In This Program

The Concert

Saturday, March 8, 2025, at 7:30pm

Edwin Outwater conducting

San Francisco Symphony

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Elliott James-Ginn Encarnación guest director

San Francisco Conservatory of Music Orchestra

Aaron Copland

The Promise of Living from The Tender Land (1954)

First San Francisco Symphony Performance

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Elliott James-Ginn Encarnación guest director

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Opus 18 (1901)

Moderato

Adagio sostenuto

Allegro scherzando

Garrick Ohlsson

Intermission

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Opus 95, From the New World (1893)

Adagio–Allegro molto

Largo

Scherzo: Molto vivace

Allegro con fuoco

This benefit concert is presented by the San Francisco Symphony, the Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Net proceeds from this concert will be split evenly and donated to two vital organizations providing essential relief services for victims of the Los Angeles fires:

Entertainment Community Fund

Habitat for Humanity of Greater Los Angeles: ReBUILD LA

Program Notes

The Promise of Living from The Tender Land

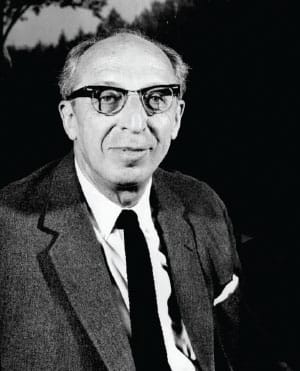

Aaron Copland

Born: November 14, 1900, in New York

Died: Decembe 2, 1990, in North Tarrytown, New York

Work Composed: 1952–54

First SF Symphony Performance

Instrumentation: chorus, 2 flutes, oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, percussion (tubular bells and cymbals), harp, celesta (doubling piano), and strings

Duration: About 5 minutes

Aaron Copland’s opera The Tender Land premiered in 1954 at New York City Opera in a production directed by Jerome Robbins. Two decades earlier, Copland had shifted toward writing American Gebrauchsmusik (a German term popularized by Paul Hindemith meaning “music for use”). Within this ethos, Copland created appealing and functional music: often for the stage, to be performed and appreciated by amateurs, and drawing from American musical traditions, especially folk tunes.

Copland originally intended The Tender Land to premiere on television, but NBC producers rejected the piece. He had been inspired to write an opera after reading James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Men (1941), which documents the lives of three sharecropper families living in Alabama during the Great Depression. Agee described it as a book “for those who have a soft place in their hearts for the laughter and tears inherent in poverty viewed at a distance. . . in hope that the reader will be edified, and may feel kindly disposed toward. . . efforts to rectify the unpleasant situation.”

Set over the course of 24 hours, The Tender Land opens at dawn the day before Laurie Moss’s high school graduation, which coincides with the spring harvest, an important time for the Moss family. When two itinerant workers show up, Laurie unexpectedly falls in love with one, Martin, whose solo opens “The Promise of Living,” which closes Act I.

Originally a quintet, Copland rescored the number for chorus shortly after the opera’s premiere. Accessible to any group from high school to professional choirs, it has become a popular selection to uplift and inspire, and its inclusion on this benefit concert resonates with Copland’s Gebrauchsmusik ideal. As Horace Everett’s libretto goes: “The promise of growing with faith and with knowing is born of our sharing our love with our neighbor.”

—Kate McKinney

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Opus 18

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born: April 1, 1873, in Semyonovo, Staraya Russa, Russia

Died: March 28, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California

Work Composed: 1900–01

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1926. Alfred Hertz conducted with Henri Deerng as soloist. Most recent—July 2023. Anna Rakitina conducted with Denis Kozhukin as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 32 minutes

At the head of of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto stands the simple dedication, “À Monsieur N. Dahl.” Monsieur Dahl was actually Dr. Nicolai Dahl, an internist who had been studying hypnosis. Rachmaninoff began daily visits to him in January 1900 to resolve a case of writer’s block following the disastrous premiere of his First Symphony. Dahl’s treatment, a mixture of hypnotic suggestion and cultured conversation, did its work. By April Rachmaninoff felt well enough to travel to Crimea and on to Italy. When he returned home, he brought with him sketches for the new piano concerto. Two movements, the second and third, were finished that fall and introduced in December. After the concert, Rachmaninoff added the first movement. Five days before the premiere in November 1901, he suffered a moment of panic and was convinced he had produced a totally incompetent piece of work, but the tempestuous success he enjoyed at the premiere seems to have convinced him otherwise.

