In This Program

The Concert

Friday, October 25, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, October 26, 2024, at 7:30pm

Thomas Wilkins conducting

Leonard Bernstein

(arr. Charlie Harmon)

Suite from Candide (1956/98)

You Were Dead You Know–Paris Waltz–

Bon Voyage–Drowning Music/The King’s Barcarolle–

Ballad of Eldorado–I Am Easily Assimilated–

The Best of All Possible Worlds–Make Our Garden Grow

George Gershwin

(orch. Ferde Grofé)

Rhapsody in Blue (1924/26)

Michelle Cann piano

Intermission

William Grant Still

Wood Notes (1947)

Singing River: Moderately slow

Autumn Night: Lightly

Moon Dusk: Slowly and expressively

Whippoorwill’s Shoes: Humorously

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

George Gershwin

(arr. Robert Russell Bennett)

Porgy and Bess, A Symphonic Picture (1935/43)

The October 25 concert is presented in partnership with

These concerts are made possible by the Matthew Kelly Family Foundation.

Thomas Wilkins’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

Generous sponsorship is also provided by Andy & Teri Goodman.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Suite from Candide

Leonard Bernstein (arr. Charlie Harmon)

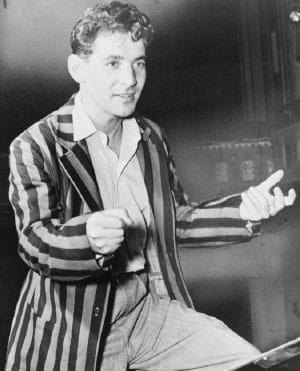

Born: August 25, 1918, in Lawrence, Massachusetts

Died: October 14, 1990, in New York

Work Composed: 1956 (arr. 1998)

SF Symphony Performances: First and only—July 2006. Alastair Willis conducted the Suite. (The SF Symphony has performed other music from Candide numerous times since 1959, including a complete concert performance conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas in January 2018.)

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbals, finger cymbals, tambourine, snare drum, bass drum, temple blocks, wood blocks, and glockenspiel), harp, and strings

Duration: About 17 minutes

Bernstein never talked down to his audience; he talked up what he loved. He believed that concerts offered the experience of collective catharsis, a joyful communion of brain and body. “I feel, love, need, and respect people above all else,” he wrote. “I believe in man’s unconscious, the deep spring from which comes his power to communicate and to love . . . all art’s a combination of these powers.”

Between 1944 and 1961, he was at the peak of his own powers, but his 1956 operetta Candide, his third Broadway show, appeared to be a rare dud. It had a lengthy, costly genesis, and it closed after only 73 performances. According to the critical consensus, playwright Lillian Hellman’s preachy, tone-deaf libretto deserved the blame for Candide’s failure, not Bernstein’s score. The original cast album on Columbia Records sold surprisingly well, keeping the music alive.

Released the year before his hit West Side Story, Candide was an adaptation of Voltaire’s tart parable about a naïve young man and the limits of optimism. The project was conceived by Hellman, who wanted Voltaire’s satire to serve as an indictment of McCarthyism and the House Un-American Activities Committee, which targeted and blacklisted known and suspected communists, including Hellman herself. Bernstein was enthusiastic about the concept, but he wanted the project to be a “comic operetta” rather than a play with incidental music, as Hellman had originally proposed. After she wrote the libretto, a succession of talented freelancers, including James Agee, Richard Wilbur, and Dorothy Parker, contributed song lyrics, not all of which were used. Bernstein and his wife, Felicia, provided lyrics for “I Am Easily Assimilated,” and Bernstein orchestrated the overture himself, repurposing it as a freestanding orchestral work a year later.

Eventually the entire operetta gained more respect, thanks almost entirely to Bernstein’s refusal to accept it as a failure. After a new director and librettist replaced Hellman’s original text, the show was revived in 1973. This time the critics were kinder, the audiences more receptive. Hellman, on the other hand, was so incensed that she withdrew her version from performance.

Bernstein remained passionately committed to the project even in the last year of his life. In 1989, a year before his fatal heart attack, he recorded a new concert version of Candide, explaining, “there’s more of me in that piece than anything else I’ve done.”

