June 2024 Events at San Francisco Symphony

In This Program

- Welcome From the Chair

- News & Notes: In Celebration

- Movement as Metaphor: Alonso King

- Four Questions… for Violinist Stella Chen

- Meet the SF Symphony Musicians: Christina King

- Community Connections: The African American Art & Culture Complex

- Print Edition

Welcome

A successful San Francisco Symphony season depends on the contributions of so many. From Esa-Pekka Salonen and the talented musicians of our orchestra and chorus, to our dedicated board, volunteers, and staff, to our wonderful audience, everyone plays a crucial role in ensuring that the San Francisco Symphony continues to be a pivotal force in shaping our cultural landscape.

A look back at some of this season’s highlights reveals an incredible range of vital activities. We kicked off the season with a Gala performance that investigated the intersection of artificial intelligence and live performance, and Collaborative Partners Pekka Kuusisto and Carol Reiley led projects that innovatively integrated technology into our performances. We unveiled San Francisco Symphony commissions by Betsy Jolas, Jesper Nordin, Anders Hillborg, and Unsuk Chin, and helped launch a statewide festival showcasing music from the last five years, including performances of new works by Gabriella Smith and Emerging Black Composers Project winner Jens Ibsen. We also partnered with Cartier in a one-of-a-kind multisensory presentation of Scriabin’s Prometheus, The Poem of Fire, and collaborated with local visual artists to reinterpret Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

This season saw the addition of several new musicians who have already made a significant impact. Our San Francisco Symphony Chorus celebrated its 50th anniversary and welcomed a new director, Jenny Wong. And finally, we are excited about our collaborations this month with director Peter Sellars and choreographer Alonzo King, both of whom have brought innovative and moving work to our stage in recent seasons.

We have also strengthened our connection with audiences through initiatives such as our free Community Ticket Program and Community Chamber Concerts, and Music in the Wards, an outstanding collaboration with UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital.

Our longstanding partnership with San Francisco Unified School District continues to flourish through programs like Adventures in Music—our comprehensive free music education program for San Francisco’s public elementary school students—and Music and Mentors. Our tuition-free Youth Orchestra celebrated Daniel Stewart’s final season as music director, and events like our recent Teen Night concert introduced a new generation to the magic of the San Francisco Symphony.

While there are numerous other highlights from this season, each one serves as a reminder of the incredible creativity happening across our organization. None of this would be possible without the tremendous support and dedication of all who care deeply about the San Francisco Symphony. Thank you for keeping the music playing.

Priscilla B. Geeslin

Chair, San Francisco Symphony

In Celebration

News & Notes

With the close of the 2023-24 season, we bid farewell to five musicians retiring from the San Francisco Symphony.

Violinist Nadya Tichman joined the Orchestra in 1980, under Edo de Waart. She served as associate concertmaster from 1990 to 2022 and was also acting concertmaster from 1998 to 2001. Born in New York, she studied at the Juilliard School pre-college division and received a bachelor’s degree from the Curtis Institute of Music. She was a founding member of the Donatello Quartet and co-director of Chamber Music Sundaes, and had pieces dedicated to her by composers Peter Schickele, Jim Lahti, and Allen Shearer. Reflecting on the special chemistry of the musicians of the San Francisco Symphony, Tichman noted, “There are these times when everybody’s energy seems to line up. You can tell everybody is listening together, and is excited, and focused. We always play well of course, but there are certain times when you feel this thing becoming greater than the sum of the parts; where you all know. The greatest gift of my career in the Symphony has been making music with my incredible colleagues. Each one of them is an artist and contributes a unique voice to the whole.”

Violinist Amy Hiraga joined the San Francisco Symphony in 1999 under Michael Tilson Thomas. Previously, she spent one year as a member of the Symphony before returning to the East Coast with her husband, San Francisco Symphony cellist Peter Wyrick. She worked as a freelance musician in New York and joined the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in 1991. She has also been a member of the Orchestra of Saint Luke’s and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. She studied at the University of Cincinnati and the Juilliard School.

Peter Wyrick joined the San Francisco Symphony in 1999, served as Associate Principal Cello through the 2022–23 season, and currently holds the Lyman & Carol Casey Second Century Chair. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony multiple times, and has collaborated in chamber music with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. He has also played on the SF Symphony’s chamber music series at the Legion of Honor for many years.

