In This Program

The Concert

Wednesday, February 19, 2025, at 7:30pm

Tessa Lark violin

Jeremy Denk piano

Béla Bartók

(arr. Zoltán Székely)

Romanian Folk Dances (1915)

Joc cu bâtă (Stick Dance, Allegro moderato)

Brâul (Sash Dance, Allegro)

Pe loc (In One Spot, Andante)

Buciumeana (Horn Dance, Molto moderato)

Poargă Românească (Romanian Polka, Allegro)

Mărunțelul (Fast Dance, Allegro—Più allegro)

Eugène Ysaÿe

Sonata No. 4 in E minor for Solo Violin, Opus 27, no.4 (1923)

Allemande

Sarabande

Finale

Tessa Lark

Ysaÿe Shuffle (2023)

Jig and Pop (2023)

Fritz Kreisler

Chanson Louis XIII and Pavane in the style of Louis Couperin (1910)

Syncopation (1924)

John Corigliano

Sonata for Violin and Piano (1963)

Allegro

Andantino

Lento

Allegro

This concert is performed without intermission.

Program Notes

Romanian Folk Dances

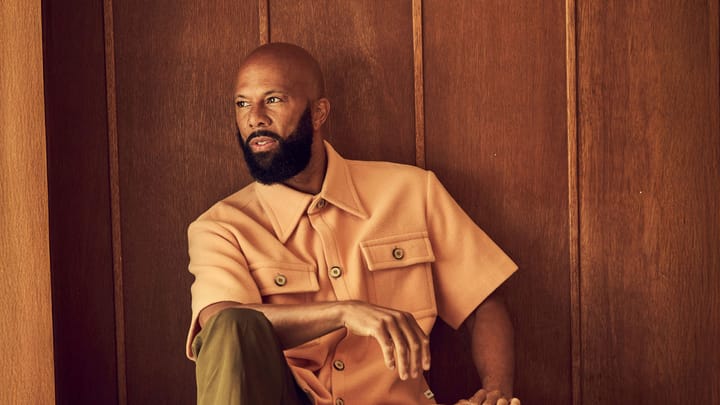

Béla Bartók

Born: March 25, 1881, in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary

Died: September 26, 1945, in New York

Work Composed: 1915 (arr. 1925)

As a recent graduate of the Budapest Academy of Music, Béla Bartók grew fascinated by the folk music of his homeland, a region where national borders shifted depending on political developments. While spending six months of 1904 in the resort village of Gerlice Puszta in northern Hungary (now Ratkó, Slovakia), he became entranced by the songs he overheard being sung by a Transylvanian housekeeper. He notated some of her songs, and several months later, in December 1904, wrote to his sister, “Now I have a new plan: to collect the finest Hungarian folksongs and to raise them, adding the best possible piano accompaniment, to the level of art-song.”

Within a couple of months he published his first such effort, a group of Transylvanian and Hungarian pieces, and after that there was no turning back. By 1906 he began to collect Slovak folk music, and two years later plunged into the repertoire of Romania. Later research trips would bring him into direct contact with folk music of Ruthenia, Serbia, Croatia, Bulgaria, and places as far away as Turkey and North Africa.

Beginning in 1909, he was assisted by his Romanian friend Ion Bușiția in the logistics of planning these trips, and it is to Bușiția that Bartók accordingly dedicated his Romanian Folk Songs, composed in 1915 as piano solos. These are pieces of the sort he described in his letter to his sister—intact melodies accompanied by original harmonizations. One of his most popular and frequently performed works, Romanian Folk Dances is also heard in various arrangements, most notably this arrangement by violinist Zoltán Székely, who performed the set often with the composer. Bartók initially titled this suite Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary, reflecting the fact that when he collected the pieces in Transylvania, that region was within Hungarian borders. After the Treaty of Trianon redrew the map, he renamed the set simply Romanian Folk Dances. Its short movements are to be played without a break. Apart from the concluding two-section dance, each movement uses a melody from a different region of Transylvania, and together they display quite an array of melodic-harmonic modes—Dorian, Lydian, Mixolydian, and Aeolian, as well as more exotic modes of possibly Arabic descent.