The suite, arranged by Charlie Harmon, showcases Candide’s deeper cuts. One such highlight is the irreverent “I Am Easily Assimilated,” in which a comical old mezzo-soprano boasts about being “suddenly Spanish” against Bernstein’s castanets-kissed tango rhythms and spicy syncopation. The fact that “You Were Dead You Know” is a dead-on parody of a frilly bel canto love duet doesn’t make it any less touching. “Paris Waltz” seems to split the difference between Johann Strauss II and Richard Strauss: a rousing, triple-time dance that takes a left turn into art song. Throughout the suite, Bernstein’s rhythmically complex, hyper-tuneful style reveals his eclectic influences, ranging from Argentine tango to African American jazz, as well as traditional European dance forms such as the waltz, mazurka, and gavotte. True to the neoclassical spirit of the project, Bernstein often quotes or imitates other composers, so keep your ears peeled for snippets of Rossini, Gounod, and Gilbert and Sullivan.

Rhapsody in Blue

George Gershwin (orch. Ferde Grofé)

Born: September 26, 1898, in Brooklyn, New York

Died: July 11, 1937, in Hollywood, California

Work Composed: 1924 (rev. 1926)

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1931. Issay Dobrowen conducted with Barnard J. Katz as soloist. Most recent—July 2021. Edwin Outwater conducted the original 1924 version for jazz ensemble with Aaron Diehl as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 alto saxophones, tenor saxophone, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, gong, snare drum, bass drum, and glockenspiel), banjo, and strings

Duration: About 16 minutes

“I’m trying mainly to be American in the feeling of my music,” Gershwin explained in 1936, a year before he fell into a fatal coma caused by a brain tumor. But nailing our national sound was tricky: American culture has always been a hodgepodge of immigrant traditions. Gershwin’s style reflected this reality, a mercurial mixture of jazz, blues, art song, Hebrew laments, Eastern-European hoedowns, and Broadway balladeering. The Great American Songbook was still under construction, not yet named, and Gershwin would be one of its main authors.

His parents, poor Russian Jews, immigrated in the early 1890s. They met and married in New York, first settling in a Jewish neighborhood on the Lower East Side, before moving to Brooklyn. Although George didn’t start playing piano until he was 12, he was earning 15 dollars a week as a songwriter on Tin Pan Alley by his mid-teens. After a few years working as a rehearsal pianist on Broadway, he got a job writing for a music publisher and soon delivered his first big hit, “Swanee,” with lyrics by Irving Caesar. In collaboration with his brother Ira, a gifted lyricist, he churned out a slew of Broadway hits.

When Gershwin wrote Rhapsody in Blue, he was 25 and wildly successful on Broadway, but he still felt like he had something to prove. A decade later, he told a reporter that he “was just trying to express life around me in 1924.” “It was written,” he added, “to put jazz in a more serious form.”

As a native New Yorker who had been listening to jazz all his life, he did more than “make a lady out of jazz,” as the conductor Walter Damrosch stodgily put it. If Rhapsody in Blue is a lady, she’s more streetwise than demure. The opening clarinet glissando, a deliciously sleazy wail, invites us to take a walk on the wild side, far from the purists, scolds, and gatekeepers.

Originally billed as “An Experiment in Modern Music,” Rhapsody in Blue was presented by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, a 22-piece dance band augmented by strings, with Gershwin himself at the piano. Nicknamed the King of Jazz (likely by himself), Whiteman commissioned the piece after enjoying Gershwin’s songs in the recent Broadway flop Blue Monday. Not yet confident as an orchestrator, Gershwin asked Whiteman’s arranger, Ferde Grofé, to flesh it out. Two years after the premiere, Grofé adapted Rhapsody in Blue for full symphony orchestra.

The idea for Rhapsody in Blue came to Gershwin while he was traveling by train to Boston to work on an upcoming musical.

“It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattlety-bang that is often so stimulating to a composer,” he later recalled. “I frequently hear music in the very heart of noise. And there I suddenly heard—and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston, I had a definite plot for the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

Three weeks later, he managed to hit his deadline, although he hadn’t fully transcribed a few passages for solo piano. “I was so pressed for time that I left them to be improvised at the first concert. I could do that as I was to be the pianist.”