Jill Rachuy Brindel, occupant of the Gary & Kathleen Heidenreich Second Century Cello Chair, joined the cello section of the San Francisco Symphony in 1980, under Edo de Waart. She studied at Indiana University and Chicago Musical College and was formerly assistant principal cello of the Lyric Opera of Chicago Orchestra, principal cello of the Mendocino Music Festival, and a member of the Houston Symphony. She has also served as a coach for the cello section of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra. A member of the Navarro Trio for more than 30 years, Brindel reflected on the difference between playing chamber music and orchestral music: “I really enjoy playing in the cello section here; we have a wonderful camaraderie. I like to be able to have my own voice, which is why I enjoy chamber music. But in an orchestra, you’re lost in this mass of sound, and sometimes that is exactly what I like about it. It is egoless; you really lose your sense of self, which is a wonderful feeling.” Following her retirement, she will continue as a coach for the Youth Orchestra, in addition to teaching privately and at Sonoma State University.

Steven Dibner has served as Associate Principal Bassoon of the San Francisco Symphony since 1983. In his New York years, he played for Frank Sinatra in Carnegie Hall, with Plácido Domingo at the Met, for Linda Ronstadt on Broadway, and with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. He also toured and recorded extensively with Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. After arriving in San Francisco, Dibner created and conducted a chamber orchestra featuring his San Francisco Symphony colleagues called PARLANTE. With the Symphony, he appeared as a soloist under Herbert Blomstedt and Yehudi Menuhin, and once sang a Mozart aria with the Orchestra. Summers have found Dibner teaching, coaching, and concertizing in Aspen or Marlboro, and he has also regularly coached the wind players of the New World Symphony. In his retirement, he looks forward to pursuing his passions for cooking and baking, volunteering at the Dahlia Dell in Golden Gate Park, and watching Jeopardy! “Having joined the orchestra 40 years ago, I have now played under four music directors,” Dibner said. “I feel like a living link—early in my San Francisco career, I performed alongside legendary musicians like flutist Paul Renzi, who played for Toscanini; hornist Dave Krehbiel, whose sound I had grown up with in the Detroit Symphony; and oboist Marc Lifschey, whose playing I adored from Cleveland Orchestra recordings under George Szell. Now, I’m trying to keep up with the young stars in our orchestra!”

We thank these wonderful musicians for their many years of service to the San Francisco Symphony and we wish them well.

Movement as Metaphor

Choreographer Alonzo King on motion, sound, and fairy tales

by Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

One of Alonzo King’s earliest memories is of his mother preparing to go out one evening. She was wearing a dress made of a fabric that whispered at every step, and as its chiffony rustle blended with the sweetness of her voice, he experienced her presence as both motion and sound. “They’re really the same,” he said in a video interview from his San Francisco home, “because you can’t make sound without some kind of movement.”

King is one of the most innovative choreographers in America, dedicated to dance as a form of spiritual inquiry that fuses sound and movement with love. In a workshop that has garnered tens of thousands of views online, he once defined ballet as “a system of law and order that has to do with kindness, benevolence and symmetry.”

This month, dancers from the Alonzo King LINES Ballet will join the San Francisco Symphony for a new staging of Ravel’s Mother Goose conducted by Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen. In previous collaborations, King has reached far afield to work with Shaolin monks, Baka hunter-gatherers from the Congo Basin, or with the tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain for a Sheherazade that reimagined Rimsky-Korsakov’s tunes on Persian instruments. But though only a few blocks separate King’s company from Davies Symphony Hall, this new work, too, speaks to King’s ongoing efforts to integrate East and West.

In classrooms, Ravel’s collection based on French fairy tales sometimes serves as a textbook case of Orientalism. Dainty pentatonic scales and shimmering sonorities color the movement about “Laideronnette, Empress of Pagodas”—the musical fetishization of an effeminate Other. But for King, East and West are complimentary qualities inherent in every human. “That’s the beauty,” he said. “It’s in us. It’s left brain, right brain. It’s logic and feeling.” The power of dance, for him, lies in its ability to bring out the inherent wisdom of the human body. Alignment is not just an aesthetic goal or muscular challenge. It models balance in a world that teeters between unhealthy extremes.

“We know that on the lowest level, logic can be humdrum, predictable, stuck,” King said. “On the lowest level, feeling can be indulgent, illegible—you know: muck.”

In King’s choreographies, every movement is metaphor. When rehearsing with dancers, he speaks of arms as antennae that receive and give information and of the heart as a sun that should radiate warmth. Extensions might speak of the human yearning for eternity; a spiral might be the head chasing the tail. Ballet, he once said, is a treatise on how to lead a complicated life.

