In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, November 24, 2024, at 2:00pm

Radu Paponiu conducting

Wattis Foundation Music Director

San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra

Leonard Bernstein

Overture to Candide (1956)

Takashi Yoshimatsu

Cyber Bird Concerto, Opus 59 (1994)

Bird in Colors

Bird in Grief

Bird in the Wind

Harry Jo alto saxophone

Intermission

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36 (1878)

Andante sostenuto–Moderato con anima, in movimento di valse

Andantino in modo di canzona

Scherzo, pizzicato ostinato: Allegro

Finale: Allegro con fuoco

The Youth Orchestra concerts are supported by

Program Notes

Overture to Candide

Leonard Bernstein

Born: August 25, 1918, in Lawrence, Massachusetts

Died: October 14, 1990, in New York

Work Composed: 1956 (arr. 1957)

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbal, snare drum, tenor drum, bass drum, glockenspiel, and xylophone), harp, and strings

Duration: About 5 minutes

Chic celebrity he may have been, Leonard Bernstein was something of a throwback to an earlier age when to be a musician meant to encompass the whole of the art rather than to segregate oneself into a well-defined specialty. Bernstein could do everything, and he could do it all well: composer, conductor, pianist, teacher, writer.

Candide was a product of Bernstein’s Broadway years. Based on Voltaire’s 1759 satire concerning the misadventures of the guileless naïf Candide and his sweetheart Cunégonde, the show was only a modest success during its original 1956 run, probably due to its perceived intellectualism. Later revivals, most with a book by Hugh Wheeler in the place of Lillian Hellman’s original, have been more successful. However, those revivals have added, subtracted, reshuffled, and restructured the piece as later librettists—Stephen Sondheim, John Mauceri, John Wells, Richard Wilbur, even Bernstein himself—have come and gone, each leaving his or her mark. There can be no “definitive” version of Candide.

Bernstein provides a scintillating Overture that crackles with the rhythms of the mid-18th century, busy and almost frenetic, a kissing cousin to that dazzling tour de force that kicks off Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. Unlike the Mozart, however, Bernstein’s score incorporates tunes from the show proper: “The Best of All Possible Worlds,” “Battle Music,” “Oh, Happy We,” and perhaps most memorably, the soprano throat-scorcher “Glitter and Be Gay.”

In its beefed-up 1957 version for full symphony orchestra, the Overture quickly took its place as Bernstein’s most frequently performed work. It can be heard in its theatrical scoring in the original cast recording, but it’s Bernstein’s own recordings—1960 with the New York Philharmonic and 1983 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic—that are most familiar. In 1989, one year before his death at age 72, Bernstein gave Candide a thoroughgoing overhaul. Happily, this version was captured in a splendid full-length recording, preserving this iconic American musician’s last thoughts on his beloved, polymorphic problem child.

—Scott Foglesong

Cyber Bird Concerto, Opus 59

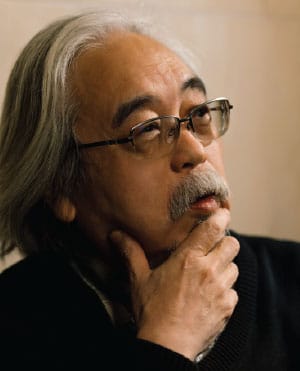

Takashi Yoshimatsu

Born: 1953, in Tokyo

Work Composed: 1993–94

Instrumentation: solo alto saxopohone, piccolo, 2 flutes

(2nd doubling alto flute), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 horns,

3 trumpets, 3 trombones, percussion, piano, and strings

Duration: About 23 minutes

Takashi Yoshimatsu is a Japanese composer who came to music through jazz and rock and now embraces a lyrical style. His first major work, Threnody to Toki, debuted in 1981, and he has since written six symphonies and 10 concertos, among other orchestral and chamber works for both Japanese and European instruments. His works are recorded by Chandos Records, where he was appointed composer in residence in 1998. He has also written for film and television, including the score for the 2003 series Astro Boy.