Wood Notes

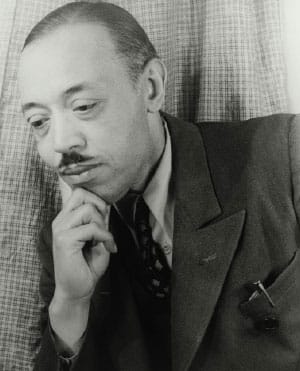

William Grant Still

Born: May 11, 1895, in Woodville, Mississippi

Died: December 3, 1978, in Los Angeles

Work Composed: 1947

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (crash cymbal, suspended cymbal, snare drum, bass drum, and vibraphone), harp, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

William Grant Still completed more than 150 works, including eight operas and five symphonies. He was the first Black American to write a symphony that was performed by a major orchestra, and the first to conduct a major orchestra.

Born in Woodville, Mississippi, Still’s parents were teachers. His father, also the town bandmaster, died when he was three months old. He and his mother moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she remarried. He began taking violin lessons at age 14 and taught himself viola, cello, double bass, clarinet, oboe, and saxophone. In 1911 he enrolled at Wilberforce College, a historically Black university in Ohio, where he would direct the band.

Still received a scholarship to attend Oberlin Conservatory, but his studies were interrupted by a stint in the Navy. After completing his military service, he played as a sideman for bluesman W.C. Handy, who brought him to Memphis and then New York, where he made arrangements for theater orchestras and jazz and blues artists. He also found the time to study independently with the avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse.

Still composed Wood Notes, a pastoral suite for small orchestra, in 1947. The title refers both to a forest and to the woodwind section, arguably the star of this tone poem. He was inspired by the poetry of Joseph Mitchell Pilcher, a social worker who lived in Alabama and wrote about the people and landscape of the American South. In his program notes for the premiere, performed by Artur Rodziński and the Chicago Symphony, Still wrote, “Wood Notes has a social significance because it is a collaboration between a Southern white man and a Southern-born Negro composer, in which both of the participants were enthused over the project.” He dedicated the suite to Friedrich J. Lehmann, his former composition professor at Oberlin.

Singing River, the opening movement and the longest of the four, evokes the richly textured tone painting of Dvořák and Smetana while also honoring Still’s own cultural heritage. Divided strings, bolstered by muted trumpets, simulate the crooning of the titular river. Autumn Night is a teensy tempest, an evening breeze that whips the branches back and forth without terrifying anyone. Marked “slowly and expressively,” Moon Dusk boasts a plangent solo oboe and cinematic strings, which Still juxtaposes and balances to masterful effect. The folk-flavored finale, Whippoorwill’s Shoes, is a rollicking good time, bursting with syncopated dance rhythms, interlocking melodies, and turn-on-a-dime dynamic shifts.

Porgy and Bess, A Symphonic Picture

George Gershwin (arr. Robert Russell Bennett)

Work Composed: 1935 (arr. 1943)

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1943. André Kostelanetz conducted. Most recent—July 2004. Alastair Willis conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, chimes, snare drum, wood block, orchestra bells, and xylophone), 2 harps, banjo, and strings

Duration: About 24 minutes

Porgy and Bess, Gershwin’s self-described “American folk opera,” was a group effort. Although his brother Ira helped out with some of the lyrics, the opera’s librettist, DuBose Heyward, who also wrote the novel on which it was based, supplied most of its best lines. “Summertime,” the opening aria, might be the most recognizable melody in 20th-century musical theater. Pulsing through all three acts, the languorous lullaby is the opera’s lifeblood. Gershwin began writing it in 1933, a full two years before the show’s premiere.

For Porgy and Bess, Gershwin adopted an African American musical vernacular, with a South Carolina accent. Hoping to make the music as authentic sounding as possible, he lived on an island outside of Charleston while composing the score. He and Heyward insisted that all the important roles go to Black performers. The story centered on a tragic love triangle involving Porgy, a disabled pauper with a loving heart; Bess, a desperate abuse victim with a taste for cocaine; and Crown, Bess’s violent dockhand boyfriend, who ditches her after he murders a man and needs to flee. Bess appeals to Porgy for protection, and Porgy kills Crown when he returns for Bess. After being questioned by the police and released, Porgy learns that Bess has left for New York with Sporting Life, a smooth-talking dope dealer. Weary but undaunted, Porgy sets out in his rickety goat cart to find her while singing the spiritual-esque “O Lawd I’m on My Way.”