King’s engagement with Indian philosophy goes back to his childhood in Georgia. His parents were Civil Rights activists, his father a leader of the Albany Movement and a committed disciple of Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent protest. King remembers visits from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, as well as from friends from Ethiopia, Ghana, and Senegal who brought with them their own music that blended with the recordings of Bach, Beethoven, and Wagner, which his parents, who had met in the choir at Fisk University, loved to play. In church, he sang in the choir, feeling himself drawn to “all the beautiful chorales that had that Gregorian chant in them, which actually spoke of the East as its origin and how deep and profound that was.”

One room in the home was dedicated to yoga, which King’s father practiced. He would invite the children to observe, quietly, for five minutes at a time. With his brother and sister, King said, he would “go in and imitate lotus posture, and we’d look at each other and giggle and try to be quiet. And then after what we perceived to be five minutes, we would tiptoe out.” He said these early encounters planted the seed for his own lifelong engagement with meditation and spiritual study. “As contradictory as it may seem for someone who grew up a mover,” King said, “stillness is the doorway to peace. A body that’s not flinching, a body that you don’t scratch when you feel an itch, a mind that isn’t restless—that’s the door to the Divine.”

For his company, he hires dancers as much based on character as on their athleticism. A signature of his style is an uncanny quality of simultaneous fluidity and calm, with limbs that seem to unfold like a natural process, with inevitability and ease. Lines morph into waves as arms stretch and undulate.

“They really begin to see it as an instrument,” King said of his dancers’ relationship to their bodies. “They begin to work it as a violin, as a piano, as a harpsichord. It’s music. And what’s really playing that instrument is the mind and the heart. And as you’re playing, whether it’s choreography or as a composer, you’re trying to find the essence of the communication, the ideas that are behind the music or the choreography. And you want them to inhabit you so that they’re clear.”

In the case of Ravel’s Mother Goose, King said he tries to connect to the archetypes beneath the children’s tales, which include well-known stories like Sleeping Beauty and Tom Thumb. Although Ravel’s music was not initially designed for the stage, the music conveys a strong sense of movement, with sections including a waltz, a lullaby, a pavane, and a spinning-wheel dance. King’s choreography is not so much about telling the stories, he said, as it is about teasing out what he sees as the work’s underlying metaphysical truths. And, as always, the key lies in the symbolism of the body itself.

“Take the princess in Sleeping Beauty,” he said. “What is that if it’s not all of us who are walking around in some state of unconsciousness? And we’re awakened by the magic wand— which is the spine, which means willpower—into a larger consciousness.”

Esa-Pekka Salonen and the San Francisco Symphony’s concerts on June 7–9 pair Ravel’s Mother Goose, with LINES Ballet performing new choreography by Alonzo King, and Schoenberg’s Erwartung, sung by soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams in a new staging by Peter Sellers. “Alonzo is a master choreographer with a very unusual sensitivity towards music,” Salonen said. “His dancers are amazing and somehow everything is organically connected to the flow of the music.” Speaking of his longtime collaborator Peter Sellars, Salonen observed “Besides his brilliant conceptual thinking, Peter has this quite rare craft of working with people. It’s a process that is absolutely fascinating to follow.”

While contemporaries, Schoenberg and Ravel inhabited vastly different realms, both in terms of musical style and their imaginative approaches to storytelling. Mother Goose is a favorite of Salonen: “With very few notes, Ravel creates a perfect universe where everything is exactly as everything should be, like a better world. It’s almost magic.” Of Schoenberg’s monodrama Erwartung, Salonen said “It’s kind of a mysterious piece because we don’t quite know what’s going on. And so it basically leaves the field wide open for interpretation. That’s where Peter Sellars comes in.”

Four Questions for… Violinist Stella Chen

Tell us a little about what you’re playing in your Spotlight Series recital with George Li.

We’ll begin the program with Schubert’s spectacular B-minor Rondo, which catapults right out of the gate with a declamatory announcement from the piano, joined by blisteringly fast rocketing scales in the violin. After taking a quick turn into one of those gorgeous Schubertian melodies that make you smile and cry at the same time, we race off into the rondo, with rarely a second to catch your breath as we dart and dash playfully all the way to the end.