Yoshimatsu wrote the Cyber Bird Concerto between 1993–94 for the saxophonist Nobuya Sugawa, and it also features prominent parts for piano and percussion. The composer recalled writing the slow movement, an elegy, in a hospital where his sister was dying from a terminal illness: “the last thing she said before she died was ‘I would like to be a bird in my next life.’ This composition is stamped with the name of her soul.” In his liner notes for the Chandos recording of the concerto, Yoshimatsu further describes:

The saxophone belongs both to the realms of modern classical music and 20th-century jazz. It is also a very popular instrument that permeates the scene in present-day Japan, appearing in such varying settings as rock bands and chindonya (Japanese downtown street bands). Its music therefore naturally bears the essences of 20th-century “artistic music” and “entertainment music.” It may therefore be the most suitable instrument for surveying our era.

Cyber Bird indicates an imaginary bird in the realm of electronic cyberspace. It consists of three movements, fast–slow–fast, in which the saxophone, borne by the orchestra’s wings, takes flight within this imaginary space, flying through a variety of classical, jazz, rock, and ethnic scenes to reach its own stratum.

I. Bird in Colors: A somewhat frenzied Allegro in which a bird flies through strata of varying colors.

II. Bird in Grief: An Andante in which a bird’s soliloquy of sadness is paralleled by birdsong that spins out a dream.

III. Bird in the Wind: A Presto in which a bird flies straight on, into the wind.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36

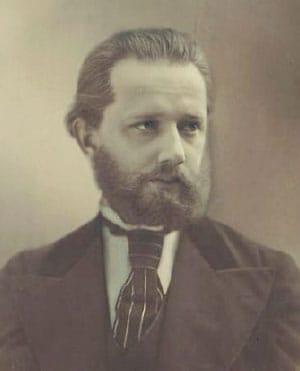

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg

Work Composed: 1878

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 45 minutes

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony starts with a clashing fanfare—an idea the composer connected with the famous opening of Beethoven’s Fifth, widely understood to represent fate. But their conceptions of fate are wildly different: For Beethoven, the shock of the opening idea, the knock at the door, generates the rest of the movement and propels the entire symphony. But for Tchaikovsky, fate is not a creative force, instead it’s an intrusion that thwarts peace and shatters beauty.

He wrote as much to Nadezhda von Meck, his patron and confidante, and the secret dedicatee of the Fourth Symphony:

This is Fate, the force of destiny, which ever prevents our pursuit of happiness from reaching its goal, which jealously stands watch lest our peace and well-being be full and cloudless, which hangs like the sword of Damocles over our heads and constantly, ceaselessly poisons our souls.

He goes on, providing her with a description of the entire piece in similar terms. Whether this program guided his composition from inception, or whether it was an after-the-fact translation of music into words for the benefit of a patron, is debatable.

But Tchaikovsky certainly had reason to think of fate in such a way, especially as 1877 marked a major crisis in his life. He had just left his new wife, Antonina Milyukova, whom he had married earlier that same year. Tchaikovsky, who is generally understood to have been gay, thought they were entering a marriage of convenience—she, apparently, didn’t know or understand this. He was still recuperating from the ordeal of their separation when he wrote most of the Fourth Symphony.

We can also look at the symphony through an aesthetic and political lens: Though Tchaikovsky drew a comparison to Beethoven, he wasn’t fully an admirer, and was even less an admirer of Johannes Brahms, who was seen as Beethoven’s heir and the leading symphonist of the day. Tchaikovsky criticized what he heard as overly analytical, tightly-constructed Germanic music. But at the same time, he stood apart from his fellow Russian composers as more educated, more professional, and more Western.

Most of his compatriots were musically self-educated and held day jobs (Alexander Borodin notably as a chemist, others as civil servants and military officers). Even Tchaikovsky initially worked as a civil servant for three years before the Saint Petersburg Conservatory opened its doors in 1862. It was the first place a Russian could receive a formal music education, taught in Russian, without leaving the country. Tchaikovsky enrolled and graduated with the first class.

In the following years, he struggled with the symphonic form, trying to avoid the self-consciously exotic “Eastern-ness” that brought Mikhail Glinka and Borodin both cachet and derision in Western Europe, while also trying to downplay the nuts-and-bolts craftsmanship his conservatory teachers had obsessed over.

The Fourth Symphony is a stunning realization of this middle path. Tchaikovsky found he could place unrelated musical ideas next to each other and let the latent drama of their juxtapositions emerge. It’s a technique that also served him well in opera and ballet, where music delineates characters as they interact and come into conflict.

