June 2, 2024 | Gunn Theater, California Palace Legion of Honor

In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, June 2, 2024, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Trio in E major, K.542 (1788)

Allegro

Andante grazioso

Allegro

Richard Strauss

Cello Sonata in F major, Opus 6 (1883)

Allegro con brio

Larghetto

Allegro vivace

Intermission

Bedřich Smetana

Piano Trio in G minor, Opus 15 (1855)

Moderato assai

Allegro, ma non agitato

Presto

Program Notes

Piano Trio in E major, K.542

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Composed: 1788

In the early piano trios of Franz Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the cello mostly doubled the bass line played by the pianist’s left hand. Everything changed in the 1780s, when the cello achieved full citizenship in the ensemble. During that decade, both Haydn and Mozart embarked on the extraordinary trios of their maturities. Mozart was under considerable financial duress in 1788, when he wrote three trios (K.542, K.548, and K.564), and he surely hoped they would meet with commercial success.

They relate to a golden moment in Mozart’s career. The trios of 1788 were interlaced among the creation of his last three symphonies. It is so astonishing to realize that the last three symphonies together were composed that summer over a span of only about nine weeks that we can scarcely imagine how during that time he also composed other pieces. He completed his E-major trio only four days before his Symphony No. 39, entering it in his catalogue on June 22. He was apparently working on them simultaneously. In a letter to his friend Michael Puchberg that June, Mozart proposed playing the E-major trio at Puchberg’s home, which he probably did shortly after the piece’s completion. He certainly presented it on April 14, 1789, at the Dresden court.

The piano is “first among equals” in the E-major trio, seeming not far removed from what we would expect of a Mozart piano sonata, but the string parts are also remarkably independent, even if they are ultimately less challenging. Notwithstanding its quick tempo marking, the opening Allegro has a leisurely aspect; its first theme, which the piano spells out mostly in quarter notes, must be played at a rather relaxed pace if the 16th-note runs that emerge a bit later are to be rendered without breaking the overriding tempo. Before we get to that, however, we should bask in the repetition and elaboration of that opening theme with a varied and enlarged sense of orchestration. A spectacular moment in the history of the independence of the cello comes with that instrument’s expansive statement, in the working-out of the movement’s arpeggio-intensified second theme, of a phrase that bravely steers the music into distant harmonic climes.

The middle movement is a sort of rondo (its interludial episodes being clearly derived from the rondo theme itself) that seems unpromising at first; its principal theme is a slight and harmonically static tune that sounds like a French romance of the time, maybe the sort of ditty Marie Antoinette might have sung while playing at being a shepherdess in the back-acreage of Versailles. But doubts are swept aside as the movement progresses, and Mozart discovers dramatic possibilities few could have imagined in this unassuming melody.

He sketched 65 measures of a finale in 6/8 meter before consigning that effort to his pile of incompletions and starting afresh with the finale that would become permanent, an Allegro in cut time. The statement of the rondo theme is marked dolce in the score, a marking that concurs with the tune’s unassuming nature but that proves difficult to sustain as the movement develops with concerto-like virtuosity, particularly in the piano and violin parts. Mozart also works a clever structural variant into this movement. Where a rondo by definition involves the alternation of a refrain with contrasting sections (yielding the plan of A–B–A–C–A–D–A. . . with as many interpolated contrasting sections as a composer wants), here Mozart tweaks the standard form to provide an inventive layout of A–B–A–C–B–A, cleverly interwoven and coming close to being palindromic.

Cello Sonata in F major, Opus 6

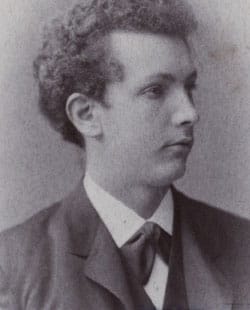

Richard Strauss

Born: June 11, 1864, in Munich

Died: September 8, 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany

Composed: 1881 (rev. 1883)

We meet Richard Strauss at the age of 19, well before he wrote the symphonic poems and operas that keep him before the public today, even two years before he composed the earliest of his lieder that became repertoire chestnuts, “Allerseelen” and “Zueignung.” He had kept busy as a lad; this son of a renowned horn player started piano lessons at four, violin lessons at eight, and composition instruction at 11. He produced much music during those early years, and in 1881 he published his Opus 1, the orchestral Festmarsch.

His cello sonata traces its genealogy to that same year. In December 1880, a music magazine announced a competition for new works for cello and piano in various categories, including sonatas, with the distinguished composers Niels Gade and Carl Reinecke among the judges. Strauss finished the first two movements of his sonata in March, the third in May; he submitted the complete piece; and he didn’t win. In 1886, he recalled this adventure in a letter to his father: “As far as concerns the Cello Sonata in its original state, I am entirely in agreement with the adjudicators of that time. I also would not have given it a prize.” Still, it had been performed publicly before the competition ended, played by Hanuš Wihan, principal cellist of the Munich Court Orchestra, and Joseph Giehrl, to whom Strauss had recently dedicated his Piano Sonata, Opus 5. It earned the audience’s enthusiasm, but Strauss set the piece aside nonetheless. He picked it up again sometime later, probably in the autumn of 1882, and by the time he finished with it, in the first half of 1883, he had effected drastic changes in the first movement and replaced the other two entirely. It was promptly released by a publisher, to a lukewarm reception in the press. “In general,” one critic stated, “the musical training of the young composer seems by no means to have been concluded; on the whole, it speaks more for great natural ability and fresh melodic talent than proficiency in the art of composition.” That must have stung; but the piece—in its rewritten form—was more warmly reviewed when it received its first performance, in December 1883, again with Wihan, now with pianist Hildegard von Königsthal.