Sonata No. 4 in E minor for Solo Violin, Opus 27, no.4

Eugène Ysaÿe

Born: July 16, 1858, in Liège, Belgium

Died: May 12, 1931, in Brussels

Work Composed: July 1923

Eugène Ysaÿe’s surname can look scary to non-French-speakers, so all together now: “ee-zah-EE.” A pupil of violin superstars Henryk Wieniawski and Henri Vieuxtemps, he grew close to many of the most important French and Belgian composers of his time, premiering the violin sonatas of César Franck and Guillaume Lekeu as well as Ernest Chausson’s Concert and Poème. More than 50 compositions carry dedications to him, including string quartets by Claude Debussy, Vincent d’Indy, and Camille Saint-Saëns, and Gabriel Fauré’s Piano Quintet No. 1. From 1879–82 he was concertmaster of the orchestra that evolved into the Berlin Philharmonic. From there he proceeded to an international career as a recital soloist and kingpin of chamber music. He first toured the United States in 1894 and 1895, and further visits took him all the way to California. Stranded in the United States during World War I, he accepted the music directorship of the Cincinnati Symphony, a post he held from 1918 to 1922, serving Ohioans with much music by his circle of French colleagues. Upon returning to Belgium, he resumed his busy schedule as a recitalist and chamber player, and he continued composing until his death.

His most frequently played compositions are his Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, Opus 27, large-scale, technically challenging works written in a surge of creativity in July 1923, reportedly inspired by hearing a recital in which Joseph Szigeti performed Bach scores for unaccompanied violin. Each of the six is dedicated to a notable violinist of that time and is crafted to reflect something about each one’s musical personality: Szigeti, Jacques Thibaud, George Enescu, Fritz Kreisler, Mathieu Crickboom, and Manuel Quiroga. The Fourth Sonata is a tribute to Kreisler, who back in 1911 had dedicated to Ysaÿe his own Recitativo et Scherzo-Caprice, Opus 6, for unaccompanied violin. Sonata No. 4 plays off a characteristic we shall encounter shortly in this concert: Kreisler’s penchant for composing original pieces in antique style. Ysaÿe casts his first two movements as dance-pieces of the sort typical in Baroque suites. The first is an Allemanda in which a four-note figure runs throughout as a sort of ostinato. There follows a Sarabande in which the violin plays in three-voiced counterpoint, in pizzicato at the beginning and end, bowed in the central section. The finale is mostly a moto perpetuo that scurries along in 5/4 meter.

Ysaÿe Shuffle and

Jig and Pop

Tessa Lark

Born: June 8, 1989, in Richmond, Kentucky

Works Composed: 2023

Tessa Lark started using the term “Stradgrass” in 2015 to designate the body of work she was creating—concert music inspired by bluegrass, which she played on her Stradivarius violin. Her classical-music bona fides were beyond reproach; by then she had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from New England Conservatory and was playing that particular Strad because it was loaned to her after she took second place at the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis in 2014. But bluegrass was also an organic component of her musical self; she heard it all the time while growing up in Kentucky, where her father played gospel-bluegrass music on banjo and her mother was a pianist.

She included some of these pieces on her 2023 recording The Stradgrass Sessions, which she described as “a snapshot of the way I live in music: diversely, organically, intimately, sometimes collaboratively, sometimes solitarily, always sincerely.”

She continued:

Jig and Pop was inspired by a fiddle-sounding motif that composer/bassist Michael Thurber asked me to play and improvise on for one of his pop songs. The bustling optimism immediately sparked more ideas for this piece, a virtuosic moto perpetuo inspired by the feel of an Irish fiddle master playing a simple tune over and over but ever new and entrancing each time.

Ysaÿe Shuffle is a quick musical double-entendre, shuffling motives and form from the Finale of Ysaÿe’s Sonata No. 4, and amply employing what’s known in fiddle culture as a “shuffle” bowing. It was written for Carolyn Lowenthal as a result of her generosity toward the Irving M. Klein International Strings Competition; Carolyn is a violinist in her spare time, and I wrote this as a sort of etude to introduce her to fun fiddling techniques like the “chop,” various double-stopping, and, of course, the “shuffle.”