In the symphony, nothing is quite so literal: Heroes and fairytale characters are stripped down to anonymous musical ideas, then cast into four movements which roughly hit the expected markers of the symphonic form. But what unfolds in-between is wholly original and unexpected.

The Music

After the fateful fanfare recedes, the main theme is a waltz—an unusual choice for the first movement of a symphony. From there comes a succession of escapist melodies, which Tchaikovsky called “sweet tender dreams.” But fate is never far away, returning violently three more times, shattering any illusion of peace.

The slow movement, Andantino in modo di canzona (in the manner of a song), has a mournful theme, first presented in the oboe, then cellos, then elaborated upon, and finally ending with the bassoon.

The Scherzo explodes the orchestra into its constituent factions. First, the plucked strings scurry along. Then, the strings drop out and the woodwinds play a rustic tune. Next comes the brass (with some clarinet and piccolo for color), and then the plucked strings return. While traditional orchestration focused on blending and subtle layering, Tchaikovsky found bold effects in the opposite approach.

The finale begins from a point of triumph, then descends back into tumult. It is no surprise that fate makes a return, and the result—whether transcendent or cataclysmic—is something listeners might ponder. Tchaikovsky, in a nod to his more nationalistic colleagues, quotes a Russian folksong, which could provide a subtext: “I will take a walk in the forest, I will cut down the birch tree, Lyu-li, lyu-li, I’ll cut it down.” But from that tree, the singer makes a balalaika.

—B.P.

A version of the Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4 note previously appeared in the program book of the St. Louis Symphony.

About the Artists

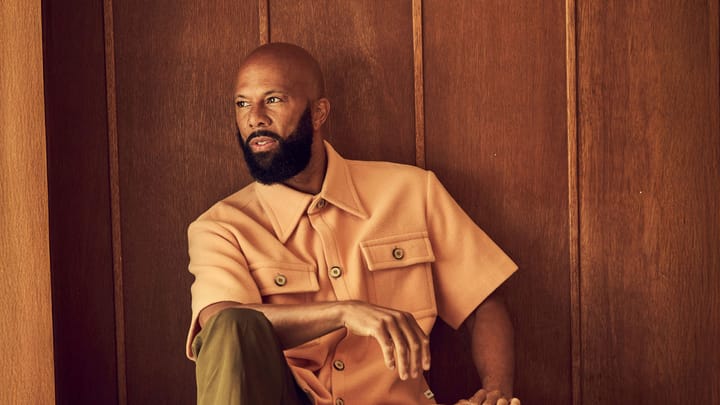

Radu Paponiu

Radu Paponiu was appointed Wattis Foundation Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra at the beginning of this season. He recently completed a five-year tenure as associate conductor of the Naples (Florida) Philharmonic and a seven-year tenure as music director of the Naples Philharmonic Youth Orchestra. He has also served as music director of the Southwest Florida Symphony, assistant conductor of the Naples Philharmonic, and as a member of the conducting faculty of the Juilliard Pre-College.

As a guest conductor, Paponiu has appeared with the Romanian National Radio Symphony, Teatro Comunale di Bologna Orchestra, Transylvania State Philharmonic, Banatul Philharmonic, Louisiana Philharmonic, Rockford Symphony, Colorado Music Festival Orchestra, North Carolina Symphony, California Young Artists Symphony, and National Repertory Orchestra. He has collaborated with soloists such as Evgeny Kissin, Yefim Bronfman, Emanuel Ax, Gil Shaham, Midori, Vladimir Feltsman, Robert Levin, Charles Yang, Nancy Zhou, Stella Chen, and the Ébène Quartet.

Born in Romania, Paponiu began his musical studies on the violin at age seven, came to the United States at the invitation of the Perlman Music Program, and later completed two degrees in violin performance at the Colburn School. He went on to earn a master’s degree in orchestral conducting at New England Conservatory, where he studied with Hugh Wolff.

Harry Jo

Harry Jo, the winner of the 2023–24 San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra Concerto Competition, is a first violinist in the orchestra and a senior at Amador Valley High School. He began his musical journey at age five on the piano, took up violin at eight, and finally alto saxophone at 11. He joined the SFJazz High School All-Stars Band in 2022, where he is currently lead alto saxophone and a member of the combo ensemble. He recently toured with the award-winning group to New Orleans and New York.