Then things got messy. Wihan was a superb cellist, the future dedicatee of Dvořák’s Cello Concerto, though he did not get to premiere it. But Strauss apparently struck up a dalliance with Wihan’s wife, Dora, and their marriage ended soon after that. Before long, Strauss began touring the piece with other cellists, and the work’s reputation was increasingly secured. “Well, my Sonata was extraordinarily well received,” the composer wrote to his mother after a performance in Dresden, with cellist Ferdinand Böckmann. “It was tremendously applauded. I was congratulated on all sides, and everyone was of one mind about it all. Böckmann played it very beautifully.”

As his fame spread, Strauss would get labeled as a musical descendent of Richard Wagner, but in this piece we spy more of a Mendelssohnian buoyancy, along with a lyrical dash of Schumann. The first movement unrolls comfortably in its clearly structured sonata form (the indication of grazioso is well met near the end of the exposition), breaking into a fugal passage (sempre grazioso) near the movement’s end. The second movement is a beautiful expanse, pensive at the outset, in strikingly Schumannesque “fantasy” style. There is no scherzo, which in many four-movement sonatas of the time would have come next. Nonetheless, Strauss’s finale incorporates a good deal of scherzo-ish flavor, all the more prescient for listeners acquainted with his tone poem Till Eulenspiegel, which would appear slightly more than a decade later, in 1894–95; one senses it waiting in the wings.

Piano Trio in G minor, Opus 15

Bedřich Smetana

Born: March 2, 1824, in Leitomischl, Bohemia

Died: May 12, 1884, in Prague

Composed: 1855

Bedřich Smetana, whose bicentennial we celebrate this year, was a great figure of Czech nationalism, the composer of numerous operas (of which The Bartered Bride surfaces most regularly), and, most famously, of the group of six symphonic poems known as Má Vlast (My Fatherland) and especially the second item in that set, Vltava (The Moldau), which has achieved the status of unofficial musical ambassador from the Czech Lands. These tend to steal the scene from his other works, many of which are remarkable.

The G-minor piano trio, his first great composition, was born of a tragic event. In 1849 he had married Kateřina Kolářová, and they became the parents of four daughters in quick succession. The second daughter, Gabriela, died in June 1854, and in September 1855 the eldest, Bedřiška (her father’s namesake, affectionately called Fritzi) perished of scarlet fever. The fourth daughter was born less than two weeks before Bedřiška died; she would die the following year. Of the four, only the third would live a full life. What’s more, Smetana’s wife was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1855; she would live only until 1859. Smetana had particularly adored Bedřiška thanks to her incipient signs of musical aptitude. “Nothing can replace Fritzi,” he wrote in his diary, “the angel whom death has stolen from us.” He immediately embarked on the composition of his G-minor Piano Trio, which he dedicated “in memory of our eldest child Bedřiška, whose rare musical talent gave us such delight; too early snatched from us by death at the age of 4½ years.”

There is no mistaking the serious mien of this trio. All three of its movements are in the key of G minor, and those sections that unroll in the major mode do so out of the necessities of musical contrast without really doing much to lighten the somber mood. Falling intervals predominate in the themes—the sounds of weeping or at least sighs. Such a sinking theme is cried out, espressivo, right at the opening by the violin, against which the cello soon intones a yearning theme in beautifully crafted counterpoint. Although the composer never revealed an explicit program through which this piece could be construed as a portrait of his departed daughter, he did once maintain that the second theme of the first movement alludes to a tune that Bedřiška particularly loved. A brief solo passage for piano in the middle of the movement sounds strikingly Chopinesque, testifying to Smetana-the-pianist’s early infatuation with that composer’s music.

Smetana stays in the tonic key of G minor for the second movement, which is laid out as a scherzo with two trios. If Chopin had seemed a kindred soul in the first movement, Robert Schumann would appear to have inspired the second—or perhaps Mendelssohn in the scurrying of the opening section.

The finale opens with bustling rhythms, the strings energizing the texture further through occasional plucks of pizzicato. A reflective theme is introduced by the cello and then answered immediately by the other instruments (the piano embellishing it with Chopinesque figuration). Near the end, Smetana inserts a funereal section, a slow march that the piano punctuates with what we may hear to be the tolling of bells.

Despite the obvious emotion behind the piece and the skill Smetana displayed in working out his material, the piece was received coolly by critics at its premiere, in December 1855, when it shared the bill with Schubert’s string quintet and Schumann’s piano quintet. Only when Liszt extolled the work, after hearing it at the Smetanas’ home during a visit to Prague the following year, did the piece’s fortunes change. Smetana returned to his score and effected a number of revisions. He retouched it further prior to publication in 1879, and it is in this ultimate version that the work went on to become the repertoire staple it is, and deserves to be, today.

—James M. Keller

James M. Keller, now in his 24th season as Program Annotator of the San Francisco Symphony, is the author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s Guide (Oxford University Press) and is writing a sequel volume about piano music.

About the Artists

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Mr. Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Mr. Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Mr. Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Mr. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Mr. Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri “del Gesu”̀ violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Mr. Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Mr. Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick joined the San Francisco Symphony in 1999, served as Associate Principal Cello through the 2022–23 season, and now holds the Lyman & Carol Casey Second Century Chair. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Mr. Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Mr. Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.

Extended Reading