Chanson Louis XIII and Pavane in the style of Louis Couperin

and Syncopation

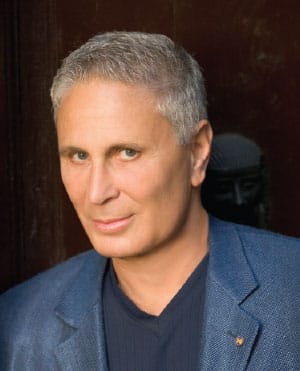

Fritz Kreisler

Born: February 2, 1875, in Vienna

Died: January 29, 1962, in New York

Works Composed: Chanson Louis XIII and Pavane—ca. 1910. Syncopation—ca. 1924

Fritz Kreisler was among the greatest of the great violinists: a legend in his own time and a fiddler for the ages. His destiny seemed clear practically from the outset, when at the age of seven he became the youngest student ever admitted to the Vienna Conservatory. He graduated with a gold medal and moved on to the Paris Conservatory, which awarded him a premier prix when he was 12, and that was the last violin instruction he ever had. Throughout his career, he performed with a unique combination of ease, grace, charm, technical perfection, tonal luster, and idiosyncratic personality.

He also composed quite a few works, including a string quartet, and he gained notoriety for attributing some of his pieces written “in the antique style” to long-gone composers whose names were vaguely familiar to music lovers but whose music was utterly forgotten. A notice at the head of the published editions stated that the pieces were “so freely treated that they constitute, in fact, original works” and that “when played in public, Mr. Kreisler’s name must be mentioned on the programme.” So it is that pieces ostensibly by Pugnani, Tartini, Dittersdorf, Francoeur, and the like turned out to be hoaxes by Kreisler, as he revealed in 1935 to the chagrin of more than a few musicologists and critics who had applauded his antiquarian initiative.

Chanson Louis XIII and Pavane in the style of Louis Couperin refers to Louis Couperin (1626–61), a notable French Baroque harpsichordist and organist, uncle of the more famous François Couperin (also a harpsichordist and organist). Today, many revere Louis Couperin’s intimate, dark-hued compositions, but when Kreisler invoked his name in 1910, almost nobody would have been the wiser about this stately Chanson or the sparkling Pavane that follows it without a break—or even that a pavane should have been more solemn than the allegretto Kreisler’s score suggests.

Syncopation reflects the 1920s vogue for classical-jazz crossover. Dating Kreisler’s compositions is fraught with uncertainty. This ragtime-infused morsel was published in 1925 as a piece for violin and piano and in 1926 for piano trio, but he had already recorded the trio version in 1924, when he was joined by his brother Hugo on cello and pianist Charlton Keith.

Sonata for Violin and Piano

John Corigliano

Born: February 16, 1938, in New York

Work Composed: 1962–63

John Corigliano heard lots of violin playing as he grew up, since his father was for 23 years the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic. In fact, the score for his Violin Sonata carries the notation “Violin part edited and fingered by John Corigliano, Sr.” Following an early period when his music (he said) was a “tense, histrionic outgrowth of the ‘clean’ American sound of Barber, Copland, Harris, and Schuman,” he embraced a posture in which Romantic grandeur can rub elbows with a modernist musical vocabulary, always aiming to connect with the audience. One does not turn to Corigliano with expectations of a predictable style. “I feel very strongly that a composer has a right to do anything he feels is appropriate,” he said, “and that stylistic consistency is not what makes a piece impressive.” What he does value in a composition is its ability to convey musical and emotional content in a way that involved listeners can grasp. “I wish to be understood,” Corigliano says, “and I think it is the job of every composer to reach out to his audience with all the means at his disposal. Communication should always be a primary goal.”