The Music

A quality especially apparent in the Second Piano Concerto is a sense of effortlessness in its unfolding, and that is something new in Rachmaninoff’s music. He begins magnificently, and with something so familiar that we come perilously close to taking it for granted—a series of piano chords in crescendo, all based on F, each reinforced by the tolling of the lowest F on the keyboard, and, through the gathering harmonic tension and dynamic force, constituting a powerful springboard for the move into the home chord of C minor. Once there, the strings with clarinet initiate a plain but intensely expressive melody, which the piano accompanies with sonorous broken chords. The piano’s role as accompanist is also worth noting. Nowhere is the pianist so often an ensemble partner and so rarely a soloist aggressively in the foreground as in this first movement of the Second Concerto. The initial impulse plays itself out in one grand, tightly organized paragraph, to which Rachmaninoff appends two small afterthoughts, a bit of scurrying for the piano and a quite formal set of cadential chords. It is only then that the orchestra falls silent and the pianist steps forward as a vocal soloist in the grand Romantic manner.

Rachmaninoff constructs a bridge passage into the second movement. Again the pianist is at first the accompanist, briefly to the flute, at greater length to the clarinet. Throughout the movement the relationship between piano and orchestra is imagined and worked out with great delicacy. There is something captivatingly touching about the way the piano shyly inserts just six notes of melody between the first two phrases of the clarinet, the roles of piano and orchestra being reversed later in the movement. A quicker interlude functions as a token scherzo. This interlude spills into a splash of cadenza, and for just five notes a pair of flutes eases the music back into softly swaying arpeggios.

Rachmaninoff again makes a bridge into the finale, beginning with distant, rather conspiratorial march music, then working his way around to the piano’s assertive entrance. The march music is now determined and vigorous, and Rachmaninoff finds for contrast the most famous of his big tunes. It all moves to a rattling bring-down-the-house conclusion. When one remembers the biographical background to this concerto, it is pleasing to see that the last tempo mark is risoluto.

—Michael Steinberg

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Opus 95, From the New World

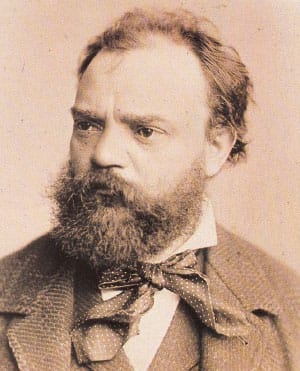

Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died: May 1, 1904, in Prague

Work Composed: 1892–93

SF Symphony Performances: First—October 1912. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—January 2024. Dalia Stasevska conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle and cymbals), and strings

Duration: About 40 minutes

The rise of musical nationalism in the 19th century was based on the idea that each nation has folksongs that are inherently their own, and the job of a composer was to discover, develop, and refine these songs into a national classical music. This was especially relevant to Czech composers, as an ongoing National Revival was redrawing cultural distinctions between themselves and their Austrian neighbors after centuries of common Habsburg rule.

Americans, too, began to wonder if they should have classical music of their own. In 1885 the New York philanthropist Jeannette Thurber founded the National Conservatory of Music and in 1892 recruited Antonín Dvořák to be its director. She hoped he would educate local musicians and advance a national style much like he had in his homeland of Bohemia. In the words of H. L. Mencken, he was hired to “introduce Americans to their own music.”

