler

Mr. Richard M. Glendening

Ms. Amy L. Hespenheide

Elizabeth L. Hobson

Al Hoffman & David Shepherd

Insperity, Inc

Ms. Mary R. Jackman

Ms. Ann Jorgensen

The Keyes-Sulat Family Fund

Ms. Joyce Lin-Conrad

Yi & Chris Polczynski

Brian P. McCune

Mr. David Meders

Microsoft

Ms. Mary Pardue

Ms. Linda J. Randall

Jonathan H. Staley

Tom & Rosemary Tisch

Terry & Mary Vogt

Dan & Lauren Wilkins

Ms. Arden Wong

Anonymous

Esa-Pekka Salonen

San Francisco Symphony Music Director

Esa-Pekka Salonen is known as both a composer and conductor. He is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony, where he works alongside eight Collaborative Partners from a variety of disciplines, ranging from composers to roboticists. He is the conductor laureate of the Philharmonia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of the Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Mr. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival.

Beginning with the Opening Night Gala, Salonen leads the San Francisco Symphony in 12 weeks of programming in the 2023–24 season. Highlights include world premieres from Jesper Nordin, Anders Hillborg, and Jens Ibsen; projects by Collaborative Partners Pekka Kuusisto and Carol Reiley; the launch of the inaugural California Festival; a tour of Southern California; and a program of Ravel and Schoenberg featuring choreography by Alonzo King and staging by Peter Sellars.

He will also conduct many of his own works this season around the world. Among them are a new work commemorating the 20th anniversary of Walt Disney Concert Hall, premiering with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Karawane, also with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; his Sinfonia Concertante for Organ and Orchestra with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Philadelphia Orchestra; and kínēma with the San Francisco Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra.

Mr. Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

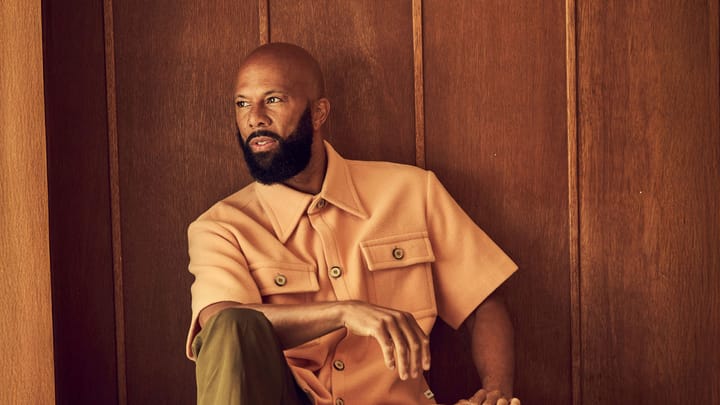

Kelly O’Connor

Grammy Award–winning mezzo-soprano Kelley O’Connor performs and inhabits a broad repertoire from Ludwig van Beethoven, Gustav Mahler, and Johannes Brahms to Bryce Dessner, John Corigliano, and John Adams. This season she performs with the Houston Symphony in Adams’s El Niño and brings Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs to the New World Symphony, Omaha Symphony, and the Auckland Philharmonia. She solos in Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Kansas City Symphony and she joins the Dallas Symphony for Franz Schmidt’s seldom-performed Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln. Additional performances this season included Handel’s Messiah with the Atlanta Symphony and Mozart’s Requiem with the Oregon Symphony. She appeared in the Bay Area with New Century Chamber Orchestra and in recital at Chamber Music in Napa Valley.

Ms. O’Connor has also appeared with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra Los Angeles Philharmonic, Minnesota Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, National Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, London Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Berlin Philharmonic, and Taiwan Philharmonic, among many others. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in April 2008.

Adams wrote the title role of The Gospel According to the Other Mary for Kelley O’Connor and she has performed the work both in concert and in Peter Sellars’s fully staged production. She continues to be the eminent living interpreter of Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs, and received critical acclaim for her performances in Oslvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar, including a Grammy Award for the Deutsche Grammophon recording with the Atlanta Symphony.

Her recording catalogue also includes Mahler’s Third Symphony with Jaap van Zweden and the Dallas Symphony, Lieberson’s Neruda Songs and Michael Kurth’s Everything Lasts Forever with Robert Spano and the Atlanta Symphony, Adams’s The Gospel According to the Other Mary with Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Franz Welser-Möst and the Cleveland Orchestra.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is the newly appointed Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, The Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles. She debuts this season with the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra.

Under Ms. Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, which won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance. She has also prepared choruses for the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and Music Academy of the West.

A native of Hong Kong, Ms. Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011.

Extended Reading

About San Francisco Symphony

- Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen

- San Francisco Symphony

- Calendar

- Celebrating Our Donors

- Volunteer Council

- Institutional Partners

- Board of Governors

- Administration

- Visitor FAQs

Print Edition