This is followed by Eleanor Alberga’s No-Man’s-Land Lullaby, which is a piece I discovered in 2020 and have been in love with ever since. It’s based on poems written on the experience of being in the trenches during the world wars, and is dynamic, even violent at times, and desperate. All the while it is haunted by the fragments of a melody that pervades through, which we don’t hear in its complete form until the end of the piece, but it’s one that we will all recognize.

We end with Beethoven’s epic Kreutzer/Bridgetower sonata, a piece that may need no explanation. It’s a pinnacle of his duo sonatas, full of drama, virtuosity, playfulness, tender love, and everything in between.

What’s your process for preparing for a concert and how do you know when a piece is ready for an audience?

Luckily, my answer to this one is simple: My relationship with any great piece will be a lifelong journey. The longer I get to spend with a piece or a program, the better. But every performance of a piece will be special in its own way—each with its own unique perspective, circumstances, audience, venue, energy—yet all with the utmost love and joy to share in the music and the experience together.

Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in classical music?

There have been many people and pivotal points in my life that gave me the courage to pursue a career in classical music. First was going to the Perlman Music Program as a teenager. Not just having lessons and playing chamber music, but spending seven weeks every summer having lunch, playing pool, and just being around Itzhak and Toby Perlman and all the young, passionate musicians all day every day was transformative.

The other moment I’ll mention is hearing Robert Levin talk about the Schubert G-major Quartet when I was taking his class at Harvard. The way he spoke about this piece, which brought tears to my eyes despite never having heard it, sparked my lifelong love of Schubert. The Schubert Fantasie became a monumental piece for me—that story will have to wait for another time.

What are some of your interests outside of music and how do they influence your creativity and artistic expression?

I have long been a fan of figure skating, having been a terrible amateur skater myself for half a decade. The aesthetic beauty of the lines that the top skaters create is absolutely spellbinding, not to mention the athleticism and finesse required to create that much torque and hurl yourself into the air, rotate 3-4 times before landing perfectly on one leg. There is also a constant debate in the skating world on how much to reward jumps/stunts, per se, as opposed to beautiful skating quality, choreography, etc.—essentially all deemed the “artistic side.” This is a dichotomy of which the hierarchy seems so clear to me in music (athleticism in service of the art), and it’s fascinating to observe in skating.

Christina King, Viola

Meet the SF Symphony Musicians

Christina King joined the San Francisco Symphony in 1996 and was previously a member of the Tucson Symphony and principal viola of the Civic Orchestra of Chicago. A native of Newport Beach, California, she holds degrees from Barnard College and Northwestern University.

Do you remember the first concert you played with the San Francisco Symphony?

I don’t recall my very first concert, but I remember the first few weeks I played next to our former principal viola, Geraldine Walther. Part of the tenure process is having section players sit with the principal at the first desk. We played Mahler 10 with MTT—it felt like a trial by fire! One of my first tours was also very memorable, when we played Rite of Spring at the BBC Proms. There’s a video of that performance on YouTube. It has an electric energy, and it was just an incredible experience to play there.

How did you begin playing viola?

I grew up in a musical family. Everyone played piano and we were given the option to choose another instrument. I chose violin when I was eight and switched to viola in college. I loved the sound and the slightly more laidback feeling of being the middle voice instead of always playing first violin. I didn’t know if I wanted to go into music, so I went to Barnard College and was an English major while also studying at Manhattan School of Music.

Did your interest in English tie into music, or contribute to your playing?

Great question. I received a liberal arts education and had a lot of courses in art history and languages. I really feel like that supported my music later. Being able to look at paintings and know what was happening in different time periods also affects how you interpret music and how you feel about it.

Can you tell us about your viola?

It’s by a modern American maker named Benjamin Ruth. I would’ve loved to purchase an older instrument, but I couldn’t find one that suited me and that I could afford. I was working with a woman at a string instrument dealer in Boston, and it turned out she was married to a maker. She recommended him, and I told him what size and style of instrument I was in love with. It’s a copy of a 17th-century Maggini. . . he antiqued it, and it has a double purfling and a special design on the back. It’s quite beautiful and a great instrument.

Is there a breaking-in process with a brand-new instrument?

Yes, absolutely. Usually a new instrument sounds kind of green, and it’s very hard to predict how it will develop. As the wood changes and everything settles in, it could sound worse in a year, or it could sound better and better. In my case, it all worked out.

What about your bow?