On saxophone, Jo has performed on NPR’s From the Top and was recognized as a 2023 National YoungArts Winner in Jazz. He is also the winner of a 2023–24 Jazz at the Ballroom Scholarship Award and a 2024 Creative Youth Awards Presidential Award. In 2020 and 2021, he was a member of the Junior High Jazz Band at the California All-State Music Education Conference and received the Scholarship Award at the Campana Jazz Festival in 2020 and 2023. He has won many awards on all three of his instruments, and as the winner of the American Protégé Music Competition, he performed on violin at Carnegie Hall.

San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra

First Violins

Ian Cheung, Co-Concertmaster

Euisun Hong, Co-Concertmaster

Madison Lin, Co-Concertmaster

Xinyan Shi, Co-Concertmaster

Lawrence V. Metcalf Chair

Thais Chernyavsky

Connor Chin

Hyesun Hong

Isaiah Iny-Woods

Ella Jeon

Harry Jo

Spencer Kogoma

Andre Lu

Aaron Ma

Henry Miller

Lisa Saito

Jenna Son

Luke Spivey

Joy Wang

Second Violins

Valery Breshears, Co-Principal

Sydney Li-Jenkins, Co-Principal

Asher Cupp

Udo Funke

Christina Hong

Maximilian Huang

Kayla Hwang

Constance Kuan

William Liang

Veronica Qiu

Carolyn Ren

Yujin Shin

Henry Stroud

Kate Vo

Lucy Wang

Junnosuke Yanagisawa

Katherine Yoo

Andrew Zhang

Violas

Andrew Hwang, Co-Principal

Bryan Im, Co-Principal

Rebekah Sung, Co-Principal

Harper Berry

Jamie Cheung

Timothy Cheung

Ethan Han

Jaydon Li

Haoching Liu

Charlotte Elise Lopez

Olivia Park

Yufei Shen

Kenji Sor

Nicole Targosz

Katherine Yang

Cellos

Huisun Hong, Principal

Starla Breshears

Irei Fromme

Gabriel Irazabal

Benjamin Jiang

Melissa Lam

Claire Law

Kenneth Ma

Seoyeon Moon

Claire Topper

Keiya Wada

Cara Wang

Basses

Raiden Tan, Principal

Joshua Ahn

Shreyas Anand

Alec Blair

Youmy Gonzalez

Haku Homma

Vera Kolodko

Jackson Pascual

Allison Prakalapakorn

Flutes

Sophia Bian

Diego Fernandez

Cadence Liu

Yuzuka Williams

Oboes

Gabriel Chodos

Nicholas Karr

Jesse Spain

Valerie Xu

Clarinets

Ryan Beiter

Subin Kim

Hanting Liu

Adam Thyr

Bassoons

Adam Erlebacher

Zach Noble

Chelsea Park

Aya Watanabe

Horns

Thomas Chang

Violet MacAvoy

Samay Sayala

Owen Sheridan

Nicholas Taylor

Trumpets

Kanon Homma

Jordan Ku

Logan Manildi

Mason Rogers

Trombones

Mason Chambers

Thomas Valle

Tuba

Sean Taburaza

Timpani & Percussion

Leo Chun

Gabriela Garcia

Jeffrey Lee

Matthew Pizzi

Naoto Watanabe

Alexander Xie

Harp

Jessica Cheung

Camille Chu

Keyboard

Dylan Hall

Radu Paponiu,

Wattis Foundation Music Director

Coaching Faculty

David Chernyavsky, violin

In Sun Jang, violin

Chen Zhao, violin

Adam Smyla, viola

Jill Brindel, cello

David Goldblatt, cello

Stephen Tramontozzi, bass

Catherine Payne, flute

Russ de Luna, oboe

Matthew Griffith, clarinet

Jerome Simas, clarinet

Justin Cummings, bassoon

Jesse Clevenger, horn

Jeff Biancalana, trumpet

Christopher Bassett, trombone & tuba

Jacob Nissly, percussion & timpani

Marty Thenell, percussion & timpani

Katherine Siochi, harp

Marc Shapiro, keyboard

Youth Orchestra Administration

Ron Gallman, Director of Education and Youth Orchestra

Daniel Hallett, Associate Director, Youth Orchestra Program

Katie Lee, Youth Orchestra Administrative Apprentice

Charlotte Elise Lopez, Youth Orchestra Library Apprentice

Lily Wang, Youth Orchestra Library Apprentice