In 1942, five years after Gershwin’s death, his friend and colleague Robert Russell Bennett arranged a medley for orchestra, at the request of the Pittsburgh Symphony conductor Fritz Reiner. In addition to “Summertime,” Bennett incorporated “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” Sporting Life’s bluesy tribute to skepticism, and “Bess You Is My Woman Now,” Porgy’s heartfelt promise to protect his beloved. Other featured tunes include “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing,” “I Got Plenty of Nuttin’,” “Picnic Parade,” and the opera’s weary but hopeful finale, “O Lawd I’m On My Way.”

As Gershwin’s longtime Broadway associate, Bennett respected the composer’s preferences whenever he could, creating as authentic a “Symphonic Picture” as possible, right down to the sprightly banjo in “I Got Plenty of Nuttin’.”

—René Spencer Saller

About the Artists

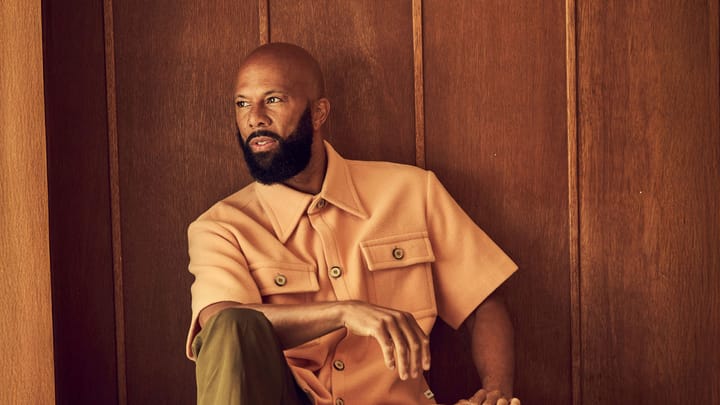

Thomas Wilkins

Thomas Wilkins is principal conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, artistic advisor for education and community engagement at the Boston Symphony, principal guest conductor of the Virginia Symphony, and the Henry A. Upper Chair of orchestral conducting at Indiana University. He served as music director of the Omaha Symphony until 2021, and other past positions have included resident conductor of the Detroit Symphony and Florida Orchestra and associate conductor of the Richmond Symphony in Virginia. He also has served on the music faculties of North Park University in Chicago, the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga, and Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. He has guest conducted orchestras throughout the United States and made his San Francisco Symphony debut in December 2019.

Devoted to promoting a lifelong enthusiasm for music, Wilkins brings energy and commitment to audiences of all ages. He has received many awards, including the League of American Orchestras’ Gold Baton Award and the Omaha Entertainment and Arts Awards Lifetime Achievement Award for Music. Boston’s Longy School of Music awarded him the Leonard Bernstein Lifetime Achievement Award for the Elevation of Music in Society, and he was the beneficiary of an honorary doctorate of the arts from the Boston Conservatory.

Michelle Cann

Michelle Cann has appeared with the Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony, and the São Paulo Municipal Symphony. Her honors include the Sphinx Medal of Excellence and the Andrew Wolf Chamber Music Award. In 2024 she was named the inaugural Christel DeHaan Artistic Partner of the American Pianists Association. She makes her San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

A leading interpreter of Florence Price, Cann recorded Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement with the New York Youth Symphony, which won a Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance. Her solo debut album, Revival, featuring music by Price and Margaret Bonds, was released in May 2023 on the Curtis Studio label. With soprano Karen Slack, she recorded Beyond the Years, featuring 19 unpublished songs by Price.

Cann holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Cleveland Institute of Music and an artist’s diploma from the Curtis Institute of Music. She joined the Curtis piano faculty in 2020 as the inaugural Eleanor Sokoloff Chair in Piano Studies and is also on the piano faculty of the Manhattan School of Music.