I have two bows at the moment. One by Émile Ouchard, it’s a beautiful 20th-century French bow. The other is an English bow by James Tubbs that I purchased from a colleague who retired. So that bow was played in the Symphony before, and I was fortunate enough to buy it. They have different feels and are better for different styles.

How do you spend time outside of work?

I became really involved with triathlon, so a lot of my free time is spent swimming, biking, and running. It’s my alternate universe, my alternate passion. I think it supports my health and fitness and my ability to keep doing the job—playing in the orchestra is very demanding, both physically and mentally. I also have a Australian labradoodle named Teddy. He’s a love.

Do you ever have a chance to sit in the audience?

(Laughs) I do. Sometimes if I’m not playing a piece, I’ll go in the hall. When you work with the same people for many years, they’re just like family members, and you can hear how they come together to create the whole character of the sound. It’s a wonderful, wonderful group of people.

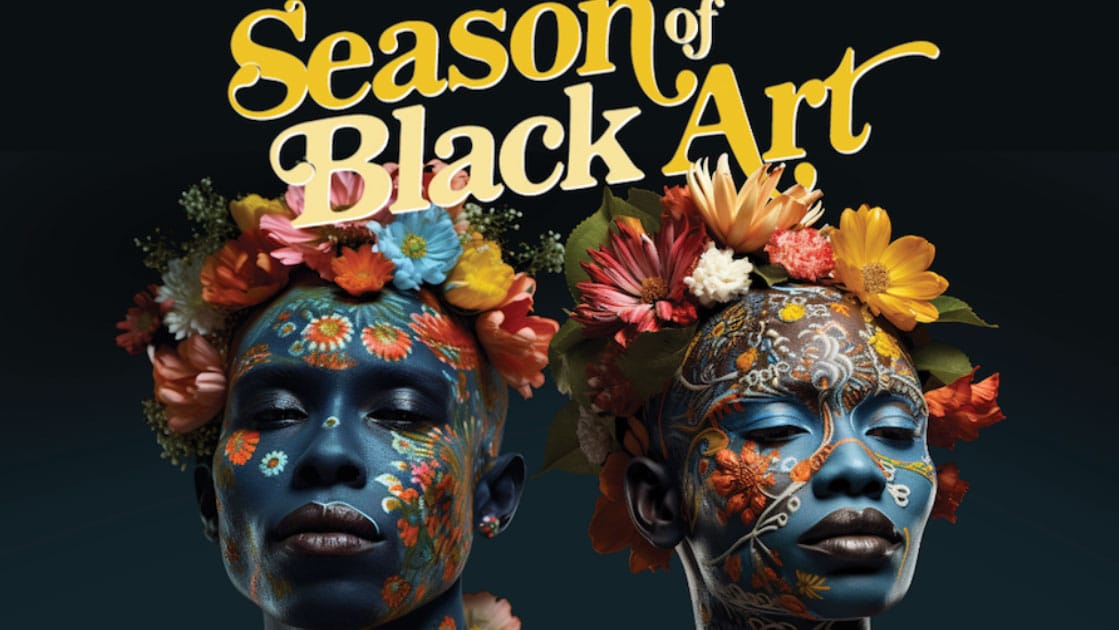

The African American Art & Culture Complex

Community Connections

The African American Art & Culture Complex (AAACC) is a beacon of hope and resilience in the vibrant tapestry of San Francisco. More than just an arts organization, it is a sanctuary for belonging, a hub of creativity, and a home and holder of Black dreams.

The AAACC fuels dreams to shape better realities and drive positive change. Through strategic collaborations, it empowers Black creatives and entrepreneurs with the support and resources needed to thrive. By fostering an inclusive ecosystem for their projects and products to flourish, the organization celebrates art and culture while challenging systemic barriers by facilitating networking opportunities, regranting, and fiscal sponsorships.

The AAACC began partnering with Tree of Change in 2023 to create a platform for reflection and visioning with the community. Through dreaming sessions, the Black Dreams Archive was born. This one-of-a-kind living archive is a commitment to preserving the cultural heritage of the African diaspora in San Francisco. The AAACC continues to grow this initiative, welcoming more Black creatives to engage with the project.

The African American Art & Culture Complex is on a transformative journey to boldly speak truth to power and stand against all forms of injustice. It is creating a future where every dream is valued, every voice is heard, and every individual feels welcomed.

The San Francisco Symphony thrives on collaboration, and we’re proud to work with the most creative, innovative groups and individuals shaping the Bay Area today.

Print Edition