His career has been filled with distinctions. In 1991, his Symphony No. 1 earned the Grawemeyer Award and a Grammy for Best Contemporary Composition. In 1992, Musical America named him its first Composer of the Year. His score for The Red Violin won an Academy Award in 2000 and he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music in 2001 for his Symphony No. 2. In his own program note, he said:

The Sonata for Violin and Piano, written during 1962–63, is for the most part a tonal work. although it incorporates non-tonal and poly-tonal sections within it as well as other 20th-century harmonic, rhythmic, and constructional techniques. The listener will recognize the work as a product of an American writer, although this is more the result of an American writing music than writing “American” music—a second-nature, unconscious action on the composer’s part. Rhythmically, the work is extremely varied. Meters change in almost every measure, and independent rhythmic patterns in each instrument are common. The Violin Sonata was originally entitled Duo, and therefore obviously treats both instruments as co-partners. Virtuosity is of great importance in adding color and energy to the work which is basically an optimistic statement, but the virtuosity is always motivated by musical means.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Tessa Lark

Tessa Lark was nominated for a 2020 Grammy Award for Best Classical Instrumental Solo, and is also a highly acclaimed fiddler in the tradition of her native Kentucky. This season she returns to the BBC Symphony and Rochester Philharmonic, and debuts with Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. As a chamber musician, she recently toured with bassist Edgar Meyer and cellist Joshua Roman to Cal Performances and the Boston Celebrity Series.

Lark has appeared with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony, Louisville Orchestra, Knoxville Symphony, and Indianapolis Symphony, and has performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Wigmore Hall, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, San Francisco Performances, and numerous summer festivals. Her most recent album, The Stradgrass Sessions, features an all-star roster of collaborators and composers including Edgar Meyer, pianist Jon Batiste, mandolinist Sierra Hull, and fiddler Michael Cleveland. Her debut recording was the Grammy-nominated SKY, a bluegrass-inspired violin concerto written for her by Michael Torke and performed with the Albany Symphony.

Lark is a recipient of the Hunt Family Award, one of Lincoln Center’s prestigious Emerging Artist Awards, as well as a 2018 Borletti-Buitoni Trust Fellowship and a 2016 Avery Fisher Career Grant. She was Silver Medalist in the 9th Quadrennial International Violin Competition of Indianapolis and winner of the 2012 Naumburg International Violin Competition.

Lark is a graduate of New England Conservatory and completed her artist diploma at the Juilliard School. She currently plays a ca. 1600 G.P. Maggini violin on loan from an anonymous donor through the Stradivari Society of Chicago. She makes her debut at the San Francisco Symphony with this recital. Read our interview with Lark.

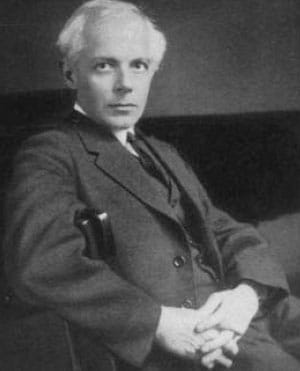

Jeremy Denk

Jeremy Denk is one of America’s foremost pianists. Also a New York Times bestselling author, he is the recipient of both the MacArthur Fellowship and the Avery Fisher Prize, and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In the 2024–25 season, Denk continues his collaboration with longtime musical partners Joshua Bell and Steven Isserlis, with performances at the Tsindali Festival and Wigmore Hall, following on from his multi-concert artist residency at Wigmore in 2023–24. He also returns to the Lammermuir Festival in multiple performances, including the complete Ives violin sonatas with Maria Wloszczowska, and a solo recital featuring female composers from the past to the present day. He performs this same solo program on tour across the US, as well as continuing his exploration of Bach in ongoing performances of the complete partitas. Denk is known for his interpretations of the music of American visionary Charles Ives, and in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth, Nonesuch Records will release a collection of his Ives recordings later this year.

Denk is also known for his original and insightful writing on music. His New York Times bestselling memoir, Every Good Boy Does Fine was published to universal acclaim by Random House in 2022. He also wrote the libretto for a comic opera presented by Carnegie Hall, Cal Performances, and the Aspen Festival, and his writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the New Republic, the Guardian, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and on the front page of the New York Times Book Review.

Denk’s latest album of Mozart piano concertos was released in 2021 on Nonesuch Records. His recording of the Goldberg Variations for Nonesuch Records reached No. 1 on the Billboard Classical Charts, and his recording of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Opus 111 paired with Ligeti’s Études was named one of the best discs of the year by the New Yorker, NPR, and the Washington Post. His account of the Beethoven sonata was selected by BBC Radio 3’s Building a Library as the best available version recorded on modern piano. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 2006.