One of the students at the National Conservatory was Harry T. Burleigh, a Black Pennsylvanian composer and singer who showed Dvořák a variety of American folk styles. While recognizing the ethnic and cultural diversity of Americans, Dvořák concluded that American classical music should draw primarily from African American spirituals as well as the music of American Indians. He wrote: “These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

And so he wrote the New World Symphony and American String Quartet as models, loosely integrating elements of African American and Native American musical traditions. The Symphony was premiered by the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall on December 16, 1893, conducted by Anton Seidl, and was immediately met with acclaim. But the Panic of 1893 had left the National Conservatory’s finances—and Dvořák’s expensive salary—in jeopardy. He returned to Bohemia in April 1895, penning a bitter goodbye in Harper’s Magazine lamenting the paltry support for concert music in America.

The Music

There are no genuine American folk tunes in the New World Symphony—just elements of what Dvořák thought made them distinctive: pentatonic (five-note) scales, drumming patterns, and syncopated rhythms. The middle movements were partly inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, a romanticized epic poem about Native Americans. And Dvořák’s own Czech style still shines through the piece, even as he tried to overlay it with American elements.

The first movement begins with an Adagio introduction that paints a hazy scene. Then the faster Allegro molto section introduces a bold call-and-response pattern, first heard between the horns and woodwinds. A second theme appears with the flute and oboe playing quietly together in a pentatonic scale. The last theme to be introduced is a lyrical flute solo reminiscent of the spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which Burleigh taught to Dvořák. All these elements are mixed together and recur throughout the movement.

The slow movement, Largo, begins with seven mysterious chords that connect into a famous English horn solo. This, too, resembles a traditional spiritual or hymn, but the melody is entirely by Dvořák. (In 1922, one of his students added lyrics, creating the popular song “Goin’ Home,” sometimes mistaken as the original source.) Much of the movement develops the tune, including a striking passage where it’s accompanied by a pizzicato walking bass line. After a contrasting section that brings back the opening theme of the first movement, the English horn melody returns and grows warmer with strings.

The third movement, Vivace, begins with a clipped falling pattern suspiciously similar to the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The music here is dancelike, inspired by Hiawatha’s wedding feast in the Longfellow poem.

The finale, Allegro con fuoco, opens with a tense rising half-step pattern in the strings, building to a powerful brass fanfare, and then a second theme in the clarinet. The movement brings back earlier melodies—including “Goin’ Home”—before arriving at a coda and a blaring E-major ending. But in a final touch evoking America’s open landscapes, Dvořák adds an echo that fades into silence.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

About the Artists

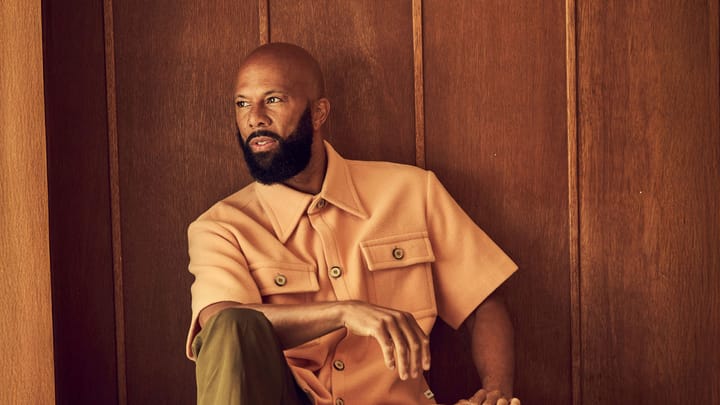

Edwin Outwater

Edwin Outwater regularly works with the world’s top orchestras, institutions, and artists to reinvent the concert experience. His ability to cross genres has led to collaborations with Metallica, Wynton Marsalis, Renée Fleming, and Yo-Yo Ma. He is music director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and music director laureate of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony.

Recent appearances include the New York Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Diego Symphony, Seattle Symphony, and the New World Symphony, as well as the Royal Philharmonic in a multi-concert series opening the Steinmetz Hall in Florida. He also served as a producer and musical advisor for the National Symphony Orchestra’s 50th Anniversary Concert at the Kennedy Center. In December 2022, he premiered A Christmas Gaiety at the Royal Albert Hall with Peaches Christ and BBC Concert Orchestra, and returned in 2023.

Outwater has held a long association with San Francisco Symphony since making his debut in November 2001, having served as Resident Conductor, Director of Summer Concerts, and Music Director of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra.

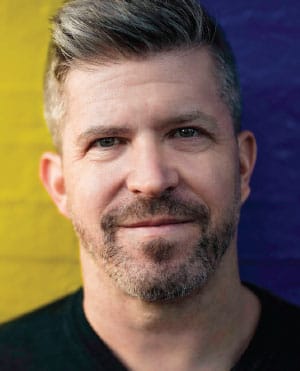

Garrick Ohlsson

Since his triumph as winner of the 1970 Chopin International Piano Competition, Garrick Ohlsson has established himself worldwide as a musician of magisterial interpretive and technical prowess. Although long regarded as one of the world’s leading exponents of the music of Frédéric Chopin, Ohlsson commands an enormous repertoire which ranges over the entire piano literature encompassing more than 80 concertos.

This season, Ohlsson appears with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Oregon Symphony, Kalamazoo Symphony, Palm Beach Symphony, and Fort Worth Symphony. Collaborations with the Cleveland, Emerson, Tokyo, and Takács quartets have led to decades of touring and recordings, and his solo recordings are available on Hyperion and Bridge Records.

Ohlsson studied at the Juilliard School and was awarded the Avery Fisher Prize in 1994 and the University Musical Society (University of Michigan) Distinguished Artist Award in 1998. He was the 2014 recipient of the Jean Gimbel Lane Prize in Piano Performance from Northwestern University, and in August 2018, the Polish government awarded him the Gloria Artis Gold Medal for Cultural Merit. He is a Steinway Artist and lives in San Francisco, where he serves on the piano faculty of SFCM. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in May 1972.

San Francisco Conservatory of Music

The San Francisco Conservatory of Music is advancing a new model of music education that sets students up for a rewarding career in music and a path of lifelong learning. With partnerships with artist-management companies Opus 3 and Askonas Holt and record label Pentatone, and its faculty, facilities, and position at the heart of the San Francisco music scene, there is no music school with a comparable ability to prepare—and define—the 21st-century musician.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8), Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8), and most recently Best Opera Recording (for Saariaho’s Adriana Mater).

Elliott James-Ginn Encarnación

Guest chorus director Elliott James-Ginn Encarnación is a composer and conductor of choral and operatic repertoire. As a self-taught tenor, he has appeared as a soloist with the San Francisco Symphony, California Bach Society, Dessoff Choirs, Long Island Symphony Choral Association, and Musica Sacra. His compositions and performances can be heard frequently in choral contexts with premier choral ensembles in New York, Santa Fe, and the Bay Area, and he has recorded for the Delos and Decca labels. He has served as artistic director for the Opera Theater Unlimited and Prodigal Opera Theatre, and as composer in residence for the International Orange Chorale in San Francisco.

Special Guest Soloists

Mezzo-soprano Nikola Printz was an Adler Fellow with San Francisco Opera and a member of the Merola Opera Program. They recently sang Carmen in SF Opera’s Carmen Encounter, and have also appeared with Opera San Jose, Opera Memphis, Pocket Opera, and West Edge Opera. An SFCM graduate, they made their San Francisco Symphony debut in 2022.

Tenor Christopher Oglesby was an Adler Fellow with San Francisco Opera, where he has sung multiple roles, and has recent and upcoming appearances with Calgary Opera, Opera Maine, Sarasota Opera, Grand Teton Music Festival, and Utah Opera. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this concert.